The Third Offset: the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cross-References ASTEROID IMPACT Definition and Introduction History of Impact Cratering Studies

18 ASTEROID IMPACT Tedesco, E. F., Noah, P. V., Noah, M., and Price, S. D., 2002. The identification and confirmation of impact structures on supplemental IRAS minor planet survey. The Astronomical Earth were developed: (a) crater morphology, (b) geo- 123 – Journal, , 1056 1085. physical anomalies, (c) evidence for shock metamor- Tholen, D. J., and Barucci, M. A., 1989. Asteroid taxonomy. In Binzel, R. P., Gehrels, T., and Matthews, M. S. (eds.), phism, and (d) the presence of meteorites or geochemical Asteroids II. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, pp. 298–315. evidence for traces of the meteoritic projectile – of which Yeomans, D., and Baalke, R., 2009. Near Earth Object Program. only (c) and (d) can provide confirming evidence. Remote Available from World Wide Web: http://neo.jpl.nasa.gov/ sensing, including morphological observations, as well programs. as geophysical studies, cannot provide confirming evi- dence – which requires the study of actual rock samples. Cross-references Impacts influenced the geological and biological evolu- tion of our own planet; the best known example is the link Albedo between the 200-km-diameter Chicxulub impact structure Asteroid Impact Asteroid Impact Mitigation in Mexico and the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary. Under- Asteroid Impact Prediction standing impact structures, their formation processes, Torino Scale and their consequences should be of interest not only to Earth and planetary scientists, but also to society in general. ASTEROID IMPACT History of impact cratering studies In the geological sciences, it has only recently been recog- Christian Koeberl nized how important the process of impact cratering is on Natural History Museum, Vienna, Austria a planetary scale. -

Massive Retaliation Charles Wilson, Neil Mcelroy, and Thomas Gates 1953-1961

Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of MassiveSEPTEMBER Retaliation 2012 Evolution of the Secretary OF Defense IN THE ERA OF Massive Retaliation Charles Wilson, Neil McElroy, and Thomas Gates 1953-1961 Special Study 3 Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation Charles Wilson, Neil McElroy, and Thomas Gates 1953-1961 Cover Photos: Charles Wilson, Neil McElroy, Thomas Gates, Jr. Source: Official DoD Photo Library, used with permission. Cover Design: OSD Graphics, Pentagon. Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation Evolution of the Secretary OF Defense IN THE ERA OF Massive Retaliation Charles Wilson, Neil McElroy, and Thomas Gates 1953-1961 Special Study 3 Series Editors Erin R. Mahan, Ph.D. Chief Historian, Office of the Secretary of Defense Jeffrey A. Larsen, Ph.D. President, Larsen Consulting Group Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense September 2012 ii iii Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation Contents Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Defense, the Historical Office of the Office of Foreword..........................................vii the Secretary of Defense, Larsen Consulting Group, or any other agency of the Federal Government. Executive Summary...................................ix Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. -

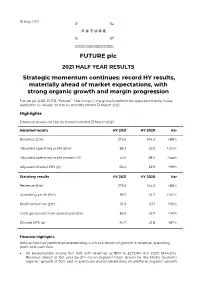

Rns Over the Long Term and Critical to Enabling This Is Continued Investment in Our Technology and People, a Capital Allocation Priority

19 May 2021 FUTURE plc 2021 HALF YEAR RESULTS Strategic momentum continues: record HY results, materially ahead of market expectations, with strong organic growth and margin progression Future plc (LSE: FUTR, “Future”, “the Group”), the global platform for specialist media, today publishes its results for the six months ended 31 March 2021. Highlights Financial results for the six months ended 31 March 2021 Adjusted results HY 2021 HY 2020 Var Revenue (£m) 272.6 144.3 +89% Adjusted operating profit (£m)1 89.2 39.9 +124% Adjusted operating profit margin (%) 33% 28% +5ppt Adjusted diluted EPS (p) 65.4 32.9 +99% Statutory results HY 2021 HY 2020 Var Revenue (£m) 272.6 144.3 +89% Operating profit (£m) 59.7 24.7 +142% Profit before tax (£m) 56.9 27.1 +110% Cash generated from operations (£m) 85.9 35.7 +141% Diluted EPS (p) 40.7 21.8 +87% Financial highlights Robust first-half performance extending our track record of growth in revenue, operating profit and cash flow: An exceptionally strong first half, with revenue up 89% to £272.6m (HY 2020: £144.3m). Revenue ahead of last year by 21% on an organic2 basis, driven by the Media division’s organic2 growth of 30% and in particular digital advertising on-platform organic2 growth of 30% and eCommerce affiliates’ organic2 growth of 56%. US achieved revenue growth of 31% on an organic2 basis and UK revenues grew by 5% organically (UK has a higher mix of events and magazines revenues which were impacted more materially by the pandemic). -

