Sustainable Agriculture – a New Partnership Paradigm in Dantewada Harsh Jaiswal, TERI University 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Being Neutral Is Our Biggest Crime”

India “Being Neutral HUMAN RIGHTS is Our Biggest Crime” WATCH Government, Vigilante, and Naxalite Abuses in India’s Chhattisgarh State “Being Neutral is Our Biggest Crime” Government, Vigilante, and Naxalite Abuses in India’s Chhattisgarh State Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-356-0 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org July 2008 1-56432-356-0 “Being Neutral is Our Biggest Crime” Government, Vigilante, and Naxalite Abuses in India’s Chhattisgarh State Maps........................................................................................................................ 1 Glossary/ Abbreviations ..........................................................................................3 I. Summary.............................................................................................................5 Government and Salwa Judum abuses ................................................................7 Abuses by Naxalites..........................................................................................10 Key Recommendations: The need for protection and accountability.................. -

Sukma, Chhattisgarh)

1 Innovative initiatives undertaken at . Cashless Village Palnar (Dantewada) . Comprehensive Education Development (Sukma, Chhattisgarh) . Early detection and screening of breast cancer (Thrissur) . Farm Pond On Demand (Maharashtra) . Integrated Solid Waste Management and Generation of Power from Waste (Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh) . Rural Solid Waste Management (Tamil Nadu) . Solar Urja Lamps Project (Dungarpur) . Spectrum Harmonization and Carrier Aggregation . The Neem Project (Gujarat) . The WDS Project (Surguja, Chhattisgarh) Executive Summary Cashless Village Palnar (Dantewada) Background/ Initiatives Undertaken • Gram Panchayat Palnar, made first cashless panchayat of the state • All shops enabled with cashless mechanism through Ezetap PoS, Paytm, AEPS etc. • Free Wi-Fi hotspot created at the market place and shopkeepers asked to give 2-5% discounts on digital transactions • “Digital Army” has been created for awareness and promotion – using Digital band, caps and T-shirts to attract localities • Monitoring and communication was done through WhatsApp Groups • Functional high transaction Common Service Centers (CSC) have been established • Entire panchayat has been given training for using cashless transaction techniques • Order were issued by CEO-ZP, Dantewada for cashless payment mode implementation for MNREGS and all Social Security Schemes, amongst multiple efforts taken by district administration • GP Palnar to also facilitate cashless payments to surrounding panchayats Key Achievements/ Impact • Empowerment of village population by building confidence of villagers in digital transactions • Improvement in digital literacy levels of masses • Local festivals like communal marriage, traditional folk dance festivals, inter village sports tournament are gone cashless • 1062 transactions, amounting to Rs. 1.22 lakh, done in cashless ways 3 Innovation Background Palnar is a village located in Kuakonda Tehsil of Dakshin Bastar Dantewada district in Chhattisgarh. -

Socio-Economic Survey Report of Villages in Dantewada

SOCIO-ECONOMIC SURVEY & NEEDS ASSESSMENT STUDY IN ESSAR STEEL’S PROJECT VILLAGE Baseline Report of the villages located in three blocks of Dantewada in South Bastar Survey Team of Essar Foundation Deepak David Dr. Tej Prakash Pratik Sethe Socio-economic survey and Need assessment study Kirandul, Dist. Dantewada- Chhattisgarh TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1. ESSAR STEEL INDIA LIMITED, VIZAG OPERATIONS - BENEFICIATION PLANT 1.2. ESSAR FOUNDATION 1.3. PROJECT LOCATION 1.4. OBJECTIVE 1.5. METHODOLOGY 1.6. STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT CHAPTER 2 AREA PROFILE 2.1. DISTRICT PROFILE 2.2. PROFILE OF THE VILLAGES 2.2.1. Location and Layout 2.2.2. Settlement pattern 2.2.3. Population 2.2.4. Sex Ratio 2.2.5. Literacy 2.2.6. Occupation 2.2.7. Education 2.2.8. Health services 2.2.9. Electrification 2.2.10. Road and transportation 2.2.11. Communication facilities CHAPTER 3 FINDING OF THE HOUSEHOLD SURVEY 3.1. BACKGROUND 3.2. METHODOLOGY 3.3. SOCIO- ECONOMIC PROFILES OF THE VILLAGES ESSAR FOUNDATION Page 2 of 86 Socio-economic survey and Need assessment study Kirandul, Dist. Dantewada- Chhattisgarh 3.3.1. # of HH members; Average # of members in HH 3.3.2. Caste/ Tribe and sub-group 3.3.3. Age- Sex Distribution 3.3.4. Marital Status 3.3.5. Literacy Rate 3.3.6. Migration 3.3.7. Occupation pattern 3.3.8. Employment and income 3.3.9. Dependency Ratio 3.3.10. Participation in Public Program 3.3.11. Livestock Population 3.3.12. -

