Law and Religion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Marranos

The Marranos A History in Need of Healing Peter Hocken www.stucom.nl doc 0253uk Copyright © 2006 Toward Jerusalem Council II All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written consent of Toward Jerusalem Council II. Short extracts may be quoted for review purposes. Scripture quotations in this publication are taken from Revised Standard Version of the Bible Copyright © 1952 [2nd edition, 1971] by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. 2 www.stucom.nl doc 0253uk Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................... 5 Part I: The Spanish Background ............................................ 9 Part II: The Marranos and the Inquisition .............................. 13 Part III: The Life of the Crypto-Jews .................................... 29 Part IV: The Issues for Toward Jerusalem Council II ............. 47 Epilogue ............................................................................... 55 3 www.stucom.nl doc 0253uk 4 www.stucom.nl doc 0253uk Introduction This booklet on the Marranos, the Jews of Spain, Portugal and Latin America baptized under duress, is the third in the series of the TJCII (Toward Jerusalem Council II) booklets. TJCII was launched in 19961. In March 1998 the committee members and a group of in- tercessors made a prayer journey to Spain, visiting Granada, Cordoba and Toledo. From this time the TJCII leadership knew that one day we would have to address the history and sufferings of the Marranos. An explanatory note is needed about the terminology. -

I Ask, Then, Has God Rejected His People? by No Means! for I Myself Am an Israelite, a Descendant of Abraham, a Member of the Tribe of Benjamin

Romans 11:1-2a, 13-14, and 28-32 “People who Live by God’s Proclamation” I ask, then, has God rejected his people? By no means! For I myself am an Israelite, a descendant of Abraham, a member of the tribe of Benjamin. 2 God has not rejected his people whom he foreknew… 13 Now I am speaking to you Gentiles. Inasmuch then as I am an apostle to the Gentiles, I magnify my ministry 14 in order somehow to make my fellow Jews jealous, and thus save some of them… 28 As regards the gospel, they are enemies for your sake. But as regards election, they are beloved for the sake of their forefathers. 29 For the gifts and the calling of God are irrevocable. 30 For just as you were at one time disobedient to God but now have received mercy because of their disobedience, 31 so they too have now been disobedient in order that by the mercy shown to you they also may now receive mercy. 32 For God has consigned all to disobedience, that he may have mercy on all. In American Christianity, Romans 11 has often been torn apart. You can find bits and pieces of it scattered about on the Internet, on various websites speaking about the end times and the restoration of Israel. These verses are joined to prophecies from Daniel, visions from Ezekiel, and images from Revelation. They are joined to doomsday predictions and headlines from newspapers, wars and rumors of wars in the Holy Land. With strong language and even stronger fervor, various Christian organizations fight for the nation of Israel. -

Tablet Features Spread 14/04/2020 15:17 Page 13

14_Tablet18Apr20 Diary Puzzles Enigma.qxp_Tablet features spread 14/04/2020 15:17 Page 13 WORD FROM THE CLOISTERS [email protected] the US, rather than given to a big newspaper, Francis in so that Francis could address the people of God directly, unfiltered. He had been gently the garden rebuffed. So the call from the Pope’s Uruguayan priest secretary, Fr Gonzalo AUSTEN IVEREIGH tells us he was in his Aemilius, a week later was a delightful shock: garden and just about to plant a large jasmine “Would it be alright if the Holy Father when the audio file arrived in his inbox. It recorded his answers to your questions?” The was the voice of Pope Francis, who had complete interview appeared in last week’s agreed to record his answers to the questions Easter issue of The Tablet. Ivereigh had put to him about navigating our way through the coronavirus storm. LAST YEAR Austen and his wife Linda and Ivereigh decided to put his headphones on their dogs deserted south Oxfordshire for a and listen to the Pope speaking to him while small farm near Hereford, with charmingly he was digging. By the time the plant was decayed old barns and 15 acres of grass mead- in the ground, watered and mulched, Francis ows, at the edge of a hamlet off a busy road was still only halfway through the third to Wales. He blames Laudato Si’ . The Brecon answer. “I checked the recording,” Austen Ivereigh, who was deputy editor of The Beacons beckon from a far horizon; the Wye, says, “46 minutes!” Tablet in the long winter of the John Paul II swelled by fast Welsh rivers, courses close by; “By the end I was stunned. -

The 18Th International Congress of Jesuit Ecumenists”