Mss Leupnittg Llrraui U.S., North Viet Set Paris As Site for Talks on Peace

THURSDAY, MAY 2, 1068 Avetuta Dally Net PNaa Run r m n t w e n t y For The Week EedeB The Weather £«pnitt0 HmUi April t t , 1N8 CHoudy tonlgM end tomotrow Pfc. John R. Caine, son of May Day Theme lEupnittg llrraUi with showers likely. (Low to Aboilt Town Mr. find Mrs. Frank Caine of 15,020 night in 40s. Totnorrow 00 to 94 Chambers St., is serving with NATIONAL PAVING 00. Manchester 4 City of Village Charm 60. Th« property «nd lighting com Battery I, 29th Artillery, in O f B entley F air mittees of the Manchester Com Vietnam, J 12 M A IN ST. TA lCO T TV R iC . C O N N . VOL. LXXXVH, NO. 182 (TWENTY-EIGHT PAGES—TWO SECTIONS) munity Playera will meet Sun Miss Arline Evans Shennihg ’’Once upon a May Day” is MANCHESTER, CONN., FRIDAY, MAY 3, 1968 (Oleeelfled Advertleing on Fege *8) PRICE TEN CENTS day at 2 p.m. at the home of the theme for the Bentley School The B0-«0 Club of St. Mary’s and Ronald Paul Lewis, both of Mrs. Harold Bonham, SB Amott PTA Fair, to be held at the DWVeWAYS-^ARKING AREAS Episooipal' Church will have its Manchester, were united in Rd. The. group’s forthcoming school Saturday, May 20, from DEVELOPMENT WORK final supper of the season and marriage Saturday afternoon at 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. Co-chairmen production, "Period of Adjust eteaOon of officers tomorrow ment,” will be discussed. The South Methodist Church. are Mrs. -

Winning the Salvo Competition Rebalancing America’S Air and Missile Defenses

WINNING THE SALVO COMPETITION REBALANCING AMERICA’S AIR AND MISSILE DEFENSES MARK GUNZINGER BRYAN CLARK WINNING THE SALVO COMPETITION REBALANCING AMERICA’S AIR AND MISSILE DEFENSES MARK GUNZINGER BRYAN CLARK 2016 ABOUT THE CENTER FOR STRATEGIC AND BUDGETARY ASSESSMENTS (CSBA) The Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments is an independent, nonpartisan policy research institute established to promote innovative thinking and debate about national security strategy and investment options. CSBA’s analysis focuses on key questions related to existing and emerging threats to U.S. national security, and its goal is to enable policymakers to make informed decisions on matters of strategy, security policy, and resource allocation. ©2016 Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. All rights reserved. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Mark Gunzinger is a Senior Fellow at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. Mr. Gunzinger has served as the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Forces Transformation and Resources. A retired Air Force Colonel and Command Pilot, he joined the Office of the Secretary of Defense in 2004. Mark was appointed to the Senior Executive Service and served as Principal Director of the Department’s central staff for the 2005–2006 Quadrennial Defense Review. Following the QDR, he served as Director for Defense Transformation, Force Planning and Resources on the National Security Council staff. Mr. Gunzinger holds an M.S. in National Security Strategy from the National War College, a Master of Airpower Art and Science degree from the School of Advanced Air and Space Studies, a Master of Public Administration from Central Michigan University, and a B.S. in chemistry from the United States Air Force Academy. -

Using a Nuclear Explosive Device for Planetary Defense Against an Incoming Asteroid

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2019 Exoatmospheric Plowshares: Using a Nuclear Explosive Device for Planetary Defense Against an Incoming Asteroid David A. Koplow Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/2197 https://ssrn.com/abstract=3229382 UCLA Journal of International Law & Foreign Affairs, Spring 2019, Issue 1, 76. This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Air and Space Law Commons, International Law Commons, Law and Philosophy Commons, and the National Security Law Commons EXOATMOSPHERIC PLOWSHARES: USING A NUCLEAR EXPLOSIVE DEVICE FOR PLANETARY DEFENSE AGAINST AN INCOMING ASTEROID DavidA. Koplow* "They shall bear their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks" Isaiah 2:4 ABSTRACT What should be done if we suddenly discover a large asteroid on a collision course with Earth? The consequences of an impact could be enormous-scientists believe thatsuch a strike 60 million years ago led to the extinction of the dinosaurs, and something ofsimilar magnitude could happen again. Although no such extraterrestrialthreat now looms on the horizon, astronomers concede that they cannot detect all the potentially hazardous * Professor of Law, Georgetown University Law Center. The author gratefully acknowledges the valuable comments from the following experts, colleagues and friends who reviewed prior drafts of this manuscript: Hope M. Babcock, Michael R. Cannon, Pierce Corden, Thomas Graham, Jr., Henry R. Hertzfeld, Edward M. -

