Heat Index and Wind Chill Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Winter Forecasting Handbook Winter Storm Information That Is Useful to the Public

A Winter Forecasting Handbook Winter storm information that is useful to the public: 1) The time of onset of dangerous winter weather conditions 2) The time that dangerous winter weather conditions will abate 3) The type of winter weather to be expected: a) Snow b) Sleet c) Freezing rain d) Transitions between these three 7) The intensity of the precipitation 8) The total amount of precipitation that will accumulate 9) The temperatures during the storm (particularly if they are dangerously low) 7) The winds and wind chill temperature (particularly if winds cause blizzard conditions where visibility is reduced). 8) The uncertainty in the forecast. Some problems facing meteorologists: Winter precipitation occurs on the mesoscale The type and intensity of winter precipitation varies over short distances. Forecast products are not well tailored to winter Subtle features, such as variations in the wet bulb temperature, orography, urban heat islands, warm layers aloft, dry layers, small variations in cyclone track, surface temperature, and others all can influence the severity and character of a winter storm event. FORECASTING WINTER WEATHER Important factors: 1. Forcing a) Frontal forcing (at surface and aloft) b) Jetstream forcing c) Location where forcing will occur 2. Quantitative precipitation forecasts from models 3. Thermal structure where forcing and precipitation are expected 4. Moisture distribution in region where forcing and precipitation are expected. 5. Consideration of microphysical processes Forecasting winter precipitation in 0-48 hour time range: You must have a good understanding of the current state of the Atmosphere BEFORE you try to forecast a future state! 1. Examine current data to identify positions of cyclones and anticyclones and the location and types of fronts. -

* Corresponding Author Address: Mark A. Tew, National Weather Service, 1325 East-West Highway, Silver Spring, MD 20910; E-Mail: [email protected]

P1.13 IMPLEMENTATION OF A NEW WIND CHILL TEMPERATURE INDEX BY THE NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE Mark A. Tew*1, G. Battel2, C. A. Nelson3 1National Weather Service, Office of Climate, Water and Weather Services, Silver Spring, MD 2Science Application International Corporation, under contract with National Weather Service, Silver Spring, MD 3Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research, Silver Spring, MD 1. INTRODUCTION group is called the Joint Action Group for Temperature Indices (JAG/TI) and is chaired by the NWS. The goal of The Wind Chill Temperature (WCT) is a term used to JAG/TI is to internationally upgrade and standardize the describe the rate of heat loss from the human body due to index for temperature extremes (e.g., Wind Chill Index). the combined effect of wind and low ambient air Standardization of the WCT Index among the temperature. The WCT represents the temperature the meteorological community is important, so that an body feels when it is exposed to the wind and cold. accurate and consistent measure is provided and public Prolonged exposure to low wind chill values can lead to safety is ensured. frostbite and hypothermia. The mission of the National After three workshops, the JAG/TI reached agreement Weather Service (NWS) is to provide forecast and on the development of the new WCT index, discussed a warnings for the protection of life and property, which process for scientific verification of the new formula, and includes the danger associated from extremely cold wind generated implementation plans (Nelson et al. 2001). chill temperatures. JAG/TI agreed to have two recognized wind chill experts, The NWS (1992) and the Meteorological Service of Mr. -

