Transcript(PDF 68.39

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Be, Or Not to Be? the Role of the Unconscious in Transgender Transitioning: Identity, Autonomy and Well-Being

Extended essay To be, or not to be? The role of the unconscious in J Med Ethics: first published as 10.1136/medethics-2021-107397 on 30 July 2021. Downloaded from transgender transitioning: identity, autonomy and well- being Alessandra Lemma,1 Julian Savulescu 2,3,4 1Visiting Professor, ABSTRACT yet gone through puberty are not able to properly Psychoanalysis Unit, University The exponential rise in transgender self- identification understand the ‘lifelong medical, psychological and College London, London, UK 2 emotional implications’ of taking puberty blockers Faculty of Philosophy, invites consideration of what constitutes an ethical University of Oxford, Oxford, UK response to transgender individuals’ claims about how and cross- sex hormones; and second, the experi- 3Biomedical Ethics Research best to promote their well- being. In this paper, we mental nature of puberty blockers specifically, with Group, Murdoch Childrens argue that ’accepting’ a claim to medical transitioning potentially significant unknown side effects and Research Institute, Parkville, 3 in order to promote well- being would be in the person’s little evidence of long-term benefits. In practice, Victoria, Australia 4Melbourne Law School, best interests iff at the point of request the individual this ruling now forbids the prescription of puberty University of Melbourne, is correct in their self- diagnosis as transgender (i.e., suppressants without court order. This particular Melbourne, Victoria, Australia the distress felt to reside in the body does not result ruling is in the process of being challenged by the from another psychological and/or societal problem) GID. A more recent 2021 court order allows for Correspondence to such that the medical interventions they are seeking the prescription as long as there is parental consent. -

Future of Genetics Julian Savulescu

Doha Debate 8: Future of Genetics Lesson Plan 4a - Julian Savulescu FLEXIBLE INSTRUCTION This lesson and related activities are designed to support in-class learning, elearning, and distance learning (students working online at home while the instructor checks in digitally.) STAGE 1: DESIRED GOALS ESTABLISHED GOAL Demonstrate an understanding of how genetic human enhancement is a moral obligation going into the future. MEANING UNDERSTANDINGS ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS Students will understand that... What is the importance of human wellbeing? Gene editing can give the next generation a In what ways does nature not allocate genes equally better life. in humans? We already use biological interventions. How is wellbeing appealed to in daily life? People can already avoid certain genetic Which biological interventions are already being disorders with gene editing. used? There will need to be strong ethical How are people able to avoid genetic disorders with principles around gene editing. current technology? The promotion of wellbeing should be the Why might we not need as much genetic diversity as central idea behind gene editing. we once did? What role does ethics play in human enhancement? How might our species change with gene editing? ACQUISITION Students will know... Students will be able to... Key issues surrounding the future of Explain how gene editing is a moral obligation. human enhancement through gene Describe ways gene editing has the potential to editing. create a new species of humans. Differing ways gene enhancement may benefit people. ProjectExplorer x Doha Debates, 2020 ENGAGEMENT Students will.. Learn about what choices you might make if you had the opportunity to choose what you look like. -

Ethical Issues in Human Enhancement

Ethical Issues in Human Enhancement Nick Bostrom Rebecca Roache (2008) [Published in New Waves in Applied Ethics, eds. Jesper Ryberg, Thomas Petersen & Clark Wolf (Pelgrave Macmillan, 2008): pp. 120-152] www.nickbostrom.com What is Human Enhancement? Human enhancement has emerged in recent years as a blossoming topic in applied ethics. With continuing advances in science and technology, people are beginning to realize that some of the basic parameters of the human condition might be changed in the future. One important way in which the human condition could be changed is through the enhancement of basic human capacities. If this becomes feasible within the lifespan of many people alive today, then it is important now to consider the normative questions raised by such prospects. The answers to these questions might not only help us be better prepared when technology catches up with imagination, but they may be relevant to many decisions we make today, such as decisions about how much funding to give to various kinds of research. Enhancement is typically contraposed to therapy. In broad terms, therapy aims to fix something that has gone wrong, by curing specific diseases or injuries, while enhancement interventions aim to improve the state of an organism beyond its normal healthy state. However, the distinction between therapy and enhancement is problematic, for several reasons. First, we may note that the therapy-enhancement dichotomy does not map onto any corresponding dichotomy between standard-contemporary-medicine and medicine- as-it-could-be-practised-in-the-future. Standard contemporary medicine includes many practices that do not aim to cure diseases or injuries. -

