Wilhelm Backhaus Plays Chopin, Liszt, Schumann & Encore Pieces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Universi^ Aaicronlms Intemationêd

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

110766 Bk Backhaus EU 17/06/2004 11:23Am Page 4

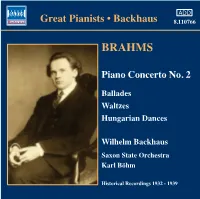

110766 bk Backhaus EU 17/06/2004 11:23am Page 4 Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Waltzes, Op. 39 ADD Piano Concerto No. 2 in B flat major, Op. 83 7 No. 1 in B major 0:50 Great Pianists • Backhaus 8.110766 8 No. 2 in E major 1:12 1 Allegro non troppo 16:04 9 No. 3 in G sharp minor 0:43 2 Allegro appassionato 8:05 0 No. 4 in E minor 0:30 3 Andante 11:53 ! No. 5 in E major 1:01 4 Allegretto grazioso 9:06 @ No. 6 in C sharp major 0:53 # No. 7 in C sharp minor 1:10 Saxon State Orchestra • Karl Böhm $ No. 8 in B flat major 0:35 BRAHMS % No. 9 in D minor 0:50 Recorded June, 1939 in Dresden ^ No. 10 in G major 0:29 Matrices: 2RA 3956-2, 3957-1, 3958-1, 3959-3A, & No. 11 in B minor 0:39 3960-1, 3961-1A, 3962-1, 3963-3, 3964-3A, * No. 12 in E major 0:49 3965-2, 3966-2 and 3967-1 ( No. 13 in B major 0:26 First issued on HMV DB 3930 through 3935 ) No. 14 in G sharp minor 0:36 Piano Concerto No. 2 ¡ No. 15 in A flat major 1:18 Ballades, Op. 10 ™ No. 16 in C sharp minor 1:10 5 No. 1 in D minor (“Edward”) 4:07 Recorded 27th January, 1936 6 No. 2 in D major 4:59 in EMI Abbey Road Studio No. 3 Ballades Matrices: 2EA 3010-5, 3011-5 and 3012-4 Recorded 5th December, 1932 First issued on HMV DB 2803 and 2804 in EMI Abbey Road Studio No. -

MC Ensemble >> Label

approx MC ensemble >> label UK retail Composer & Works Artists barcode MC 142 1CD Christopher Ball: Cello Concerto; Song Without Stjepan Hauser (cello); Yoko Misumi (pno) 851950001421 14.99 Words; Roundelay; Close of the Day; For Stjepan Emerald Concert Orchestra, Folksongs arrangements: Scarborough conducted Christopher Ball Fair; Star of County Down; Brigg Fair; Bonny Dundee/Water is Wide MC 143 1CD Christopher Ball: Horn Concerto; Oboe Concerto Tim Thorpe (horn) Paul Arden-Taylor (Oboe) 851950001438 14.99 In the Yorkshire Dales & Roger Armstrong flute, Leslie Craven clarinet On a Beautiful Day (both Flute/oboe/Clarinet) Emerald Concert Orchestra, Celtic Moods & A Summer Day (both oboe & flute) conducted Christopher Ball Invocations of Pan for solo flute MC 151 1CD Christopher Ball: 'Piper of Dreams' Paul Arden-Taylor (cor anglais, recorder) 5055354471513 14.99 Cor Anglais & Recorder Concertos Leslie Craven (Clarinet) Clarinet Quintet; Scenes from a Comedy [1-3] Emerald Concert Orch Caprice on Baroque Themes [8-10] Adderbury Ensemble Christopher Ball (conductor) MC 152 1CD Beethoven: Piano Sonatas Vol.II (v.1 = mc147) Radoslav Kvapil 5055354471520 7.99 Piano Sonata No.13 (Eb major) Piano Sonata No.14 (C# minor) 'Moonlight' Brand new recordings 2014 Piano Sonata No.23 (F minor) 'Appassionata' Piano Sonata No.25 (G major) Musical Concepts Label Cat no. No. MC = www.musicalconcepts.net Musical Concepts 2014 barcode approx NOV2014 discs Works Artist(s) UK dvds retail MCDV111 1 DVD: Karaoke Opera (popular Tenor arias) various artists 851950001117 -

