In Search of Authenticity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monasticism” and the Vocabulary of Religious Life

What Do We Call IT? New “Monasticism” and the Vocabulary of Religious Life “The letter of the Rule was killing, and the large number of applicants and the high rate of their subsequent leaving shows the dichotomy: men were attracted by what Merton saw in monasticism and what he wrote about it, and turned away by the life as it was dictated by the abbot.” (Edward Rice, The Man in the Sycamore Tree: The good times and hard life of Thomas Merton, p. 77) “Fourth, the new monasticism will be undergirded by deep theological reflection and commitment. by saying that the new monasticism must be undergirded by theological commitment and reflection, I am not saying that right theology will of itself produce a faithful church. A faithful church is marked by the faithful carrying out of the mission given to the church by Jesus Christ, but that mission can be identified only by faithful theology. So, in the new monasticism we must strive simultaneously for a recovery of right belief and right practice.” (Jonathan R. Wilson, Living Faithfully in a Fragmented World: Lessons for the Church from MacIntyre’s After Virtue [1997], pp. 75-76 in a chapter titled “The New Monasticism”) Whether we like the term or not, it is here, probably to stay. “Monasticism.” Is that what it is, new “monasticism”? Is that what we should call it? The problem begins when you try to choose a textbook that covers the history of things. Histories of monasticism only cover the enclosed life. Celtic monasticism prior to Roman adoption is seldom covered. -

Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2009 Issue 4 CoJS Newsletter • March 2009 • Issue 4 Centre for Jaina Studies' Members _____________________________________________________________________ SOAS MEMBERS EXTERNAL MEMBERS Honorary President Paul Dundas Professor J Clifford Wright (University of Edinburgh) Vedic, Classical Sanskrit, Pali, and Prakrit Senior Lecturer in Sanskrit language and literature; comparative philology Dr William Johnson (University of Cardiff) Chair/Director of the Centre Jainism; Indian religion; Sanskrit Indian Dr Peter Flügel Epic; Classical Indian religions; Sanskrit drama. Jainism; Religion and society in South Asia; Anthropology of religion; Religion ASSOCIATE MEMBERS and law; South Asian diaspora. John Guy Professor Lawrence A. Babb (Metropolitan Mueum of Art) Dr Daud Ali (Amherst College) History of medieval South India; Chola Professor Phyllis Granoff courtly culture in early medieval India Professor Nalini Balbir (Yale University) (Sorbonne Nouvelle) Dr Crispin Branfoot Dr Julia Hegewald Hindu, Buddhist and Jain Architecture, Dr Piotr Balcerowicz (University of Manchester) Sculpture and Painting; Pilgrimage and (University of Warsaw) Sacred Geography, Archaeology and Professor Rishabh Chandra Jain Material Religion; South India Nick Barnard (Muzaffarpur University) (Victoria and Albert Museum) Professor Ian Brown Professor Padmanabh S. Jaini The modern economic and political Professor Satya Ranjan Banerjee (UC Berkeley) history of South East Asia; the economic (University of Kolkata) -

Introducing New Monasticism

AAR October 2, 2008 Christian Spirituality Group “The New Monasticism” Evan Howard, presiding Introducing New Monasticism Welcome to the Christian Spirituality Group of the American Academy of Religion. This afternoon our topic of discussion is “the new monasticism.” We have a delightful set of contributions to our discussion provided by our three presenters, Brian Campbell, Philip Harrold, and Martha McAfee. My name is Evan Howard, and I will, by way of introduction, provide an overview of new monastic phenomena. So, just what is “new monasticism”? The answer to that question depends on where you draw your circle. The fact of the matter is intentional communities and ascetical or alternative expressions are forming all the time. There is the global spread of the French-born Community of the Beatitudes. There are the groups connected with the Northumbria Community in the UK--who commit to a set of common values and practices and who maintain mutual accountability and encouragement largely through email contact. We could discuss the shifts in the character of quasi-Anarchist collectives in the West. And so on. As with the history of religious life more generally, the forms of new experiments in Christian living vary greatly. There are “new friars,” small teams of missionaries sharing Christ in deed and word among the poor of the world. There are “new siblings of the common life,” drawing from the heritage of monasticism to form communities of solidarity and influence. There are “new solitaries,” experimenting with the life and ministry of the hermit. Once again, many expressions could be explored. In light of the summary presented in your program book, I will focus my attention on those groups recently comprehended under the labels “new monasticism,” and “new friars.” The historical development of new monasticism can be divided into three seasons. -