The Relative Contributions of Temperature and Moisture to Heat Stress

1 The Relative Contributions of Temperature and Moisture to Heat Stress 2 Changes Under Warming ∗ 3 Nicholas J. Lutsko 4 Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA ∗ 5 Corresponding author address: Nicholas Lutsko, [email protected] 6 E-mail: [email protected] Generated using v4.3.2 of the AMS LATEX template 1 ABSTRACT 7 Increases in the severity of heat stress extremes are potentially one of the 8 most impactful consequences of climate change, affecting human comfort, 9 productivity, health and mortality in many places on Earth. Heat stress results 10 from a combination of elevated temperature and humidity, but the relative con- 11 tributions each of these makes to heat stress changes have yet to be quantified. 12 Here, conditions on the baseline specific humidity are derived for when spe- 13 cific humidity changes will dominate heat stress changes (as measured using 14 the equivalent potential temperature, qE), and for when temperature changes 15 will dominate. Separate conditions are derived over ocean and over land, in 16 addition to a condition for when relative humidity changes dominate over the 17 temperature response at fixed relative humidity. These conditions are used to 18 interpret the qE responses in transient warming simulations with an ensemble 19 of models participating in the Sixth Climate Model Intercomparison Project. 20 The regional pattern of qE changes is shown to be largely determined by the 21 pattern of specific humidity changes, with the pattern of temperature changes 22 playing a secondary role. This holds whether considering changes in mean 23 summertime qE or in extreme (98th percentile) qE events. -

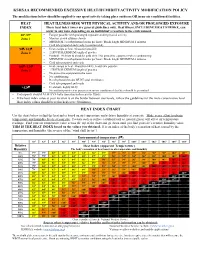

Kshsaa Recommended Excessive Heat/Humidityactivity Modification Policy Heat Index Chart

KSHSAA RECOMMENDED EXCESSIVE HEAT/HUMIDITYACTIVITY MODIFICATION POLICY The modifications below should be applied to any sport/activity taking place outdoors OR in un-air conditioned facilities. HEAT HEAT ILLNESS RISK WITH PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND/OR PROLONGED EXPOSURE INDEX These heat index zones are general guidelines only. Heat illness, INCLUDING HEAT STROKE, can occur in any zone depending on an individual’s reaction to the environment. 80°-89° – Fatigue possible with prolonged exposure and/or physical activity Zone 1 – Monitor at-risk athletes closely – MINIMUM 3 rest/hydration breaks per hour / Break length MINIMUM 4 minutes – Cold tubs prepared and ready (recommended) 90- 103 – Heat cramps or heat exhaustion possible Zone 2 – 2 HOUR MAXIMUM length of practice – Football: Helmets & shoulder pads only / No protective equipment when conditioning – MINIMUM 4 rest/hydration breaks per hour / Break length MINIMUM 4 minutes – Cold tubs prepared and ready 103- 124 – Heat cramps or heat exhaustion likely, heatstroke possible Zone 3 – 1 HOUR MAXIMUM length of practice – No protective equipment to be worn – No conditioning – Rest/hydration breaks MUST total 20 minutes – Cold tubs prepared and ready >124 – Heatstroke highly likely – No outdoor practices or practices in un-air conditioned facilities should be permitted – Participants should ALWAYS have unrestricted access to fluids. – If the heat index value at your location is on the border between two levels, follow the guidelines for the more conservative level. – Heat index values should be rechecked every 30 minutes. HEAT INDEX CHART Use the chart below to find the heat index based on air temperature and relative humidity at your site. -

Yeah, There Is a Difference Measuring Road Weather and Using It!

Yeah, There is a Difference Measuring Road Weather and Using it! Jon Tarleton Head of Transportation Marketing – Meteorologist Twitter: @jontarleton What are we going to talk about? . The weather of course! But when and what matters! . The weather before, during, and after a storm. The weather around frost. Let’s start with nothing and build on it. When we are done you will know what information is good information! Page 2 © Vaisala 10/20/2016 [Name] There is weather… And then there is road weather… Page 3 © Vaisala 10/20/2016 [Name] Let’s start at the beginning! Page 4 © Vaisala 10/20/2016 [Name] You just got your fleet of new plows! Page 5 © Vaisala 10/20/2016 [Name] But otherwise you are Anytown, USA Page 6 © Vaisala 10/20/2016 [Name] Approaching winter storm Page 7 © Vaisala 10/20/2016 [Name] Air temperature .Critical in telling us the type of precipitation. .How do we measure it? .Measured from 6ft off the ground .In a white vented enclosure .Combined with wind it has an impact on our road surface. Page 8 © Vaisala 10/20/2016 [Name] Thermodynamics 101 .To understand how the air impacts our pavement we must understand how heat transfers from objects, and between the air and objects. Sun Air Subgrade Page 9 © Vaisala 10/20/2016 [Name] Wind Page 10 © Vaisala 10/20/2016 [Name] Wind – An important piece of the weather . Lows typical move from southwest to northwest. System may not always contain all of the precipitation types. Best snow is usually approx. L 250 miles north of center of low. -