2015 Programme Bergen International Festival

BERGEN 27 MAY — 10 JUNE 2015 2015 PROGRAMME BERGEN INTERNATIONAL MORE INFO: WWW.FIB.NO FESTIVAL PREFACE BERGEN INTERNATIONAL 003 FESTIVAL 2015 Love Enigmas Love is a perpetually fascinating theme in the Together with our collaborators we aim to world of art. The most enigmatic of our emotions, create a many-splendoured festival – in the it brings us joy when we experience it set to music, truest sense of the word – impacting the lives of AN OPEN INVITATION recounted in literature or staged in the theatre, in our audiences in unique and unmissable ways, dance and in film. We enjoy it because art presents both in venues in the city centre, the composers’ TO VISIT OUR 24-HOUR us with mirror images of ourselves and of the most homes and elsewhere in the region. important driving forces in our lives. OPEN BANK The Bergen International Festival is an event Like a whirling maelstrom love can embrace in which artists from all over the world want ON 5-6 JUNE 2015 us and suck us in and down into the undertow to participate, and they are attracted to the with unforeseeable consequences. Love unites playfulness, creativity and tantalizing energy high and low, selfishness and selflessness, self- of the festival. The Bergen International Festival Experience Bergen International Festival at affirmation and self-denial, and carries us with is synonymous with a high level of energy and our branch at Torgallmenningen 2. There will equal portions of blindness and ruthlessness a zest for life and art. Like an explorer, it is be activities and mini-concerts for children into the embrace of the waterfall, where its unafraid, yet approachable at the same time. -

Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance

Münsteraner Schriften zur zeitgenössischen Musik 5 Ina Rupprecht (ed.) Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance Music in the ›Reichskommissariat Norwegen‹ (1940–45) Münsteraner Schrift en zur zeitgenössischen Musik Edited by Michael Custodis Volume 5 Ina Rupprecht (ed.) Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance Music in the ‘Reichskommissariat Norwegen’ (1940–45) Waxmann 2020 Münster x New York The publication was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft , the Grieg Research Centre and the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster as well as the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Münster. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek Th e Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografi e; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de Münsteraner Schrift en zur zeitgenössischen Musik, Volume 5 Print-ISBN 978-3-8309-4130-9 E-Book-ISBN 978-3-8309-9130-4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.31244/9783830991304 CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 Waxmann Verlag GmbH, 2020 Steinfurter Straße 555, 48159 Münster www.waxmann.com [email protected] Cover design: Pleßmann Design, Ascheberg Cover pictures: © Hjemmefrontarkivet, HA HHI DK DECA_0001_44, saddle of sources regarding the Norwegian resistance; Riksarkivet, Oslo, RA/RAFA-3309/U 39A/ 4/4-7, img 197, Atlantic Presse- bilderdienst 12. February 1942: Th e newly appointed Norwegian NS prime minister Vidkun Quisling (on the right) and Reichskomissar Josef Terboven (on the left ) walking along the front of an honorary -

Cordelia Williams Piano

SOMMCD 0150 ROBERT SCHUMANN (1810-1856) DDD Davidsbündlertänze, Op. 6 Fantasie in C major, Op. 17 Theme with Variations in E flat major, WoO 24 (‘Geistervariationen’) COrdELIA WILLIAms piano Davidsbündlertänze, Op. 6 (15:16) Davidsbündlertänze, Op. 6 (19:30) Fantasie in C, Op. 17 (31:53) (Book I) (Book II) bu Durchaus phantastisch und 1 Lebhaft 1:34 bl Balladenmäßig. Sehr rasch 1:34 leidenschaftlich vorzutragen 13:30 cl 2 Innig 1:30 bm Einfach 1:08 Mäßig 7:45 cm 3 Mit Humor 1:23 bn Mit Humor 0:45 Langsam getragen 10:38 4 Ungeduldig 0:56 bo Wild und lustig 3:34 Geistervariationen (10:26) 5 Einfach 1:50 bp Zart und singend 2:35 cn Theme – Leise, innig 1:52 6 Sehr rasch 1:54 bq Frisch 2:00 co Var. I 1:17 CORDELIA 7 Nicht schnell 3:57 br Mit gutem Humor 1:42 cp Var .II – Canonisch 1:37 WILLIAMS 8 Frisch 0:41 bs Wie aus der Ferne 3:49 cq Var. III – Etwas belebter 1:41 9 Lebhaft 1:28 bt Nicht schnell 2:19 cr Var .IV 1:56 cs Var. V 2:00 SCHUMANN NEW HORIZONS Total duration: 77:06 Davidsbündlertänze Fantasie Recording location: Turner Sims Concert Hall, University of Southampton on 10 & 11 January 2015 Steinway Concert Grand, Model 'D' NEW HORIZONS Geistervariationen Recording Engineer/Producer: Paul Arden-Taylor Executive Producer: Siva Oke Front Cover Photo: Bella West Design: Andrew Giles piano © & 2015 SOMM RECORDINGS · THAMES DITTON · SURREY · ENGLAND Made in the EU Among those manuscripts were five unknown symphonies and the three late ROBERT SCHUMANN piano sonatas, and it was in those sonatas that Schubert had achieved his unique Davidsbündlertänze, Op. -

