Preaching Apocalyptic Texts PHILIP A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reading the Book of Revelation Politically

start page: 339 Stellenbosch eological Journal 2017, Vol 3, No 2, 339–360 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2017.v3n2.a15 Online ISSN 2413-9467 | Print ISSN 2413-9459 2017 © Pieter de Waal Neethling Trust Reading the Book of Revelation politically De Villiers, Pieter GR University of the Free State [email protected] Abstract In this essay the political use of Revelation in the first five centuries will be analysed in greatest detail, with some references to other examples. Focus will be on two trajectories of interpretation: literalist, eschatological readings and symbolic, spiritualizing interpretations of the text. Whilst the first approach reads the book as predictions of future events, the second approach links the text with spiritual themes and contents that do not refer to outstanding events in time and history. The essay will argue that both of these trajectories are ultimately determined by political considerations. In a final section, a contemporary reading of Revelation will be analysed in order to illustrate the continuing and important presence of political readings in the reception history of Revelation, albeit in new, unique forms. Key words Book of Revelation; eschatological; symbolic; spiritualizing; political considerations 1. Introduction Revelation is often associated with movements on the fringes of societies that are preoccupied with visions and calculations about the end time.1 The book has also been used throughout the centuries to reflect on and challenge political structures and 1 Cf. Barbara R. Rossing, The Rapture Exposed: the Message of Hope in the Book of Revelation (Westview Press, Boulder, CO., 2004). Robert Jewett, Jesus against the Rapture. -

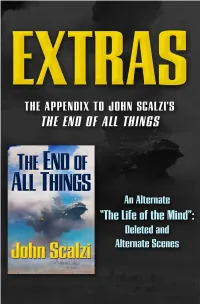

The End of All Things Took Me Longer to Write Than Most of My Books Do, in Part Because I Had a Number of False Starts

AN ALTERNATE “THE LIFE OF THE MIND” Deleted and Alternate Scenes ■■ ■■ 039-61734_ch01_4P.indd 351 06/09/15 6:17 am Introduction The End of All Things took me longer to write than most of my books do, in part because I had a number of false starts. These false starts weren’t bad—in my opinion— and they were use- ful in helping me fi gure out what was best for the book; for ex- ample, determining which point- of- view characters I wanted to have, whether the story should be in fi rst or third person, and so on. But at the same time it’s annoying to write a bunch of stuff and then go Yeaaaaah, that’s not it. So it goes. Through vari ous false starts and diversions, I ended up writ- ing nearly 40,000 words— almost an entire short novel!—of material that I didn’t directly use. Some of it was re cast and repurposed in different directions, and a lot of it was simply left to the side. The thing is when I throw something out of a book, I don’t just delete it. I put it into an “excise fi le” and keep it just in case it’ll come in handy later. Like now: I’ve taken vari ous bits from the excise fi le and with them have crafted a fi rst chapter of an alternate version of The Life of the Mind, the fi rst novella of The End of All Things. This version (roughly) covers the same events, with (roughly) the same characters, but with a substantially different narrative di- rection. -

Islam EXPOSED!

JACK VAN IMPE MINISTRIES JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2016 ISLAM EXPOSED! THE SHOCKING TRUTH now captured in the single strongest video Drs. Jack & Rexella Van Impe have ever produced! Don’t miss what’s insiDE: A REVELATION FROM DR. VAN IMPE, PAGE 3 FROM REXELLA’S HEART, PAGE 12 | LETTERS WE LOVE, PAGE 19 1. Can a democracy and 3. How has President Obama today for Christ’s return? ISLAM brings you answers Islam coexist? demonstrated anti-Israel and 6. What is “taqiyya” and how to these compelling 2. Does the Koran really tell pro-Muslim attitudes? does it contradict the Bible? questions: EXPOSED Muslims to kill those who 4. How is ISIS growing? 7. Who are the false prophets disagree with them? 5. How is the stage being set today, predicted in the Bible? And many more! How much danger The Shocking Truth are you and your family in because About Islam ... Finally of the advance of radical Islam in these latter days? EXPOSED! BLOCKBUSTER VIDEO REVEALS WHAT MAINSTREAM MEDIA WON’T TELL YOU! SEND A GIFT OF The single strongest $ 95 BY DR. JACK VAN IMPE and most important 24 uddenly, in studios and created video ever produced 100 major the single strongest by Drs. Jack & cities across video we have ever Islam Exposed America, the produced — not only Rexella Van Impe! DVD (DIEV) Running Time: billboards went the strongest, but also ISLAM EXPOSED 80 minutes CC up — proclaiming an the most important astonishing lie: that the ... and certainly the PROVES THAT Jesus of the Koran and most urgently needed THE JESUS OF the Jesus of the Holy by multitudes in these THE KORAN AND Bible are one in the same! latter days! What a falsehood! This critically important video, THE JESUS OF When I heard the news Islam Exposed, shines the blazing THE CHRISTIAN about this outrageous campaign spotlight of truth on the gross of deception, organized by a misrepresentations about Jesus in BIBLE ARE leading Muslim organization, the Koran. -

