Examining Greengairs and Ravenscraig

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identification of Pressures and Impacts Arising Frm Strategic Development

Report for Scottish Environment Protection Agency/ Neil Deasley Planning and European Affairs Manager Scottish Natural Heritage Scottish Environment Protection Agency Erskine Court The Castle Business Park Identification of Pressures and Impacts Stirling FK9 4TR Arising From Strategic Development Proposed in National Planning Policy Main Contributors and Development Plans Andrew Smith John Pomfret Geoff Bodley Neil Thurston Final Report Anna Cohen Paul Salmon March 2004 Kate Grimsditch Entec UK Limited Issued by ……………………………………………… Andrew Smith Approved by ……………………………………………… John Pomfret Entec UK Limited 6/7 Newton Terrace Glasgow G3 7PJ Scotland Tel: +44 (0) 141 222 1200 Fax: +44 (0) 141 222 1210 Certificate No. FS 13881 Certificate No. EMS 69090 09330 h:\common\environmental current projects\09330 - sepa strategic planning study\c000\final report.doc In accordance with an environmentally responsible approach, this document is printed on recycled paper produced from 100% post-consumer waste or TCF (totally chlorine free) paper COMMISSIONED REPORT Summary Report No: Contractor : Entec UK Ltd BACKGROUND The work was commissioned jointly by SEPA and SNH. The project sought to identify potential pressures and impacts on Scottish Water bodies as a consequence of land use proposals within the current suite of Scottish development Plans and other published strategy documents. The report forms part of the background information being collected by SEPA for the River Basin Characterisation Report in relation to the Water Framework Directive. The project will assist SNH’s environmental audit work by providing an overview of trends in strategic development across Scotland. MAIN FINDINGS Development plans post 1998 were reviewed to ensure up-to-date and relevant information. -

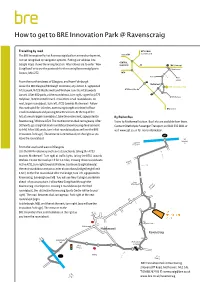

How to Get to BRE Innovation Park @ Ravenscraig

How to get to BRE Innovation Park @ Ravenscraig Travelling by road M73 / M80 Airport M8 Cumbernauld The BRE Innovation Park at Ravenscraig is built on a new development, not yet recognised by navigation systems. Putting our address into CENTRAL Google maps shows the wrong location. Alternatives are to enter New GLASGOW A8 6 M8 Edinburgh Craig or to use the postcode for the nearby Ravenscraig Sports Newhouse ‘oad M74 Centre , ML1 2TZ. Bellshill A73 Lanark From the north and east of Glasgow, and from Edinburgh 5 Motherwell Leave the M8 Glasgow/Edinburgh motorway at junction 6, signposted BRE Innovation Park A73 Lanark /A723 Motherwell and Wishaw. Join the A73 towards A725 East Kilbride Lanark. After 400 yards, at the roundabout, turn right, signed to A775 6 A721 Wishaw Holytown /A723 to Motherwell. Cross three small roundabouts. At next, larger roundabout, turn left, A723 towards Motherwell. Follow this road uphill for 1.6 miles, continuing straight on at each of four M74 Carlisle small roundabouts and passing New Stevenson. At the top of the hill, at a much larger roundabout, take the second exit, signposted to By Rail or Bus Ravenscraig / Wishaw A721. The road becomes dual carriageway. After Trains to Motherwell station. Bus links are available from there. 300 yards, go straight at next roundabout (new housing development Contact Strathclyde Passenger Transport on 0141 332 6811 or to left). After 500 yards, turn left at roundabout (you will see the BRE visit www.spt.co.uk for more information. Innovation Park sign). The entrance is immediately on the right as you J6 leave the roundabout. -

