A Case Study of Educational Initiatives in Dantewada Manisha Priyam, Sanjeev Chopra, Om Prakash Chaudhary1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JOURNALS of the RAJYA SABHA (TWO HUNDRED and TWENTY NINTH SESSION) MONDAY, the 5TH AUGUST, 2013 (The Rajya Sabha Met in the Parliament House at 11-00 A.M.) 11-00 A.M

JOURNALS OF THE RAJYA SABHA (TWO HUNDRED AND TWENTY NINTH SESSION) MONDAY, THE 5TH AUGUST, 2013 (The Rajya Sabha met in the Parliament House at 11-00 a.m.) 11-00 a.m. 1. National Anthem National Anthem was played. 11-02 a.m. 2. Oath or Affirmation Shrimati Kanimozhi (Tamil Nadu) made and subscribed affirmation and took her seat in the House. 11-05 a.m. 3. Obituary References The Chairman made references to the passing away of — 1. Shri Gandhi Azad (ex-Member); 2. Shri Madan Bhatia (ex-Member); 3. Shri Kota Punnaiah (ex-Member); 4. Shri Samar Mukherjee (ex-Member); and 5. Shri Khurshed Alam Khan (ex-Member). The House observed silence, all Members standing, as a mark of respect to the memory of the departed. 1 RAJYA SABHA 11-14 a.m. 4. References by the Chair (i) Reference to the Victims of Flash Floods, Cloudburst and landslides in Uttarakhand and floods due to heavy monsoon rains in several parts of the country The Chairman made a reference to the flash floods, landslides and cloudbursts that took place in Uttarakhand, in June, 2013, in which 580 persons lost their lives, 4473 others were reportedly injured and approximately 5526 persons are reportedly missing. A reference was also made to 20 security personnel belonging to the Indian Air Force National Disaster Response Force and ITBP, involved in rescue and relief operations who lost their lives in a MI-17 Helicopter crash on the 25th of June, 2013 and to the loss of lives and destruction of crops, infrastructure and property in several other parts of the country due to heavy monsoon rains. -

“Being Neutral Is Our Biggest Crime”

India “Being Neutral HUMAN RIGHTS is Our Biggest Crime” WATCH Government, Vigilante, and Naxalite Abuses in India’s Chhattisgarh State “Being Neutral is Our Biggest Crime” Government, Vigilante, and Naxalite Abuses in India’s Chhattisgarh State Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-356-0 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org July 2008 1-56432-356-0 “Being Neutral is Our Biggest Crime” Government, Vigilante, and Naxalite Abuses in India’s Chhattisgarh State Maps........................................................................................................................ 1 Glossary/ Abbreviations ..........................................................................................3 I. Summary.............................................................................................................5 Government and Salwa Judum abuses ................................................................7 Abuses by Naxalites..........................................................................................10 Key Recommendations: The need for protection and accountability.................. -

Brief Industrial Profile of Sukama District

1 Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of Sukama District Carried out by MSME -Development Institute, Raipur (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India,) Phone :- 0771- 2427719 /2422312 Fax: 0771 - 2422312 e-mail: [email protected] Web- www.msmediraipur.gov.in 2 Contents S. No. Topic Page No. 1. General Characteristics of the District 4 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 4 1.2 Topography 4 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 4 1.4 Forest 4 1.5 Administrative set up 5 2. District at a glance 5 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Area in the District Sukama 8 3. Industrial Scenario Of Sukama 8 3.1 Industry at a Glance 8 3.2 Year Wise Trend Of Units Registered 8 3.3 Details Of Existing Micro & Small Enterprises & Artisan Units In The 9 District 3.4 Large Scale Industries / Public Sector undertakings 9 3.5 Major Exportable Item 9 3.6 Growth Trend 9 3.7 Vendorisation / Ancillarisation of the Industry 9 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 10 3.8.1 List of the units in Sukama & nearby Area 10 3.8.2 Major Exportable Item 10 3.9 Service Enterprises 10 3.9.1 Potentials areas for service industry 10 3.10 Potential for new MSMEs 10 4. Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprise 10 5. Action Plan for MSME Schemes 11 6. Steps to set up MSMEs 12 3 4 Brief Industrial Profile of Sukama District 1. General Characteristics of the District Sukma district is the newly formed, southernmost district in Chhattisgarh [South Bastar Region], India. -

Sukma, Chhattisgarh)