St.-Thomas-Aquinas-The-Summa-Contra-Gentiles.Pdf

The Catholic Primer’s Reference Series: OF GOD AND HIS CREATURES An Annotated Translation (With some Abridgement) of the SUMMA CONTRA GENTILES Of ST. THOMAS AQUINAS By JOSEPH RICKABY, S.J., Caution regarding printing: This document is over 721 pages in length, depending upon individual printer settings. The Catholic Primer Copyright Notice The contents of Of God and His Creatures: An Annotated Translation of The Summa Contra Gentiles of St Thomas Aquinas is in the public domain. However, this electronic version is copyrighted. © The Catholic Primer, 2005. All Rights Reserved. This electronic version may be distributed free of charge provided that the contents are not altered and this copyright notice is included with the distributed copy, provided that the following conditions are adhered to. This electronic document may not be offered in connection with any other document, product, promotion or other item that is sold, exchange for compensation of any type or manner, or used as a gift for contributions, including charitable contributions without the express consent of The Catholic Primer. Notwithstanding the preceding, if this product is transferred on CD-ROM, DVD, or other similar storage media, the transferor may charge for the cost of the media, reasonable shipping expenses, and may request, but not demand, an additional donation not to exceed US$25. Questions concerning this limited license should be directed to [email protected] . This document may not be distributed in print form without the prior consent of The Catholic Primer. Adobe®, Acrobat®, and Acrobat® Reader® are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated in the United States and/or other countries. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

Limits, Malice and the Immortal Hulk

https://lthj.qut.edu.au/ LAW, TECHNOLOGY AND HUMANS Volume 2 (2) 2020 https://doi.org/10.5204/lthj.1581 Before the Law: Limits, Malice and The Immortal Hulk Neal Curtis The University of Auckland, New Zealand Abstract This article uses Kafka's short story 'Before the Law' to offer a reading of Al Ewing's The Immortal Hulk. This is in turn used to explore our desire to encounter the Law understood as a form of completeness. The article differentiates between 'the Law' as completeness or limitlessness and 'the law' understood as limitation. The article also examines this desire to experience completeness or limitlessness in the work of George Bataille who argued such an experience was the path to sovereignty. In response it also considers Francois Flahault's critique of Bataille who argued Bataille failed to understand limitlessness is split between a 'good infinite' and a 'bad infinite', and that it is only the latter that can ultimately satisfy us. The article then proposes The Hulk, especially as presented in Al Ewing's The Immortal Hulk, is a study in where our desire for limitlessness can take us. Ultimately it proposes we turn ourselves away from the Law and towards the law that preserves and protects our incompleteness. Keywords: Law; sovereignty; comics; superheroes; The Hulk Introduction From Jean Bodin to Carl Schmitt, the foundation of the law, or what we more readily understand as sovereignty, is marked by a significant division. The law is a limit in the sense of determining what is permitted and what is proscribed, but the authority for this limit is often said to derive from something unlimited. -

Raising the Last Hope British Romanticism and The

RAISING THE LAST HOPE BRITISH ROMANTICISM AND THE RESURRECTION OF THE DEAD, 1780-1830 by DANIEL R. LARSON B.A., University of New Mexico, 2009 M.A., University of New Mexico, 2011 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English 2016 This thesis entitled: “Raising the Last Hope: British Romanticism and the Resurrection of the Dead, 1780-1830” written by Daniel Larson has been approved for the Department of English Jeffrey Cox Jill Heydt-Stevenson Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii ABSTRACT Larson, Daniel R. (Ph.D., English) Raising the Last Hope: British Romanticism and the Resurrection of the Dead, 1780-1830 Thesis directed by Professor Jeffrey N. Cox This dissertation examines the way the Christian doctrine of bodily resurrection surfaces in the literature of the British Romantic Movement, and investigates the ways literature recovers the politically subversive potential in theology. In the long eighteenth century, the orthodox Christian doctrine of bodily resurrection (historically, a doctrine that grounded believers’ resistance to state oppression) disappears from the Church of England’s theological and religious dialogues, replaced by a docile vision of disembodied life in heaven—an afterlife far more amenable to political power. However, the resurrection of the physical body resurfaces in literary works, where it can again carry a powerful resistance to the state. -

