University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Movies That Will Get You in the Holiday Spirit

Act of Violence 556 Crime Drama A Adriana Trigiani’s Very Valentine crippled World War II veteran stalks a Romance A woman tries to save her contractor whose prison-camp betrayal family’s wedding shoe business that is caused a massacre. Van Heflin, Robert teetering on the brink of financial col- Alfred Molina, Jason Isaacs. (1:50) ’11 Ryan, Janet Leigh, Mary Astor. (NR, 1:22) lapse. Kelen Coleman, Jacqueline Bisset, 9 A EPIX2 381 Feb. 8 2:20p, EPIXHIT 382 ’49 TCM 132 Feb. 9 10:30a Liam McIntyre, Paolo Bernardini. (2:00) 56 ’19 LIFE 108 Feb. 14 10a Abducted Action A war hero Feb. 15 9a Action Point Comedy D.C. is the takes matters into his own hands About a Boy 555 Comedy-Drama An crackpot owner of a low-rent amusement Adventures in Love & Babysitting A park where the rides are designed with Romance-Comedy Forced to baby- when a kidnapper snatches his irresponsible playboy becomes emotion- minimum safety for maximum fun. When a sit with her college nemesis, a young young daughter during a home invasion. ally attached to a woman’s 12-year-old corporate mega-park opens nearby, D.C. woman starts to see the man in a new Scout Taylor-Compton, Daniel Joseph, son. Hugh Grant, Toni Collette, Rachel Weisz, Nicholas Hoult. (PG-13, 1:40) ’02 and his loony crew of misfits must pull light. Tammin Sursok, Travis Van Winkle, Michael Urie, Najarra Townsend. (NR, out all the stops to try and save the day. Tiffany Hines, Stephen Boss. (2:00) ’15 1:50) ’20 SHOX-E 322 Feb. -

An Assessment of the Development of the Female in Commercial Science Fiction Film

An Assessment of the Development of the Female in Commercial Science Fiction Film being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of PhD in the University of Hull by Dean Turner (BA Hons) October 1998 To SJD Contents Acknowledgements iv Text Note v Introduction 1 PART ONE Chapter l 19 Gender Positioning: The Traditional Science Fiction Film Chapter 2 78 Ideology: The Commercial Science Fiction Film PART TWO Chapter 3 148 Mutation: 1970s Developments Chapter 4 195 Patriarchal Pendulum: Polarised Development of the Female Character Chapter 5 229 Patriarchal Crucible: Composite Development of the Female Character Chapter 6 265 Inverting and Subverting Patriarchy Chapter 7 311 Competition with Patriarchy Conclusion 347 Literature Cited 372 Films Cited 391 Science Fiction Films 393 Non Science Fiction Films 410 Hi Acknowledgements Support during the research and writing of this thesis has been generous and manifold, material and moral. As it would ultimately be too restrictive to aim to enumerate the specific help offered by individuals, I would like simply to offer my sincere gratitude to each of the following for their invaluable patience and assistance: My Supervisors, John Harris and Keith Peacock; and to My Family, Tim Bayliss, Jean and John Britton, A1 Childs, Anita De, Sarah-Jane Dickenson, Craig Dundas-Grant, Jacquie Hanham, Harry Harris, Tim Hatcher, Audrey Hickey, Anaick Humbert, Nike Imoru, Abigail Jackson, Irene Jackson, David Jefferies, Roy Kemp, Bob Leake, Gareth Magowan, Makiko Mikami, Zoie Miller, Barbara Newby, Isobel Nixon, Patricia Pilgrim, Paul Richards, David Sibley Ruth Stuckey, Lesley Tucker, Gail Vickers, Susan Walton, Debbie Waters, Graham Watson, and Rowlie Wymer; and to The Staff and Students of Hull High School, The British Film Institute, and The British Library. -

