Magnetite and Hematite Intheiron Ores of the Kiruna Type and Some Other Iron Ore Types

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Recommended publications

-

Tourmaline Announces Formation of Topaz Energy, Unlocking Value in Tourmaline's Significant Asset Base

NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION IN THE UNITED STATES OR DISSEMINATION OVER UNITED STATES NEWSWIRE SERVICES. NEWS RELEASE OCTOBER 10, 2019 TOURMALINE ANNOUNCES FORMATION OF TOPAZ ENERGY, UNLOCKING VALUE IN TOURMALINE'S SIGNIFICANT ASSET BASE Calgary, Alberta - Tourmaline Oil Corp. (TSX:TOU) ("Tourmaline") is pleased to announce the formation of Topaz Energy Corp. (“Topaz”), a new private royalty and infrastructure energy company. Tourmaline will sell to Topaz: a royalty interest on Tourmaline lands, a non-operated interest in two of Tourmaline‘s existing 19 natural gas processing plants, and a contracted interest in a portion of Tourmaline‘s current third-party revenue for total cash and share consideration of $775 million. Topaz will be a low-risk, high-distribution, hybrid royalty and infrastructure energy company with long-term growth plans. Topaz will be capitalized initially with a $150 to $200 million third-party equity private placement, with Tourmaline retaining a 75% to 81% equity ownership interest. Tourmaline intends to reduce a portion of its ownership as Topaz participates in future acquisition activities and an anticipated Topaz public liquidity event in 2020. The initial acquisition from Tourmaline is expected to generate approximately $90 million in revenue(1) in 2020, of which it is anticipated approximately 75% will be paid out in quarterly dividends ($0.80 per share annually, 8% yield). The assets to be acquired from Tourmaline will consist of three components: 1. A gross overriding royalty (“GORR”) on natural gas, oil, and condensate production on 100% of Tourmaline’s existing lands (approximately 2.2 million net acres). 2. A non-operated 45% working interest in two natural gas processing plants underpinned by long-term take- or-pay commitments from Tourmaline. -

Lapidary Journal Jewelry Artist March 2012

INDEX TO VOLUME 65 Lapidary Journal Jewelry Artist April 2011-March 2012 INDEX BY FEATURE/ Signature Techniques Part 1 Resin Earrings and Pendant, PROJECT/DEPARTMENT of 2, 20, 09/10-11 30, 08-11 Signature Techniques Part 2 Sagenite Intarsia Pendant, 50, With title, page number, of 2, 18, 11-11 04-11 month, and year published Special Event Sales, 22, 08-11 Silver Clay and Wire Ring, 58, When to Saw Your Rough, 74, 03-12 FEATURE ARTICLES Smokin’*, 43, 09/10-11 01/02-12 Argentium® Tips, 50, 03-12 Spinwheel, 20, 08-11 Arizona Opal, 22, 01/02-12 PROJECTS/DEMOS/FACET Stacking Ring Trio, 74, Basic Files, 36, 11-11 05/06-11 DESIGNS Brachiopod Agate, 26, 04-11 Sterling Safety Pin, 22, 12-11 Alabaster Bowls, 54, 07-11 Create Your Best Workspace, Swirl Step Cut Revisited, 72, Amethyst Crystal Cross, 34, 28, 11-11 01/02-12 Cut Together, 66, 01/02-12 12-11 Tabbed Fossil Coral Pendant, Deciphering Chinese Writing Copper and Silver Clay 50, 01/02-12 Linked Bracelet, 48, 07-11 12, 07-11 Stone, 78, 01/02-12 Torch Fired Enamel Medallion Site of Your Own, A, 12, 03-12 Easier Torchwork, 43, 11-11 Copper Wire Cuff with Silver Necklace, 33, 09/10-11 Elizabeth Taylor’s Legendary Wire “Inlay,” 28, 07-11 Trillion Diamonds Barion, 44, SMOKIN’ STONES Jewels, 58, 12-11 Coquina Pendant, 44, 05/06-11 Alabaster, 52, 07-11 Ethiopian Opal, 28, 01/02-12 01/02-12 Turquoise and Pierced Silver Ametrine, 44, 09/10-11 Find the Right Findings, 46, Corrugated Copper Pendant, Bead Bracelet – Plus!, 44, Coquina, 42, 01/02-12 09/10-11 24, 05/06-11 04-11 Fossilized Ivory, 24, 04-11 -

