Speculative Methodologies & Emergent Literacies: Walking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Children's Mathematics

8657pre.qxd 05/07/2006 08:24 Page i Children’s Mathematics 8657pre.qxd 05/07/2006 08:24 Page ii 8657pre.qxd 05/07/2006 08:24 Page iii Children’s Mathematics Making Marks, Making Meaning Second Edition Elizabeth Carruthers and Maulfry Worthington 8657pre.qxd 05/07/2006 08:24 Page iv ᭧ Elizabeth Carruthers and Maulfry Worthington 2006 First published 2006 Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, only with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers. Paul Chapman Publishing A SAGE Publications Company 1 Oliver’s Yard London EC1Y 1SP SAGE Publications Inc 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, California 91320 SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd B-42, Panchsheel Enclave Post Box 4109 New Delhi 110 017 Library of Congress Control Number: 2006923703 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 10 1-4129-2282-8 ISBN 13 978-1-4129-2282-1 ISBN 10 1-4129-2283-6 ISBN 13 978-1-4129-2283-8 (pbk) Typeset by Dorwyn, Wells, Somerset Printed in Great Britain by T.J. International, Padstow, Cornwall Printed on paper from sustainable resources 8657pre.qxd 05/07/2006 08:24 Page v Contents About the Authors ix Acknowledgements -

Acoustic Sounds Catalog Update

WINTER 2013 You spoke … We listened For the last year, many of you have asked us numerous times for high-resolution audio downloads using Direct Stream Digital (DSD). Well, after countless hours of research and development, we’re thrilled to announce our new high-resolution service www.superhirez.com. Acoustic Sounds’ new music download service debuts with a selection of mainstream audiophile music using the most advanced audio technology available…DSD. It’s the same digital technology used to produce SACDs and to our ears, it most closely replicates the analog experience. They’re audio files for audiophiles. Of course, we’ll also offer audio downloads in other high-resolution PCM formats. We all like to listen to music. But when Acoustic Sounds’ customers speak, we really listen. Call The Professionals contact our experts for equipment and software guidance RECOMMENDED EQUIPMENT RECOMMENDED SOFTWARE Windows & Mac Mac Only Chord Electronics Limited Mytek Chordette QuteHD Stereo 192-DSD-DAC Preamp Version Ultra-High Res DAC Mac Only Windows Only Teac Playback Designs UD-501 PCM & DSD USB DAC Music Playback System MPS-5 superhirez.com | acousticsounds.com | 800.716.3553 ACOUSTIC SOUNDS FEATURED STORIES 02 Super HiRez: The Story More big news! 04 Supre HiRez: Featured Digital Audio Thanks to such support from so many great customers, we’ve been able to use this space in our cata- 08 RCA Living Stereo from logs to regularly announce exciting developments. We’re growing – in size and scope – all possible Analogue Productions because of your business. I told you not too long ago about our move from 6,000 square feet to 18,000 10 A Tribute To Clark Williams square feet. -

EDEE 375: Instructional Strategies for Emergent Literacies (01) ECTR 216 (01) Tue/Thur 9:25-10:40 (02)Tues/Thur: 10:50 A.M.-12:05

EDEE 375: Instructional Strategies for Emergent Literacies (01) ECTR 216 (01) Tue/Thur 9:25-10:40 (02)Tues/Thur: 10:50 a.m.-12:05 Instructor: Dr. Jennifer Barrett-Tatum Office: School of Education, 86 Wentworth St, Room 218 Contact information: [email protected] 865-405-8266 (cell-text before calling and during professional hours) 843-953-5821 (office) Please use email as a primary form of contact Office hours: Tuesday: 12:15 p.m.-2:45 p.m. Thursday: 1 to 3:30 p.m. Virtual office hours by appointment (Skype/FaceTime/Phone) M-F Required Readings: Vacca & Vacca (2014) Reading and Learning to Read (9th edition). Pearson. OAKS Readings Required technology: Digital Device (iPad, tablet of any kind, laptop) OAKS (all items receiving a grade must be turned in individually in Oaks) Word Understanding and use of digital applications such as Power Point, imovie, Voice Thread, or MovieMaker. www.kahoot.it.com Poll Everywhere Scope: This course provides a study of the fundamentals of literacy, including reading, writing, listening, speaking, viewing, and designing relevant to learners from Pre-K through 3rd grade. It emphasizes the literacy process, factors affecting that process, and the principles and skills involved in the development of literacy within young children. (NCATE 1, 2b, 3a-e; NAEYC/EC 1, 4, 4a-c & 3; ACEI 2.1) This course is intended to question what you know and to force you to be able to articulate what you learn about RECOMMENDED PRACTICE in literacy instruction. Course Outcomes: All teacher preparation programs in the School of Education (SOEHHP) are guided by a commitment to Making the Teaching Learning Connection through three Elements of Teacher Competency, which are at the heart of the SOEHHP Conceptual Framework: EDEE 375 Spring 2017 Page 2 (1) Understanding and valuing the learner (2) Knowing what and how to teach and assess and how to create an environment in which learning occurs (3) Understanding themselves as professionals. -