USHMM Finding

http://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection MARIAN FILAR [1-1-1] THIS IS AN INTERVIEW WITH: MF - Marian Filar [interviewee] EM - Edith Millman [interviewer] Interview Dates: September 5, and November 16, 1994, June 16, 1995 Tape one, side one: EM: This is Edith Millman interviewing Professor Marian Filar. Today is Septem- ber 5, 1994. We are interviewing in Philadelphia. Professor Filar, would you tell me where you were born and when, and a little bit about your family? MF: Well, I was born in Warsaw, Poland, before the Second World War. My father was a businessman. He actually wanted to be a lawyer, and he made the exam on the university, but he wasn’t accepted, but he did get an A, but he wasn’t accepted. EM: Could you tell me how large your family was? MF: You mean my general, just my immediate family? EM: Yeah, your immediate family. How many siblings? MF: We were seven children. I was the youngest. I had four brothers and two sis- ters. Most of them played an instrument. My oldest brother played a violin, the next to him played the piano. My sister Helen was my first piano teacher. My sister Lucy also played the piano. My brother Yaacov played a violin. So there was a lot of music there. EM: I just want to interject that Professor Filar is a known pianist. Mr.... MF: Concert pianist. EM: Concert pianist. Professor Filar, could you tell me what your life was like in Warsaw before the war? MF: Well, it was fine. -

Inventive and Virtuosic CARNAVAL, Op. 9, Was Written by Robert Schumann in 1834 and Published in 1835

Inventive and virtuosic CARNAVAL, Op. 9, was written by Robert Schumann in 1834 and published in 1835. It originated from his unfinished variations on a Trauerwalzer (Sehnsucht) by Franz Schubert, and dedicated to the violinist Karol Lipiński. Subtitled Scènes mignonnes sur quatre notes--Little Scenes on Four Notes--this composition is a series of musical vignettes, picturing masked personalities at Carnival: Schumann himself (in fictitious Florestan and Eusebius, who embodied his split personality), his friends, contemporaries, and characters from improvised Italian comedy, commedia dell'arte. In 1834 Schumann was secretly engaged, although for only few months, to Ernestine von Fricken - a student of his own teacher and future father-in-law, Frederick Wieck. Schumann symbolically based almost every scene of Carnaval on pitch structure with German names: his fiancée's hometown, Asch: "A" = A natural, "S" (Es) = E flat, "C" = C natural, and "H" = B. In reordering of the letters to S-C-H-A composer saw his own name = "SCHumAnn". In addition, A-S-C-H is a part of the German word Fasching (carnival). From 22 sections of this piece Schumann did not number Sphinxes and Intermezzo:Paganini. 1. Préambule (Quasi maestoso; Ab Major) The opening Préambule contains a section from the Variations on a Theme of Schubert (Trauerwalzer, Op. 9/2, (D. 365). It is not structured around A-S-C-H pattern. 2. Pierrot (Moderato; Eb Major;) Pierrot is a character from the Commedia dell'arte. 3. Arlequin (Bb; Vivo) Harlequin is another character from the Commedia dell'arte. 4. Valse noble (Un poco maestoso; Bb Major;) 5. -

View, Folk Music and Poetry Should Be Valued for Their Spontaneity and Close Relation to the Expression of Real Life

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ THE IMPACT OF THE LIED ON SELECTED PIANO WORKS OF FRANZ SCHUBERT, ROBERT SCHUMANN, AND JOHANNES BRAHMS A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS IN PIANO PERFORMANCE of the College-Conservatory of Music 2004 by Yueh-Reng Lin B.M., National Taiwan Normal University, 1994 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 1998 Committee Chair: Professor Karin Pendle ABSTRACT In the nineteenth-century, the German lied, with its subtle expression of poetry and its intimate lyricism, revealed individual expression and emotional content. The piano music in this era also raised a new approach to pianism and the aesthetic of German Romanticism. Composed by three masters in both genres, selected piano works including Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasia Op.15, Schumann’s Fantasie Op.17, and Waldszenen, Op.82, and Brahms’s Sonata Op.5 in F Minor, demonstrate their innermost poetic quality, evident in their unique musical language, which is derived profoundly from the spirit of the lied. To explore the link between lied and piano music, the compositional background, and the thematic, harmonic and structural schemes of these works are analyzed in detail, along with the ways which vocal music had an impact on the style of these piano works. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis has been done passionately, as insomuch as painfully. -