Residential Schools for Children in LWE-Affected Areas of Chhattisgarh

EDUCATION 2.3 Pota Cabins: Residential schools for children in LWE-affected areas of Chhattisgarh Pota Cabins is an innovative educational initiative for building schools with impermanent materials like bamboo and plywood in Chhattisgarh. The initiative has helped reduce the number of out-of-school children and improve enrolment and retention of children since its introduction in 2011. The number of out-of-school children in the 6-14 years age group reduced from 21,816 to 5,780 as the number of Pota Cabins rose from 17 to 43 within a year of the initiative. These residential schools help ensure continuity of education from primary to middle-class levels in Left Wing Extremism affected villages of Dantewada district, by providing children and their families a safe zone where they can continue their education in an environment free of fear and instability. Rationale Secondly, it would also draw children away from the remote and interior areas of villages that are more prone to Left Wing Extremists violence. As these schools are perceived The status of education in Dantewada district of Chhattisgarh as places where children can receive adequate food and was abysmal. As per a 2005 report, the literacy rate of the education, they are often referred to Potacabins locally, as state stood at 30.2% against the state average of 64.7%.1 ‘pota’ means ‘stomach’ in the local Gondi language. The development deficit in the Dakshin Bastar area, which includes Dantewada district, has been largely attributed to the remoteness of villages, lack of proper infrastructure Objectives such as roads and bridges, and weak penetration of communication technology. -

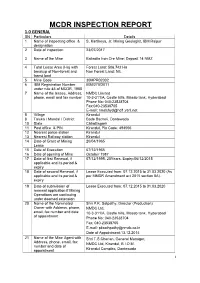

MCDR INSPECTION REPORT 1.0 GENERAL SN Particulars Details 1 Name of Inspecting Office & S

MCDR INSPECTION REPORT 1.0 GENERAL SN Particulars Details 1 Name of inspecting office & S. Kartikeya, Jr. Mining Geologist, IBM Raipur designation 2 Date of inspection 23/07/2017 3 Name of the Mine Bailadila Iron Ore Mine; Deposit 14 NMZ 4 Total Lease Area (Ha) with Forest Land: 506.742 Ha breakup of Non-forest and Non Forest Land: NIL forest land 5 Mine Code 30MPR02002 6 IBM Registration Number IBM/270/2011 under rule 45 of MCDR, 1988 7 Name of the lessee, Address, NMDC Limited phone, email and fax number 10-3-311/A, Castle hills, Masab tank, Hyderabad Phone No: 040-23538704 Fax:040-23538705 E-mail: [email protected] 8 Village Kirandul 8 Taluka / Mandal / District Bade Bacheli, Dantewada 10 State Chhattisgarh 11 Post office & PIN Kirandul, Pin Code: 494556 12 Nearest police station Kirandul 13 Nearest Railway station Kirandul 14 Date of Grant of Mining 20/04/1965 Lease 15 Date of Execution 07/12/1965 16 Date of opening of Mine October 1987 17 Date of first Renewal, if 07/12/1995, 20Years, Expiry-06/12/2015 applicable and its period & expiry 18 Date of second Renewal, if Lease Executed from: 07.12.2015 to 31.03.2020 (As applicable and its period & per MMDR Amendment act 2015 section 8A). expiry 19 Date of submission of Lease Executed from: 07.12.2015 to 31.03.2020 renewal application if Mining Operations are continuing under deemed extension 20 Name of the Nominated Shri P.K. Satpathy, Director (Production) Owner with Address, phone, NMDC Ltd, email, fax number and date 10-3-311/A, Castle hills, Masab tank, Hyderabad of appointment Phone No: 040-23538704 Fax: 040-23538705 E-mail: [email protected] Date of Appointment:13.12.2014 21 Name of the Mine Agent with Shri T.S.Cherian, General Manager, Address, phone, email, fax NMDC Ltd, Kirandul, B.I.O.M. -