Dressing in American Telefantasy

Volume 5, Issue 2 September 2012 Stripping the Body in Contemporary Popular Media: the value of (un)dressing in American Telefantasy MANJREE KHAJANCHI, Independent Researcher ABSTRACT Research perspectives on identity and the relationship between dress and body have been frequently studied in recent years (Eicher and Roach-Higgins, 1992; Roach-Higgins and Eicher, 1992; Entwistle, 2003; Svendsen, 2006). This paper will make use of specific and detailed examples from the television programmes Once Upon a Time (2011- ), Falling Skies (2011- ), Fringe (2008- ) and Game of Thrones (2011- ) to discover the importance of dressing and accessorizing characters to create humanistic identities in Science Fiction and Fantastical universes. These shows are prime case studies of how the literal dressing and undressing of the body, as well as the aesthetic creation of television worlds (using dress as metaphor), influence perceptions of personhood within popular media programming. These four shows will be used to examine three themes in this paper: (1) dress and identity, (2) body and world transformations, and (3) (non-)humanness. The methodological framework of this article draws upon existing academic literature on dress and society, combined with textual analysis of the aforementioned Telefantasy shows, focussing primarily on the three themes previously mentioned. This article reveals the role transformations of the body and/or the world play in American Telefantasy, and also investigates how human and near-human characters and settings are fashioned. This will invariably raise questions about what it means to be human, what constitutes belonging to society, and the connection that dress has to both of these concepts. KEYWORDS Aesthetics, Body, Dress, Falling Skies, Fringe, Game of Thrones, Identity, Once Upon a Time, Telefantasy. -

Jack Van Impe's

JACK VAN IMPE MINISTRIES JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2015 FACING CHRISTIANITY IN THE 21ST CENTURY: FALSE PROPHETS, DAMNABLE HERESIES, AND DOCTRINES OF DEMONS NEW VIDEO TEACHING FROM DRS. JACK AND REXELLA VAN IMPE INSIDE Don’t miss what’s insiDE: A REVELATION FROM DR. VAN IMPE, PAGE 3 FROM REXELLA’S HEART, PAGE 12 | LETTERS WE LOVE, PAGE 19 They’re here! Prepare yourself and your family for the final signs and dangers facing Beware: Christianity in the 21st Century! FALSE PROPHETS DECEIVING CHRISTIANS New video teaching from TODAY! Drs. Jack and Rexella Van Impe helps you protect yourself and your family from the apostates and antichrists who claim to be speaking for Christ and the Church — but BY DR. JACK VAN IMPE are actually spewing heresies and lies! Get the answers you need to he Holy Spirit woke me both powerful and urgent. It could the critical questions like: at 4:30 in the morning — not be delayed. What if further enormous and I could do nothing illness prevented me from sharing compromise » Where is false prophecy rampant in the Church but obey. it with you, and with multitudes currently today? My doctors had warned globally? Or what if those who have inundating » Is it right to judge false me to stay in bed. I was threatened my life finally succeeded Christianity: prophets? recovering from successful in stopping or sidetracking my » How do I judge a false surgery, but I endured four ministry, and preventing me from BEWARE! prophet? days of significant pain, producing the video False Prophets, » How do I know if my church and I had been ordered which — I knew Damnable Heresies, and is apostate? to submit to complete instantly — must be Doctrines of Demons » When is it right to change bed-rest. -