1 Innovative initiatives undertaken at . Cashless Village Palnar (Dantewada) . Comprehensive Education Development (Sukma, Chhattisgarh) . Early detection and screening of breast cancer (Thrissur) . Farm Pond On Demand (Maharashtra) . Integrated Solid Waste Management and Generation of Power from Waste (Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh) . Rural Solid Waste Management (Tamil Nadu) . Solar Urja Lamps Project (Dungarpur) . Spectrum Harmonization and Carrier Aggregation . The Neem Project (Gujarat) . The WDS Project (Surguja, Chhattisgarh) Executive Summary Cashless Village Palnar (Dantewada) Background/ Initiatives Undertaken • Gram Panchayat Palnar, made first cashless panchayat of the state • All shops enabled with cashless mechanism through Ezetap PoS, Paytm, AEPS etc. • Free Wi-Fi hotspot created at the market place and shopkeepers asked to give 2-5% discounts on digital transactions • “Digital Army” has been created for awareness and promotion – using Digital band, caps and T-shirts to attract localities • Monitoring and communication was done through WhatsApp Groups • Functional high transaction Common Service Centers (CSC) have been established • Entire panchayat has been given training for using cashless transaction techniques • Order were issued by CEO-ZP, Dantewada for cashless payment mode implementation for MNREGS and all Social Security Schemes, amongst multiple efforts taken by district administration • GP Palnar to also facilitate cashless payments to surrounding panchayats Key Achievements/ Impact • Empowerment of village population by building confidence of villagers in digital transactions • Improvement in digital literacy levels of masses • Local festivals like communal marriage, traditional folk dance festivals, inter village sports tournament are gone cashless • 1062 transactions, amounting to Rs. 1.22 lakh, done in cashless ways 3 Innovation Background Palnar is a village located in Kuakonda Tehsil of Dakshin Bastar Dantewada district in Chhattisgarh. -

Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses

Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses www.rsis.edu.sg ISSN 2382-6444 | Volume 10, Issue 9 | September 2018 A JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR POLITICAL VIOLENCE AND TERRORISM RESEARCH (CTR) The Lamitan Bombing and Terrorist Threat in the Philippines Rommel C. Banlaoi Crime-Terror Nexus in Southeast Asia Bilveer Singh India and the Crime-Terrorism Nexus Ramesh Balakrishnan Crime -Terror Nexus in Pakistan Farhan Zahid Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses Volume 9, Issue 4 | April 2017 1 Building a Global Network for Security Editorial Note Terrorist Threat in the Philippines and the Crime-Terror Nexus In light of the recent Lamitan bombing in the detailing the Siege of Marawi. The Lamitan Southern Philippines in July 2018, this issue bombing symbolises the continued ideological highlights the changing terrorist threat in the and physical threat of IS to the Philippines, Philippines. This issue then focuses, on the despite the group’s physical defeat in Marawi crime-terror nexus as a key factor facilitating in 2017. The author contends that the counter- and promoting financial sources for terrorist terrorism bodies can defeat IS only through groups, while observing case studies in accepting the group’s presence and hold in the Southeast Asia (Philippines) and South Asia southern region of the country. (India and Pakistan). The symbiotic Wrelationship and cooperation between terrorist Bilveer Singh broadly observes the nature groups and criminal organisations is critical to of the crime-terror nexus in Southeast Asia, the existence and functioning of the former, and analyses the Abu Sayyaf Group’s (ASG) despite different ideological goals and sources of finance in the Philippines. -