FCC Environment Corporate Social Responsibility Report 2015 Contents 16 08 People Focus Who We Are

from waste to resource FCC Environment Corporate Social Responsibility Report 2015 Contents 16 08 People focus Who we are 32 Doing the right thing 04 06 Foreword from What we do 10 Paul Taylor Highlights and challenges 2 — 3 FCC Corporate Social Responsibility Report Introduction Doing the right thing 04 Foreword 33 Integrated Management System 06 What we do 34 Contributing to communities 08 Who we are Forward thinking Highlights and challenges 39 Introduction 11 Contract wins and renewals 41 Industry opinion 13 Infrastructure investments Appendix People focus 42 Appendix 1: 17 Health and safety Waste management methods 20 Equality and diversity 43 Appendix 2: 22 Competence Carbon emissions Management System 23 ABCD Awards Environmental commitment 25 Regulatory compliance 26 Reducing our energy use 28 Land restoration 30 Energy crops 24 Environmental commitment 38 Forward thinking Foreword As one of the UK’s largest waste management and recycling businesses, our corporate social responsibility is a meaningful gauge of FCC Environment’s sustainability. Over the last five years we have Will demand curtail, or will increased We look ahead to the future with transformed our safety culture, recycling to meet the demands of the enthusiasm, despite the uncertainties improved our standards of working, Circular Economy Package mean our we face: not least the British made strategic investments in European neighbours need more fuel referendum on EU membership; infrastructure, supported local to keep their lights on? the possible adoption of the communities, developed new revenue Circular Economy package; and In the meantime, we continue to look streams and significantly reduced its undetermined impacts on the ahead and provide leadership in the the environmental impacts of our marketplace. -

LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN MODIFIED PROPOSED PLAN POLICY DOCUMENT Local Development Plan Modified Proposed Plan Policy Document 2018

LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN MODIFIED PROPOSED PLAN POLICY DOCUMENT Local Development Plan Modified Proposed Plan Policy Document 2018 photo 2 Councillor Harry Curran, Planning Committee Convener The Local Development Plan sets out the Policies and Proposals to guide and meet North Lanarkshire’s development needs over the next 5-10 year. We want North Lanarkshire to be a place where The Local Development Plan policies identify the Through this Plan we will seek to ensure that the right everyone is given equality of opportunity, where development sites we need for sustainable and amount of development happens in the right places, individuals are supported, encouraged and cared for inclusive economic growth, sites we need to in a way that balances supply and demand for land at each key stage of their life. protect and enhance and has a more focussed uses, helps places have the infrastructure they need policy structure that sets out a clear vision for North without compromising the environment that defines North Lanarkshire is already a successful place, Lanarkshire as a place. Our Policies ensure that the them and makes North Lanarkshire a distinctive and making a significant contribution to the economy development of sites is appropriate in scale and successful place where people want to live, learn, of Glasgow City Region and Scotland. Our Shared character, will benefit our communities and safeguard work, invest and visit. Ambition, delivered through this Plan and our our environment. Economic Regeneration Delivery Plan, is to make it even more successful and we will continue to work with our partners and communities to deliver this Ambition. -

Local Landscape Character Assessment Background Report

NORTH LANARKSHIRE LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN MODIFIED PROPOSED PLAN LOCAL LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT BACKGROUND REPORT NOVEMBER 2018 North Lanarkshire Council Enterprise and Communities CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. URS Review of North Lanarkshire Local Landscape Character (2015) 3. Kilsyth Hills Special Landscape Area (SLA) 4. Clyde Valley Special Landscape Area (SLA) Appendices Appendix 1 - URS Review of North Lanarkshire Local Landscape Character (2015) 1. Introduction 1.1 Landscape designations play an important role in Scottish Planning Policy by protecting and enhancing areas of particular value. Scottish Planning Policy encourages local, non-statutory designations to protect and create an understanding of the role of locally important landscape have on communities. 1.2 In 2014, as part of the preparation of the North Lanarkshire Local Development Proposed Plan, a review of local landscape designations was undertaken by URS as part of wider action for landscape protection and management. 2. URS Review of North Lanarkshire Local Landscape Character (2015) 2.1 The purpose of the Review was to identify and provide an awareness of the special character and qualities of the designated landscape in North Lanarkshire and to contribute to guiding appropriate future development to the most appropriate locations. The Review has identified a number of Local Landscape Units (LLU) that are of notable quality and value within which future development requires careful consideration to avoid potential significant impact on their landscape character. 2.2 There are two exemplar LLUs identified in this study, Kilsyth Hills and Clyde Valley, which are seen as very sensitive to development. Both of these areas warrant specific recognition and protection, as their high landscape quality would be threatened and adversely affected by unsympathetic development within their boundaries. -