Ed 063 761 Institution Spons Agency Pub Date Note

4 DOCUMENT RESUME ED 063 761 EM 009 940 TITLE Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Communications of the Committee on Commerce, United States Senate, Ninety-Second Congress, Sec;ond Session on the Surgeon General's Report by the Scientific Advisory Committee on Television and Social Behavior. INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington, D.C. Senate Committ on Commerce. SPONS AGENCY Surgeon General's Scientific Advisory Committee on Television and Social Behavior, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE Apr 7? NOTE 309p.; See also ED 057 595, ED 059 623 through 059 627; EM 009 729 through EM 009 737 AVAILABLE FROMSuperintendent of Documents* U. S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C. 20402 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$13.16 DESCRIPTORS *Aggression; *Children; Federal Legislation; Government Publications; Programing (Broadcast); *Social Behavior; *lelevision; Television Research; Television Viewing; *Violence IDENTIFIERS Federal Communications Commissicn; *Surgeon Generals Report Television Social Behav' ABSTRACT Dnring March 1972 the Subcomn!,-ree on Communications of the Committee on Commerce of the U.S. Senate held hearings on the Surgeon General's Report by the Scientific Advitif:,-y Committee .711 Television and Social sehavior. The complete tele. LI those hearingr is presented here. Included in those who testifid before the committee were the Surgeon General, Dr. Jesse steixfi,r4d, some of the members of the Advisory Committee* r.apresentatives t:elevision networks and protessional associations, and members if citizens' groups. Numerous additional -

Other Areas Clearing David Abnomi Jsm Chairman, Tuesday Present Man; Mrs

T- / /V ,' > FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 2S, 1966 jjPAGE THIRTY-SIX Average Daily Net P r ^ Run The W eather For the Week Ended Airman l.C. Douglas A. Clearing this aftenwXRirWill ^ Can* for Plewort.^ November 19, I960 .' About Town Bird, son o f Mr. and Mrs. R. L ChurQh^lans near 56; fair, cooler tobiglM;, Bird of 38 Harvard Rd., has TMok of Tho*, low near 30; increasing cloudi- ^ j, Francta Blaury^ and Edward recently returned home after Choridf Event ness toinorrow, high In dtolmore of FSall Rlv«r. Masa., completipg his second tour o f 15,131 Vre weokend guosta o f Mr. and duty with the U.S. Airforce in ParkbUI-Joyce Manch6»te^— A CUy of tillage Cham • David ^Imond, director of. mu- ' JMrs. Potar Plynn of 17 Roae- Viet Na3n. He served in the Air unary PI. Police on perimeter deitense at sic at Concordia Lutheran HANdHESTER, CONN. SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 26, 1966 (OlaMtfled Advertitfng oU Fsge 11) .PRICE SEVEN CBNT9; ^ • Flower Shop VOL. LXHtVI, NO. 48 ( f o u r I ^ e n p a g e s —t v SECnON) Phan Rang. x oiu i^h , will conduct the Ooheor- Frank Oakeler; Ftoprietor __' I David C. Keiin, son o f Mr. dia Choir Sunday at 8 p.m. in a SOL MAIN ST., MANOHESim >nd Mrs. W. David Keith o f 66 Manchester lyorid War Bar choral vesper profram, “ Abend- (Neort to Hartford Nattonal niUcrest Rd., has made the sec- racks and Auxiliary will Install muslk IV ." The event is oneh to' Bank) Jond honor roll; and Robert A'. -

Completeandleft

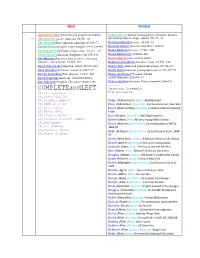

MEN WOMEN 1. David Archuleta=American pop singer=126,384=16 Debbie Allen=Actress, choreographer, television director, DA Desi Arnaz+Jr.=actor, musician=66,903=43 television producer, singer, dancer=55,373=73 Desi Arnaz=Cuban-American musician=47,841=71 Diahnne Abbott=Actress=50,300=83 Damon Albarn=English singer-songwriter=39,325=82 Danneel Ackles=Actress, model=167,304=23 David Allan+Coe=Country music artist=18,337=167 Dawn Addams=Actress=17,552=200 Dallas Austin=American, Songwriter=20,345=156 Diane Addonizio= =24,068=162 Dan Abrams=American lawyer, writer, television Dianna Agron=Actress=438,083=5 executive, entrepreneur=16,488=181 Deborah Ann+Woll=American ctress=18,977=188 David Alan+Grier=American, Actor=14,533=203 Devon Aoki=American model and actress=85,724=47 Dave Annable=American, Actor=29,658=117 Danni Ashe=American pornographic actress=57,289=71 Darren Aronofsky=Film director=13,016=222 Dasha Astafieva=Ukrainian, Model David Arquette=American actor=50,310=67 (Adult/Glamour)=224,488=17 Dan Aykroyd=Canadian film actor=10,041=283 Denise Austin=American, Fitness Guru=30,200=131 ……………. COMPLETEandLEFT Deadstar Assembly DA,Dan Aykroyd Die Antwoord DA,Danny Aiello DA,Darrell Abbott Diego ,Abatantuono ,Actor ,Mediterraneo DA,Debbie Allen Dave ,Abbruzzese ,Drummer ,Former drummer, Pearl Jam DA,Desi Arnaz David ,Abercrombie ,Business ,Founder of Abercrombie & DA,Devon Aoki Fitch DA,Dianna Agron Dan ,Abrams ,Journalist ,NBC legal reporter DA,Dimebag Darrell Abbott Dannie ,Abse ,Poet ,Ash on a Young Man's Sleeve DA,Don Adams David ,Abshire -