“The 18th International Congress of Jesuit Ecumenists” ................................................................. 2 “Conversion to Interreligious Dialogue.....”, James T. Bretzke, S.J. ................................................. 2 “The Practice of Daoist (Taoist) Compassion”, Michael Saso, S.J. .................................................. 3 “Kehilla, Church and Jewish people”, David Neuhaus, S.J. ............................................................. 6 “Let us Cross Over the Other Shore”, Christophe Ravanel, S.J. ………………………………….….10 “Six Theses on Islam in Europe”, Groupe des Deux Rives……………………………………….11 “Meeting of Jesuits in Islamic Studies, September 2006” .............................................................. 13 “Encounter and the Risk of Change”, Wilfried Dettling, S.J. ......................................................... 14 Secretariat for Interreligious Dialogue; Curia S.J., C.P. 6139, 00195 Roma Prati, Italy; N.11 tel. (39) 06.689.77.567/8; fax: 06.689.77.580; e-mail: [email protected] 2006 4 Vatican II, through the conceptual revolution THE 18TH INTERNATIONAL in ecumenical appreciation produced by CONGRESS OF Unitatis Redintegratio, and into the more JESUIT ECUMENISTS recent involvement of Jesuits in the ecumenical movement since the time of the Second Vatican Council. Edward Farrugia The Jesuit Ecumenists are an informal group looks at a specific issue that lies at the heart of Jesuit scholars active in the movement for of Catholic-Orthodox relations, that of the Christian unity who have -

Are Jewish Converts Still Jewish?

Are Jewish Converts still Jewish? Interview with David Moss Ed. Faith magazine’s Patrick O’Brien interviewed David Moss, President of the Association of Hebrew Catholics (AHC). The AHC relocated to Ypsilanti, Michigan in Sept. 2001. [The interview below reflects some modifications made to fit a flyer produced by the AHC. The full interview may be found at http://www.faithmag.com/issues/mar02.html#cover]. Some people thought our February issue headline: ‘A Catholic Deacon Born Jewish’ implied that Deacon Warren Hecht was no longer Jewish. Is he? Well, the term Jew is ambiguous the way it is normally used. Sometimes it refers to a person’ religious practices and sometimes to a person’s ethnicity. Deacon Warren’s religious practices are not those of a Jew but of a Catholic. However, Deacon Warren remains a member of the Jewish people, or more properly, the People Israel. This is the people that descend from Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. In their religious faith and practice, they may be Catholics, Rabbinical Jews, Protestants, or something else. Many Jews don’t like to be called converts since they already believed in God, and in their religious observances, they were already responding to that part of the Word of God in the Tanakh, or what we call the Old Testament. When we recognize the Messiah and enter His Church, we fulfill or complete our Old Testament Faith. But we do not lose our ethnicity, who we are. For clarity’s sake (since we do not practice Judaism) and to not offend our Jewish brothers and sisters, we do not use the term Jewish Catholic. -

Mary and the Catholic Church in England, 18541893

bs_bs_banner Journal of Religious History Vol. 39, No. 1, March 2015 doi: 10.1111/1467-9809.12121 CADOC D. A. LEIGHTON Mary and the Catholic Church in England, 1854–1893 The article offers description of the Marianism of the English Catholic Church — in particular as manifested in the celebration of the definition of the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception in 1854 and the solemn consecration of England to the Virgin in 1893 — in order to comment on the community’s (and more particularly, its leadership’s) changing perception of its identity and situation over the course of the later nineteenth century. In doing so, it places particular emphasis on the presence of apocalyptic belief, reflective and supportive of a profound alienation from con- temporary English society, which was fundamental in shaping the Catholic body’s modern history. Introduction Frederick Faber, perhaps the most important of the writers to whom one should turn in attempting to grasp more than an exterior view of English Catholicism in the Victorian era, was constantly anxious to remind his audiences that Marian doctrine and devotion were fundamental and integral to Catholicism. As such, the Mother of God was necessarily to be found “everywhere and in everything” among Catholics. Non-Catholics, he noted, were disturbed to find her introduced in the most “awkward and unexpected” places.1 Faber’s asser- tion, it might be remarked, seems to be extensively supported by the writings of present-day historians. We need look no further than to writings on a sub-theme of the history of Marianism — that of apparitions — and to the period spoken of in the present article to make the point. -

The Tablet June 2011 Standing of Diocese’S Schools and Colleges Reflected in Rolls