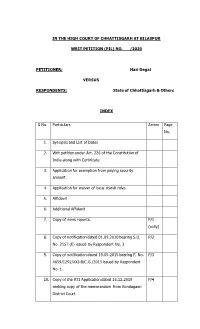

IN the HIGH COURT of CHHATTISGARH at BILASPUR WRIT PETITION (PIL) NO. /2020 PETITIONER: Hari Degal VERSUS RESPONDENTS

IN THE HIGH COURT OF CHHATTISGARH AT BILASPUR WRIT PETITION (PIL) NO. /2020 PETITIONER: Hari Degal VERSUS RESPONDENTS: State of Chhattisgarh & Others INDEX S No. Particulars Annex Page No. 1. Synopsis and List of Dates 2. Writ petition under Art. 226 of the Constitution of India along with Certificate. 3. Application for exemption from paying security amount. 4. Application for waiver of locus standi rules. 5. Affidavit 6. Additional Affidavit 7. Copy of news reports. P/1 (colly) 8. Copy of notification dated 01.09.2010 bearing S.O. P/2 No. 2157 (E) issued by Respondent No. 3 9. Copy of notification dated 19.05.2015 bearing F. No. P/3 4659/1292/XXI-B/C.G./2015 issued by Respondent No. 1. 10. Copy of the RTI Application dated 16.12.2019 P/4 seeking copy of the memorandum from Kondagaon District Court. 11. Copy of notification dated 24.11.2015 bearing S. O. P/5 No. 3161 (E) issued by Respondent No. 3 12. The copy of the judgment The State of Chhattisgarh P/6 and Ors. Vs. National Investigative Agency MANU/CG/0884/2019 13. The copy of the relevant pages of The Fifth Report, P/7 Second Administrative Reforms Commission on ‘Public Order — Justice for Each… Peace for All’ dated 01.06.2007. 14. Vakalatnama BILASPUR SHIKHA PANDEY DATED: 10.01.2020 COUNSEL FOR THE PETITIONER IN THE HIGH COURT OF CHHATTISGARH AT BILASPUR WRIT PETITION (PIL) NO. /2020 PETITIONER: Hari Degal VERSUS RESPONDENTS: State of Chhattisgarh & Others SYNOPSIS The present Petition is filed challenging the legality of the notification dated 19.05.2015 F. -

GIPE-120588.Pdf (2.105Mb)

No. 57 c.s PARLIAMENT OF INDIA RAJYA SABHA CU-. THE CENTRAL INDUSTRIAL SE RITY FORCE BILL, 1968 REPORT OF THE JOINT COMMITTEE (PRESENTED ON THE 12TH FEBRUARY, 1968) RAJYA SABRA SECRETARL-\T NEW DELHI FEBRUARY, 1¢8 CONTENTS---·---- t. Composition of the Joint Committee iii-iv 2. Report of the Joint Committee v-vii 3· Minutes of Dissent viii-xvii 4· Bill as amended by the Joint Committee 1-10 APPBNDJX I-Motion in the Rajya Sabha for reference of the Bill to Joint Committee n-12. APPBNDJX II-M~ti.>n in Lok Sabha APPBNDIX III-Statement of memoranda.'letters received by tho Joint Committee 1'- ·16 APPENDIX IV-List of Organisations/individuat. who tendered evidence before the Joint Committee 17 APPBNDJX V-Minutes of the Sittings of the Joint Committee 18- 46 COMPOSITION OF THE JOINT COMMITTEE ON THE CENTRAL INUDSTRIAL SECURITY FORCE BILL, 1966 MEMBERS Rajya Sabha 1. Shrimati Violet Alva-Chairman. 2. Shri K. S. Ramaswamy 3. Shri M. P. Bhargava "· Shri M. Govinda Reddy 5. Shri Nand Kishore Bhatt 6. Shri Akbar Ali Khan 7. Shri B. K. P. Sinha 8. Shri M. M. Dharia 9. Shri Krishan Kant 10. Shri Bhupesh Gupta 11. Shri K. Sundaram 12. Shri Rajnarain 13. Shri Banka Behary Das 14. Shri D. Thengari 15. Shri A. P. Chatterjee . Lok Sabrnz 16. Shri Vidya Dhar Bajpai 17. Shri D. Balarama Raju 18. Shri Rajendranath Barua 19. Shri Ani! K. Chanda 20. Shri N. C. Chatterjee 21. Shri J. K. Choudhury 22. Shri Ram Dhani Das 23. Shri George Fernandes 24. -

List of Eklavya Model Residential Schools in India (As on 20.11.2020)