The Ethics of Human Enhancement

Philosophy Compass 10/4 (2015): 233–243, 10.1111/phc3.12208 The Ethics of Human Enhancement Alberto Giubilini1* and Sagar Sanyal2 1Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics, Charles Sturt University 2Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics, University Of Melbourne Abstract Ethical debate surrounding human enhancement, especially by biotechnological means, has burgeoned since the turn of the century. Issues discussed include whether specific types of enhancement are permis- sible or even obligatory, whether they are likely to produce a net good for individuals and for society, and whether there is something intrinsically wrong in playing God with human nature. We characterize the main camps on the issue, identifying three main positions: permissive, restrictive and conservative posi- tions. We present the major sub-debates and lines of argument from each camp. The review also gives a f lavor of the general approach of key writers in the literature such as Julian Savulescu, Nick Bostrom, Michael Sandel, and Leon Kass. 1. Introduction Human enhancement in contemporary philosophical debate refers to biomedical interventions to improve human capacities, performances, dispositions, and well-being beyond the traditional scope of therapeutic medicine. Some forms of enhancement, such as doping in sport or the pharmaceutical improvement of memory and attention span, are already feasible. Others might be available in the near future, such as genetic engineering to increase cognitive capacities. The ethical issues that arise include whether specific enhancements are permissible, obligatory, or a net good for individuals and for society. Positions in the debate span a continuum between permissive and restrictive views. Authors holding the most permissive positions have no objections to a wide range of enhancements, such as the ones already mentioned. -

Transhumanism and Its Critics on the Ethics of Enhancement Via Brain-Computer Interfacing

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 4-17-2014 12:00 AM Cultivating Better Brains: Transhumanism and its Critics on the Ethics of Enhancement Via Brain-computer Interfacing Matthew Devlin The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Tim Blackmore The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Media Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Matthew Devlin 2014 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Devlin, Matthew, "Cultivating Better Brains: Transhumanism and its Critics on the Ethics of Enhancement Via Brain-computer Interfacing" (2014). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 1946. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/1946 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CULTIVATING BETTER BRAINS: TRANSHUMANISM AND ITS CRITICS ON THE ETHICS OF COGNITIVE ENHANCEMENT VIA BRAIN-COMPUTER INTERFACING (Thesis format: Monograph) by Matthew Devlin Graduate Program in Media Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Matthew Devlin 2014 Abstract Transhumanists contend that enhancing the human brain—a subfield of human enhancement called cognitive enhancement—is both a crucial and desirable pursuit, supporting the cultivation of a better world. -

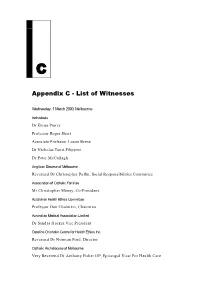

Appendix C - List of Witnesses 259

& $SSHQGL[&/LVWRI:LWQHVVHV Wednesday, 1 March 2000, Melbourne Individuals Dr Eloise Piercy Professor Roger Short Associate Professor Loane Skene Dr Nicholas Tonti-Filippini Dr Peter McCullagh Anglican Diocese of Melbourne Reverend Dr Christopher Pullin, Social Responsibilities Committee Association of Catholic Families Mr Christopher Meney, Co-President Australian Health Ethics Committee Professor Don Chalmers, Chairman Australian Medical Association Limited Dr Sandra Hacker,Vice President Caroline Chisholm Centre for Health Ethics Inc. Reverend Dr Norman Ford, Director Catholic Archdiocese of Melbourne Very Reverend Dr Anthony Fisher OP, Episcopal Vicar For Health Care 258 HUMAN CLONING Council for Marriage and the Family Ms Jennifer Weber, Secretary Howard Florey Institute, University of Melbourne Professor Felix Beck, Consultant Human Genetics Society of Australia Dr John Rogers, Chairman, Ethics and Social Issues Committee Humanist Society of Victoria Inc Dr Alan McPhate, President Ms Halina Strnad, Convenor, Submissions Group Monash Institute of Reproduction and Development Professor Marilyn Monk, Senior Scientist Associate Professor Martin Pera, Senior Research Fellow Professor Alan Trounson, Deputy Director Monash Medical Centre Dr Geoffrey Matthews, Chairman, Human Research and Ethics Committee Ovulation Method Research and Reference Centre of Australia Dr Mary Walsh, President Plunkett Centre for Ethics in Health Care Dr Bernadette Tobin, Director Right to Life Australia Ms Margaret Tighe, Chairwoman Southern Cross Bioethics -