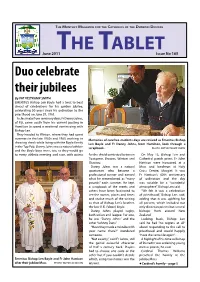

THE MON T HLY MAGAZINE FOR T HE CA T HOLI C S OF T HE DUNE D IN DIO C ESE HE ABLE T June 2011T T Issue No 165 Duo celebrate their jubilees By PAT VELTKAMP SMITH EMERITUS Bishop Len Boyle had a treat to beat ahead of celebrations for his golden jubilee, celebrating 50 years since his ordination to the priesthood on June 29, 1961. A classmate from seminary days, Fr Danny Johns, of Fiji, came south from his current posting in Hamilton to spend a weekend reminiscing with Bishop Len. They headed to Winton, where they had spent summers in the late 1950s and 1960, working in Memories of carefree students days are revived as Emeritus Bishop shearing sheds while living with the Boyle family Len Boyle and Fr Danny Johns, from Hamilton, look through a in the Top Pub. Danny Johns was a natural athlete scrapbook. PHOTO: PAT VELTKAMP SMITH and the Boyle boys were, too, so they would go to every athletic meeting and race, with points for the shield contested between On May 13, Bishop Len and Tuatapere, Browns, Winton and Cathedral parish priest Fr John Otautau. Harrison were honoured at a Danny Johns was a natural Mass and luncheon at Holy sportsman who became a Cross Centre, Mosgiel. It was professional runner and earned Fr Harrison’s 40th anniversary what he remembered as “many of ordination and the day pounds’’ each summer. He kept was notable for a “wonderful a scrapbook of the meets and atmosphere”, Bishop Len said. others have been fascinated to “We felt it was a celebration see the names, places and times of priesthood,” Bishop Len said, and realise much of the writing adding that it was uplifting for as that of Bishop Len’s brother, all present, which included not the late V. -

Thehebrewcatholic

Publication of the Association of Hebrew Catholics No. 78, Winter Spring 2003 TheTheTheTheTheThe HebrewHebrewHebrewHebrewHebrewHebrew CatholicCatholicCatholicCatholicCatholicCatholic “And so all Israel shall be saved” (Romans 11:26) Our new web site http://hebrewcatholic.org The Hebrew Catholic, No. 78, Winter Spring 2003 1 Association of Hebrew Catholics ~ International The Association of Hebrew Catholics aims at ending the alienation Founder of Catholics of Jewish origin and background from their historical Elias Friedman, O.C.D., 1916-1999 heritage, by the formation of a Hebrew Catholic Community juridi- Spiritual Advisor cally approved by the Holy See. Msgr. Robert Silverman (United States) The kerygma of the AHC announces that the divine plan of salvation President has entered the phase of the Apostasy of the Gentiles, prophesied by David Moss (United States) Our Lord and St. Paul, and of which the Return of the Jews to the Secretary Holy Land is a corollary. Andrew Sholl (Australia) Advisory Board Msgr. William A. Carew (Canada) “Consider the primary aim of the group to be, Nick Healy (United States) not the conversion of the Jews but the creation of a new Hebrew Catholic community life and spirit, Association of Hebrew Catholics ~ United States an alternative society to the old.” David Moss, President A counsel from Elias Friedman, O.C.D. Kathleen Moss, Secretary David Moss, (Acting) Treasurer The Association of Hebrew Catholics (United States) is a non-profit corpo- The Association of Hebrew Catholics is under the patronage of ration registered in the state of New York. All contributions are tax deduct- Our Lady of the Miracle ible in accordance with §501(c)(3) of the IRS code. -

Thehebrewcatholic

Publication of the Association of Hebrew Catholics No. 99, Spring 2016 TheThe HebrewHebrew CatholicCatholic “And so all Israel shall be saved” (Romans 11:26) The Mass of St. Pope Gregory, Israhel van Meckenem, 1457-1470 (http://www.zeno.org/nid/20004163710) Association of Hebrew Catholics ~ International The Association of Hebrew Catholics aims at ending the alienation of Founder Catholics of Jewish origin and background from their historical heritage. Elias Friedman, O.C.D., 1916-1999 By gathering the People Israel within the Church, the AHC hopes to help Co-founder enable them to serve the Church and all peoples within the mystery of their Andrew Sholl (Australia) irrevocable gifts and calling. (cf. Rom. 11:29) Spiritual Advisor The kerygma of the AHC announces that the divine plan of salvation has Fr. Ed. Fride (United States) entered the phase of the Apostasy of the Gentiles, prophesied by Our Lord and President St. Paul, and of which the Return of the Jews to the Holy Land is a corollary. David Moss (United States) Secretary Kathleen Moss (United States) “Consider the primary aim of the group to be, Director of Theology not the conversion of the Jews, Lawrence Feingold S.T.D. S.T.L. (United States) but the creation of a new Hebrew Catholic community life and spirit, Advisory Board an alternative society to the old.” Card. Raymond Burke, Dr. Robert Fastiggi, A counsel from Elias Friedman, O.C.D. Fr. Peter Stravinskas, Fr. Jerome Treacy SJ, “The mission of your association responds, in a most fitting way, Dr. Andre Villeneuve to the desire of the Church to respect fully The Association of Hebrew Catholics (United States) is a non-profit corpora- the distinct vocation and heritage of Israelites in the Catholic Church.” tion registered in the state of New York, Michigan & Missouri. -