The Beguine Option: a Persistent Past and a Promising Future of Christian Monasticism

religions Article The Beguine Option: A Persistent Past and a Promising Future of Christian Monasticism Evan B. Howard Department of Ministry, Fuller Theological Seminary 62421 Rabbit Trail, Montrose, CO 81403, USA; [email protected] Received: 1 June 2019; Accepted: 3 August 2019; Published: 21 August 2019 Abstract: Since Herbert Grundmann’s 1935 Religious Movements in the Middle Ages, interest in the Beguines has grown significantly. Yet we have struggled whether to call Beguines “religious” or not. My conviction is that the Beguines are one manifestation of an impulse found throughout Christian history to live a form of life that resembles Christian monasticism without founding institutions of religious life. It is this range of less institutional yet seriously committed forms of life that I am here calling the “Beguine Option.” In my essay, I will sketch this “Beguine Option” in its varied expressions through Christian history. Having presented something of the persistent past of the Beguine Option, I will then present an introduction to forms of life exhibited in many of the expressions of what some have called “new monasticism” today, highlighting the similarities between movements in the past and new monastic movements in the present. Finally, I will suggest that the Christian Church would do well to foster the development of such communities in the future as I believe these forms of life hold much promise for manifesting and advancing the kingdom of God in our midst in a postmodern world. Keywords: monasticism; Beguine; spiritual formation; intentional community; spirituality; religious life 1. Introduction What might the future of monasticism look like? I start with three examples: two from the present and one from the past. -

New Monasticism

A publication of the INTERCOMMUNITY PEACE & JUSTICE CENTER NO. 117 / WINTER 2018 New Monasticism The topic of this issue of A Matter of Spirit is the “New Monasticism.” What do you Living Monasticism think of when you hear the By Christine Valters Paintner journeying with others who are also strug- word “monastic?” Do you gling against busyness, debt and divisive- picture a solitary monk in a Over the last twenty years there has been ness. hermitage far from town? a great renewal of interest in the monastic The root of the word monk is monachos, Do you think of a medieval life, but this time from those who find them- which means single-hearted. To become a community reciting prayers in Latin? Or do you think of selves wanting to live outside the walls of the monk in the world means to keep one’s focus a group of millennials living cloister. It was this desire that led me fifteen on the love at the heart of everything. This is and working together today? years ago to become a Benedictine oblate. available to all of us, regardless of whether Each of these, and more, are Becoming an oblate means making a com- we live celibate and cloistered, partnered and expressions of the monastic mitment to live out the Benedictine charism raising a family or employed in business. impulse, a desire to connect in daily life, at work, in a marriage and fam- The three main sources I draw upon to deeply to a life of prayer and ily, and in all the other ways ordinary people sustain me in this path are the Rule of Bene- service in community with interact with the world on a daily basis. -

Anabaptism: the Beginning of a New Monasticism

[A paper given at “Christian Mission in the Public Square”, a conference of the Australian Association for Mission Studies (AAMS) and the Public and Contextual Theology Research Centre of Charles Sturt University, held at the Australian Centre for Christianity and Culture (ACC&C) in Canberra from 2 to 5 October 2008.] Anabaptism: The Beginning of a New Monasticism by Mark S. Hurst Introduction Wolfgang Capito, a Reformer in Strasbourg, wrote a letter to the Burgermeister and Council at Horb in May 1527 warning about the Anabaptist leader Michael Sattler. He was worried that Sattler was bringing about “the beginning of a new monasticism.” (Yoder, 87) Both Anabaptism and “new monasticism” are being explored today as relevant expressions of the Christian faith in our post-Christendom environment. The connections between these two movements will be examined in a conference sponsored by the Anabaptist Association of Australia and New Zealand in January 2009 as they were in a recent conference in Great Britain called “New Habits for a New Era? Exploring New Monasticism,” co-sponsored by the British Anabaptist Network and the Northumbria Community. (See http://www.anabaptistnetwork.com/node/19 for papers from the conference.) The British gathering raised a number of questions for these movements: “We hear many stories of ‘emerging churches’ and ‘fresh expressions of church’, but Christians in many places are also rediscovering older forms of spirituality and discipleship. Some are drawing on the monastic traditions to find resources for a post- Christendom culture. ‘New monasticism’ is the term many are using to describe these attempts to re-work old rhythms, rules of life and liturgical resources in a new era. -