Doctors Have No Right to Refuse Medical Assistance in Dying, Abortion Or Contraception

bs_bs_banner Bioethics ISSN 0269-9702 (print); 1467-8519 (online) doi:10.1111/bioe.12288 Volume 31 Number 3 2017 pp 162–170 DOCTORS HAVE NO RIGHT TO REFUSE MEDICAL ASSISTANCE IN DYING, ABORTION OR CONTRACEPTION JULIAN SAVULESCU AND UDO SCHUKLENK Keywords autonomy, ABSTRACT professionalism, In an article in this journal, Christopher Cowley argues that we have ‘misun- interests, derstood the special nature of medicine, and have misunderstood the moti- justice, vations of the conscientious objectors’.1 We have not. It is Cowley who has law, misunderstood the role of personal values in the profession of medicine. euthanasia We argue that there should be better protections for patients from doctors’ personal values and there should be more severe restrictions on the right to conscientious objection, particularly in relation to assisted dying. We argue that eligible patients could be guaranteed access to medical services that are subject to conscientious objections by: (1) removing a right to con- scientious objection; (2) selecting candidates into relevant medical special- ities or general practice who do not have objections; (3) demonopolizing the provision of these services away from the medical profession. REASONABLE ARGUMENTS’LACKOF resulted in horrific side effects for the woman, including TRACTION EXPLAINED gross incontinence, pain and restricted mobility, but was performed in many cases without consent, without even Cowley begins his defence of conscientious objection by informing the patient, in part because Catholic doctors conceding: Schuklenks arguments appear very reasona- believed that a Caesarean section might impede the ble, and his concern for patients is genuine. What he and womans ability to have the maximum number of chil- Savulescu lack is an explanation of why their arguments dren possible in the future.3 have failed to move legislators or professional bodies.2 In fact, Cowley is wrong that no countries have To the extent that this is true, the answer is obvious: rejected a right to conscientious objection. -

The Principle of Procreative Beneficence Is Eugenic, but So What?

The Principle of Procreative Beneficence is Eugenic, but so what? by Andrew Hotke A thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in Philosophy in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada September, 2012 Copyright © Andrew Hotke, 2012 Abstract In response to the possibilities for selection created by reproductive technologies like IVF and Prenatal screening, Julian Savulescu has argued that parents have a moral obligation to employ selective technology in order to have the best child that they can possibly have. This idea, which Savulescu has called the Principle of Procreative Beneficence, appears reminiscent of historical eugenics. However, Savulescu has argued that this principle is not eugenic. In this paper I argue that there are good reasons to think that the Principle of Procreative Beneficence is eugenic. Specifically, I argue that this principle shares five common features with historical eugenics which justify the conclusion that it is eugenic. However, while I argue that this principle is eugenic, I argue that it is not morally problematic for that reason because the shared features of historical eugenics and the Principle of Procreative Beneficence, which justify the claim that the principle is eugenic, are not morally problematic. II Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction....................................................................................................................1 Chapter 2: The Principle of Procreative Beneficence......................................................................4 -

The Concept of “Autonomy” and Its Relationship with the Idea of Transhumanism

International Journal of Social and Educational Innovation (IJSEIro) Volume 2 / Issue 3/ 2015 The Concept of “Autonomy” And Its Relationship with the Idea of Transhumanism TEREC-VLAD Loredana Stefan cel Mare University of Suceava, Romania E-mail: [email protected] Received 29.01.2015; Accepted 12.02. 2015 Abstract Medicine has a lot of principles that need to be complied with especially when it comes to saving the life of the individual and, at the same time, respecting his rights. Today there are increasingly more cases of malpraxis either because these principles are not fully complied with or out of negligence. We believe that one of the most important principles of medicine is autonomy, whereas it is essential for the individual to act in accordance with his principles and values or those of the society where he lives. In this paper I shall analyze the concept of autonomy and its relationship with transhumanism. I shall argue that within human enhancement - whether cognitive enhancement or human enhancement - the individual must be autonomous and must be able to decide regarding his maximum benefit. We believe that human bioenhancement is a project that – when put into practice - could have negative consequences, since moral enhancement is rather seen as a danger to the freedoms and autonomy of the individual. Keywords: Autonomy, transhumansim, medicine, human enhancement, cognitive enhancement 1.Introduction ”Man, as the subject of knowledge, can transform almost anything into an object of the cognitive act: nature, his corporality, even the laws of his own thinking [...] but there always remains something that is less transparent to investigations” (Manea, T., 2003). -