Cardinal Washington 0250E 20

© Copyright 2019 Alison Cardinal i How Literacy Flows and Comes to Matter: A Participatory Video Study Alison Cardinal A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2019 Reading Committee: Anis Bawarshi, Chair Emma Rose Juan Guerra Nancy Bou Ayash ii Program Authorized to Offer Degree: English University of Washington Abstract How Literacy Flows and Comes to Matter: A Participatory Video Study Alison Cardinal Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Anis Bawarshi Department of English Using participatory video methods, an intersectional feminist methodology, this dissertation offers a visual portrait of how university students’ literate activity matters and moves. Drawing on the video and audio data 18 university students created over the course of four years, this study investigates how students’ literacies flow as they physically move across the shifting contexts of school, home, community, and work. Through video production, student collaborators showed how they create meaning and connection between and within unstable literate landscapes through their emergent material/discursive practices of writing, reading, communicating, and translating. This study also explores how these literacy flows are regulated iii and valued as they move and how the persons who use them come to matter. In this study, three key findings emerge: 1) Feminist and anti-oppressive research methods, such as participatory video, open up space for participants to negotiate their racial and gendered representations, giving them control over how they matter and what they create matters to the discipline 2) Through the process of filming, literacies emerge as mattering, both in how they materialize and hold personal significance. -

ICT in the Early Years (Learning and Teaching with Information

ITC IN THE EARLY YEARS Mary Hayes and David Whitebread ● How can computers and other ICT applications be most effectively used to support learning in early years settings? ● Why is it important that young children use ICT in ways which are O playful, creative and explorative? ● What research has been carried out about young children using computers and ICT, and what does this tell us? PEN ICT in the Early Years carefully considers the potential of ICT to provide opportunities for young children to learn through playful and creative activities, examining research and practice in relation to the educational uses of ICT with young children. The book raises important issues about teaching in the early years using ICT, such as giving pupils control, co-operative working, access and assessment. U In addition, it: McGraw - HillMcGraw Education ● Recounts recent research evidence ● NIVERSITY Provides practical ideas for early years teachers ● Provokes debate about the future of ICT in early years education The book’s focus is on research outcomes, viewed through discussion of practical classroom approaches, with the pupil viewed as a competent learner and assessor. Emphasis is placed on creative and playful aspects of ICT, with the child as an active agent authoring, experimenting, and creating, rather than passively receiving. ICT in the Early Years is essential reading for teachers and teachers in training, and is also of use to other associated professionals, such as classroom assistants, home educators and nursery teachers. Parents with an interest in the use of technology in education will also find the book of genuine interest. -

