Maccabean Revolt: Between Tradition and History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE BOOK of DANIEL and the "MACCABEAN THESIS" up Until

Andrews University Seminary Studies, Summer 1983, Vol. 21, No. 2, 129-141. Copyright @ 1983 by Andrews University Press. THE BOOK OF DANIEL AND THE "MACCABEAN THESIS" ARTHUR J. FERCH Avondale College Cooranbong, N. S. W. 2265 Australia Up until about a century ago, the claims laid out in the book of Daniel as to its authorship, origin, etc., during the sixth century B.C. were quite generally accepted. However, since 1890, according to Klaus Koch, this exilic theory has been seriously challenged-so much so, in fact, that today it represents only a minority view among Daniel scho1ars.l The majority hold a view akin to that of Porphyry, the third-century Neoplatonist enemy of Christianity, that the book of Daniel was composed (if not entirely, at least substantially) in the second century B.C. during the religious per- secution of the Jews by the Seleucid monarch Antiochus IV Epiphanes.2 The book is considered to have arisen in conjunction with, or in support of, the Jewish resistance to Antiochus led by Judas Maccabeus and his brothers. Thus, according to this view, designated as the "Maccabean the~is,"~the book of Daniel was composed (at least in part) and/or edited in the second century by an unknown author or authors who posed as a sixth-century statesman-prophet named Daniel and who pretended to offer genuinely inspired predictions (uaticinia ante eventu) which in reality were no more than historical narratives 'This article is based on a section of a paper presented in 1982 to the Daniel and Revelation Committee of the Biblical Research Institute (General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists, Washington, D.C.). -

Honigmanonigman - 9780520275584.Indd9780520275584.Indd 1 228/06/148/06/14 2:382:38 PMPM 2 General Introduction

General Introduction SUMMARY Th e fi rst and second books of Maccabees narrate events that occurred in Judea from the 170s through the 150s and eventually led to the rise of the Hasmonean dynasty: the toppling of the last high priest of the Oniad dynasty, the transforma- tion of Jerusalem into a Greek polis, Antiochos IV’s storming of Jerusalem, his desecration of the temple and his so-called persecution of the Jews, the liberation of the city and rededication of the temple altar by Judas Maccabee, the foundation of the commemorative festival of Hanukkah, and the subsequent wars against Seleukid troops. 1 Maccabees covers the deeds of Mattathias, the ancestor of the Maccabean/Hasmonean family, and his three sons, Judas, Jonathan, and Simon, taking its story down to the establishment of the dynastic transmission of power within the Hasmonean family when John, Simon’s son, succeeded his father; whereas 2 Maccabees, which starts from Heliodoros’s visit to Jerusalem under the high priest Onias III, focuses on Judas and the temple rededication, further dis- playing a pointed interest in the role of martyrs alongside that of Judas. Because of this diff erence in chronological scope and emphasis, it is usually considered that 1 Maccabees is a dynastic chronicle written by a court historian, whereas 2 Macca- bees is the work of a pious author whose attitude toward the Hasmoneans has been diversely appreciated—from mild support, through indiff erence, to hostility. Moreover, the place of redaction of 2 Maccabees, either Jerusalem or Alexandria, is debated. Both because of its comparatively fl amboyant style and the author’s alleged primarily religious concerns, 2 Maccabees is held as an unreliable source of evidence about the causes of the Judean revolt. -