Jyiobjl Mobil 79< 18T $ Ladap Israel, Syria Won't Go Along with Saudi Plan

■n - MANCHESTER HERALD. Friday. Feb. 17. 198j Sen. Gary Hart Maldment’s motto: ) '.."j' Manchester FREE FREE FREE has fresh Ideas keep ’em In Scouting beats Fermi • Armorali A WD-40 sample* ... page 2 ... page 13 1 ... page 8 • Fram-Autoiite Car Care Guide* • Kendall Oil Change Guides • Balloons for the kid* • Come see the Factory Reps.i • Special events and prizes WIN WIN WIN A trip for two to Continued cloudy, Manchester, Conn. Chance of showers C e \ ® FREEPORT GRAND BAHAMAS Saturday, Feb. 18, 1984 — See page 2 Single copy: 25<S from ADAP® & Mobil® and A Motorsport Mlnl-Car from ADAP® and Castro! {Entry forms & details in store) A A t . " FRAM Israel, Syria xcV' FILTER w o n ’t g o along : e \ e t o t ® with Saudi plan V \ y M o b il BEIRUT, Lebanon (UPI) — Presi mountaihs and only 3 miles from the Regular 4.99 to 17.99 dent Amin Gemayel agreed under palace. rebel pressure Friday to a peace plan The peace plan provides for the U nheard of savin gs! ^ AIR FILTERS that cancels the Israeli-Lebanese cancellation of the May 17 U.S- Every number In slocKI troop-withdrawal accord but needs the mediated accord between Lebanon and Save over $5.00 a case! unlikely support of Israel and Syria to Israel, which calls for normalization of Saves Gas succeed. relations in exchange of the withdrawal /lutDiite. $1.50 of Israeli troops from Lebanon. The Syria and Israel, both with veto agreement was conditional on the power over the plan, expressed simultaneous withdrawal of Syrian SPARK PLUGS opposition. -

On Television the Television Index

r ON TELEVISION INCLUDING NOVEMBER 19-25, 1956 THE TELEVISION INDEX VOLUME 8 NUMBER 47 PRODUCTION PROGRAMMING TALENT EDITOR: Jerry Leichter 551 Fifth Avenue New York 17 MUrray Hill 2-5910 PUBLISHED BY TELEVISION INDEX, INC. WEEKLY REPORT A FACTUAL RECORD OF THIS WEEK'S EVENTS IN TELEVISION PROGRAMMING THIS WEEK -- NETWORK DEBUTS & HIGFUGHTS Monday(19) CBS- 9-10pm EST; SPECIAL - Our Mr. Sun - FILM (COLOR) from WCBS-TV(NY), 130 sta- tions net, 30 delayed.--3--Spomor- American Telephone & Telegraph Co (Bell System) thru N, W. Ay P-14 Son, (Philo). § Pkgr- American Telephone & Tele- graph Co; Prod & Dir- Frank Capra; Animation sequences by UPA; other production information not available. § S ry-line documentary showing how man has learn- ed scientific facts about the sun and what use he has made of this knowledge, using four characters in the story, two human and two cartoon. Eddie Albert plays a fiction writer and Dr. Frank Baxter plays the part of a scientist. Spec- ial films taken by leading observatories are integrated in the program. The program preempts Studio One, one time only. Wednesday(21) ABC- 7-7:30pm EST; SPECIAL - Bamberger's Thanksgiving Eve Parade of Light- LIVE via remote to WAHC-TV(UY), no. of stations indefinite. § Sponsor- General Electric Co (Housewares & Radio Receivers Div) thru Young & Rubicam, Inc(NY). Pkgr- ABC News & Special Events with Bamberger's Dept Store; Prod- Don Coe; Dir- Marshall Diskin. § John Daly will describe the annual. Bomberger parade from Weequahic Park, Newark, N. J,Robert McCorkle, display director of the de- partment store is in charge of the pageant's creation, which is built around story book characters. -

