A Performer's Guide to Interpretive Issues In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mozart Magic Philharmoniker

THE T A R S Mass, in C minor, K 427 (Grosse Messe) Barbara Hendricks, Janet Perry, sopranos; Peter Schreier, tenor; Benjamin Luxon, bass; David Bell, organ; Wiener Singverein; Herbert von Karajan, conductor; Berliner Mozart magic Philharmoniker. Mass, in C major, K 317 (Kronungsmesse) (Coronation) Edith Mathis, soprano; Norma Procter, contralto...[et al.]; Rafael Kubelik, Bernhard Klee, conductors; Symphonie-Orchester des on CD Bayerischen Rundfunks. Vocal: Opera Così fan tutte. Complete Montserrat Caballé, Ileana Cotrubas, so- DALENA LE ROUX pranos; Janet Baker, mezzo-soprano; Nicolai Librarian, Central Reference Vocal: Vespers Vesparae solennes de confessore, K 339 Gedda, tenor; Wladimiro Ganzarolli, baritone; Kiri te Kanawa, soprano; Elizabeth Bainbridge, Richard van Allan, bass; Sir Colin Davis, con- or a composer whose life was as contralto; Ryland Davies, tenor; Gwynne ductor; Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal pathetically brief as Mozart’s, it is Howell, bass; Sir Colin Davis, conductor; Opera House, Covent Garden. astonishing what a colossal legacy F London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. Idomeneo, K 366. Complete of musical art he has produced in a fever Anthony Rolfe Johnson, tenor; Anne of unremitting work. So much music was Sofie von Otter, contralto; Sylvia McNair, crowded into his young life that, dead at just Vocal: Masses/requiem Requiem mass, K 626 soprano...[et al.]; Monteverdi Choir; John less than thirty-six, he has bequeathed an Barbara Bonney, soprano; Anne Sofie von Eliot Gardiner, conductor; English Baroque eternal legacy, the full wealth of which the Otter, contralto; Hans Peter Blochwitz, tenor; soloists. world has yet to assess. Willard White, bass; Monteverdi Choir; John Le nozze di Figaro (The marriage of Figaro). -

March 21, 2018: to Pledge, Please Click Here!

March 21, 2018: (Full-page version) Close Window Spring Pledge Drive Continues! To Pledge, Please Click Here! Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, 00:01 Buy Now! Mozart Fantasia in C minor, K. 475 Mitsuko Uchida Philips 412 617 028941261724 Awake! Huggett/Bury/Amsterdam 00:15 Buy Now! Bach Concerto in D minor for 2 Violins, BWV 1043 Erato 75358 08908853582 Baroque/Koopman 00:32 Buy Now! Haydn Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Harrell/Academy SMF/Marriner EMI 69009 077776900926 01:00 Buy Now! Elgar Serenade for Strings in E minor, Op. 20 English String Orch./Boughton Nimbus 5008 n/a USSR Radio and TV 01:12 Buy Now! Mussorgsky Night on Bald Mountain Melodiya 860 015775186026 Orchestra/Fedoseyev 01:25 Buy Now! Bellini Night Shadow London Festival Ballet/Kern Seraphim 69089 724356908925 02:01 Buy Now! Tchaikovsky Capriccio italien, Op. 45 Cincinnati Symphony/Kunzel Telarc 80041 N/A 02:17 Buy Now! Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 6 in F, Op. 10 No. 2 Wilhelm Kempff DG 429 306 n/a 02:31 Buy Now! Brahms String Quintet No. 1 in F, Op. 88 Steinhardt/Shanghai Quartet Delos 3198 013491319827 03:01 Buy Now! Rossini Overture ~ Semiramide Buffalo Philharmonic/Falletta Beau Fleuve n/a 692863162324 03:15 Buy Now! Mozart Violin Concerto No. 4 in D, K. 218 Grumiaux/London Symphony/Davis Philips 416 632 028941663221 BMG 03:39 Buy Now! Shostakovich Incidental Music to "Hamlet" Boston Pops/Fiedler 63308 090266330829 Entertainment 04:00 Buy Now! Strauss, R. Symphony in D minor Hong Kong Philharmonic/Schermerhorn Marco Polo 8.220323 73009923232 04:37 Buy Now! Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. -