Mineral Resource Department Directorate of Geology and Mining

MINERAL RESOURCE DEPARTMENT DIRECTORATE OF GEOLOGY AND MINING CHHATTISGARH DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT DANTEWADA INTRODUCTION Dantewada district is one of the Twenty Seven districts of Chhattisgarh State and Dantewada town is the administrative headquarters of this district. The Dantewada district occupies the southern part of Chhattisgarh state. Major part of the district falls in the Survey of India Degree Sheet No.65 F and is bounded between latitudes 17˚48’32”:19˚24’33”N and longitudes 80˚14’46”:82˚15’35”E. The total area of the district is approximately 3410.50 km2. Dantewada is connected with Jagadalpur the nearest town, by National Highway No.163 & 63. Dantewada is also connected by road with Hyderabad, the capital city of the neighboring state Telangana. Apart From Hyderabad Bus Connectivity is also available from two more major cities of Andhra Pradesh Vijayawada & Vishaka Pattanam. East coast Railway is running a regular train (Passanger) from Vishakha Pattanam to Bailadila which passes through the beautiful Araku Vally, and stops a while at Dantewada before reaching its destination Bailadila. The nearest Air terminal is Raipur. District survey report has been prepared as per the guidelines mentioned in appendix-10 of the notification No. S.O. 3611 (E) New Delhi, 25 January, 2016 of Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. This report has prepared by the Regional head, DGM Jagdalpur as per instructions issued by the Director, Geology & Mining (C.G.), Raipur by its letter no.5103-05/ geology-1/f.no.11/2015- 16, dated 22/04/2016. District survey report has been updated as per the guidelines mentioned in appendix-10 of the notification No. -

(AMDA) in India 1 | Page List of Municipal Councils and Municipalitie

Association of Municipalities and Development Authorities (AMDA) in India List of Municipal Councils and Municipalities in India S. No State Contact person, Address, Phone Website Name of Municipal Name of Municipality/Town and Email Id Council/Boards /Municipal Committees 1 Andhra Commissioner & Director of https://cdma.ap.gov.i 1. Adoni (M) 1. Addanki Pradesh Municipal Administration n/ulb-lists-0 2. Bhimavaram (M) 2. Allagadda Padmini Enclave, 5th lane, 4/7, 3. Chilakaluripet (M) 3. Amalapuram Mahatma Gandhi Inner Ring Rd, 4. Dharmavaram (M) 4. Amudalavalasa Annapura Nagar, Guntur, Andhra 5. Gudivada (M) 5. Atmakurknl Pradesh 522034 6. Guntakal (M) 6. Atmakurnlr Phone: 0866-2456708 7. Hindupur (M) 7. Bapatla Email: [email protected] 8. Madanapalle (M) 8. Bobbili 9. Nandyal (M) 9. Budwel 10. Narasaraopet (M) 10. Cheemakurthy 11. Proddatur (M) 11. Chirala 12. Tadepalligudem (M) 12. Dhone 13. Tadpatri (M) 13. Giddalur 14. Tenali (M) 14. Gollaprolu 15. Vizianagaram (M) 15. Gooty 16. Gudur-Kurnool 17. Gudur-SPR NELLORE 18. Ichapuram 19. Jaggaiahpet 20. Jammalamadugu 21. Jangareddygudem 22. Kavali 23. Kadiri 24. Kalyanadurgam 25. Kandukur 26. Kanigiri 27. Kovvur 28. Macherla 29. Madakasira 30. Mandapet 31. Mangalagiri 1 | P a g e Association of Municipalities and Development Authorities (AMDA) in India S. No State Contact person, Address, Phone Website Name of Municipal Name of Municipality/Town and Email Id Council/Boards /Municipal Committees 32. Markapur 33. Mummidivaram 34. Mydukur 35. Nagari 36. Naidupet 37. Nandigama 38. Nandikotkur 39. Narasapur 40. Narsipatnam 41. Nellimarla 42. Nidadavole 43. Nuzividu 44. Palakol 45. Palakonda 46. Palamaner 47. Palasakasibugga 48. -