Aviation Week & Space Technology

STARTS AFTER PAGE 34 Using AI To Boost How Emirates Is Extending ATM Efficiency Maintenance Intervals ™ $14.95 JANUARY 13-26, 2020 2020 THE YEAR OF SUSTAINABILITY RICH MEDIA EXCLUSIVE Digital Edition Copyright Notice The content contained in this digital edition (“Digital Material”), as well as its selection and arrangement, is owned by Informa. and its affiliated companies, licensors, and suppliers, and is protected by their respective copyright, trademark and other proprietary rights. Upon payment of the subscription price, if applicable, you are hereby authorized to view, download, copy, and print Digital Material solely for your own personal, non-commercial use, provided that by doing any of the foregoing, you acknowledge that (i) you do not and will not acquire any ownership rights of any kind in the Digital Material or any portion thereof, (ii) you must preserve all copyright and other proprietary notices included in any downloaded Digital Material, and (iii) you must comply in all respects with the use restrictions set forth below and in the Informa Privacy Policy and the Informa Terms of Use (the “Use Restrictions”), each of which is hereby incorporated by reference. Any use not in accordance with, and any failure to comply fully with, the Use Restrictions is expressly prohibited by law, and may result in severe civil and criminal penalties. Violators will be prosecuted to the maximum possible extent. You may not modify, publish, license, transmit (including by way of email, facsimile or other electronic means), transfer, sell, reproduce (including by copying or posting on any network computer), create derivative works from, display, store, or in any way exploit, broadcast, disseminate or distribute, in any format or media of any kind, any of the Digital Material, in whole or in part, without the express prior written consent of Informa. -

How Should the United States Confront Soviet Communist Expansionism? DWIGHT D

Advise the President: DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER How Should the United States Confront Soviet Communist Expansionism? DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER Advise the President: DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER Place: The Oval Office, the White House Time: May 1953 The President is in the early months of his first term and he recognizes Soviet military aggression and the How Should the subsequent spread of Communism as the greatest threat to the security of the nation. However, the current costs United States of fighting Communism are skyrocketing, presenting a Confront Soviet significant threat to the nation’s economic well-being. President Eisenhower is concerned that the costs are not Communist sustainable over the long term but he believes that the spread of Communism must be stopped. Expansionism? On May 8, 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower has called a meeting in the Solarium of the White House with Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and Treasury Secretary George M. Humphrey. The President believes that the best way to craft a national policy in a democracy is to bring people together to assess the options. In this meeting the President makes a proposal based on his personal decision-making process—one that is grounded in exhaustive fact gathering, an open airing of the full range of viewpoints, and his faith in the clarifying qualities of energetic debate. Why not, he suggests, bring together teams of “bright young fellows,” charged with the mission to fully vet all viable policy alternatives? He envisions a culminating presentation in which each team will vigorously advocate for a particular option before the National Security Council. -

DOUBLE COUPONS Ralb

20 - MANCHESTER HERALD. Sat., March 12. i9H3 She remembers when ‘prodigies' all were boys working In a post office." !; PAWTUCKET, R.I. ers are gifted kids who Now she discusses the ness. High intellectual Depending on what But it is hard drawing a than most school criteria you use, from 1 to complete picture of a programs. She thinks many pro^s (UPI) — When Deidre have grown up and not fit gifted before various capacity with an IQ of 130 grams for the gifted in . Lovecky was growing up the mold,” she said. groups. But even at that usually is a standard. 5 percent of the population gifted child. Her favorite example is “There are a lot of Albert Einstein, a poor today’s schoois probably.; in North Tarry town, N.Y., Deirdre Lovecky came she was nervous about Other standards are high is gifted. would never pick Einstein ; her family used to call her to Rhode Island to intern being interviewed for the academic achievement in Most parents,' she different ways of being student and a daydrea- thinks, know if their child average, a lot different mer, who related poorly to for special attention. '■ cousin a genius. Yet Dei in child psychology at first time a picked apart a one or more areas, excep "If he were assesset} 1 dre knew she was brighter Bradley Hospital in East styrofoam cup as she tional leadership ability is gifted. Such children ways of being gifted,” other children and spent a Providence. She found or creativity and talent in ask incisive questions Lovecky said. -