Tablet Features Spread

175 YEARS – 50 GREAT CATHOLICS / Carmen Mangion on Sr Mary Clare Moore Born in Dublin To mark our anniversary, we have invited 50 Catholics to choose adored. In October 1854 she led on 20 March a person from the past 175 years whose life has been a personal a party of four Bermondsey sisters 1814, Georgiana inspiration to them and an example of their faith at its best to join Nightingale to nurse in the Moore converted Crimea. Jerry Barrett’s painting to Catholicism the first four women to join her, the leaders that founded nine Mission of Mercy: Florence with her mother taking the name Mary Clare. Convents of Mercy in England. Nightingale receiving the wounded in 1823. Aged Aged 23, Moore became supe- She worked well with the at Scutari (in the National Portrait 14, she was rior of the Cork convent. Then in English hierarchy, becoming a Gallery) gives us our only contem- employed by the founder of the 1839, she was lent to the first close and trusted confidante of porary image of her. Her face, like Sisters of Mercy, Catherine English foundation in the slums Thomas Grant, the Bishop of her life, is in the shadows. McAuley, as a governess but was of Bermondsey, south London. Southwark. Her letters to her sis- Mary Clare Moore died of soon drawn by her House of She managed the Convent of ters reflect her compassion and pleurisy in 1874, aged only 60, Mercy, a refuge and school for Mercy in Bermondsey until her encouragement. She wrote to con- but worn out by her exertions on impoverished female servants death in 1874. -

Jesus Christ's Sufferings and Death in the Iconography of the East and the West

Скрижали, 4, 2012, с. 122-138 V.V.Akimov Jesus Christ's sufferings and death in the iconography of the East and the West The image of God sufferings, Jesus Christ crucifixion has received such wide spreading in the Christian world that is hardly possible to count up total of the similar monuments created throughout last one and a half thousand of years. The crucifixion has got a habitual symbol of Christianity and various types of the Crucifix became a distinctive feature of some Christian faiths. From time to time modern Christians, looking at the Cross with crucified Jesus Christ, don’t think of the tragedy of Christ’s death and the joy of His resurrection but whether the given Crucifix is «their own» or «another's». Meanwhile, the iconography of the Crucifix as far as the iconography of God’s Mother can testify to a generality of Christian tradition of the East and the West. There are much more general lines than differences between them. The evangelical narration of God sufferings and the history of Crucifix iconography formation, both of these, testify to the unity of east and western tradition of the image of the Crucifixion. Traditions of the East and the West had one source and were in constant interaction. Considering the Crucifix iconography of the East and the West in a context of the evangelical narration and in a historical context testifies to the unity of these traditions and leads not to dissociation, conflicts and mutual recriminations, but gives an impulse to search of the lost unity. -

The Catholic Church and Toward Jerusalem Council II Presentation at UMJC Conference, Baltimore

1 Confronting Past Injustice: The Catholic Church and Toward Jerusalem Council II Presentation at UMJC Conference, Baltimore: July 17, 2015 I am very happy to accept this invitation to come and share about TJCII (Toward Jerusalem Council II) at this UMJC conference. First, because there were strong UMJC connections in the birth of TJCII. Marty Waldman was president at that time, and one of his first supporters was Dan Juster. But a second reason is my appreciation for the work of Mark Kinzer with which you will be familiar. One reason for this appreciation is my perception that Mark is in a key way the theologian of TJCII – a role so far not yet understood by all involved in the initiative! It is Mark who has articulated most clearly a bipartite ecclesiology, the vision of the Church made up of Jews and non-Jews, retaining their distinctiveness, but made one through the blood of the cross. But this bipartite ecclesiology is in effect the theological foundation of Toward Jerusalem Council II. For the TJCII vision is one of the restoration of this one Church of both Jew and Gentile, with a second Jerusalem council being a coming together in unity of both expressions of the Church in full mutual recognition and rightful honoring. The rightful honoring is a work of restitution. The past injustice of scorn and contempt was the exact opposite of honoring. Another reason why Mark Kinzer is a key theologian for TJCII is his recognition of the necessary role of the Catholic Church, with his knowledge of the Catholic tradition gained especially during his years working with Steve Clark at Ann Arbor.