1950'S TV SHOWS TRIVIA QUESTIONS

1950's TV SHOWS TRIVIA QUESTIONS ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> On the TV sitcom "The Honeymooners", what was the name of Ralph's bowling team? a. The Hurricanes b. The Gladiators c. The Alley Cats d. Pinheads 2> Who played Walter Denton in "Our Miss Brooks"? a. Richard Todd b. Steve McQueen c. Richard Crenna d. Charles Farrell 3> What was Joe Friday's badge number on the crime drama TV series "Dragnet"? a. 701 b. 710 c. 714 d. 705 4> Who was the host of the original TV game show "Concentration"? a. Alan Ludden b. David Frost c. Pat Sajak d. Hugh Downs 5> Airing for 203 episodes, what TV show featured Robert Young as Tim Warren, head of the Warren Family? a. Father Knows Best b. Amos 'n' Andy c. Leave It to Beaver d. Maverick 6> Who played the title role in "Man Against Crime"? a. Robert Montgomery b. Richard Crenna c. Roscoe Kearns d. Ralph Bellamy 7> What is the name of the actor who portrayed little Ricky on the TV comedy series "I Love Lucy"? a. Richard Keith b. William Frawley c. Keith Richardson d. Keith Black 8> Who hosted the first version and then co-hosted the American quiz show "You Bet Your Life"? a. Groucho Marx b. Harvey Korman c. Merv Griffin d. George Fenneman 9> When did the "Today" show first premiere on NBC? a. January 14, 1950 b. January 14, 1952 c. January 14, 1955 d. January 14, 1948 10> Who was the host of the American newsmagazine and documentary series "See it Now"? a. -

Open Megan Ohara Honors Thesis

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF FILM-VIDEO AND MEDIA STUDIES HAS CLASSIC TV GONE OUT OF STYLE? MEGAN KATHLEEN O‘HARA Spring 2011 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Finance with honors in Media Studies Reviewed and approved* by the following: Jeanne Lynn Hall Associate Professor of Communications Thesis Supervisor and Honors Adviser Matthew P. McAllister Professor of Communications Faculty Reader * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT From The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, The Donna Reed Show, and Leave It to Beaver to Roseanne, Everybody Loves Raymond, and Married…with Children, the television and its sitcom families have been a part of our lives from TV's inception. Although sixty years have passed since TV's modest beginnings, through the power of technology, reruns, and networks such as TV Land, we, the modern viewing public, have a glimpse into the world of classic TV. A world filmed entirely in black and white, it gives us insight into the TV world of yesteryear. It also gives us the chance to compare that world with today's world filmed in spectacular Technicolor. It's easy to see that black and white versus color isn't the only difference between classic TV and modern programming. Turn on the TV during primetime tonight. Notice anything? Look in the upper left hand corner of the screen. Most shows today come with a rating, warning parents of violence, language, sex, and drugs that may deem the program unsuitable for younger viewers. -

To Download The

FREE EXAM Complete Physical Exam Included New Clients Only Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined Wellness Plans Extended Hours Multiple Locations www.forevervets.com4 x 2” ad YourYour Community Community Voice Voice for 50 for Years 50 Years RRecorecorPONTE VEDVEDRARA dderer entertainment EEXTRATRA! ! Featuring TV listings, streaming information, sports schedules,X puzzles and more! February 18 - 24, 2021 Sample sale: Offering: 1/2 off INSIDE: • Hydrafacials Venus Legacy The latest Treatments • BOTOX Call for House & Home • DYSPORT details listings • RF Microneedling Page 21 • Body Contouring • B12 Complex • Lipolean Injections • Colorscience Products • Alastin Skincare Get Skinny with it! (904) 999-0977 The CW clears the runway for a new Superman and Lois Lane www.SkinnyJax.comwww.SkinnyJax.com 1361 13th Ave., Ste. 140 Elizabeth Tulloch and Tyler Hoechlin star in “Superman & Lois,” premiering Tuesday on The CW. Jacksonville Beach1 x 5” ad Now is a great time to It will provide your home: ListEvery Your Home House for Sale Has• Complimentary a Story coverage while … Kathleen Floryan the home is listed Broker Associate Introducing a new way to market• An& edgesell inyour the local home, market LISTexclusively provided IT by a Storybook,because distinctive buyers prefer to to purchaseyour home. a [email protected] home that a seller stands behind • Reduced post-sale liability with 904-687-5146 A Storybook is an exciting, interactive,® digital presentation WITH ME! ListSecure like nothing you’ve seen, but pulls everything together in https://www.kathleenfloryan.exprealty.com BK3167010 oneI willspace provide for buyers you a to FREE view a story about your home. -