Weather Elements

In this chapter Temperature Humidity Clouds Precipitation WEATHER ELEMENTS TEMPERATURE per cent of the incoming radiation. The more energy a surface absorbs, the more heat it will eventually release Heat is one form of energy. The sun radiates energy in back into the atmosphere. waves, in this case short waves, to the earth. The atmosphere does not absorb short-wave energy readily. The clouds, dust and water vapour in the atmosphere To show your students that the rate at which energy is absorbed depends on the colour of a deflect about half of the sun's energy back into space. material, try Activity number 7 on page 8-9 in What passes through is absorbed by the land and water the Activity Section. and converted to heat. The earth radiates this back as Eventually, all the energy the sun radiates to earth long-wave energy, which then warms the air above. In returns to outer space creating the global balance of short, the earth acts as a radiator, which you probably energy. This prevents the earth from heating up or know already, if you have ever walked down a long stretch cooling down. of sidewalk or across a large parking lot on a hot day and watched (or felt) the heat rise from the pavement. The temperature on your thermometer this morning, however, was probably affected more by the season, the Several factors affect how much of the sun's energy a time of day, the latitude, and the geography of your area surface, such as a field, absorbs. One is its colour. -

NOTES and CORRESPONDENCE the Steadman Wind Chill

DECEMBER 1998 NOTES AND CORRESPONDENCE 1187 NOTES AND CORRESPONDENCE The Steadman Wind Chill: An Improvement over Present Scales ROBERT G. QUAYLE National Climatic Data Center, Asheville, North Carolina ROBERT G. STEADMAN School of Agricultural Science, La Trobe University, Bundoora, Victoria, Australia 19 February 1998 and 24 June 1998 ABSTRACT Because of shortcomings in the current wind chill formulation, which did not consider the metabolic heat generation of the human body, a new formula is proposed for operational implementation. This formula, referred to as the Steadman wind chill, is based on peer-reviewed research including a heat generation and exchange model of an appropriately dressed person for a range of low temperatures and wind speeds. The Steadman wind chill produces more realistic wind chill equivalents than the current NWS formulation. It is easy to determine from tables (calculated by application of a quadratic ®t in both U.S. and metric units) with values accurate to within 18C. 1. Introduction freezing water to actually freeze under various wind and temperature conditions rather than any human physio- Many scientists have noted de®ciencies in the current logical model of heat loss and gain under equivalent wind chill scale (e.g., Court 1992; Dixon and Prior 1987; conditions. The major consequence is that water, not Driscoll 1985, 1992, 1994; Kessler 1993, 1994, 1995; having a metabolic heat source and not being appro- Horstmeyer 1994; Osczevski 1995; Schwerdt 1995; priately attired in human clothing, produces colder wind Steadman 1995). There was a session partly devoted to chills (for given wind and temperature conditions) than this topic at the 22d Annual Workshop on Hazards Re- those experienced by live, clothed humans. -