Monastic Missional Pilgrim Communities in Liquid Modern Spain Garrick C

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Doctor of Ministry Theses and Dissertations 3-1-2015 Monastic Missional Pilgrim Communities in Liquid Modern Spain Garrick C. Roegner George Fox University, [email protected] This research is a product of the Doctor of Ministry (DMin) program at George Fox University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Roegner, Garrick C., "Monastic Missional Pilgrim Communities in Liquid Modern Spain" (2015). Doctor of Ministry. Paper 96. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dmin/96 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Ministry by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GEORGE FOX UNIVERSITY MONASTIC MISSIONAL PILGRIM COMMUNITIES IN LIQUID MODERN SPAIN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GEORGE FOX EVANGELICAL SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY GARRICK C. ROEGNER PORTLAND, OREGON MARCH 2015 George Fox Evangelical Seminary George Fox University Portland, Oregon CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL ________________________________ DMin Dissertation ________________________________ This is to certify that the DMin Dissertation of Garrick C. Roegner has been approved by the Dissertation Committee on March 3, 2015 for the degree of Doctor of Ministry in Leadership and Global Perspectives. Dissertation Committee: Primary Advisor: Peter Aschoff, -

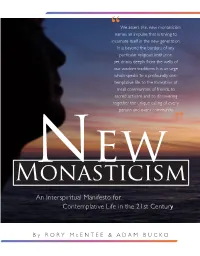

New Monasticism Names an Impulse That Is Trying to Incarnate Itself in the New Generation

“We assert that new monasticism names an impulse that is trying to incarnate itself in the new generation. It is beyond the borders of any particular religious institution, yet drinks deeply from the wells of our wisdom traditions. It is an urge which speaks to a profoundly con- templative life, to the formation of small communities of friends, to sacred activism and to discovering together the unique calling of every person and every community. ” ew MonasticismN An Interspiritual Manifesto for Contemplative Life in the 21st Century By RORY McENTEE & ADAM BUCKO In Gratefulness here have been many inspirations and guides on the road to new monasticism. TBefore we begin we must offer our deepest gratitude and thanks to all whose ideas, lives, mentorship and presence have brought us here. To name but a very few of these pioneers: Father Bede Griffiths, Ramon Panikkar, Thomas Merton, Father Thomas Keating, Brother Wayne Teasdale, Andrew Harvey, Matthew Fox, Kurt Johnson, Cecil Collins, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Dorothy Day, Pir Hazrat Inayat Khan and Pir Zia Inayat Khan, Catherine Doherty, Madeleine Delbrel, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Father Richard Rohr, Mother Teresa, the Hermits of Peace at Sky Farm Hermitage, Brother Francis Ali and Sister Michaela Terrio, and many others, with special gratitude to those Sufi and Hasidic wisdom makers for whom “the world was never taken outside of the monastery”... C Prologue “What we seek is an experience that transforms our lives and incorporates us into the destiny of the universe. We are looking -

Contemplative Mysticism: a Powerful Ecumenical Bond Copyright 2008 by David W

Contemplative Mysticism: A Powerful Ecumenical Bond Copyright 2008 by David W. Cloud Second edition November 2008 Tis edition February 11, 2016 ISBN 978-1-58318-113-3 Published by Way of Life Literature P.O. Box 610368, Port Huron, MI 48061 866-295-4143 (toll free) • [email protected] http://www.wayofife.org Canada: Bethel Baptist Church, 4212 Campbell St. N., London, Ont. N6P 1A6 519-652-2619 Printed in Canada by Bethel Baptist Print Ministry 2 Contents What is Mysticism?............................................................... 5 A Defnition of Mysticism ..................................................6 Te Taizé Approach .............................................................9 Richard Foster: Evangelicalism’s Mystical Sparkplug .......11 The Widespread Influence of Mysticism ............................40 Mysticism Is Found in All Branches of the Emerging Church ...........................................................................40 Mysticism Is Spreading Troughout Evangelicalism ....45 A Description of the Contemplative Practices ....................85 Centering Prayer ................................................................85 Visualization or Imaginative Prayer ................................91 Te Jesus Prayer .................................................................97 Te Breath Prayer ...............................................................98 Lectio Divina ......................................................................99 Te Stations of the Cross ................................................106 -