Print Friendly Version

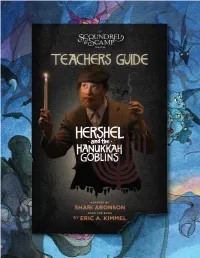

TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 The Holiday of Hanukkah 5 Judaism and the Jewish Diaspora 8 Ashkenazi Jews and Yiddish 9 Latkes! 10 Pickles! 11 Body Mapping 12 Becoming the Light 13 The Nigun 14 Reflections with Playwright Shari Aronson 15 Interview with Author Eric Kimmel 17 Glossary 18 Bibliography Using the Guide Welcome, Teachers! This guide is intended as a supplement to the Scoundrel and Scamp’s production of Hershel & The Hanukkah Goblins. Please note that words bolded in the guide are vocabulary that are listed and defined at the end of the guide. 2 Hershel and the Hanukkah Goblins Teachers Guide | The Scoundrel & Scamp Theatre The Holiday of Hanukkah Introduction to Hanukkah Questions: In Hebrew, the word Hanukkah means inauguration, dedication, 1. What comes to your mind first or consecration. It is a less important Jewish holiday than others, when you think about Hanukkah? but has become popular over the years because of its proximity to Christmas which has influenced some aspects of the holiday. 2. Have you ever participated in a Hanukkah tells the story of a military victory and the miracle that Hanukkah celebration? What do happened more than 2,000 years ago in the province of Judea, you remember the most about it? now known as Palestine. At that time, Jews were forced to give up the study of the Torah, their holy book, under the threat of death 3. It is traditional on Hanukkah to as their synagogues were taken over and destroyed. A group of eat cheese and foods fried in oil. fighters resisted and defeated this army, cleaned and took back Do you eat cheese or fried foods? their synagogue, and re-lit the menorah (a ceremonial lamp) with If so, what are your favorite kinds? oil that should have only lasted for one night but that lasted for eight nights instead. -

Hanukkah Worksheets

Directions: Carefully read the selection. On the first word, circle words that are new to you and underline or highlight phrases that you think are important. HISTORY OF HANUKKAH Adapted from History.com The eight-day Jewish celebration known as Hanukkah or Chanukah commemorates the rededication during the second century B.C. of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, where according to legend Jews had risen up against their Greek-Syrian oppressors in the Maccabean Revolt. Hanukkah, which means “dedication” in Hebrew, begins on the 25th of Kislev on the Hebrew calendar and usually falls in November or December. In 2015 it begins on December 6th. Often called the Festival of Lights, the holiday is celebrated with the lighting of the menorah, traditional foods, games and gifts. The events that inspired the Hanukkah holiday took place during a particularly turbulent phase of Jewish history. Around 200 B.C., Judea—also known as the Land of Israel—came under the control of Antiochus III, the Seleucid king of Syria, who allowed the Jews who lived there to continue practicing their religion. His son, Antiochus IV Epiphanes, proved less benevolent: Ancient sources recount that he outlawed the Jewish religion and ordered the Jews to worship Greek gods. In 168 B.C., his soldiers descended upon Jerusalem, massacring thousands of people and desecrating the city’s holy Second Temple by erecting an altar to Zeus and sacrificing pigs within its sacred walls. Led by the Jewish priest Mattathias and his five sons, a large-scale rebellion broke out against Antiochus and the Seleucid monarchy. -

Chanukah Activity Pack 2020

TTHHEE GGRREEAATT SSYYNNAAGGOOGGUUEE CCHHAANNUUKKAAHH ActivityActivity PackPack 22002200 -- 55778811 T H E S T O R Y O F C H A N U K A H A long, long time ago in the land of Israel, the most special place for the Jewish people was the Temple in Jerusalem. The Temple contained many beautiful objects, including a tall, golden menorah. Unlike menorahs of today, this one had seven (rather than nine) branches. Instead of being lit by candles or light bulbs, this menorah burned oil. Every evening, oil would be poured into the cups that sat on top of the menorah. The Temple would be filled with shimmering light. At the time of the Hanukkah story, a mean king named Antiochus ruled over the land of Israel. “I don’t like these Jewish people,” declared Antiochus. “They are so different from me. I don’t celebrate Shabbat or read from the Torah, so why should they?” Antiochus made many new, cruel rules. “No more celebrating Shabbat! No more going to the Temple, and no more Torah!” shouted Antiochus. He told his guards to go into the Temple and make a mess. They brought mud, stones, and garbage into the Temple. They broke furniture and knocked things down; they smashed the jars of oil that were used to light the menorah. Antiochus and his soldiers made the Jews feel sad and angry. A Jewish man named Judah Maccabee said, “We must stop Antiochus! We must think of ways to make him leave the land of Israel.” At first, Judah’s followers, called the Maccabees, were afraid. -

