Profiles in Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liberalism, Neutrality and the Politics of Virtue

Koray Tütüncü Liberalism, neutrality and the politics of virtue Abstract The relationship between politics and virtue has been a controversial issue. Some significant scholars make a sharp distinction between what is political and what is not, but others underline the impossibility of separating politics from virtue. This article aims to re-consider the problem of virtue in terms of liberal politics. In doing so, it distinguishes three different arguments, namely the ‘inescapability of virtue’, ‘virtue lost’ and ‘reclamation of virtue’ arguments. The first argument underlines the impossibility of separating politics from virtue; the second shows the impossibility of virtuous politics in modern liberal politics; while the third criticises liberal neu- trality and individualism which undermines virtue politics. This article offers in their place a Rawlsian solution which centralises justice as the first virtue of a well-or- dered liberal society. It argues that, without negotiating fundamental rights and equal liberties, a Rawlsian solution transcends the limitations of liberal neutrality by articulating political virtuousness into liberalism. The result is that it concludes that liberal democracies would be politically virtuous without imposing any particular virtuous life conceptions. Keywords: virtue, liberal politics, good life, procedural and substantive neutrality, inequalities, justice, rights, perfectionism, freedoms, obligations, relativism, utili- tarian, Kantian, communitarian, individualism Introduction The relationship between politics and virtue has long been a controversial issue. Some significant political scholars make a sharp distinction between what is political and what is not, and consider morality and virtues as apolitical issues,1 while others underline the impossibility of separating politics from virtues, despite a unity of polit- ical and virtuous lives having been more apparent in ancient and medieval times.2 Some argue that modernity aims to separate politics not only from the religious but also from the virtuous. -

After Virtue Chapter Guide

After Virtue After Virtue by Alasdair MacIntyre. Wikipedia has a very useful synopsis (permalink as accessed Dec 9 2008). Citations refer to the 1984 second edition, ISBN 0268006113. Chapter Summary A note and disclaimer about the chapter summary: This summary is intended only to supplement an actual reading of the text. It is not sufficient in and of itself to understand MacIntyre's theory without having read the book, and even having read it, this guide is not sufficient to understand it in its entirety. A necessary amount of detail and nuance was eliminated in order to create the guide. Its intended purpose is to aid in comprehension of this complex but profoundly significant work during and after the process of reading it. I would suggest reading the synopsis of each chapter after reading the chapter. The goal is to present the outline of MacIntyre's claims and arguments with only a minimal gloss on the justifying evidence at each point. Thus, hopefully, the guide should prove reasonably sufficient to help a reader retain the crucial parts of MacIntyre's argument, and the text can be returned to for a full justification. It is easy to get bogged down in this book, but just take your time. No portion of his argument can be fully understood without understanding the whole— nevertheless, certain chapters deserve particular attention: Chapters 1-5, 9, 14, and 15. Enjoy. —Ari Schulman ([email protected]), Dec 9 2008 Chapter 1. A Disquieting Suggestion MacIntyre imagines a world in which the natural sciences "suffer the effects of a catastrophe": the public turns against science and destroys scientific knowledge, but later recants and revives science (1). -

Mission History and Partners Recommended Reading

Global Ministries—UCC & Disciples Middle East and Europe Mission History and Partners Recommended Reading Christianity: A History in the Middle East, edited by Rev. Habib Badr—This large tome is a collection of articles about the history of Christianity and churches of the countries of the Middle East. Comprehensive and thorough, this book was undertaken by the Middle East Council of Churches and was first available in Arabic. This translation will be of interest to any student of Middle Eastern Christianity. The Arab Christian: A History in the Middle East , by Kenneth Cragg—This book was published in the 1990’s but is indispensible in gaining an historical and contemporary perspective on Arab Christianity. It is a thoroughly researched book, and is not light reading! Cragg lived and served in the Middle East; he is and Anglican bishop. He has studies and written about Christian- Muslim relations extensively, and knows the Christian community well. He discusses history, sociology, the arts, and Christian- Muslim relations in this book. In some places, he over-simplifies my referring to an “Arab mind” or a “Muslim mind,” an approach which is rebuked by Edward Said in Orientalism , but Cragg’s study is quite valuable nonetheless. Jesus Wars , by Philip Jenkins—This book will offer much insight into the Orthodox traditions as it explores theological and Christological debates of the early church. Focusing on the ecumenical councils of the fourth century, the reader will have a better understanding of the movements within, and resultant splits of, the church. Not limited to theological debate, these divisions had to do with political and personal power as well. -