List of Eklavya Model Residential Schools in India (as on 20.11.2020) Sl. Year of State District Block/ Taluka Village/ Habitation Name of the School Status No. sanction 1 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Y. Ramavaram P. Yerragonda EMRS Y Ramavaram 1998-99 Functional 2 Andhra Pradesh SPS Nellore Kodavalur Kodavalur EMRS Kodavalur 2003-04 Functional 3 Andhra Pradesh Prakasam Dornala Dornala EMRS Dornala 2010-11 Functional 4 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Gudem Kotha Veedhi Gudem Kotha Veedhi EMRS GK Veedhi 2010-11 Functional 5 Andhra Pradesh Chittoor Buchinaidu Kandriga Kanamanambedu EMRS Kandriga 2014-15 Functional 6 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Maredumilli Maredumilli EMRS Maredumilli 2014-15 Functional 7 Andhra Pradesh SPS Nellore Ozili Ojili EMRS Ozili 2014-15 Functional 8 Andhra Pradesh Srikakulam Meliaputti Meliaputti EMRS Meliaputti 2014-15 Functional 9 Andhra Pradesh Srikakulam Bhamini Bhamini EMRS Bhamini 2014-15 Functional 10 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Munchingi Puttu Munchingiputtu EMRS Munchigaput 2014-15 Functional 11 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Dumbriguda Dumbriguda EMRS Dumbriguda 2014-15 Functional 12 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Makkuva Panasabhadra EMRS Anasabhadra 2014-15 Functional 13 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Kurupam Kurupam EMRS Kurupam 2014-15 Functional 14 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Pachipenta Guruvinaidupeta EMRS Kotikapenta 2014-15 Functional 15 Andhra Pradesh West Godavari Buttayagudem Buttayagudem EMRS Buttayagudem 2018-19 Functional 16 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Chintur Kunduru EMRS Chintoor 2018-19 Functional -

Socio-Economic Survey Report of Villages in Dantewada

SOCIO-ECONOMIC SURVEY & NEEDS ASSESSMENT STUDY IN ESSAR STEEL’S PROJECT VILLAGE Baseline Report of the villages located in three blocks of Dantewada in South Bastar Survey Team of Essar Foundation Deepak David Dr. Tej Prakash Pratik Sethe Socio-economic survey and Need assessment study Kirandul, Dist. Dantewada- Chhattisgarh TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1. ESSAR STEEL INDIA LIMITED, VIZAG OPERATIONS - BENEFICIATION PLANT 1.2. ESSAR FOUNDATION 1.3. PROJECT LOCATION 1.4. OBJECTIVE 1.5. METHODOLOGY 1.6. STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT CHAPTER 2 AREA PROFILE 2.1. DISTRICT PROFILE 2.2. PROFILE OF THE VILLAGES 2.2.1. Location and Layout 2.2.2. Settlement pattern 2.2.3. Population 2.2.4. Sex Ratio 2.2.5. Literacy 2.2.6. Occupation 2.2.7. Education 2.2.8. Health services 2.2.9. Electrification 2.2.10. Road and transportation 2.2.11. Communication facilities CHAPTER 3 FINDING OF THE HOUSEHOLD SURVEY 3.1. BACKGROUND 3.2. METHODOLOGY 3.3. SOCIO- ECONOMIC PROFILES OF THE VILLAGES ESSAR FOUNDATION Page 2 of 86 Socio-economic survey and Need assessment study Kirandul, Dist. Dantewada- Chhattisgarh 3.3.1. # of HH members; Average # of members in HH 3.3.2. Caste/ Tribe and sub-group 3.3.3. Age- Sex Distribution 3.3.4. Marital Status 3.3.5. Literacy Rate 3.3.6. Migration 3.3.7. Occupation pattern 3.3.8. Employment and income 3.3.9. Dependency Ratio 3.3.10. Participation in Public Program 3.3.11. Livestock Population 3.3.12. -

Residential Schools for Children in LWE-Affected Areas of Chhattisgarh

EDUCATION 2.3 Pota Cabins: Residential schools for children in LWE-affected areas of Chhattisgarh Pota Cabins is an innovative educational initiative for building schools with impermanent materials like bamboo and plywood in Chhattisgarh. The initiative has helped reduce the number of out-of-school children and improve enrolment and retention of children since its introduction in 2011. The number of out-of-school children in the 6-14 years age group reduced from 21,816 to 5,780 as the number of Pota Cabins rose from 17 to 43 within a year of the initiative. These residential schools help ensure continuity of education from primary to middle-class levels in Left Wing Extremism affected villages of Dantewada district, by providing children and their families a safe zone where they can continue their education in an environment free of fear and instability. Rationale Secondly, it would also draw children away from the remote and interior areas of villages that are more prone to Left Wing Extremists violence. As these schools are perceived The status of education in Dantewada district of Chhattisgarh as places where children can receive adequate food and was abysmal. As per a 2005 report, the literacy rate of the education, they are often referred to Potacabins locally, as state stood at 30.2% against the state average of 64.7%.1 ‘pota’ means ‘stomach’ in the local Gondi language. The development deficit in the Dakshin Bastar area, which includes Dantewada district, has been largely attributed to the remoteness of villages, lack of proper infrastructure Objectives such as roads and bridges, and weak penetration of communication technology. -