List of Wards to Be Covered Under SKY

List of Wards to be covered under SKY # Ward Name Ward Code Town Name Town Code District Name Sub-District Name 1 Khairagarh (M) WARD NO.-0003 3 Khairagarh (M) 801989 Rajnandgaon Khairagarh 2 Jarhi (NP) WARD NO.-0008 8 Jarhi (NP) 801921 Surajpur Pratappur 3 Sinodha (OG) (Part) WARD NO.-0020 (Rural MDDS CODE:444897) 20 Tilda Newra (M + OG) 802038 Raipur Tilda 4 Jarhi (NP) WARD NO.-0009 9 Jarhi (NP) 801921 Surajpur Pratappur 5 Jarhi (NP) WARD NO.-0007 7 Jarhi (NP) 801921 Surajpur Pratappur 6 Benderchua (OG) WARD NO.-0042 (Rural MDDS CODE:434993) 42 Raigarh (M Corp. + OG) 801939 Raigarh Raigarh 7 Aamadi (NP) WARD NO.-0006 6 Aamadi (NP) 802051 Dhamtari Dhamtari 8 Wadrafnagar (NP) WARD NO.-0004 4 Wadrafnagar (NP) 801919 Balrampur Wadrafnagar 9 Jarhi (NP) WARD NO.-0006 6 Jarhi (NP) 801921 Surajpur Pratappur 10 Dornapal (NP) WARD NO.-0011 11 Dornapal (NP) 802072 Sukma Konta 11 Kishanpur (OG) (Part) WARD NO.-0047 (Rural MDDS CODE:434928) 47 Raigarh (M Corp. + OG) 801939 Raigarh Raigarh 12 Chhuriya (NP) WARD NO.-0010 10 Chhuriya (NP) 801992 Rajnandgaon Chhuriya 13 Parpondi (NP) WARD NO.-0004 4 Parpondi (NP) 802000 Bemetara Saja 14 Balrampur (NP) WARD NO.-0013 13 Balrampur (NP) 801918 Balrampur Balrampur 15 Pratappur (NP) WARD NO.-0003 3 Pratappur (NP) 801920 Surajpur Pratappur 16 Aamadi (NP) WARD NO.-0007 7 Aamadi (NP) 802051 Dhamtari Dhamtari 17 Birgaon (M) WARD NO.-0034 34 Birgaon (M) 802033 Raipur Raipur 18 Gurur (NP) WARD NO.-0008 8 Gurur (NP) 802019 Balod Gurur 19 Rajpur (NP) WARD NO.-0008 8 Rajpur (NP) 801929 Balrampur Rajpur 20 Birgaon (M) -