Gem Wealth of Tanzania GEMS & GEMOLOGY Summer 1992 Fipe 1

By Dona M.Dirlarn, Elise B. Misiorowski, Rosemaiy Tozer, Karen B. Stark, and Allen M.Bassett The East African nation of Tanzania has he United Republic of Tanzania, the largest of the East great gem wealth. First known by Western- 1African countries, is composed of mainland Tanzania and ers for its diamonds, Tanzania emerged in the island of Zanzibar. 1t is regarded by many as the birthplace the 1960s as a producer of a great variety of of the earliest ancestors of Homo sapiens. To the gem indus- other gems such as tanzanite, ruby, fancy- try, however, Tanzania is one of the most promising fron- colored sapphire, garnet, and tourmaline; to date, more than 50 gem species and vari- tiers, with 50 gem species and varieties identified, to date, eties have been produced. As the 1990s from more than 200 occurrences. begin, De Beers has reinstated diamond "Modem" mining started in the gold fields of Tanzania in exploration in Tanzania, new gem materials the late 1890s (Ngunangwa, 19821, but modem diamond min- such as transparent green zoisite have ing did not start until 1925, and nearly all mining of colored appeared on the market, and there is stones has taken place since 1950. Even so, only a few of the increasing interest in Tanzania's lesser- gem materials identified have been exploited to any significant known gems such as scapolite, spinel, and extent: diamond, ruby, sapphire, purplish blue zoisite (tan- zircon. This overview describes the main zanite; figure l),and green grossular [tsavorite)and other gar- gems and gem resources of Tanzania, and nets. -

Geology and Beryl Deposits of the Peerless Pegmatite Pennington County South Dakota

Geology and Beryl Deposits of the Peerless Pegmatite Pennington County South Dakota GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 297-A This report concerns work done partly on behalj of the U. S. Atomic Energy Commission and is published with the permission of the , » Commission Geology and Beryl Deposits of the Peerless Pegmatite Pennington County South Dakota By DOUGLAS M. SHERllDAN, HAL G. STEPHENS, MORTIMER H. STAATZ and JAMES J. NORTON PEGMATITES AND OTHER PRECAMBRIAN ROCKS IN THE SOUTHERN BLACK HILLS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 297-A This report concerns work done partly on behalf of the U. S. Atomic Energy Commission and is published with the permission of the Commission UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1957 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRED A. SEATON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price $1.50 (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Page Abstract.__________________________________________ 1 Geology Continued Introduction _______________________________________ 1 Peerless pegmatite Continued Location_____________________________________ 1 Chemical composition......____________ 17 History and production________________________ 2 Origin________ ____________________ _. 18 Past and present investigations.__________________ 3 Mineral deposits_____________________________ 21 Acknowledgments__________________________ 4 Mica__ _________ _________________________ 21 Mine workings _____________________________________ -

Gemstones by Donald W

GEMSTONES By Donald W. olson Domestic survey data and tables were prepared by Nicholas A. Muniz, statistical assistant, and the world production table was prepared by Glenn J. Wallace, international data coordinator. In this report, the terms “gem” and “gemstone” mean any gemstones and on the cutting and polishing of large diamond mineral or organic material (such as amber, pearl, petrified wood, stones. Industry employment is estimated to range from 1,000 to and shell) used for personal adornment, display, or object of art ,500 workers (U.S. International Trade Commission, 1997, p. 1). because it possesses beauty, durability, and rarity. Of more than Most natural gemstone producers in the United states 4,000 mineral species, only about 100 possess all these attributes and are small businesses that are widely dispersed and operate are considered to be gemstones. Silicates other than quartz are the independently. the small producers probably have an average largest group of gemstones; oxides and quartz are the second largest of less than three employees, including those who only work (table 1). Gemstones are subdivided into diamond and colored part time. the number of gemstone mines operating from gemstones, which in this report designates all natural nondiamond year to year fluctuates because the uncertainty associated with gems. In addition, laboratory-created gemstones, cultured pearls, the discovery and marketing of gem-quality minerals makes and gemstone simulants are discussed but are treated separately it difficult to obtain financing for developing and sustaining from natural gemstones (table 2). Trade data in this report are economically viable deposits (U.S. -