Benjamin Grosvenor, Piano

BENJAMIN GROSVENOR, PIANO a formidable technician and a thoughtful, coolly assured interpreter - Allan Kozinn, New York Times, ...a skill and talent not heard since Kissins teenage Russian debut - Bryce Morrison, Gramophone Magazine British pianist Benjamin Grosvenor is internationally recognized for his electrifying performances and penetrating interpretations. An exquisite technique and ingenious flair for tonal colour are the hallmarks which make Benjamin Grosvenor one of the most sought-after young pianists in the world. His virtuosic command over the most strenuous technical complexities never compromises the formidable depth and intelligence of his interpretations. Described by some as a Golden Age pianist (American Record Guide) and one almost from another age (The Times), Benjamin is renowned for his distinctive sound, described as poetic and gently ironic, brilliant yet clear-minded, intelligent but not without humour, all translated through a beautifully clear and singing touch (The Independent). Benjamin first came to prominence as the outstanding winner of the Keyboard Final of the 2004 BBC Young Musician Competition at the age of eleven. Since then, he has become an internationally regarded pianist performing with orchestras including the London Philharmonic, RAI Torino, New York Philharmonic, Philharmonia, Tokyo Symphony, and in venues such as the Royal Festival Hall, Barbican Centre, Singapores Victoria Hall, The Frick Collection and Carnegie Hall (at the age of thirteen). Benjamin has worked with numerous esteemed conductors including Vladimir Ashkenazy, Jií Blohlávek, Semyon Bychkov and Vladimir Jurowski. At just nineteen, Benjamin performed with the BBC Symphony Orchestra on the First Night of the 2011 BBC Proms to a sold-out Royal Albert Hall. -

Complete Beethoven Piano Sonatas--Artur Schnabel (1932-1935) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by James Irsay (Guest Post)*

The Complete Beethoven Piano Sonatas--Artur Schnabel (1932-1935) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by James Irsay (guest post)* Artur Schnabel Austrian pianist Artur Schnabel has been called “the man who invented Beethoven”... a strange thing to say considering Schnabel was born more than half a century after Beethoven, universally recognized as the greatest composer in Europe, died in 1827. What, then, did Artur Schnabel invent? The 32 piano sonatas of Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) represent one of the great artistic achievements in human history, and stand as the musical autobiography of the great composer's maturity, from his 25th until his 53rd year, four years before his death. The fruit of those years mark a staggering creative journey that began and ended in the composer's adopted home of Vienna, “Music Central” to the German-speaking world. Beethoven's musical path led from the domain of Haydn and Mozart to the world of his late period, when the agonizing progress of his deafness had become complete. By then, Beethoven's musical narrative had begun to speak a new language, proceeding according to a new logic that left many listeners behind. While the beauties of his music and his deep genius were generally recognized, at the same time, it was thought by some critics that Beethoven frequently smudged things up with his overly- bold, unfettered invention, even well before his final period: Beethoven, who is often bizarre and baroque, takes at times the majestic flight of an eagle, and then creeps in rocky pathways. He first fills the soul with sweet melancholy, and then shatters it by a mass of shattered chords. -

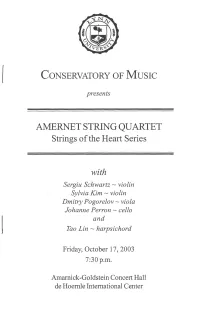

2003-2004 Amernet String Quartet: Strings of the Heart Series

I CONSERVATORY OF Music presents Al\1ERNET STRING QUARTET Strings of the Heart Series with Sergiu Schwartz ~ violin Sylvia Kim~ violin Dmitry Pogorelov ~viola Johanne Perron ~ cello and Tao Lin ~ harpsichord Friday, October 17, 2003 7:30p.m. Amamick-Goldstein Concert Hall de Hoemle International Center Program String Quartet No. 19 in C Major, K 465 "Dissonance" ..... W. A. Mozart (1756-1791) Adagio-Allegro Andante Cantabile Menuetto-Allegro Allegro Amernet String Quartet Misha Vitenson - violin Marsha Littley- violin Michael Klotz- viola Javier Arias- cello Concerto ind minor for Two Violins, BWV 1043 .............. J. S. Bach (1685-1750) Vivace Largo ma non tanto Allegro Sergiu Schwartz-violin Misha Vitenson - violin Marcia Littley, Sylvia Kim-violin Michael Klotz, Dmitry Pogorelov -viola Javier Arias, Johanne Perron-cello Tao Lin - harpsichord INTERMISSION 1 Octet, Op. 20 .................................................................... Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) Allegro moderato Andante Scherzo -Allegro leggierissimo Presto Misha Vitenson, Sergiu Schwartz, Sylvia Kim, MarciaLittley-violin Michael Klotz, Dmitry Pogorelov -viola Javier Arias, Johanne Perron-cello Biographies r Amernet String Quartet The Amernet String Quartet, Ensemble-in-Residence at Northern .,_ Kentucky University, has garnered worldwide praise and recognition as one of today's exceptional young string quartets. i It rose to international attention after only one year of existence, after winning the Gold Medal at the 7th Tokyo International Music Competition in 1992. Three years later the group was the First Prize winner of the prestigious 5th Banff International String Quartet Competition. The Amernet String Quartet has been described by The New York Times as "an accomplished and intelligent ensemble," and by the Niirnberger Nachrichten (Germany) as "fascinating with flawless intonation, extraordinary beauty of sound, virtuosic brilliance and homogeneity of ensemble." The Amernet String Quartet formed in 1991, while two of its members were students at The Juilliard School. -