Political Map - Dantewada 81°11'0"E 81°22'0"E 81°33'0"E 81°44'0"E

0 1.5 3 6 9 12 Miles POLITICAL MAP - DANTEWADA 81°11'0"E 81°22'0"E 81°33'0"E 81°44'0"E Kemmar ! Hitawar ! Dawara ! !Darmuni N " Muchnar Hitameta N 0 ! ! ' Tumrigunda " 0 9 ! ' ° 9 9 Padmeta ° 1 ! 9 Cherpal 1 ! BARSUR ! Muchnar ! Lohandiguda ! i Kongur µ vat ! a dr Karkati In Pavanar ! ! Mustalnar Garsa ! Chhindnar Chhattisgarh State ! ! Upet ! BALRAMPUR KORIYA SURAJPUR Salnar Hidpal Gumalnar ! ! ! Chhindnar Korlapal SARGUJA ! ! JASHPUR Tarlapad KORBA ! Nagphani ! MUNGELI BILASPUR RAIGARH KABIRDHAM ! ! JANJGIR CHAMPA BEMETARA Joratari BALODABAZAR Nelgora ! ! Jaratari ! Gutoli ! RAIPUR DURG MAHASAMUND Bhairamgarh RAJNANDGAON Kanookarak ! BALOD Maphalnar Kasoli Katulnar DHAMTARI ! ! ! ! Madpal GARIABANDHr Karli Hiranar Marpal ! Bhutpadar! ! ! Ghotpal KANKER Bore Tumnar ! Nangul ! Hiranar ! Madse Bangapal Japori ! ! KONDAGAON ! ! Pedda Karli Ayatupara NARAYANPUR ! Sunarpara Bare Surekhi ! ! ! Kanapara ! BASTAR Samlur ! Madhapara BIJAPUR Darapal ! Suriyapara DANTEWADA ! ! Gidam ! N GIDAM ! " [ N 0 Kundenar " ' ! SUKMA 0 8 Siyanar ' ! Kankipara 5 ! 8 ° 5 8 Haram Jaunga ! ! ° 1 8 1 Haurnar ! Bastanar Chinna Karli Masodi Baram ! ! Binjam ! ! Gidam RS ! Handakodra Imlipara ! Pharaspal ! Muhander ! ! Bhagam Lahrapara ! ! Dabpal Gumda ! ! Chitalanka ! Midkulnar ! Tika Metta ! ! Alaikontapara ! Teknar Dalalbara ! ! ! ! Idwar ! Kotwalpara Kesapur ! Rundipara ! Aunrabhata ! Dumam ! ! ! Pondum Kawargaon Tudparas Tangrapadar ! ! ! DANTEWADA ! Katyarras! Lingopara Botampara ! DANTEWARA!Kosapara ! ! Kawalnar ! ! Dhakarapara Gondpal! Kulertong ! ! ! Degalras -

Alphabetical List of Towns and Their Population

ALPHABETICAL LIST OF TOWNS AND THEIR POPULATION CHHATTISGARH 1. Ahiwara (NP) [ CHH, Population: 18719, Class - IV ] 2. Akaltara (NP) [ CHH, Population: 20367, Class - III ] 3. Ambagarh Chowki (NP) [ CHH, Population: 8513, Class - V ] 4. Ambikapur UA [ CHH, Population: 90967, Class - II ] 5. Arang (NP) [ CHH, Population: 16629, Class - IV ] 6. Bade Bacheli (NP) [ CHH, Population: 20411, Class - III ] 7. Bagbahara (NP) [ CHH, Population: 16747, Class - IV ] 8. Baikunthpur (NP) [ CHH, Population: 10077, Class - IV ] 9. Balod (NP) [ CHH, Population: 21165, Class - III ] 10. Baloda (NP) [ CHH, Population: 11331, Class - IV ] 11. Baloda Bazar (NP) [ CHH, Population: 22853, Class - III ] 12. Banarsi (CT) [ CHH, Population: 10653, Class - IV ] 13. Basna (CT) [ CHH, Population: 8818, Class - V ] 14. Bemetra (NP) [ CHH, Population: 23315, Class - III ] 15. Bhatapara (M) [ CHH, Population: 50118, Class - II ] 16. Bhatgaon (NP) [ CHH, Population: 8228, Class - V ] 17. Bilaspur UA [ CHH, Population: 335293, Class - I ] 18. Bilha (NP) [ CHH, Population: 8988, Class - V ] 19. Birgaon (CT) [ CHH, Population: 23562, Class - III ] 20. Bodri (NP) [ CHH, Population: 13403, Class - IV ] 21. Champa (M) [ CHH, Population: 37951, Class - III ] 22. Chharchha (CT) [ CHH, Population: 15217, Class - IV ] 23. Chhuikhadan (NP) [ CHH, Population: 6418, Class - V ] 24. Chirmiri UA [ CHH, Population: 93373, Class - II ] 25. Dalli-Rajhara UA [ CHH, Population: 57058, Class - II ] 26. Dantewada (NP) [ CHH, Population: 6641, Class - V ] 27. Dhamdha (NP) [ CHH, Population: 8577, Class - V ] 28. Dhamtari (M) [ CHH, Population: 82111, Class - II ] List of towns: Census of India 2001 Chhattisgarh – Page 1 of 4 CHHATTISGARH (Continued): 29. Dharamjaigarh (NP) [ CHH, Population: 13598, Class - IV ] 30. Dipka (CT) [ CHH, Population: 20150, Class - III ] 31. -