Greater Glasgow & the Clyde Valley

What to See & Do 2013-14 Explore: Greater Glasgow & The Clyde Valley Mòr-roinn Ghlaschu & Gleann Chluaidh Stylish City Inspiring Attractions Discover Mackintosh www.visitscotland.com/glasgow Welcome to... Greater Glasgow & The Clyde Valley Mòr-roinn Ghlaschu & Gleann Chluaidh 01 06 08 12 Disclaimer VisitScotland has published this guide in good faith to reflect information submitted to it by the proprietor/managers of the premises listed who have paid for their entries to be included. Although VisitScotland has taken reasonable steps to confirm the information contained in the guide at the time of going to press, it cannot guarantee that the information published is and remains accurate. Accordingly, VisitScotland recommends that all information is checked with the proprietor/manager of the business to ensure that the facilities, cost and all other aspects of the premises are satisfactory. VisitScotland accepts no responsibility for any error or misrepresentation contained in the guide and excludes all liability for loss or damage caused by any reliance placed on the information contained in the guide. VisitScotland also cannot accept any liability for loss caused by the bankruptcy, or liquidation, or insolvency, or cessation of trade of any company, firm or individual contained in this guide. Quality Assurance awards are correct as of December 2012. Rodin’s “The Thinker” For information on accommodation and things to see and do, go to www.visitscotland.com at the Burrell Collection www.visitscotland.com/glasgow Contents 02 Glasgow: Scotland with style 04 Beyond the city 06 Charles Rennie Mackintosh 08 The natural side 10 Explore more 12 Where legends come to life 14 VisitScotland Information Centres 15 Quality Assurance 02 16 Practical information 17 How to read the listings Discover a region that offers exciting possibilities 17 Great days out – Places to Visit 34 Shopping every day. -

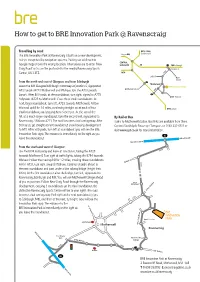

How to Get to BRE Innovation Park @ Ravenscraig

How to get to BRE Innovation Park @ Ravenscraig Travelling by road M73 / M80 Cumbernauld The BRE Innovation Park at Ravenscraig is built on a new development, Airport M8 not yet recognised by navigation systems. Putting our address into CENTRAL Google maps shows the wrong location. Alternatives are to enter ‘New GLASGOW A8 6 M8 Edinburgh Craig Road’ or to use the postcode for the nearby Ravenscraig Sports Newhouse M74 Centre , ML1 2TZ. A775 Bellshill A73 Lanark From the north and east of Glasgow, and from Edinburgh 5 Motherwell Leave the M8 Glasgow/Edinburgh motorway at junction 6, signposted BRE Innovation Park A725 East Kilbride A73 Lanark /A723 Motherwell and Wishaw. Join the A73 towards A723 Lanark. After 400 yards, at the roundabout, turn right, signed to A775 6 A721 Wishaw Holytown /A723 to Motherwell. Cross three small roundabouts. At next, larger roundabout, turn left, A723 towards Motherwell. Follow this road uphill for 1.6 miles, continuing straight on at each of four M74 Carlisle small roundabouts and passing New Stevenson. At the top of the hill, at a much larger roundabout, take the second exit, signposted to By Rail or Bus Ravenscraig / Wishaw A721. The road becomes dual carriageway. After Trains to Motherwell station. Bus links are available from there. 300 yards, go straight at next roundabout (new housing development Contact Strathclyde Passenger Transport on 0141 332 6811 or to left). After 500 yards, turn left at roundabout (you will see the BRE visit www.spt.co.uk for more information. Innovation Park sign). The entrance is immediately on the right as you J6 leave the roundabout. -