Educating for Peace and Justice: Religious Dimensions, Grades 7-12

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 392 723 SO 026 048 AUTHOR McGinnis, James TITLE Educating for Peace and Justice: Religious Dimensions, Grades 7-12. 8th Edition. INSTITUTION Institute for Peace and Justice, St. Louis, MO. PUB DATE 93 NOTE 198p. AVAILABLE FROM Institute for Peace and Justice, 4144 Lindell Boulevard, Suite 124, St. Louis, MO 63108. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Conflict Resolution; Critical Thinking; Cross Cultural Studies; *Global Education; International Cooperation; *Justice; *Multicultural Education; *Peace; *Religion; Religion Studies; Religious Education; Secondary Education; Social Discrimination; Social Problems; Social Studies; World Problems ABSTRACT This manual examines peace and justice themes with an interfaith focus. Each unit begins with an overview of the unit, the teaching procedure suggested for the unit and helpful resources noted. The volume contains the following units:(1) "Of Dreams and Vision";(2) "The Prophets: Bearers of the Vision";(3) "Faith and Culture Contrasts";(4) "Making the Connections: Social Analysis, Social Sin, and Social Change";(5) "Reconciliation: Turning Enemies and Strangers into Friends";(6) "Interracial Reconciliation"; (7) "Interreligious Reconciliation";(8) "International Reconciliation"; (9) "Conscientious Decision-Making about War and Peace Issues"; (10) "Solidarity with the Poor"; and (11) "Reconciliation with the Earth." Seven appendices conclude the document. (EH) * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are -

The Schematic of God

The Schematic of God For The First Time An Extraordinary Journey Into Humanity’s Nonphysical Roots Warning! Reading this material may change your reality. William Dayholos January/2007 © E –mail address: [email protected] ISBN: 978-1-4251-2303-1 Paperback copy can be ordered from Trafford Publishing – www.trafford.com Illustrations by Wm. Dayholos ©Copyright 2007 William Dayholos II Acknowledgments The value of ones existences can always be measured by the support they receive from others. Be it family or not it is still unselfish support for another human being who is asking for help. Thank you Rose Dayholos, Marjory Marciski, Irene Sulik, Grace Single, Janice Abstreiter, and Robert Regnier for your editing help. This book is dedicated to my partner in life. To me a partner is one whom you can share your ideas with, one who can be trusted not to patronize these ideas, one who can differentiate their own truth from yours. A person who has an equal spiritual level and understanding, and encourages only through support of your ideas and not to through expectation. A true partner is one who balances out any weaknesses you have in the same fashion as you do for them. One’s weakness is the other’s strength, together you create a whole, a relationship that is stronger than the individuals themselves. In true fashion my partner has both helped and supported this book’s creation. Without this partner’s help it might have run the risk of being too much “me”! This was never the reason for the book. -

The Idea of a Communitarian Morality

The Idea of a Communitarian Morality Philip Selznickt During the past few years, and especially since the publication of Alasdair MacIntyre's After Virtue in 1981, we have seen a renewed attack on the premises of liberalism.' There is nothing new about such criticism. A long list of writers-Hegel, Marx, Dewey, and many others, including several Popes-have recoiled in various ways from what seemed to be an impoverished morality and an inadequate understanding of human society. The contemporary criticism has raised some new issues and has been sparked, in no small degree, by a spate of impressive writing in legal, moral, and social philosophy-writing that has reaf- firmed the liberal faith in moral autonomy and in the imperatives of rationality. I refer, of course, to the work of John Rawls, Robert Nozick, and Ronald Dworkin. The new critics are called communitarian, an echo of similar views expressed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries by English liberals like John A. Hobson and L.T. Hobhouse, and American pragmatists, especially John Dewey. Yet the communitarian idea is vague; in contemporary writing it is more often alluded to and hinted at than explicated. Furthermore, there are communitarians on both left and right. The quest for a communitarian morality is a meeting ground for conservatives, socialists, anarchists, and more ambiguously, welfare liber- als. Serious issues of social policy are at stake. It seems important, there- fore, to explore what a communitarian morality may entail. For if we shoot these arrows of the spirit we should know, as best we can, where they will light. -