The Merchants of Death

THE MERCHANTS OF DEATH The Military-Industrial Complex and the Influence on Democracy Name: Miriam Collaris Student number: 387332 Erasmus University Rotterdam Master thesis: Global History & International Relations Supervisor: Prof. Wubs Date: June 12th, 2016 Merchants of Death Miriam Collaris Erasmus University Rotterdam June 12, 2016 PREFACE This is a thesis about the Military-industrial Complex in the United States of America, a subject, which has been widely discussed in the 1960s, but has moved to the background lately. I got inspired by this subject through an internship I have done in Paris in 2012. Here I was working for an event agency that organized business conventions for the defense and security sector, and in particular the aerospace industry. This was the first time I got in touch with this defense industry and this was the first moment that I realized how much money is involved in this sector. Warfare turned out to be real business. At the conventions enormous stands emerged with the most advanced combat vehicles and weaponry. These events were focused on matchmaking between various players in this sector. Hence, commercial deals were made between government agencies and the industry, which was very normal and nobody questioned this. When I read about this Military-industrial Complex, years later, I started to think about these commercial deals between government and industry and the profits that were gained. The realization that war is associated with profits, interested me in such a way that I decided to write my master -

BATTLE-SCARRED and DIRTY: US ARMY TACTICAL LEADERSHIP in the MEDITERRANEAN THEATER, 1942-1943 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial

BATTLE-SCARRED AND DIRTY: US ARMY TACTICAL LEADERSHIP IN THE MEDITERRANEAN THEATER, 1942-1943 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Steven Thomas Barry Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Allan R. Millett, Adviser Dr. John F. Guilmartin Dr. John L. Brooke Copyright by Steven T. Barry 2011 Abstract Throughout the North African and Sicilian campaigns of World War II, the battalion leadership exercised by United States regular army officers provided the essential component that contributed to battlefield success and combat effectiveness despite deficiencies in equipment, organization, mobilization, and inadequate operational leadership. Essentially, without the regular army battalion leaders, US units could not have functioned tactically early in the war. For both Operations TORCH and HUSKY, the US Army did not possess the leadership or staffs at the corps level to consistently coordinate combined arms maneuver with air and sea power. The battalion leadership brought discipline, maturity, experience, and the ability to translate common operational guidance into tactical reality. Many US officers shared the same ―Old Army‖ skill sets in their early career. Across the Army in the 1930s, these officers developed familiarity with the systems and doctrine that would prove crucial in the combined arms operations of the Second World War. The battalion tactical leadership overcame lackluster operational and strategic guidance and other significant handicaps to execute the first Mediterranean Theater of Operations campaigns. Three sets of factors shaped this pivotal group of men. First, all of these officers were shaped by pre-war experiences. -

Air & Space Power Journal

AIR & SPACE POWER JOURNAL, Winter 2018 AIR & SPACE WINTER 2018 Volume 32, No. 4 A Model of Air Force Squadron Vitality Maj Gen Stephen L. Davis, USAF Dr. William W. Casey Wars of Cognition How Clausewitz and Neuroscience Influence Future War-Fighter Readiness Maj Michael J. Cheatham, USAF Seize the Highest Hill A Call to Action for Space-Based Air Surveillance Lt Col Troy McLain, USAF Lt Col Gerrit Dalman, USAF The Long-Range Standoff Cruise Missile A Key Component of the Triad Dr. Dennis Evans Dr. Jonathan Schwalbe Science and Technology Enablers of Live Virtual Constructive Training in the Air Domain Dr. Christopher Best, Defence Science and Technology Group FLTLT Benjamin Rice, Royal Australian Air Force WINTER 2018 Volume 32, No. 4 AFRP 10-1 Senior Leader Perspective A Model of Air Force Squadron Vitality ❙ 4 Maj Gen Stephen L. Davis, USAF Dr. William W. Casey Features Wars of Cognition: How Clausewitz and Neuroscience Influence Future War-Fighter Readiness ❙ 16 Maj Michael J. Cheatham, USAF Seize the Highest Hill: A Call to Action for Space-Based Air Surveillance ❙ 31 Lt Col Troy McLain, USAF Lt Col Gerrit Dalman, USAF The Long-Range Standoff Cruise Missile: A Key Component of the Triad ❙ 47 Dr. Dennis Evans Dr. Jonathan Schwalbe Science and Technology Enablers of Live Virtual Constructive Training in the Air Domain ❙ 59 Dr. Christopher Best, Defence Science and Technology Group FLTLT Benjamin Rice, Royal Australian Air Force Departments 74 ❙ Views Operation Vengeance: Still Offering Lessons after 75 Years ❙ 74 Lt Col Scott C. Martin, USAF Three Competing Options for Acquiring Innovation ❙ 85 Lt Col Daniel E.