ALTERATION For

'I J* f . V FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER SO. ISOOT FA<SE T W B N 'll iEanrli^ator jEo^nfng l|rntlb Public Health Affsociatian Seeks Your )ort During October AboutTown Crashes Involve ATcrase Daily Net Press Run The Westher Ttm Fellowship Men’s I^escue of: F«r tlw WMk Ended Foreeaet of D. 8. Weotber Bmme the SalTstlon A m y will men 8st^ Seven Vehicles 8«t. M. leee urday at 7:15 p.m. at the church. Sanog thil ofteraooB ood eool- After a btuiness meetipr, refresh 13,220 er thaiB yeeterdag. Clear and eoM- ments will be sreved.' There were no injuries or ar er tonlgkt with froot la the ae>'> rests resulting from three sepa Member • ( the A udit. mally cold Interior vaUeya. T o UST DAY morrow moetly fair. T>inm^flve members attended rate accidents late yesterday af Betfean of Obeokuion ■ Manchester— City of rUlage Charm the first fall meeting and potluck ternoon and evening in which sev of Jayoee Wives Wednesday eve- .lUhg at Center Congregational en vehicles were Involved. (CUaellled Advertlsmg on Page 17) PRICE FIVE CENTS Church. Atty. Vlnoent Diana, Jay- Shortly before 5 p.m., a four-car VOL. LXXX, NO. 1 (FOURTEEN PAGES—TV SECTION) MANCHESTER, CONN., SATURDAY, OCTOBER 1. 1960 oee jnesldent, asked the women to rear end collision occurred on help stimulate Interest In Jaycee Center St. weit of Olcott St. It in activities, and expressed appreda volved cars driven by Gerald N. tion for past services. Mrs. Eldred Cornier, 34, of Rose Lane, An Couch presented a demonstration dover: Elisabeth F. -

Extraordinary Circumstances

FINAL-1 Sat, Mar 28, 2020 4:34:14 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of April 5 - 11, 2020 Extraordinary circumstances Jonah Hauer-King in “World on Fire” INSIDE •Sports highlights Page 2 •TV Word Search Page 2 •Family Favorites Page 4 •Hollywood Q&A Page14 The latest offering from the PBS Masterpiece collection, “World on Fire,” is set during the days leading up to World War II and features the stories of everyday people whose fates are intertwined in a world on the brink of war. Premiering Sunday, April 5, on PBS, the series stars Jonah Hauer-King (“Little Women”), Sean Bean (“Game of Thrones”), Helen Hunt (“Mad About You”), Kasia Tomaszeski (Zofia Wichłacz, “1983”) and more. WANTED MOTORCYCLES, SNOWMOBILES, OR ATVS GOLD/DIAMONDS ✦ 40 years in business; A+ rating with the BBB. ✦ For the record, there is only one authentic CASH FOR GOLD, Bay 4 Group Page Shell PARTS & ACCESSORIES We Need: SALESMotorsports & SERVICE 5 x 3” Gold • Silver • Coins • Diamonds MASS. MOTORCYCLEWANTED1 x 3” We are the ORIGINAL and only AUTHENTIC SELLBUYTRADEINSPECTIONS GROW CASH FOR GOLD Spring Sales! on the Methuen line, above Enterprise Rent-A-Car at 527 So. Broadway, Rte. 28, Salem, NH • 603-898-2580 1615 SHAWSHEEN ST., TEWKSBURY, MA CALL (978)946-2000 TO ADVERTISE PRINT • DIGITAL • MAGAZINE • DIRECT MAIL Open 7 Days A Week ~ www.cashforgoldinc.com 978-851-3777 WWW.BAY4MS.COM FINAL-1 Sat, Mar 28, 2020 4:34:15 PM COMCAST ADELPHIA 2 Stars on screen Kingston CHANNEL Atkinson Goodbye, ‘Schitt’s Creek’: Cult hit bids farewell in 90-minute TV event Salem Londonderry Sandown Windham Pelham, By Michelle Rose ratings steadily climbed then Crime”).