K-2 ELA Handout

COSA Common Core State Standards Regional Series “Reading and Writing in the Classroom” A Statewide Regional Series for District and School Leaders of CCSS Elementary (K-2) English Language Arts Session Locations: April 14, 2014 – Eagle Crest Resort, Redmond, OR April 28, 2014 – Linn County Expo Center, Albany, OR May 6, 2014 - Convention Center, Pendleton, OR ELA Presenter: Jon Schuhl, SMc Curriculum, [email protected] Goals of CCSS Reading and Writing in the Classroom . U.S. students will become more competitive with A+ countries. Colleges will have less remediation for incoming students. Students across the country will have standards that are of equal rigor. Allows for development of common Jon Schuhl assessments and teaching materials. SMc Curriculum Spring 2014 The Standards Define: The Standards Do NOT Define: . what is most essential . how teachers should teach . grade level expectations . all that can or should be taught . what students are expected to know and be able . the nature of advanced work to do . intervention methods or materials . cross-disciplinary literacy skills . the full range of supports for English learners . mathematical habits of mind and students with special needs ELA Features ELA Features Reading Writing: Text types, responding to reading, and research . Balance of literature and informational texts . Text complexity and growth of comprehension . Writing arguments/opinions . The reading standards place equal emphasis on . Writing informative/explanatory texts the sophistication of what students read and the . Writing narratives skill with which they read. Strong and growing across-the-curriculum emphasis on students writing arguments and informative/explanatory texts 1 ELA Features ELA Features Language: Conventions (grammar), effective use, Speaking and Listening: Flexible communication and vocabulary and collaboration . -

Postcolonial Approaches to Music in the Space Age

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2019 Listening for the Cosmic Other: Postcolonial Approaches to Music in the Space Age Paige Zalman West Virginia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Zalman, Paige, "Listening for the Cosmic Other: Postcolonial Approaches to Music in the Space Age" (2019). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 3797. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/3797 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Listening for the Cosmic Other: Postcolonial Approaches to Music in the Space Age” Paige Zalman Thesis submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Musicology Travis Stimeling, Ph.D., -

What Do Computer Games Have to Do with Libraries and Learning?

What do computer games have to do with Libraries and learning? How to engage and connect learners of different age groups and with different interests using computer games as the vehicle for learning. Marie O’Brien Manager Library Services ELTHAM College of Education Australia Two teachers have undertaken a project in which year five and six students design computer games and year ten to twelve students build them. The younger students are taught basic flow diagram techniques and thus patterns of logic. They then select a topic of personal interest for their game design. The game is in the form of a quest for the player and must contain material that has been researched using Library resources. The complete, fully documented game designs are passed to the senior Information Technology students who produce them. All students are fully and formally accredited for their work. Introduction Games have been played for as long as human kind has existed and have been used in educational settings for many years as a means of engaging students with learning. In the latter half of the 20th century computer games began to appear in the public arena at a time when advances in technology saw the advent of the microchip, and the subsequent emergence of the personal computer onto the world market. Since then computer programmers have progressed from being generic programmers to working in specialized areas of programming, one of which is gaming. “Since the invention of computers, computer games have been a popular form of entertainment. Children and adults have enjoyed playing computer games and do so now on a massive scale” (Denny). -

Locating the Astronaut Body in Space

Wesleyan University The Honors College Locating the Astronaut Body in Space by Rachel Quinn Fischhoff Class of 2008 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors in Dance and American Studies Middletown, Connecticut April, 2008 Table of Contents Acknowledgments Introduction 1 Chapter 1: The Astronaut Body in Freefall 5 Chapter 2: The Lunar Stage 37 Chapter 3: How to Make Two Dances 59 Conclusion 77 Selected Primary Sources 80 Bibliography 83 Acknowledgements Thank you Rachel Hirsch, Martha Armstrong Gray, Ted Munter and Moses Rifkin for first teaching me to learn all things in all ways. I would like to thank Nicole Stanton for her unwavering support throughout this process, the faculty of the Dance and American Studies Departments for helping me become the choreographer, dancer, and thinker I am today, and of course my fellow majors, who have never stopped teaching and inspiring me. To the toothbrush owners and dinner patrons of 43A Home Avenue, thank you. Kathleen, David, and Martha Fischhoff, thank you for making all things possible. Introduction Even a cursory glance at contemporary media shows the vital place astronauts have come to occupy in the national imagination of the United States. Space Camp, located at 1 Tranquility Base in Huntsville, AL offers day and residential programs for children ages 7 to 18. The camp’s website also advertises programs designed for corporate groups, educators, and “Special Programs” for the visually impaired and hard of hearing. The space-related work of Hollywood icon Tom Hanks alone includes film (Apollo 13), a televised miniseries (From Earth to the Moon), an IMAX movie (Magnificent Desolation: Walking on the Moon 3D), and the forward to a recent popular science book (Andrew Chaikin’s A Man on the Moon). -