Professor Julian Savulescu, National Press Club National Australia Bank Address, Wednesday, 8 June, 2005. Randall

Professor Julian Savulescu, National Press Club National Australia Bank Address, Wednesday, 8 June, 2005. Randall: Ladies and Gentlemen, good afternoon, welcome to today’s National Press Club National Australia Bank Address, and a particular welcome to Professor Julian Savulescu, who is our speaker today. Professor Savulescu is Professor of Practical Ethics at the University of Oxford, and he’s also head of a not very well known Melbourne-Oxford stem cell collaboration research, ahhh, which has all sorts of implications for the public policy debate in Australia. He’s also this year’s medallist of the Australian Society of Medical Research. We’ve collaborated with the Society in the past with previous awards of their medals, we’re going to do it again today, and I’d like to invite Professor John Shine, the Chairman of the National Health and Medical Research Council, to actually present that medal to Professor Savulescu. Shine: Thank you, ahh, thank you Ken. The Australian Society for Medical Research each year selects an individual who has an outstanding reputation both nationally and internationally for his or her contributions to medical research, and they’re selected to be the ASMR Medallist. During medical research week, which of course is this week, the ASMR medallist is the guest of honour at functions all throughout Australia, and one of the highlights of course of which is the presentation of the address at the National Press Club. I think it’s important as we hear the Medallist’s address today, to remember the enormous pace of discovery that’s occurring in medical research around the world. -

Human Enhancement Ethics: the State of the Debate

Introduction Human Enhancement Ethics: The State of the Debate Nick Bostrom and Julian Savulescu Background Are we good enough? If not, how may we improve ourselves? Must we restrict ourselves to traditional methods like study and training? Or should we also use science to enhance some of our mental and physical capacities more directly? Over the last decade, human enhancement has grown into a major topic of debate in applied ethics. Interest has been stimulated by advances in the biomedical sciences, advances which to many suggest that it will become increasingly feasible to use medicine and technology to reshape, manipulate, and enhance many aspects of human biology even in healthy individuals. To the extent that such interventions are on the horizon (or already available) there is an obvious practical dimension to these debates. This practical dimension is underscored by an outcrop of think tanks and activist organizations devoted to the biopolitics of enhancement. Already one can detect a biopolitical fault line developing between pro- enhancement and anti-enhancement groupings: transhumanists on one side, who believe that a wide range of enhancements should be developed and that people should be free to use them to transform themselves in quite radical ways; and bioconservatives on the other, who believe that we should not substantially alter human biology or the human condition.¹ There are also miscellaneous groups who try to position themselves in ¹ See e.g. Bostrom, N. 2006. ‘A Short History of Transhumanist Thought’, Analysis and Metaphysics, 5: 63–95 (http://www.nickbostrom.com/papers/history.pdf). 2 between these poles, as the golden mean. -

Procreative Beneficence: Why We Should Select the Best Children

Bioethics ISSN 0269-9702 Volume 15 Number 5/6 2001 PROCREATIVE BENEFICENCE: WHY WE SHOULD SELECT THE BEST CHILDREN JULIAN SAVULESCU ABSTRACT Eugenic selection of embryos is now possible by employing in vitro fertilization (IVF) and preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD). While PGD is currently being employed for the purposes of detecting chromosomal abnormalities or inherited genetic abnormalities, it could in principle be used to test any genetic trait such as hair colour or eye colour. Genetic research is rapidly progressing into the genetic basis of complex traits like intelligence and a gene has been identified for criminal behaviour in one family. Once the decision to have IVF is made, PGD has few `costs' to couples, and people would be more inclined to use it to select less serious medical traits, such as a lower risk of developing Alzheimer Disease, or even for non-medical traits. PGD has already been used to select embryos of a desired gender in the absence of any history of sex-linked genetic disease. I will argue that: (1) some non-disease genes affect the likelihood of us leading the best life; (2) we have a reason to use information which is available about such genes in our reproductive decision-making; (3) couples should select embryos or fetuses which are most likely to have the best life, based on available genetic information, including information about non-disease genes. I will also argue that we should allow selection for non-disease genes even if this maintains or increases social inequality. I will focus on genes for intelligence and sex selection.