"Paraíba" Tourmaline from Brazil

AN UPDATE ON “PARAÍBA” TOURMALINE FROM BRAZIL By James E. Shigley, Brian C. Cook, Brendan M. Laurs, and Marcelo de Oliveira Bernardes Vivid blue, green, and purple-to-violet cuprian elbaites, renowned in the gem trade as “Paraíba” tourma- lines, continue to be recovered in small amounts from northeastern Brazil. Since the initial discovery of this copper-bearing tourmaline in 1982, production has been sporadic and has not kept up with the strong market demand. Mining currently takes place at the original discovery—the Mina da Batalha—and at adjacent workings near São José da Batalha in Paraíba State. At least two pegmatite localities (the Mulungu and Alto dos Quintos mines) in neighboring Rio Grande do Norte State have produced limited quantities of cuprian elbaites. All of these pegmatites occur within Late Proterozoic metamorphic rocks of the Equador Formation; the source of the copper is unknown. Six blue to blue-green elbaites from Mulungu had lower copper contents (up to 0.69 wt.% CuO) than the brightly colored Mina da Batalha material reported in the literature. nusually vivid “neon” blue, green-blue, Milisenda 2001; Smith et al., 2001; Zang et al., green, and violet elbaite tourmalines first 2001). The colors of some cuprian elbaites can be Uappeared in the jewelry trade in 1989 changed by heat treatment, and some are fracture- (Koivula and Kammerling, 1989a). Some of these filled to improve their apparent clarity. colors were so striking (figure 1) that initially there During the 1990 Tucson gem show, prices for was uncertainty over the identity of the material. this material skyrocketed from a few hundred dol- Eventually it was learned that they were recovered lars to over $2,000 per carat in just four days from several small granitic pegmatite dikes at a sin- (Federman, 1990; Reilly, 1990). -

R2362-RC1885-PTOV Paraíba Tourmaline & Diamond Ring

R2362-RC1885-PTOV Paraíba Tourmaline & Diamond Ring Platinum ring featuring a 1.84 carat oval Paraíba-type tourmaline accented by 3.44 carat total weight of oval Paraíba-type tourmalines 0.24 carat total weight of round Paraíba tourmalines and 1.07 carat total weight of round diamonds. R2362-RC1885-PTOV Supporting Information and Materials Design Details Paraíba-Type Tourmaline, Paraíba Tourmaline & Diamond 3-Stone Ring Platinum, Size 6.5 1 Paraíba-type Tourmaline Oval 1.84ct. (8.67x6.92x4.80mm) - Heated 2 Paraíba-Type Tourmaline Oval 3.44ctw. (8.03x6.82x5.08mm & 8.08x7.07x4.65mm) - Heated 34 Paraíba Tourmaline Rd 0.24ctw. - Heated 66 Diamond Rd 1.07 ctw. (F+/VS+) Unique Design Traits A classic 3-stone ring is given a burst of color with three carefully matched Paraíba- type tourmalines with their vivid blue-green color; creates a statement making sized look. Tourmalines, particularly Paraíba-type, can be more fragile than other gemstones in jewelry, to protect each of the stones, they are set in a shared halo setting which is precision set with hand-drilled diamond pave. R2362-RC1885-PTOV Supporting Information and Materials Gemstone Details Paraíba-Type/Cuprian Elbaite Tourmaline & Paraíba Tourmaline Copper bearing tourmaline, more often recognized by the name Paraíba, is technically named cuprian elbaite tourmaline. As a trace element, copper is responsible for the intense neon blue hues that make Paraíba and Paraíba-type tourmalines so desirable. A stone is considered a Paraíba tourmaline if mined in the specific region in Paraíba, Brazil where the stone was first discovered in the 1980’s. -