Bastar District Chhattisgarh 2012-13

For official use only Government of India Ministry of Water Resources Central Ground Water Board GROUND WATER BROCHURE OF BASTAR DISTRICT CHHATTISGARH 2012-13 Keshkal Baderajpur Pharasgaon Makri Kondagaon Bakawand Bastar Lohandiguda Tokapal Jagdalpur Bastanar Darbha Regional Director North Central Chhattisgarh Region Reena Apartment, II Floor, NH-43 Pachpedi Naka, Raipur (C.G.) 492001 Ph No. 0771-2413903, 2413689 Email- [email protected] GROUND WATER BROCHURE OF BASTAR DISTRICT DISTRICT AT A GLANCE I Location 1. Location : Located in the SSE part of Chhattisgarh State Latitude : 18°38’04”- 20°11’40” N Longitude : 81°17’35”- 82°14’50” E II General 1. Geographical area : 10577.7 sq.km 2. Villages : 1087 nos 3. Development blocks : 12 nos 4. Population : 1411644 Male : 697359 Female : 714285 5. Average annual rainfall : 1386.77mm 6. Major Physiographic unit : Predominantly Bastar plateau 7. Major Drainage : Indravati , Kotri and Narangi rivers 8. Forest area : 1997.68 sq. km ( Reserved) 390.38 sq. km ( Protected) 2588.75 sq. km (Revenue ) Total – 4976.77 sq.km. III Major Soil 1) Alfisols : Red gravelly, red sandy &red loamy 2) Ultisols : Lateritic,Red & yellow soil IV Principal crops 1) Rice : 2024 ha 2) Wheat : 667ha 3) Maize : 2250 ha V Irrigation 1) Net area sown : 315657 sq. km 2) Net and gross irrigated area : 9592 ha a) By dug wells : 2460 no (758 ha) b By tube wells : 1973 no (2184ha) c) By tank/Ponds : 102 no (1442ha) d) By canals : 15 no ( 421 ha) e) By other sources : 4391 ha VI Monitoring wells (by CGWB) 1) Dug wells -

Statistical Report General Election, 1998 The

STATISTICAL REPORT ON GENERAL ELECTION, 1998 TO THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF MADHYA PRADESH ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NEW DELHI Election Commission of India – State Elections, 1998 Legislative Assembly of Madhya Pradesh STATISCAL REPORT ( National and State Abstracts & Detailed Results) CONTENTS SUBJECT Page No. Part – I 1. List of Participating Political Parties 1 - 2 2. Other Abbreviations And Description 3 3. Highlights 4 4. List of Successful Candidates 5 - 12 5. Performance of Political Parties 13 - 14 6. Candidate Data Summary 15 7. Electors Data Summary 16 8. Women Candidates 17 - 25 9. Constituency Data Summary 26 - 345 10. Detailed Results 346 - 413 Election Commission of India-State Elections, 1998 to the Legislative Assembly of MADHYA PRADESH LIST OF PARTICIPATING POLITICAL PARTIES PARTYTYPE ABBREVIATION PARTY NATIONAL PARTIES 1 . BJP Bharatiya Janata Party 2 . BSP Bahujan Samaj Party 3 . CPI Communist Party of India 4 . CPM Communist Party of India (Marxist) 5 . INC Indian National Congress 6 . JD Janata Dal (Not to be used in General Elections, 1999) 7 . SAP Samata Party STATE PARTIES 8 . ICS Indian Congress (Socialist) 9 . INLD Indian National Lok Dal 10 . JP Janata Party 11 . LS Lok Shakti 12 . RJD Rashtriya Janata Dal 13 . RPI Republican Party of India 14 . SHS Shivsena 15 . SJP(R) Samajwadi Janata Party (Rashtriya) 16 . SP Samajwadi Party REGISTERED(Unrecognised ) PARTIES 17 . ABHM Akhil Bharat Hindu Mahasabha 18 . ABJS Akhil Bharatiya Jan Sangh 19 . ABLTC Akhil Bhartiya Lok Tantrik Congress 20 . ABMSD Akhil Bartiya Manav Seva Dal 21 . AD Apna Dal 22 . AJBP Ajeya Bharat Party 23 . BKD(J) Bahujan Kranti Dal (Jai) 24 .