Copyrighted Material

JWST465-IND JWST465-Wang Printer: June 11, 2014 12:35 Trim: 244mm × 170mm Index abstract words, 327 Apel, K., 193 Batshaw, M. L., 170 academic language, 7–8, 11, apprenticeship, 200 Bauer, D. J., 45 see also academic language appropriate, 201 Bear,D.R.,204 register aptitude, 231–232 Beck, I. L., 204–207 academic language register, 201 Archibald, L. M. D., 127 Becker,J.A.,48 academic literacy, 7–8, 198–9, Ashmore, R. A., 196 behaviorist perspective/theory, 221, 303, 307, 333–4, 342, Aslin,R.N.,68 379–380 361 augmentative and alternative Benko, S. L., 312, 313, 353 accountable talk, 310 communication (AAC), Berk, L. E., 82, 293 acquisition/learning hypothesis, 169–170 Berko, J., 76 389 autism spectrum disorder (ASD), Berman,R.A.,189 Acredolo, L., 87, 139 2, 147, 152, 261 Bernardini, P., 387 Adams, M. J., 53 autobiographical memory, 265, Bertelson, P., 152, 261 adverbial conjuncts, 297–8 281 Bhatia, T. K., 115, 122, 142 adverbial disjuncts, 297 automaticity, 240 Bialystok, E., 51, 53, 54, 113, affective filter hypothesis, 390 avoidance strategy, 323 116, 126, 134, 238 affective filters, 233 Biancarosa, C., 313, 314 affricates/affricatives, 124 Baba, J., 330, 331, 353 Bickerton, D., 37, 39 African American English (AAE), babble, 70, 122 bidialect, 301–303, 316, 317 87, 199, 301 baby talk, see motherese bilingual first language acquisition agency, 383 Baker, C., 113, 120, 131, 388, (BFLA), 55, 114, 142 Aitchison, J., 75 389 Bishop, D. V. M., 29, 147, 154, Alfassi, M., 210 Baker, S. E., 55 155 Alfieri, L., 307 Ball, A. -

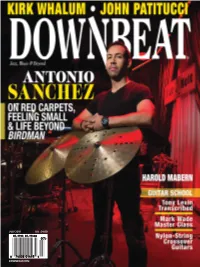

Downbeat.Com July 2015 U.K. £4.00

JULY 2015 2015 JULY U.K. £4.00 DOWNBEAT.COM DOWNBEAT ANTONIO SANCHEZ • KIRK WHALUM • JOHN PATITUCCI • HAROLD MABERN JULY 2015 JULY 2015 VOLUME 82 / NUMBER 7 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ĺDQHWDÎXQWRY£ Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Stephen Hall ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, -

Broadway Starts to Rock: Musical Theater Orchestrations and Character, 1968-1975 By

Broadway Starts to Rock: Musical Theater Orchestrations and Character, 1968-1975 By Elizabeth Sallinger M.M., Duquesne University, 2010 B.A., Pennsylvania State University, 2008 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Musicology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chair: Paul R. Laird Roberta Freund Schwartz Bryan Kip Haaheim Colin Roust Leslie Bennett Date Defended: 5 December 2016 ii The dissertation committee for Elizabeth Sallinger certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Broadway Starts to Rock: Musical Theater Orchestrations and Character, 1968-1975 Chair: Paul R. Laird Date Approved: 5 December 2016 iii Abstract In 1968, the sound of the Broadway pit was forever changed with the rock ensemble that accompanied Hair. The musical backdrop for the show was appropriate for the countercultural subject matter, taking into account the popular genres of the time that were connected with such figures, and marrying them to other musical styles to help support the individual characters. Though popular styles had long been part of Broadway scores, it took more than a decade for rock to become a major influence in the commercial theater. The associations an audience had with rock music outside of a theater affected perception of the plot and characters in new ways and allowed for shows to be marketed toward younger demographics, expanding the audience base. Other shows contemporary to Hair began to include rock music and approaches as well; composers and orchestrators incorporated instruments such as electric guitar, bass, and synthesizer, amplification in the pit, and backup singers as components of their scores.