Martian Windchill in Terrestrial Terms Randall Osczevski

MARTIAN WINDCHILL IN TERRESTRIAL TERMS RANDALL OSCZEVSKI A two-planet model of windchill suggests that the weather on Mars is not nearly as cold as it sounds. he groundbreaking book The Case for Mars (Zubrin 1996) advocates human exploration and colonization of the red planet. One of its themes is that Mars is beset by dragons of the sort T that ancient mapmakers used to draw on maps in unexplored areas. The dragons of Mars are daunting logistical and safety challenges that deter human exploration. One such dragon must surely be its weather, for Mars sounds far too cold for human life. No place on Earth experiences the low temperatures that occur every night on Mars, where even in the tropics in summer the thermometer often reads close to –90°C and, in midlatitudes in winter, as low as –120°C. The mean annual temperature of Mars is –63°C (Tillman 2009) com- pared to +14°C on Earth (NASA 2010). We can only try to imagine how cold the abysmally low temperatures of Mars might feel, especially when combined with high speed winds Left: The High Arctic feels at least as cold as Mars, year round (Photo by R. Osczevski 1989). Right: Twin Peaks of Mars. (Photo by NASA, Pathfinder Mission 1997) AMERICAN METEOROLOGICAL SOCIETY APRIL 2014 | 533 Unauthenticated | Downloaded 09/30/21 08:37 PM UTC that sometimes scour the planet. This intensely bone- refer to the steady state heat transfer from the upwind chilling image of Mars could become a psychological sides of internally heated vertical cylinders having the barrier to potential colonists, as well as to public same diameter, internal thermal resistance, and core support for such ventures. -

Wet Bulb Globe Temperature Faqs

3/30/17 3rd Annual Collaborative Solutions for Safety in Sport National Meeting Wet Bulb Globe Temperature FAQs Environmental Monitoring Indices • Wet bulb globe temperature (WBGT) • Air temperature • Relative humidity • Sling psychrometer • Heat index • OSHA chart 1 3/30/17 How are they different? Wet Bulb Globe Temperature • Invented in 1950s for the US Army and Marine Corps • Wet Bulb Temperature (Tw) • Humidity, (Wind) • Globe Temperature (Tg) • Solar radiation, (Wind) • Dry Bulb Temperature (Td) • Air temperature WBGT= 0.7Tw + 0.2Tg + 0.1Td Budd GM. Wet-bulb globe temperature (WBGT)--its history and its limitations. J Sci Med Sport Sports Med Aust. 2008;11(1):20-32. How are they different? Sling Psychrometer • Two thermometers mounted together in the same device. • Calculates the difference between: • Ambient temperature • Wet-bulb thermometer $50- $100/unit • Measures relative humidity • Allows clinician to then derive heat index 2 3/30/17 How are they different? Heat Index • Heat Index is how hot it feels when relative humidity is factored into the ambient temperature. • Heat Index is created based on shady, light-wind conditions. • Not full sunshine • Not strong-wind • Number may NOT be reliable under extreme heat conditions How are they different? Heat Index • Assumptions of Heat Index • Shaded Football helmet • (full sun can increase Heat Index by 15oF) • 5’7”, 147 lbs • Long pants and short sleeve shirtFootball uniform • Walking at 3 mph High physical demand 3 3/30/17 Why WBGT? • WBGT is a more comprehensive representation of environmental conditions • Solar radiation & wind speed are factored into the equation • Devised to account for physical activity Regional Specificity • Regional specific guideline by Grundstein et al. -

Heat Index Climatology for the North-Central United States

HEAT INDEX CLIMATOLOGY FOR THE NORTH-CENTRAL UNITED STATES Todd Rieck National Weather Service La Crosse, Wisconsin 1. Introduction middle Mississippi River Valleys, and the western Great Lakes. Also, the physiological Heat is an underrated danger, with an response to heat will be briefly investigated, average of 175 Americans losing their lives including a review of how heat acclimatization annually from heat-related causes. According to affects the human body’s biology. This the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, protective biological response is an important from 1979-2003 excessive heat exposure consideration when evaluating the impact of the caused 8,015 deaths in the United States. heat on those that are, or are not, acclimatized During this period, more people died from to the heat. extreme heat than from hurricanes, lightning, tornadoes, and floods combined. In this study, 95°F will be used as the start for the climatological analysis as prolonged Heat kills by taxing the human body beyond exposure to heat this warm increases the risk of its ability to cool itself. Cooling is primarily sunstroke, heat cramps, and heat exhaustion accomplished by the evaporation of perspiration. (Table 1) . How efficiently this process functions is directly related to the amount of water vapor in the air. 2. Data High moisture content reduces the evaporative cooling rate of perspiration, making it difficult for All available weather observations from the the body to maintain a steady and safe internal National Climatic Data Center were used from temperature. One way to measure the 192 locations (Fig. 1), extending from Utah to combined effect of temperature and moisture on Michigan, and from the Canadian-U.S. -