A New Zealand Contextual Church Model That Fosters Community and Discipleship

Ministry Focus Paper Approval Sheet This ministry focus paper entitled A NEW ZEALAND CONTEXTUAL CHURCH MODEL THAT FOSTERS COMMUNITY AND DISCIPLESHIP Written by DARRYL TEMPERO and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Ministry has been accepted by the Faculty of Fuller Theological Seminary upon the recommendation of the undersigned reader: _____________________________________ Kurt Fredrickson Date Received: March 20, 2017 A NEW ZEALAND CONTEXTUAL CHURCH MODEL THAT FOSTERS COMMUNITY AND DISCIPLESHIP A FINAL PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY FULLER THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY DARRYL TEMPERO FEBRUARY 2017 ABSTRACT A New Zealand Contextual Church Model that Fosters Community and Discipleship Darryl Tempero Doctor of Ministry School of Theology, Fuller Theological Seminary 2017 The goal of this project was to discover a church model that helps de-churched New Zealanders grow as followers of Jesus and in relationships with each other. The strategy followed was to include the de-churched in the identification of activities that they believed would help their formation. The context of this study was the Kiwi Church faith community, a new church congregation of the Presbyterian Church of Aotearoa, New Zealand. The study led to the definition of church for this community as “Doing life with Jesus, and each other.” Six participants were interviewed at the beginning of the project to gain an understanding of their current level of spirituality, and identify possible activities to experiment with. The activities, along with other spiritual exercises identified by the author, were experimented with over a period of eighteen months, and then the participants interviewed again. -

The 'New Monasticism' As Ancient

AAR 2008 – Christian Spirituality Group – “New Monasticism” – Philip Harrold [please do not cite without permission of the author] The ‘New Monasticism’ as Ancient-Future Belonging: Imagination and Memory in the Emerging Church by Philip Harrold Associate Professor of Church History Trinity School for Ministry Ambridge PA “More substantial than a trend but less organized than a movement.” That’s how a recent cover story in U. S. News & World Report described the “return to tradition” in contemporary North American religions.1 In Protestant Christian circles, the “new interest in old ways” has been around since Robert Webber published Evangelicals on the Canterbury Trail in 1985. His “ancient-future” project shifted from description to prescription, showing amnesia-prone evangelicals how the future led to, or at least through, the past.2 Meanwhile Colleen Carroll traced similar impulses among younger Catholics in her book The New Faithful: Why Young Adults are Embracing Christian Orthodoxy (2002). Sociologist of religion Roger Finke has observed an “innovative return to tradition,” while social psychologist Philip Wexler documents “cultural changes toward the sacred” that renew “esoteric traditions” and “mystical practice and theory.”3 In the wake of the New Age, Madonna’s dabblings in Kabala caused skeptics— from inside and outside the traditions themselves—to question the seriousness or scope of the phenomenon. Yet despite the occasional hype and celebrity, there are persistent signs of a growing historical consciousness or, better yet, -

In Search of the New Monasticism

Obsculta Volume 4 Issue 1 Article 9 5-1-2010 Something Old, Something New: In Search of the New Monasticism Julian Collette College of Saint Benedict/Saint John's University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/obsculta Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons ISSN: 2472-2596 (print) ISSN: 2472-260X (online) Recommended Citation Collette, Julian. 2011. Something Old, Something New: In Search of the New Monasticism. Obsculta 4, (1) : 22-28. https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/obsculta/vol4/iss1/9. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Obsculta by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Something Old, Something New: Julian Collette In Search of the New Monasticism Julian Collette is a student of monastic studies and pastoral ministry. He has lived in various inten- tional communities such as New Camaldoli Hermitage in Big Sur, California, and an Ecovillage and Zen Buddhist Meditation Center in Massachusetts. In June 2011, as part of his academic program at Saint John’s Theology•Seminary, Julian will embark on a 14 month bicycle tour of the United Stated, visiting various intentional communities including those identified with the New Monasticism move- ment. Along the way he will conduct interviews which will be made available in a podcast. Julian’s journey can be followed by visiting: www.emerging-communities.com.