Selections from the Apocalyptic Genre

Selections from the Apocalyptic Genre Supplement to Dances with Devils {original or earlier year of publication appears in these brackets} Commentaries on Revelation Robert Van Kampen, The Sign: Bible Prophesy Concerning the End Times, expanded edition (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, 1993 {1992}). Billy Graham, Approaching Hoofbeats: The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, (Minneapolis, MN: Grason, 1983), Jack Van Impe, Revelation Revealed: A Verse-by-Verse Study, revised, eighth printing, (Dallas: Word Publishing, 1996 {first printing 1982, revised 1992}). Tim LaHaye, Revelation: Illustrated and Made Plain, revised, (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervon, 1975 {first printing 1973}). Signs of the Times Prophecy William T. James, ed., Foreshocks of Antichrist; (Eugene, OR: Harvest House, 1997) Charles Halff, The End Times Are Here Now, (Springdale, PA: Whitaker House, 1997). William T. James, ed., Raging Into Apocalypse: Essays in Apocalypse IV, (Green Forest, AK: New Leaf Press, 1996). Contributors include Dave Breese, J.R. Church, Grant Jeffrey, David A. Lewis, Chuck Missler, Henry Morris, Gary Stearman, John Walvoord, and David F. Webber. Jack Van Impe, 2001: On the Edge of Eternity, (Dallas: Word Publishing, 1996) ' Grant R. Jeffrey, Apocalypse: The Coming Judgement of Nations, (New York: Bantam, 1994); reprint of original 1992 edition by Frontier Research Publications. [Milton] William Cooper, Behold a Pale Horse, (Sedona, AZ: Light Techology Publishing, 1991). David Allen Lewis, Prophecy 2000, (Green Forest, AK: New Leaf Press, 1990); eighth printing, expanded & revised, 1996). Grant R. Jeffrey, Armageddon: Appointment with Destiny, (New York: Bantam, 1990); reprint of original 1988 edition by Frontier Research Publications. Hal Lindsey Hal Lindsey, Apocalypse Code, (Palos Verdes, CA: Western Front, 1997). -

Preaching to the Converted: Making Responsible Evangelical Subjects Through Media by Holly Thomas a Thesis Submitted to the Facu

Preaching to the Converted: Making Responsible Evangelical Subjects Through Media By Holly Thomas A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2016, Holly Thomas Abstract This dissertation examines contemporary televangelist discourses in order to better articulate prevailing models of what constitutes ideal-type evangelical subjectivities and televangelist participation in an increasingly mediated religious landscape. My interest lies in apocalyptic belief systems that engage end time scenarios to inform understandings of salvation. Using a Foucauldian inspired theoretical-methodology shaped by discourse analysis, archaeology, and genealogy, I examine three popular American evangelists who represent a diverse array of programming content: Pat Robertson of the 700 Club, John Hagee of John Hagee Today, and Jack and Rexella Van Impe of Jack Van Impe Presents. I argue that contemporary evangelical media packages now cut across a variety of traditional and new technologies to create a seamless mediated empire of participatory salvation where believers have access to complementary evangelist products and messages twenty-four hours a day from a multitude of access points. For these reasons, I now refer to televangelism as mediated evangelism and televangelists as mediated evangelists while acknowledging that the televised programs still form the cornerstone of their mediated messages and engagement with believers. The discursive formations that take shape through this landscape of mediated evangelism contribute to an apocalyptically informed religious-political subjectivity that identifies civic and political engagement as an expected active choice and responsibility for attaining salvation, in line with other more obviously evangelical religious practices, like prayer, repentance, and acceptance of Jesus Christ as savior. -

Alcohol: the Beloved Enemy Prophecy

® JACK Contact JACK VAN IMPE MINISTRIES at Box 7004, Troy, Michigan 48007. In Canada: JACK VAN IMPE MINISTRIES OF CANADA® Box 1717, Postal Station A, Windsor, ON N9A 6Y1. For immediate attention, call us at (248) 852-5225 or fax (248) 852-2692. Thank you for your love and generosity ... and God bless you! VANIMPE MINISTRIES MAY/JUNE 2010 Visit our Web address at: www.jvim.com The mystery of iniquity ... ... the abomination of desolation ... ... the name and number of the beast ... it could all be revealed today! he dictator of the New World Order cannot come into his complete dominion until we believers have been called Thome in the twinkling of an eye, but all the other signs of his appearance are in place. You need to know the facts ... and now you can! In this breakthrough video, Drs. Jack and Rexella Van Impe: • identify the major events which must take place before the leader of the New World Order can be revealed, • illuminate the main characteristics the Bible predicts he must possess, and • explain the likelihood that he could come to power at any moment! Get this video and make sure all your friends and family members understand the evil that this leader will soon unleash — that can only be avoided by choosing Christ as Savior. Dictator of the New World Order: Alive and Waiting A video drama that’s the perfect in the Wings DVD (DALV) prophetic witnessing resource — Don’t miss what’s inside Dictator of the New World Order: Alive and Waiting A revelation from Dr.Van Impe ......page 3 in the Wings VHS (VALV) and absolutely crucial to you and From Rexella’s heart.....................page 12 Send a gift of $24.95 your family Letters We Love ..............................page 27 Running Time: 105 minutes CC People from all generations need to know ..