Read Book Blood Brothers the Dramatic Story of a Palestinian

BLOOD BROTHERS THE DRAMATIC STORY OF A PALESTINIAN CHRISTIAN WORKING FOR PEACE IN ISRAEL 2ND EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Elias Chacour | 9780800793210 | | | | | Blood Brothers The Dramatic Story of a Palestinian Christian Working for Peace in Israel 2nd edition PDF Book Being that we are an Orthodox Christian family, I also had some concerns about how the overall Christian connection would be framed. I learned so much from this book. Fantasy written in page-turner thriller style. Baker's own efforts toward Holy Land peace makes his foreword all the more influential as well as informative for the reader. Who is the fighter for liberty? Thanks for emphasising the importance of a balanced stand against violence from all sides and thanks for reigniting a tiny glimmer of hope for peace when people who follow Jesus aim to be spokespeople for reconciliation. Christians have lived in Palestine since the earliest days of the Jesus movement. But early in , their idyllic lifestyle was swept away as tens of thousands of Palestinians were killed and nearly one million forced into refugee camps. Showing About Elias Chacour. Anonymous User It means we conquer by stooping, by serving with love and kindness, even if it means personal danger or financial hardship. I know you know. We have reduced the kingdom of God to private piety; the victory of the cross to comfort for the conscience; Easter itself to a happy, escapist ending after a sad, dark tale. I learned a lot about the Palestinian experience post-WWII, beginning with the arrival of the Zionists and the takeover of land and village. -

Monasticism” and the Vocabulary of Religious Life

What Do We Call IT? New “Monasticism” and the Vocabulary of Religious Life “The letter of the Rule was killing, and the large number of applicants and the high rate of their subsequent leaving shows the dichotomy: men were attracted by what Merton saw in monasticism and what he wrote about it, and turned away by the life as it was dictated by the abbot.” (Edward Rice, The Man in the Sycamore Tree: The good times and hard life of Thomas Merton, p. 77) “Fourth, the new monasticism will be undergirded by deep theological reflection and commitment. by saying that the new monasticism must be undergirded by theological commitment and reflection, I am not saying that right theology will of itself produce a faithful church. A faithful church is marked by the faithful carrying out of the mission given to the church by Jesus Christ, but that mission can be identified only by faithful theology. So, in the new monasticism we must strive simultaneously for a recovery of right belief and right practice.” (Jonathan R. Wilson, Living Faithfully in a Fragmented World: Lessons for the Church from MacIntyre’s After Virtue [1997], pp. 75-76 in a chapter titled “The New Monasticism”) Whether we like the term or not, it is here, probably to stay. “Monasticism.” Is that what it is, new “monasticism”? Is that what we should call it? The problem begins when you try to choose a textbook that covers the history of things. Histories of monasticism only cover the enclosed life. Celtic monasticism prior to Roman adoption is seldom covered. -

Integrating Differentiated Instruction & Understanding by Design

Integrating Differentiated Instruction & Understanding by Design: Connecting Content and Kids by Carol Ann Tomlinson and Jay McTighe Chapter 1. UbD and DI: An Essential Partnership What is the logic for joining the two models? What are the big ideas of the models, and how do they look in action? Understanding by Design and Differentiated Instruction are currently the subject of many educational conversations, both in the United States and abroad. Certainly part of the reason for the high level of interest in the two approaches to curriculum and teaching is their logical and practical appeal. Beset by lists of content standards and accompanying “high-stakes” accountability tests, many educators sense that both teaching and learning have been redirected in ways that are potentially impoverishing for those who teach and those who learn. Educators need a model that acknowledges the centrality of standards but that also demonstrates how meaning and understanding can both emanate from and frame content standards so that young people develop powers of mind as well as accumulate an information base. For many educators, Understanding by Design addresses that need. Simultaneously, teachers find it increasingly difficult to ignore the diversity of learners who populate their classrooms. Culture, race, language, economics, gender, experience, motivation to achieve, disability, advanced ability, personal interests, learning preferences, and presence or absence of an adult support system are just some of the factors that students bring to school with them in almost stunning variety. Few teachers find their work effective or satisfying when they simply “serve up” a curriculum—even an elegant one—to their students with no regard for their varied learning needs. -