Appendix a Gempak Parameters

GEMPAK Parameters APPENDIX A GEMPAK PARAMETERS This appendix contains a list of the GEMPAK parameters. Algorithms used in computing these parameters are also included. The following constants are used in the computations: KAPPA = Poisson's constant = 2 / 7 G = Gravitational constant = 9.80616 m/sec/sec GAMUSD = Standard atmospheric lapse rate = 6.5 K/km RDGAS = Gas constant for dry air = 287.04 J/K/kg PI = Circumference / diameter = 3.14159265 References for some of the algorithms: Bolton, D., 1980: The computation of equivalent potential temperature., Monthly Weather Review, 108, pp 1046-1053. Miller, R.C., 1972: Notes on Severe Storm Forecasting Procedures of the Air Force Global Weather Central, AWS Tech. Report 200. Wallace, J.M., P.V. Hobbs, 1977: Atmospheric Science, Academic Press, 467 pp. TEMPERATURE PARAMETERS TMPC - Temperature in Celsius TMPF - Temperature in Fahrenheit TMPK - Temperature in Kelvin STHA - Surface potential temperature in Kelvin STHK - Surface potential temperature in Kelvin N-AWIPS 5.6.L User’s Guide A-1 October 2003 GEMPAK Parameters STHC - Surface potential temperature in Celsius STHE - Surface equivalent potential temperature in Kelvin STHS - Surface saturation equivalent pot. temperature in Kelvin THTA - Potential temperature in Kelvin THTK - Potential temperature in Kelvin THTC - Potential temperature in Celsius THTE - Equivalent potential temperature in Kelvin THTS - Saturation equivalent pot. temperature in Kelvin TVRK - Virtual temperature in Kelvin TVRC - Virtual temperature in Celsius TVRF - Virtual -

The Heat Index "Equation" (Or, More Than You Ever Wanted to Know About Heat Index)

SR 90-23 Technical Attachment 7/1/90 The Heat Index "Equation" (or, More Than You Ever Wanted to Know About Heat Index) Lans P. Rothfusz Scientific Services Division NWS Southern Region Headquarters, Fort Worth, TX Now that summer has spread its oppressive ridge over most of the Southern Region, NWS phones are ringing off their hooks with questions about the Heat Index. Many questions regard the actual equation used in calculating the Heat Index. Some callers are satisfied with the response that it is extremely complicated. Some are satisfied with the nomogram (see Attachment 1). But there are a few who will settle for nothing less than the equation itself. No true equation for the Heat Index exists. Heat Index values are derived from a collection of equations that comprise a model. This Technical Attachment presents an equation that approximates the Heat Index and, thus, should satisfy the latter group of callers. The Heat Index (or apparent temperature) is the result of extensive biometeorological studies. The parameters involved in its calculation are shown below (from Steadman, 1979). Each of these parameters can be described by an equation but they are given assumed magnitudes (in parentheses) in order to simplify the model. # Vapor pressure. Ambient vapor pressure of the atmosphere. (1.6 kPa) # Dimensions of a human. Determines the skin's surface area. (5' 7" tall, 147 pounds) # Effective radiation area of skin. A ratio that depends upon skin surface area. (0.80) # Significant diameter of a human. Based on the body's volume and density. (15.3 cm) # Clothing cover.