Ravenscraig Lanarkshire Vaccination Centre Motherwell Railway Station

Ref. NHSRC1/03/2021 Route Map Service VAC 1 Whilst every effort will be made to adhere to the scheduled times, the Partnership disclaims any liability in respect of loss or inconvenience arising from any failure to operate journeys as published, changes in timings or printing Bus Timetable errors. From 11 March 2021 A723 Merry Street For more information please visit spt.co.uk. or alternatively, for all public transport enquiries, call: Motherwell Railway Ravenscraig Station Lanarkshire Vaccination Centre A721 Windmillhill Street If you have any comments or suggestions This service is operated by about the service(s) provided please United Coaches on behalf of contact: NHS Lanarkshire and SPT SPT United Coaches Ltd. Bus Operations 108 High Street 131 St. Vincent St Newarthill Glasgow G2 5JF Motherwell Available to passengers for travel ML1 5JH wholly to or from the Vaccination t 0345 271 2405 Centre at Ravenscraig Sports t 0141 333 3690 t 01698 200 166 Centre e [email protected] Service Vac 1 Motherwell Train Station – Ravenscraig Vaccination Centre Circular Operated by United Coaches Ltd on behalf of NHS Lanarkshire and SPT Route Service Vac 1: From Motherwell Station, Muir Street via A721 Hope Street, Menteith Road, A723 Merry St, Ravenscraig Spine Rd, New Craig Road, O'Donnell Way, NHS Ravenscraig regional Sports Facility Vaccination Centre, circle roundabout continue O'Donnel Way, Robberhall Road, A721 Craigneuk St, Windmillhill St, Brandon Street, A721, West Hamilton St, Hamilton Road to Motherwell Station, Muir Street. Monday to Sunday -

FOR SALE Incorporating a Wide Variety of Uses Which Interlink Comprehensive Scheme Including: and Complement Each Other

Ravenscraig has been carefully master planned Once completed, Ravenscraig will comprise a FOR SALE incorporating a wide variety of uses which interlink comprehensive scheme including: and complement each other. • Around 3,500 new homes with two new schools Plots have been designed to be flexible to • A new town centre with 84,000 sq m of retail and RAVENSCRAIG accommodate a wide range of uses to suit a leisure space with access to a new railway station diverse range of large and small businesses. • Up to 216,000 sq m of business and industrial space Plots are available for immediate development. • Major parkland areas DEVELOPMENT SITES • A new transport network linking the M74 and M8 PLOTS OF UP TO 100 ACRES RAVENSCRAIG REGIONAL SPORTS FACILITY NEW CRAIG ROAD NEW COLLEGE LANARKSHIRE MOTHERWELL CAMPUS Location Ravenscraig is situated in one of the most accessible parts of Scotland, with over two thirds of Scotland’s population within 90 minutes drive time. Located in North Lanarkshire, at the heart of Scotland’s Central Belt, Ravenscraig borders the existing towns of Wishaw and Motherwell, which combined have a population of over 60,000. Lanarkshire boasts a thriving network of new and historic towns and villages, many of the country’s top tourist attractions, including a World Heritage Site, and some of the world’s biggest firms. B RAVENSCRAIG REGIONAL A SPORTS FACILITY C D NEW CRAIG ROAD E NEW COLLEGE LANARKSHIRE MOTHERWELL CAMPUS Master Plan MARSTON’S FAMILY PUB POTENTIAL HOTEL DEVELOPMENT RAVENSCRAIG REGIONAL SPORTS B CENTRE POSSIBLE A FOOD STORE SITE POSSIBLE RETAIL SITE C D E NEW COLLEGE LANARKSHIRE F BUSINESS AND COMMERCIAL PROPERTY Proposed Ravenscraig will be an attractive location for business – for investors, occupiers and employees – and has outline planning consent for up to 216,000 sq m (2,325,000 sq ft) of business and industrial space. -

FCC Group 2020 Sustainability Report

FCC Group 2020 Sustainability Report FCC Group non-financial information report, in compliance with Law 11/2018 on non-financial information and diversity PROTECTING BIODIVERSITY........................................................................................................................ 80 8. Committed to the FCC Group Human Resources team ............................................................................................ 82 THE DNA OF THE HUMAN RESOURCES TEAM IN THE FCC GROUP ....................................................... 82 THE PEOPLE IN THE CENTRE: YOU_ .......................................................................................................... 83 HUMAN CAPITAL PROFILE ............................................................................................................................ 83 8.3.1 Diversity in the workforce ............................................................................................................................. 83 8.3.2 Organisational structure ............................................................................................................................... 85 8.3.3 Appreciation of job positions ........................................................................................................................ 85 8.3.4 Recruitment and dismissals ......................................................................................................................... 85 COMMITMENT TO TALENT ........................................................................................................................... -