October 2015

October 2015 Bertrand Chamayou INSIDE: Ian Bostridge | Sarah Connolly Ehnes Quartet | Thomas Hampson Alina Ibragimova & Cédric Tiberghien Magdalena Kozˇená & Mitsuko Uchida Steven Isserlis | Robert Levin Sandrine Piau | Christoph Prégardien Stile Antico | Vox Luminis And many more Box Office 020 7935 2141 Online Booking www.wigmore-hall.org.uk How to Book Wigmore Hall Box Office 36 Wigmore Street, London W1U 2BP In Person 7 days a week: 10 am – 8.30 pm. Days without an evening concert 10 am – 5 pm. No advance booking in the half hour prior to a concert. Please note that the Box Office with be closed for bookings in person from Monday 27 July to Friday 4 September. By Telephone: 020 7935 2141 7 days a week: 10 am – 7 pm. Days without an evening concert 10 am – 5 pm. There is a non-refundable £3.00 administration fee for each transaction, which includes the return of your tickets by post if time permits. Online: www.wigmore-hall.org.uk 7 days a week; 24 hours a day. There is a non-refundable £2.00 administration charge. Standby Tickets Standby tickets for students, senior citizens and the unemployed are available from one hour before the performance (subject to availability) with best available seats sold at the lowest price. NB standby tickets are not available for Lunchtime and Coffee Concerts. Group Discounts Discounts of 10% are available for groups of 12 or more, subject to availability. Latecomers Latecomers will only be admitted during a suitable pause in the performance. Facilities for Disabled People full details available from 020 7935 2141 or [email protected] Wigmore Hall has been awarded the Bronze Charter Mark from Attitude is Everything TICKETS Unless otherwise stated, tickets are A–D divided into five prices ranges: BALCONY Stalls C – M W–Y Highest price T–V Stalls A – B, N – P Q–S 2nd highest price Balcony A – D N–P 2nd highest price STALLS Stalls BB, CC, Q – S C–M 3rd highest price A–B Stalls AA, T – V CC CC 4th highest price BB BB PLATFORM Stalls W – Y AAAA AAAA Lowest price This brochure is available in alternative formats. -

Rachmaninoff's Rhapsody on a Theme By

RACHMANINOFF’S RHAPSODY ON A THEME BY PAGANINI, OP. 43: ANALYSIS AND DISCOURSE Heejung Kang, B.A., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2004 APPROVED: Pamela Mia Paul, Major Professor and Program Coordinator Stephen Slottow, Minor Professor Josef Banowetz, Committee Member Steven Harlos, Interim Chair of Piano Jessie Eschbach, Chair of Keyboard Studies James Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrill, Interim Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Kang, Heejung, Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, Op.43: Analysis and Discourse. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2004, 169 pp., 40 examples, 5 figures, bibliography, 39 titles. This dissertation on Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, Op.43 is divided into four parts: 1) historical background and the state of the sources, 2) analysis, 3) semantic issues related to analysis (discourse), and 4) performance and analysis. The analytical study, which constitutes the main body of this research, demonstrates how Rachmaninoff organically produces the variations in relation to the theme, designs the large-scale tonal and formal organization, and unifies the theme and variations as a whole. The selected analytical approach is linear in orientation - that is, Schenkerian. In the course of the analysis, close attention is paid to motivic detail; the analytical chapter carefully examines how the tonal structure and motivic elements in the theme are transformed, repeated, concealed, and expanded throughout the variations. As documented by a study of the manuscripts, the analysis also facilitates insight into the genesis and structure of the Rhapsody. -