EILEEN JOYCE the Complete Parlophone & Columbia Solo Recordings 1933–1945

EILEEN JOYCE The complete Parlophone & Columbia solo recordings 1933–1945 THE MATTHAY PUPILS 2 EILEEN JOYCE The complete Parlophone & Columbia solo recordings 1933–1945 3 1 The Parlophone 78s (78.28) JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685–1750) 1. Fantasia and Fugue in A minor BWV944 E11354 (matrices CXE 8936/7), recorded on 7 February 1938 (5.27) NB: This title has been misattributed as BWV894 in all previous reissues DOMENICO PARADIES (1707–1791) 2. Toccata in A major from Sonata No 6 E11354 (matrix CXE 8937), recorded on 7 February 1938 (2.36) WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756–1791) 3. Rondo in A major K386 (orchestra/Clarence Raybould) E11292 (matrices CXE 7450/1), (7.29) recorded on 2 February 1936 Suite K399 excerpts 4. Allemande E11443 (matrix CXE 9813), recorded on 26 May 1939 (1.54) 5. Courante (2.18) Sonata in C major K545 (13.03) 6. Allegro E11442/3 (matrices CXE 10382/4), recorded on 26 May 1940 (4.34) 7. Andante (6.46) 8. Rondo (1.43) FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797–1828) 9. Andante in A major D604 E11403 (matrix CXE9619), recorded on 7 February 1939 (4.58) 10. Impromptu in E flat major D899 No 2 E11403 (matrix CXE9620), recorded on 7 February 1939 (4.09) 11. Impromptu in A flat major D899 No 4 E11440 (matrices CXE 10217/8), recorded on 18 December 1939 (7.34) FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN (1810–1849) 12. Nocturne in E flat major Op 9 No 2 E11448 (matrix CXE 10467), recorded on 3 May 1940 (4.42) 13. Nocturne in B major Op 32 No 1 E11448 (matrix CXE 10466), recorded on 3 May 1940 (4.30) 14. -

F a N T a S I E S S Tanislav Khristen K O P I a N O

F a n t a s i e s s tanislav Khristen K o p i a n o s C h UM a n n B r UCK n e r Z e M l i n s K Y B r a h M s F a n t a s i e s s tanislav Khristen K o RobeRt Schumann (1810 –1856) Fantasie in C major, op.17 1 I. Durchaus phantastisch und leidenschaftlich vorzutragen 13:10 2 II. Massig. Durchaus energisch 7:26 3 III. Langsam getragen. Durchweg leise zu halten 10:37 anton BruckneR (1824 –1896) 4 Fantasie in G major 3:29 alexandeR ZemlinSky (1871–1942) Fantasien über Gedichte von richard Dehmel, op. 9 5 I. Stimme des Abends 3:11 6 II. Waldseligkeit 3:42 7 III. Liebe 3:44 8 IV. Käferlied 1:29 JohanneS BrahmS (1833 –1897) Fantasien, op. 116 9 I. Capriccio in D minor 2:37 10 II. Intermezzo in A minor 4:45 11 III. Capriccio in G minor 4:04 12 IV. Intermezzo In E major 5:42 13 V. Intermezzo in E minor 4:05 14 VI. Intermezzo in E major 3:34 15 VII. Capriccio in D minor 2:44 Playing Time: 74:20 3 r e a l i Z i n G t h e F a n ta s t i C a l ‘FAntASIA’ IS An InStruMEntAL ForM—with roots reaching back to the renaissance—whose invention and flexible structure are fashioned by the composer’s own fantasy and imagination. Here pianist Stanislav Khristenko serves as dream interpreter to the fantasies of Brahms, Bruckner, Schumann and Zemlinsky. -

Clara, Clarified by Brian Lauritzen

About the Program Clara, Clarified By Brian Lauritzen It’s impossible to properly talk about While separated, he would send 25 years before that Beethoven statue the music of Robert Schumann without letters (often times also enclosing was unveiled in Bonn, the 50-year-old recognizing the incalculable music he had written) to Clara composer was coming off the biggest contributions Clara Wieck (later expressing his love in words and thing he had ever written for the Schumann) made to Robert’s output, music. The first movement of the piano and getting ready to compose psyche and creative voice. At a time Fantasie, Schumann said, “may well the biggest thing he would ever write when women were discouraged (and be the most passionate I have ever for orchestra. The Piano Sonata No. even hindered) from composing, Clara composed—a deep lament for you.” 30 in E Major, Op. 109, comes just composed. At a time when female after the monumental Hammerklavier instrumental soloists were rare, and Clara likely would have understood Sonata and a couple of years before their success even more so, Clara what Robert was saying with his music the Ninth Symphony. It’s much thrived. At a time when many male even if he hadn’t included the verbal smaller in scale, less dramatic, but artists viewed women as little more explanation. incredibly intimate and personal. He than muses to use and discard once described it as “a small new piece,” “inspiration” left, Clara was a confidante, At the end of the opening movement, and dedicated it to Maximiliane coach and even a mentor.