Ravenscraig Regional Sports Facility Directions & Maps

Ravenscraig Regional Sports Facility Directions & Maps Item Detail Note Address Ravenscraig Sports Facility www.nlleisure.co.uk O’Donnell Way Ravenscraig Motherwell ML1 1AD John Swanson, Facilities Manager, 01698 274631 Alan Airlie, Assistant Facilities Manager, 01698 274635 Louise Miller, Administration Supervisor, 01698 274634 Ken Walker 01698 2746?? Distance and times for Glasgow - 17 miles (25 minutes #1) major population Edinburgh - 41 miles (1 hour, 2 minutes #1) centres Stirling - 35 miles (45 minutes #1) Inverness - 175 miles (4 hours #1) Manchester - 204 miles (3 hours, 37 minutes #1) London - 398 miles (7 hours, 3 minutes #1) Train Links Nearest Main Line Station www.nationalrail.co.uk/stations/mth/details.html Motherwell Train Station – 2.18 miles (7 minutes #1) Rail time to London is between 4-6 hours depending on service chosen Muir Street, Motherwell, North Lanarkshire, ML1 3LA Airports Glasgow International Airport – 26 miles (35 minutes www.glasgowairport.com #1) Tel: +44 (0)844 481 5555 Flying time to London is just over 1 hour. Glasgow Airport, Paisley, Renfrewshire, Scotland, PA3 2SW Item Detail Note Edinburgh International Airport – 31.26 miles (49 www.edinburghairport.com minutes #1) General enquiries Flying time to London is just over 1 hour. Tel: +44 (0)844 481 8989 Edinburgh Airport, Scotland, United Kingdom, EH12 9DN Glasgow Prestwick International Airport – 48 miles (1 hour #1) www.gpia.co.uk Glasgow Prestwick Airport, Aviation House, Prestwick, KA9 2PL Tel: 0871 223 0700 Ferry Terminals Rosyth Ferry Terminal - 40 miles (55 minutes #1) www.norfolkline.com/EN/Ferry_routes/Rosyth_Zeebrugge/ Norfolkline operate from the Norfolkline terminal to This ferry links Scotland directly to the European Zeebrugge, Dew Way, Rosyth, Fife, Scotland, KY11 2XP mainland. -

Planning Applications Index

North Lanarkshire Council Planning Applications for consideration of Planning and Transportation Committee Committee Date : April 2009 Ordnance Survey maps reproduced from Ordnance Survey with permission of HMSO Crown Copyright reserved APPLICATIONS FOR PLANNING AND TRANSPORTATION COMMITTEE l!jthApril 2009 Page Application No. Applicant Development/Locus Recommendation No 3 C/08/01023/FUL Airdrie North Ltd Construction of Waste to Grant C/o Agent Heat and Energy Plant, Recycling Facility, Access Road and Associated Works 50 S/08/01374/FUL Modern Housing Ltd Erection of Eight Flats and Grant One Residential Building Plot Land At Millbank Road Wishaw 60 S/09/00168/FUL Mr & Mrs Paris Conversion of Integral Refuse Garage to Habitable Room 17 Robert Wynd, Newmains Wishaw Application No: C/08/01023/FUL Date Registered: 22nd August 2008 Applicant: Airdrie North Ltd Clo Agent Agent James Barr Ltd 226 West George Street Glasgow G2 2LN Development: Construction of Waste to Heat and Energy Plant, Recycling Facility, Access Road and Associated Works Location: Land At Former Drumshangie OCCS Greengairs Road Green g a irs North Lanarkshire Ward: 007 Airdrie North Cllrs Cameron, McGuigan, Morgan and S Coyle Grid Reference: 277913668257 File Reference: C/P LIGWG 9OO/C M Site History: Refer to report Development Plan: Glasgow and The Clyde Valley Joint Structure Plan 2000 incorporatingthe Third Alterations 2006. Monklands District Local Plan 1991, Including Finalised First Alterations A, B & C September 1996 Contrary to Development Plan: Yes Consultations: Scottish Environment Protection Agency (Comments) Scottish Natural Heritage (Comments) Transport Scotland (No Objection) National Grid Gas Network (Comments) Scotland Gas Network (Comments) Scottish Power (Comments) Scottish Water (Comments) Historic Scotland (No objection) Architecture and Design Scotland (Comments) West Of Scotland Archaeology Service (Comments) Scottish Wildlife Trust (Comments) Royal Soc.