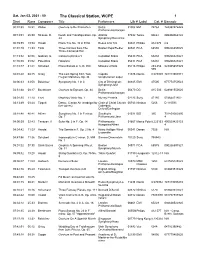

Sat, Jan 02, 2021 - 00 the Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Sat, Jan 02, 2021 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 10:31 Weber Overture to Der Freischutz Berlin 01006 EMI 74764 724357476423 Philharmonic/Karajan 00:13:0125:39 Strauss, R. Death and Transfiguration, Op. Atlanta 07032 Telarc 80661 089408066122 24 Symphony/Runnicles 00:39:55 19:54 Haydn Piano Trio No. 36 in E flat Beaux Arts Trio 04027 Philips 432 070 n/a 01:01:1911:33 Falla Three Dances from The Boston Pops/Fiedler 04581 RCA 68550 090266855025 Three-Cornered Hat 01:13:5202:08 Gabrieli, G. Canzona prima a 5 Canadian Brass 05433 RCA 63238 090266323821 01:16:00 01:02 Palestrina Hosanna Canadian Brass 05433 RCA 63238 090266323821 01:18:1741:41 Schubert Piano Sonata in A, D. 959 Mitsuko Uchida 05116 Philips 289 456 028945657929 579 02:01:2804:15 Grieg The Last Spring from Two Capella 11036 Naxos 8.578009 747313800971 Elegiac Melodies, Op. 34 Istropolitana/Leaper 02:06:4343:50 Balakirev Symphony No. 1 in C City of Birmingham 00845 EMI 47505 077774750523 Symphony/Jarvi 02:51:4808:17 Beethoven Overture to Egmont, Op. 84 Berlin 00470 DG 415 506 028941550620 Philharmonic/Karajan 03:01:3511:14 Liszt Mephisto Waltz No. 1 Murray Perahia 02233 Sony 47180 07464471802 03:13:4903:44 Tippett Dance, Clarion Air (madrigal for Choir of Christ Church 00783 Nimbus 5266 D 110593 five voices) Cathedral, Oxford/Darlington 03:18:4840:41 Alfven Symphony No. 1 In F minor, Stockholm 01531 BIS 395 731859000395 Op. 7 Philharmonic/Jarvi 4 04:00:5932:43 Taneyev, A. -

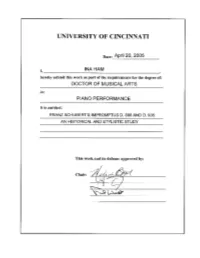

Franz Schubert's Impromptus D. 899 and D. 935: An

FRANZ SCHUBERT’S IMPROMPTUS D. 899 AND D. 935: AN HISTORICAL AND STYLISTIC STUDY A doctoral document submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Keyboard Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2005 by Ina Ham M.M., Cleveland Institute of Music, 1999 M.M., Seoul National University, 1996 B.M., Seoul National University, 1994 Committee Chair: Dr. Melinda Boyd ABSTRACT The impromptu is one of the new genres that was conceived in the early nineteenth century. Schubert’s two sets of impromptus D. 899 and D. 935 are among the most important examples to define this new genre and to represent the composer’s piano writing style. Although his two sets of four impromptus have been favored in concerts by both the pianists and the audience, there has been a lack of comprehensive study of them as continuous sets. Since the tonal interdependence between the impromptus of each set suggests their cyclic aspects, Schubert’s impromptus need to be considered and be performed as continuous sets. The purpose of this document is to provide useful resources and performance guidelines to Schubert’s two sets of impromptus D. 899 and D. 935 by examining their historical and stylistic features. The document is organized into three chapters. The first chapter traces a brief history of the impromptu as a genre of piano music, including the impromptus by Jan Hugo Voŕišek as the first pieces in this genre. -

L'importanza Dell'etica Nella Grande Interpretazione Musicale: Testimonianze E Incontri Con Celebri Pianisti