The Occurrence of Zeunerite at Brooks Mountain Seward Peninsula Alaska

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 214 THE OCCURRENCE OF ZEUNERITE AT BROOKS MOUNTAIN SEWARD PENINSULA ALASKA By WalterS. West and Max G. White UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OFT Oscar L. Chapman, Secret GEOLOGICAL SURV W. E. Wrathe;r, Direct r THE OCCURRENCE OF ZEUNERITE ~ BROOKS MOUNTAIN SEWARD PENINSULA, SKA By Walter S. West and Max G. This report concerns work done o behalf of the U. S. Atomic Ener CoDllllis$ion and is .published with the permission of the Commission. Washington, D. C.,l952 Free on application to the Geological Survey, Washington 25, D. C. THE OCCURRENCE OF ZEUNERITE AT BROOKS MOUNTAIN SEWARD PENINSULA, ALASKA CONTENTS Page Page Abstract.................................... 1 Mineral Deposits and Introduction .. ; . 1 radioactivity studies.. 3 Geology . 2 E'oggy Day prospect. 3 Description of rock types . 2 Tourmaline No. 2 claim. 6 Slate . 2 Minor occurrences Limestone . 2 of zeunerite. 6 Granite . 2 Radioactivity of the granite. 7 Dikes............................. 3 Conclusions. 7 Structure . .. 3 Recommendation for Hydrothermal alteration of sedimen- prospecting. 7 tary rocks and granite ............ , . 3 R.eferences cited . • . 7 ILLUSTRATIONS Page Plate 1. Geologic map of the Brooks Mountain area, Teller quadrangle, Seward Peninsula, Alaska .. .. .. • . • . • Inside back cover Figure 1. Index map of the Seward Peninsula, Alaska, showing the location of the Brooks Mountain area . • . • . 2 TABLE Pa"ge Table 1. Analyses of selected samples from the Brooks Mountain area, Seward Peninsula. • . 4 ABSTRACT mineral zone may occur below the zone of oxidation at the Foggy Day prospect. Zeunerite occurs near the surface of a granite stock on the southwest flank of Brooks Mountain, INTRODUCTION Alaska. The largest deposit is at the Foggy Day prospect. -

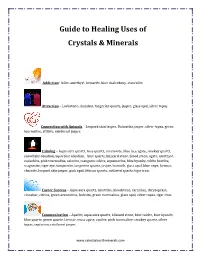

Guide to Healing Uses of Crystals & Minerals

Guide to Healing Uses of Crystals & Minerals Addiction- Iolite, amethyst, hematite, blue chalcedony, staurolite. Attraction – Lodestone, cinnabar, tangerine quartz, jasper, glass opal, silver topaz. Connection with Animals – Leopard skin Jasper, Dalmatian jasper, silver topaz, green tourmaline, stilbite, rainforest jasper. Calming – Aqua aura quartz, rose quartz, amazonite, blue lace agate, smokey quartz, snowflake obsidian, aqua blue obsidian, blue quartz, blizzard stone, blood stone, agate, amethyst, malachite, pink tourmaline, selenite, mangano calcite, aquamarine, blue kyanite, white howlite, magnesite, tiger eye, turquonite, tangerine quartz, jasper, bismuth, glass opal, blue onyx, larimar, charoite, leopard skin jasper, pink opal, lithium quartz, rutilated quartz, tiger iron. Career Success – Aqua aura quartz, ametrine, bloodstone, carnelian, chrysoprase, cinnabar, citrine, green aventurine, fuchsite, green tourmaline, glass opal, silver topaz, tiger iron. Communication – Apatite, aqua aura quartz, blizzard stone, blue calcite, blue kyanite, blue quartz, green quartz, larimar, moss agate, opalite, pink tourmaline, smokey quartz, silver topaz, septarian, rainforest jasper. www.celestialearthminerals.com Creativity – Ametrine, azurite, agatized coral, chiastolite, chrysocolla, black amethyst, carnelian, fluorite, green aventurine, fire agate, moonstone, celestite, black obsidian, sodalite, cat’s eye, larimar, rhodochrosite, magnesite, orange calcite, ruby, pink opal, blue chalcedony, abalone shell, silver topaz, green tourmaline, -

Geochemistry and Genesis of Beryl Crystals in the LCT Pegmatite Type, Ebrahim-Attar Mountain, Western Iran

minerals Article Geochemistry and Genesis of Beryl Crystals in the LCT Pegmatite Type, Ebrahim-Attar Mountain, Western Iran Narges Daneshvar 1 , Hossein Azizi 1,* , Yoshihiro Asahara 2 , Motohiro Tsuboi 3 , Masayo Minami 4 and Yousif O. Mohammad 5 1 Department of Mining Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, University of Kurdistan, Sanandaj 66177-15175, Iran; [email protected] 2 Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Graduate School of Environmental Studies, Nagoya University, Nagoya 464-8601, Japan; [email protected] 3 Department of Applied Chemistry for Environment, School of Biological and Environmental Sciences, Kwansei Gakuin University, Sanda 669-1337, Japan; [email protected] 4 Division for Chronological Research, Institute for Space-Earth Environmental Research, Nagoya University, Nagoya 464-8601, Japan; [email protected] 5 Department of Geology, College of Science, Sulaimani University, Sulaimani 46001, Iraq; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +98-918-872-3794 Abstract: Ebrahim-Attar granitic pegmatite, which is distributed in southwest Ghorveh, western Iran, is strongly peraluminous and contains minor beryl crystals. Pale-green to white beryl grains are crystallized in the rim and central parts of the granite body. The beryl grains are characterized by low contents of alkali oxides (Na2O = 0.24–0.41 wt.%, K2O = 0.05–0.17 wt.%, Li2O = 0.03–0.04 wt.%, Citation: Daneshvar, N.; Azizi, H.; and Cs2O = 0.01–0.03 wt.%) and high contents of Be2O oxide (10.0 to 11.9 wt.%). The low contents Asahara, Y.; Tsuboi, M.; Minami, M.; of alkali elements (oxides), low Na/Li (apfu) ratios (2.94 to 5.75), and variations in iron oxide Mohammad, Y.O. -