Issance Survey/Prospecting & Exploration, Mine Planning

Reconnaissance Survey/Prospecting & Exploration, Mine Planning ISO 9001:2008 Certified SIDDHARTH GEOCONSULTANTS & An ISO 9001:2008 Certified Company SIDDHARTH GEO CONSULTANTS (I) PVT.LTD. 621/3 FIRST FLOOR, RAMKUND, SAMTA COLONY, BEHIND LIFE WORTH HOSPITAL, RAIPUR, CHHATTISGARH, INDIA Phone-0771-4070731 Fax- 0771 - 4281072, E –mail: [email protected]& [email protected] Website: www.mininggeology-sgc.com 1. RECONNAISSANCE SURVEY We have a team of experienced experts to deal with all type of Technical and Legal procedures needed to perform Reconnaissance. The process includes not only the field work but also various Government procedures as under: Application for Reconnaissance Permit (R.P.). Preparation and submission of Scheme. Geo-physical survey. Detailed Geological Mapping. Sampling & Analysis. Data interpretation. Mineral & Area selection for Prospecting License (P.L.). R.P. Projects RP over an Area of 907 Sq Km for Gold, Diamond, Base Metal, and Precious & Semi-Precious Gem Stone, Rare Earth Minerals etc. in Sidhi District of MP State for Rag Mines Pvt. Limited Raipur. RP over an Area of 1354 Sq. Km. for Diamond, Gold, Base Metal, & Semi-precious Gem Stone in Bijapur District. RP sanctioned to Major Anil Singh (Partner of Siddharth Geo Consultants), Raipur. RP over an Area of 522 Sq Km for Gold, Diamond, Base Metal, and Precious & Semi-Precious Gem Stone, Rare Earth Minerals etc. in Sidhi District of MP State for Rag Mines Pvt. Limited Raipur. 2. PROSPECTING AND EXPLORATION Preparation and Submission of P.L. application. Preparation of Prospecting Scheme as per UNFC guidelines. Topographical and DGPS Survey. Detail Geological Mapping. Geophysical Survey. -

Naxalism: the Maoist Challenge to the Indian State

Naxalism: The Maoist Challenge to the Indian State Written by Lennart Bendfeldt, HBF intern, July 2010 Abstract The Naxalite armed movement challenges the Indian state since more than 40 years. It is based on Maoist ideology and gains its strength through mobilizing the poor, underprivileged, discouraged and marginalized, especially in rural India. The Naxalite movements are a serious threat for the Indian State: They are now active in 223 districts in 20 states and the strength of their armed cadres is estimated between 10.000 and 20.000. Due to the Naxalite’s control over certain areas and their armed fight against the state security forces, they are challenging the inherent ideals of the state, namely sovereignty and monopoly on the use of force. In order to correspond with its ideal, the state focuses on the re-establishment of law and order by encountering the Naxalites violently. However, the movement’s roots are located within India’s numerous social and economic inequalities as well as in environmental degradation. Without fostering the root causes the state will not be able to solve the problem. This paper is divided into three parts and tries to give an extensive overview of the complex issue of the Naxalite conflict. Therefore the first part deals with the history of the movement by describing its origin and development until today. Part two deals with the strategy and actions of the Naxalites and sets its focus on the root causes. The final third part covers the state’s responses and the limitations of the state in the embattled regions.