1 Maccabees, Chapter 1

USCCB > Bible 1 MACCABEES, CHAPTER 1 From Alexander to Antiochus. 1 a After Alexander the Macedonian, Philip’s son, who came from the land of Kittim,* had defeated Darius, king of the Persians and Medes, he became king in his place, having first ruled in Greece. 2 He fought many battles, captured fortresses, and put the kings of the earth to death. 3 He advanced to the ends of the earth, gathering plunder from many nations; the earth fell silent before him, and his heart became proud and arrogant. 4 He collected a very strong army and won dominion over provinces, nations, and rulers, and they paid him tribute. 5 But after all this he took to his bed, realizing that he was going to die. 6 So he summoned his noblest officers, who had been brought up with him from his youth, and divided his kingdom among them while he was still alive. 7 Alexander had reigned twelve years* when he died. 8 So his officers took over his kingdom, each in his own territory, 9 and after his death they all put on diadems,* and so did their sons after them for many years, multiplying evils on the earth. 10 There sprang from these a sinful offshoot, Antiochus Epiphanes, son of King Antiochus, once a hostage at Rome. He became king in the one hundred and thirty-seventh year* of the kingdom of the Greeks. Lawless Jews. 11 b In those days there appeared in Israel transgressors of the law who seduced many, saying: “Let us go and make a covenant with the Gentiles all around us; since we separated from them, many evils have come upon us.” 12 The proposal was agreeable; 13 some from among the people promptly went to the king, and he authorized them to introduce the ordinances of the Gentiles. -

Plotting Antiochus's Persecution

JBL123/2 (2004) 219-234 PLOTTING ANTIOCHUS'S PERSECUTION STEVEN WEITZMAN [email protected] Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405-7005 The history of religious persecution could be said to have begun in 167 B.C.E. when the Seleucid king Antiochus IV issued a series of decrees outlawing Jewish religious practice. According to 1 Maccabees, anyone found with a copy of the Torah or adhering to its laws—observing the Sabbath, for instance, or practicing circumcision—was put to death. Jews were compelled to build altars and shrines to idols and to sacrifice pigs and other unclean animals. The temple itself was desecrated by a "desolating abomination" built atop the altar of burnt offering. The alternative account in 2 Maccabees adds to the list of outrages: the temple was renamed for Olympian Zeus, and the Jews were made to walk in a procession honoring the god Dionysus. Without apparent precedent, the king decided to abolish an entire religion, suppressing its rites, flaunting its taboos, forcing the Jews to follow "customs strange to the land." Antiochus IV s persecution of Jewish religious tradition is a notorious puz zle, which the great scholar of the period Elias Bickerman once described as "the basic and sole enigma in the history of Seleucid Jerusalem."1 Earlier for eign rulers of the Jews in Jerusalem, including Antiochus s own Seleucid fore bears, were not merely tolerant of the religious traditions of their subjects; they often invested their own resources to promote those traditions.2 According to Josephus, Antiochus III, whose defeat of the Ptolemaic kingdom at the battle of Panium in 200 B.C.E. -