New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry

New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry by Evan Landon Wendel B.S. Physics Hobart and William Smith Colleges, 2004 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2008 © 2008 Evan Landon Wendel. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: _______________________________________________________ Program in Comparative Media Studies May 9, 2008 Certified By: _____________________________________________________________ William Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies Thesis Supervisor Accepted By: _____________________________________________________________ Henry Jenkins Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities Professor of Comparative Media Studies and Literature Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies 2 3 New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry by Evan Landon Wendel Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies on May 9, 2008 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies Abstract This thesis explores the evolving nature of independent music practices in the context of offline and online social networks. The pivotal role of social networks in the cultural production of music is first examined by treating an independent record label of the post- punk era as an offline social network. -

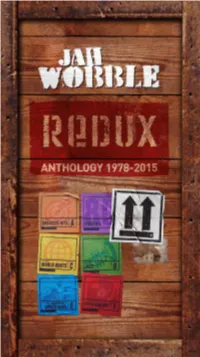

View the Redux Book Here

1 Photo: Alex Hurst REDUX This Redux box set is on the 30 Hertz Records label, which I started in 1997. Many of the tracks on this box set originated on 30 Hertz. I did have a label in the early eighties called Lago, on which I released some of my first solo records. These were re-released on 30 Hertz Records in the early noughties. 30 Hertz Records was formed in order to give me a refuge away from the vagaries of corporate record companies. It was one of the wisest things I have ever done. It meant that, within reason, I could commission myself to make whatever sort of record took my fancy. For a prolific artist such as myself, it was a perfect situation. No major record company would have allowed me to have released as many albums as I have. At the time I formed the label, it was still a very rigid business; you released one album every few years and ‘toured it’ in the hope that it became a blockbuster. On the other hand, my attitude was more similar to most painters or other visual artists. I always have one or two records on the go in the same way they always have one or two paintings in progress. My feeling has always been to let the music come, document it by releasing it then let the world catch up in its own time. Hopefully, my new partnership with Cherry Red means that Redux signifies a new beginning as well as documenting the past. -

Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2009 Issue 4 CoJS Newsletter • March 2009 • Issue 4 Centre for Jaina Studies' Members _____________________________________________________________________ SOAS MEMBERS EXTERNAL MEMBERS Honorary President Paul Dundas Professor J Clifford Wright (University of Edinburgh) Vedic, Classical Sanskrit, Pali, and Prakrit Senior Lecturer in Sanskrit language and literature; comparative philology Dr William Johnson (University of Cardiff) Chair/Director of the Centre Jainism; Indian religion; Sanskrit Indian Dr Peter Flügel Epic; Classical Indian religions; Sanskrit drama. Jainism; Religion and society in South Asia; Anthropology of religion; Religion ASSOCIATE MEMBERS and law; South Asian diaspora. John Guy Professor Lawrence A. Babb (Metropolitan Mueum of Art) Dr Daud Ali (Amherst College) History of medieval South India; Chola Professor Phyllis Granoff courtly culture in early medieval India Professor Nalini Balbir (Yale University) (Sorbonne Nouvelle) Dr Crispin Branfoot Dr Julia Hegewald Hindu, Buddhist and Jain Architecture, Dr Piotr Balcerowicz (University of Manchester) Sculpture and Painting; Pilgrimage and (University of Warsaw) Sacred Geography, Archaeology and Professor Rishabh Chandra Jain Material Religion; South India Nick Barnard (Muzaffarpur University) (Victoria and Albert Museum) Professor Ian Brown Professor Padmanabh S. Jaini The modern economic and political Professor Satya Ranjan Banerjee (UC Berkeley) history of South East Asia; the economic (University of Kolkata)