L’importanza dell’etica nella grande interpretazione musicale: testimonianze e incontri con celebri pianisti Kazimierz Morski Pianista. Direttore d’orchestra. Catedratico di Scienze Musicali Università Slesiana di Katowice Università Autonoma di Madrid1 Università di Roma 2 “Tor Vergata”2 Sintesi. Il saggio è frutto di personali esperienze e di considerazioni sorte nell’accostarsi a grandi personaggi della musica, in questo caso pianistica, il cui impegno etico-estetico sta alla base della profonda grandezza di esecuzioni divenute ormai patrimonio storico. Modelli in tal senso sono stati Neuhaus, Benedetti Michelangeli o Arrau per chi, come me, ha potuto incontrarli o sentirli in concerto e si trova oggi a porli nella prospettiva storica assieme ad altri artisti del mondo compositivo ed interpretativo. Nonostante le differenze e le soggettive concezioni di approccio alla musica, dal concertismo puro, all’impegno didattico, alla riflessione teorica, quanto appare nelle loro realizzazioni è un atteggiamento umano e culturale spesso celato da un nobile riserbo, segno irripetibile dell’arte nella sua essenza. Di qui l’affermazione della necessaria componente etica nell’ambito estetico delle grandi interpretazioni, sia in relazione all’originaria idea creativa che al suo mutare a seconda del gusto e delle epoche. Le testimonianze addotte conducono a profonde considerazioni sul rapporto tra l’elemento ontologico relativo soprattutto alla creatività e quello fenomenologico soggetto alle continue variazioni del modo di sentire. Parole chiave. idea creativa - interpretazione ideale - esecuzione - concertismo - pianisti - personalità artistica - virtuosismo - espressione- tradizione - didattica - etica - estetica - esperienze – testimonianze. Abstract. This essay is the result of personal experiences and considerations while addressing the fate of great musicians – in this case of piano players - whose ethic-aesthetic commitment is behind the greatness of certain interpretations that have become part our cultural heritage. -

2017-2018 Master Class-Leon Fleisher

Welcome to the 2017-2018 season. The talented students and extraordinary faculty of the Lynn LEON FLEISHER MASTER CLASS Conservatory of Music take this opportunity to share with you the beautiful world of music. Your Wednesday, January 24, 2018 at 7:00 pm ongoing support ensures our place among the premier conservatories Amarnick-Goldstein Concert Hall of the world and a staple of our community. - Jon Robertson, dean PROGRAM There are a number of ways by which you can help us fulfill our mission: Friends of the Conservatory of Music Sonata Op. 2 No. 2 in A Major Ludwig van Beethoven Lynn University’s Friends of the Conservatory of Music is a IV Rondo: Grazioso (1770-1827) volunteer organization that supports high-quality music education through fundraising and community outreach. Raising more than $2 million since 2003, the Friends support Lynn’s effort to provide Chance Israel, piano free tuition scholarships and room and board to all Conservatory of Music students. The group also raises money for the Dean’s Discretionary Fund, which supports the immediate needs of the university’s music performance students. This is accomplished through annual gifts and special events, such as outreach concerts and the annual Gingerbread Holiday Concert. To learn more about joining the Friends and its many benefits, Scherzo No. 4 in E Major Frederic Chopin such as complimentary concert admission, visit Give.lynn.edu/support-music. (1810-1849) The Leadership Society of Lynn University Meiyu Wu, piano The Leadership Society is the premier annual giving society for donors who are committed to ensuring a standard of excellence at Lynn for all students. -

Leonard Bernstein's Piano Music: a Comparative Study of Selected Works

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2018 Leonard Bernstein's Piano Music: A Comparative Study of Selected Works Leann Osterkamp The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2572 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] LEONARD BERNSTEIN’S PIANO MUSIC: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF SELECTED WORKS by LEANN OSTERKAMP A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts, The City University of New York 2018 ©2018 LEANN OSTERKAMP All Rights Reserved ii Leonard Bernstein’s Piano Music: A Comparative Study of Selected Works by Leann Osterkamp This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Date Ursula Oppens Chair of Examining Committee Date Norman Carey Executive Director Supervisory Committee Dr. Jeffrey Taylor, Advisor Dr. Philip Lambert, First Reader Michael Barrett, Second Reader THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Leonard Bernstein’s Piano Music: A Comparative Study of Selected Works by Leann Osterkamp Advisor: Dr. Jeffrey Taylor Much of Leonard Bernstein’s piano music is incorporated in his orchestral and theatrical works. The comparison and understanding of how the piano works relate to the orchestral manifestations validates the independence of the piano works, provides new insights into Bernstein’s compositional process, and presents several significant issues of notation and interpretation that can influence the performance practice of both musical versions.