The Maccabees and Their Place in Jewish History. Sixth Grade Activity

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 469 517 SO 034 254 AUTHOR Mollet, Joyce; Mollet, David TITLE The Maccabees and Their Place in Jewish History. Sixth Grade Activity. Schools of California Online Resources for Education (SCORE): Connecting California's Classrooms to the World. INSTITUTION San Bernardino County Superintendent of Schools, CA. PUB DATE 2000 -00 -00 NOTE 25p. AVAILABLE FROM Schools of California Online Resources for Education, San Bernardino County Superintendent of Schools, 601 North East Street, San Bernardino, CA 92410-3093. E-mail: webmaster @score.rims.kl2.ca.us; Web site: http://score.rims.k12.ca.us. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Learner (051) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Culture; Evaluation Criteria; Grade 6; Intermediate Grades; *Jews; *Judaism; Language Arts; Sciences; *Social Studies; Special Needs Students; State Standards; Student Research; *Writing Assignments IDENTIFIERS California; *Jewish History ABSTRACT On November 17, 1995 the following news item appeared in "Time Magazine": "Long-lost cave reveals burial tombs of Maccabees." You (the student) are a journalist who has been asked by your editor to follow up that news item with an in-depth feature a two page spread with text and graphics entitled "The Life and Times of Judah Maccabee." For the student, this lesson plan delineates the task; provides a five step preparation process for the task (writing four articles, one by each member of the group); gives learning advice; suggests a concluding activity; poses several reflection questions; and offers an extension activity. Extensive historical background information is included. Guided reading activities and resource list are included. -

The Hanuka Festival- a Guipe, Forthe Restof Us

, NEWLYREVISED edition, -' i -'riffi:';,'i;,;',;,' tikf)ian'biiii,:f;'"' THE HANUKA FESTIVAL- A GUIPE, FORTHE RESTOF US by Hershl Hartman, vegyayzer A few words before we begin... Jews, both adults and children, even those from culturally consciousor religiously observant homes, cannot be convinced that khanikeis a reasonable substitute for the tinsel, glitter and sentimentality that surround Xmas, the American version of Christmasthat has virtually engulfed the world. Accordingly, it is nof the purpose of this work to help project khanikeas an "alternative Xmas" but, rather, to provide non-observantJewish families with a factual understanding of the festival'sorigins and traditions so that it may be celebratedmeaningfully and joyously in its own right. Why "...for the rest of us"? Increasingly,American Jews are identifying with their ethnic culture,rather than with the Jewishreligion. At the sametime, Hanuka is being projected more aggressivelyas a religiousholiday, focused on the "Miracle of the Lights," purporting to celebrate"history's first victorious struggle for religious freedom," to quote the inevitable editorial in your local newspaper.Actually, as we shall see, Hanuka is nothing of the sort. l'he issuesof "religious freedom" vs. "national liberation"vs. "multicultural rights" wereactually confronted back in the secondcentury B.C.E.,albeit with other terminology.'l'hisbooklet seeksto separate fact from fanry so that those who identify with Jewishculture will not feel excluded from celebratingthe festival. Now, about the matter of spelling. 1'he "right" way to spell it is: il!'tJrt.What is 'l'he the "best" way to transliteratethe Hebrew into English? earliest"official" form was Chanukah or its inexplicablevariants: Channukah and Chanukkah. -

Possible Misreading in 1 Maccabees 7:34 in Light of Its Biblical Model

JBL 138, no. 4 (2019): 777–789 https://doi.org/10.15699/jbl.1384.2019.5 Possible Misreading in 1 Maccabees 7:34 in Light of Its Biblical Model matan orian [email protected] Center for the Study of Conversion and Inter-Religious Encounters, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer Sheva, 8410501, Israel First Maccabees 7:34 employs four verbs to describe the offensive speech by Nicanor, the Seleucid general, addressed to the Jewish elders and priests. The third verb indicates that Nicanor defiled his audience. While this has led scholars to associate 1 Maccabees with the Jewish concept of gentile impurity, several factors suggest that, at this point, an error found its way into the Greek translation from the original Hebrew. The present argument comprises three steps. First, I use the biblical Sennacherib story, featured in the background of the Nicanor episode in 1 Maccabees, as a means of reconstructing the relevant original Hebrew verb employed by 1 Maccabees. Second, I suggest a possible misreading of one letter on the part of the Greek translator. Finally, I propose that a similar, earlier verse in 1 Maccabees, 1:24b, may have been conducive to the translator’s commission of this mistake, thus offering an insight into his way of thinking. I. A Verb Clearly out of Context First Maccabees 7:34 employs four verbs to describe the insulting nature of the speech by Nicanor, the Seleucid general, directed at the Jewish elders and the priests of the Jerusalem temple who emerged from the temple to greet him: “he mocked them, derided them, defiled them, and spoke arrogantly” (ἐμυκτήρισεν αὐτοὺς καὶ κατεγέλασεν αὐτῶν καὶ ἐμίανεν αὐτοὺς καὶ ἐλάλησεν ὑπερηφάνως).1 The third verb, “defile,” plainly differs from the other verbs in this verse: it does not relate to the nature of the speech but rather to a cultic or ritual consequence of some physical act committed by Nicanor. -