Assessment of Tourmaline As an Indicator Mineral Is Independent of the Method Chosen to Calculate Structural Formulae

Originally published as: Galbraith, C. G., Clarke, D. B., Trumbull, R. B., Wiedenbeck, M. (2009): Assessment of Tourmaline Compositions as an Indicator of Emerald Mineralization at the Tsa da Glisza Prospect, Yukon Territory, Cananda. - Economic Geology, 104, 5, 713-731 DOI: 10.2113/gsecongeo.104.5.713 Assessment of Tourmaline Compositions as an Indicator of Emerald Mineralization at the Tsa da Glisza Prospect, Yukon Territory, Canada Christopher G. Galbraith* Department of Earth Sciences, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada B3H 3J5 D. Barrie Clarke Department of Earth Sciences, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada B3H 3J5 Robert B. Trumbull GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences, Telegrafenberg, 14473 Potsdam, Germany and Michael Wiedenbeck GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences, Telegrafenberg, 14473 Potsdam, Germany Abstract Tourmaline is ubiquitous at the Tsa da Glisza emerald prospect, Yukon Territory, occurring as porphyroblasts in greenschist-facies meta-volcanic and ultramafic rocks, and as crystals in granites, aplites, and quartz-tourmaline veins. The principal occurrence of emerald is along contacts between the quartz-tourmaline veins and mafic country rocks, but it also occurs in the aplites. We assess the potential of using tourmaline compositions as a guide to emerald mineralization at Tsa da Glisza based on major-element, trace-element (Li, Be, Sc, Cr, V, Mn, Ni, Co, Cu, Zn, As, Rb, Sr, Y, Zr, Nb, Cd, Mo, Sn, Sb, Cs, Ba, Ta, W, Bi, Pb, Th, and U), REE (La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm, Eu, Yb, Lu), and boron isotopic data. The tourmaline compositions encompass Na-Fe schorl, Na-Mg dravite, and Ca-Mg uvite and show a strong dependence on host-rock chemistry. -

Hong Kong Tatler May 2016

STYLE | JEWELLERY Diamond secret watch with 33.37-carat carved tourmaline by Graff hen the surrealist its soft, muted tones, the larger pieces are designer Elsa extremely eye-catching. Schiaparelli saw the Another lovely gemstone is the peachy 17-carat vivid pink pink morganite, discovered in 1911 and diamond her glamorous named by Tiffany & Co gemmologist George client Daisy Fellowes was Kunz after the banker JP Morgan, who was wearing, she described its also a gem collector. It’s the pink translucent colour and size as “shocking.” And in 1937, variety of beryl, which includes aquamarine, when Schiaparelli created the Shoe Hat green beryl and emerald. Colour and clarity for Fellowes, the magenta of its heel was are the most important considerations, and described as “hot” for all the attention it expect to pay prices similar to those for attracted. Thanks to these two women, we quality aquamarine. Extremely feminine and have two fabulous descriptions for a flirty, pretty, morganite looks gorgeous set in rose sexy, racy pink—and what gorgeous gems gold and is perfect for brides. Add some pink there are to be deserving of such adjectives. pearls in an individual design and you have Hot-pink rubellite tourmaline is the perfect jewellery you’ll enjoy wearing long after the gemstone for women who like to stand out wedding day. in a crowd. Large, good-quality rubellites Vivid pink diamonds may be setting with no visible natural impurities (what the auction records, but exceptional stones industry calls inclusions) have a high value weighing more than three carats are very and are becoming rarer on the market, so hard to find.