The Septuagint As a Holy Text – the First 'Bible' of the Early Church

HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-8050, (Print) 0259-9422 Page 1 of 9 Original Research The Septuagint as a holy text – The first ‘bible’ of the early church Author: This article acknowledges the fact that historically there are two phases in the emergence of the 1 Johann Cook Septuagint – a Jewish phase and a Christian one. The article deals first with methodological Affiliation: issues. It then offers a historical orientation. In the past some scholars have failed to distinguish 1Department of Ancient between key historical phases: the pre-exilic/exilic (Israelite – 10 tribes), the exilic (the Studies, Faculty of Arts and Babylonian exile ‒ 2 tribes) and the post-exilic (Judaean/Jewish). Many scholars are unaware Social Sciences, University of of the full significance of the Hellenistic era, including the Seleucid and Ptolemaic eras and Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch, South Africa their impact on ‘biblical’ textual material. Others again overestimate the significance of this era; the Greek scholar Evangelia Dafni is an example. Many are uninformed about the Persian Corresponding author: era, which includes the Achaemenid, Parthian and Sassanian eras, each one of which had an Johann Cook, impact on Judaism. An example is the impact of Persian dualism. Another problem is the [email protected] application of the concept of ‘the Bible’. The notion of ‘Bible’ applies only after the 16th century Dates: Common Era, specifically after the advent of the printing press. Earlier, depending on the Received: 18 May 2020 context, we had clay tablets (Mesopotamia), vella (Levant-Judah) and papyri (Egypt) to write Accepted: 06 July 2020 on. -

Katell Berthelot Introduction

ELECTRUM * Vol. 21 (2014): 73–85 doi: 10.4467/20800909EL.14.001.2780 www.ejournals.eu/electrum JUDAS MACCABEUS’ WARS AGAINST JUDAEA’S NEIGHBOURS IN 1 MACCABEES 5: A REASSESSMENT OF THE EVIDENCE Katell Berthelot CNRS / Aix-Marseille University Abstract: The fi fth chapter of the First Book of Maccabees recounts a whole range of wars waged by Judas Maccabeus against Judaea’s neighbours, who are depicted as threatening the lives of the Jews living in their midst. The account of these punitive expeditions contains the only explicit reference found in the book to an anathema (ḥerem) against a foreign people, a reference which has led some scholars to see Judas as re-enacting the biblical prescription of the ḥerem against the Canaanites. In contrast with this interpretation, the present article argues that the description in 1 Maccabees 5 is highly literary and rhetorical, and that it is part of a strategy which aims at pre- senting Judas as the heir of the fi rst kings of Israel. In particular, a careful literary analysis shows that nearly all the differences between the accounts in 1 and 2 Maccabees can be explained by tak- ing into consideration the project of the author to present Judas’s military expeditions in the light of Saul’s campaigns, following 1 Samuel 10–15 (especially 14:47–48). Given the indebtedness of 1 Maccabees 5 toward such biblical traditions, the historicity of Judas’s wars against Judaea’s neighbours should be re-assessed. Key words: history of Second Temple Judaism, Hasmoneans, 1 Maccabees 5, Judas Maccabeus, wars, biblical models, Saul.