Historical Cadastral Maps of Cluj-Napoca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REGIONAL and LOCAL DEVELOPMENT in TIMES of POLARISATION Re-Thinking Spatial Policies in Europe New Geographies of Europe

NEW GEOGRAPHIES OF EUROPE Edited by THILO LANG AND FRANZISKA GÖRMAR REGIONAL AND LOCAL DEVELOPMENT IN TIMES OF POLARISATION Re-Thinking Spatial Policies in Europe New Geographies of Europe Series Editors Sebastian Henn Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena Jena, Germany Ray Hudson Durham University Durham, UK Thilo Lang Leibniz Institute for Regional Geography University of Leipzig Leipzig, Germany Judit Timár Hungarian Academy of Sciences Budapest, Hungary Tis series explores the production and reshaping of space from a comparative and interdisciplinary perspective. By drawing on con- temporary research from across the social sciences, it ofers novel insights into ongoing spatial developments within and between the various regions of Europe. It also seeks to introduce new geographies at the edges of the European Union and the interplay with bordering areas at the Mediterranean, African and eastern Asian interfaces of the EU. As a result, this series acts as an important forum for themes of pan-European interest and beyond. Te New Geographies of Europe series welcomes proposals for monographs and edited volumes taking a comparative and interdisciplinary approach to spatial phenomena in Europe. Contributions are especially welcome where the focus is upon novel spatial phenomena, path-dependent processes of socio-economic change or policy responses at various levels throughout Europe. Suggestions for topics also include the relationship between the state and citizens, the idea of fragile democracies, the economics of regional separation, -

Investeşte În Oameni!

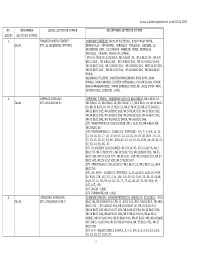

Investeşte în oameni! PROGRAMUL DE FORMARE CONTINUĂ PROIECTUL „COMPETENŢE CHEIE TIC ÎN CURRICULUMUL ŞCOLAR” Repartitia pe grupe la informatică Centrul de formare - Colegiul Economic ”M. Kogălniceanu” Focșani Formator - Ciubotaru Bogdan Nr. Numele şi prenumele Scoala Crt. 1. Tenea Ovidiu Ernest Scoala cu cls I-VIII nr. 2 Marasesti 2. Măciucă Marius Liceul Pedagogic “Spiru Haret” Focşani 3. Ionescu Cristina Şcoala cu cls I-VIII „Anghel Saligny” 4. Țîțu Ion Colegiul National „Alexandru Ioan Cuza” 5. Stanila Daniela Grupul Scolar ”Grigore Gheba” Dumitrești 6. Grigore Andreea-Alina Şcoala cu cls. I-VIII Homocea 7. Pavăl Laura Școala ”Ion Basgan” 8. Dima Lenuţa Școala ”Ion Basgan” 9. Dumitru Violeta Școala ”Mareșal Averescu” Adjud 10. Stroie Marcel Școala ”D. Zamfirescu” Focșani 11. Grecu Daniel Valentin Scoala cu clasele I-VIII Slobozia Bradului 12. Colin Liliana Colegiul Naţional „Unirea” 13. Vulpoiu Genovica Colegiul Naţional „Unirea” 14. Neşu Liliana Colegiul Naţional „Unirea” 15. Onea Emil Colegiul Naţional „Unirea” 1/14 Investeşte în oameni! PROGRAMUL DE FORMARE CONTINUĂ PROIECTUL „COMPETENŢE CHEIE TIC ÎN CURRICULUMUL ŞCOLAR” Repartitia pe grupe limba și literatura română Centrul de formare - CCD ”S. Mehedinți” Vrancea Formator – Silvia Chelariu Grupa 1 Nr. Numele şi prenumele Scoala Crt. 1. Opait Anca Scoala cu cls I-VIII nr. 2 Marasesti 2. Catrinoiu Maricica Scoala cu cls I-VIII Dimitrie Gusti Nereju 3. Nistoroiu Luminita Scoala cu cls I-VIII Dimitrie Gusti Nereju 4. Stanciu Ionela Scoala cu cls I-VIII ,,Mihail Armencea’’ Adjud 5. Severin Florentina Scoala cu cls I-VIII ,,Mihail Armencea’’ Adjud 6. Novac Maricica Scoala cu cls I-VIII Paunesti 7. Marcu Nicoleta Scoala cu cls I-VIII Paunesti 8. -

JUDEȚ UAT NUMAR SECȚIE INSTITUȚIE Adresa Secției De

NUMAR JUDEȚ UAT INSTITUȚIE Adresa secției de votare SECȚIE JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 1 Directia Silvică Vrancea Directia Silvică Vrancea Strada Aurora ; Nr. 5 JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 2 Teatrul Municipal Focşani Teatrul Municipal Focşani Strada Republicii ; Nr. 71 Biblioteca Judeţeană "Duiliu Zamfirescu" Strada Mihail JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 3 Biblioteca Judeţeană Duiliu Zamfirescu"" Kogălniceanu ; Nr. 12 Biblioteca Judeţeană "Duiliu Zamfirescu" Strada Nicolae JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 4 Biblioteca Judeţeană Duiliu Zamfirescu"" Titulescu ; Nr. 12 Şcoala "Ştefan cel Mare" - intrarea principală Strada JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 5 Şcoala Ştefan cel Mare" - intrarea principală" Ştefan cel Mare ; Nr. 12 Şcoala "Ştefan cel Mare" - intrarea elevilor Strada Ştefan JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 6 Şcoala Ştefan cel Mare" - intrarea elevilor" cel Mare ; Nr. 12 Şcoala "Ştefan cel Mare" - intrarea secundara Strada JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 7 Şcoala Ştefan cel Mare" - intrarea secundara" Ştefan cel Mare ; Nr. 12 JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 8 Colegiul Tehnic Traian Vuia"" Colegiul "Tehnic Traian Vuia" Strada Coteşti ; Nr. 52 JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 9 Colegiul Tehnic Traian Vuia"" Colegiul "Tehnic Traian Vuia" Strada Coteşti ; Nr. 52 Poliţia Municipiului Focşani Strada Prof. Gheorghe JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 10 Poliţia Municipiului Focşani Longinescu ; Nr. 33 Poliţia Municipiului Focşani Strada Prof. Gheorghe JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 11 Poliţia Municipiului Focşani Longinescu ; Nr. 33 Colegiul Economic "Mihail Kogălniceanu" Bulevardul JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 12 Colegiul Economic Mihail Kogălniceanu"" Gării( Bulevardul Marx Karl) ; Nr. 25 Colegiul Economic "Mihail Kogălniceanu" Bulevardul JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 13 Colegiul Economic Mihail Kogălniceanu"" Gării( Bulevardul Marx Karl) ; Nr. 25 JUDEŢUL VRANCEA MUNICIPIUL FOCŞANI 14 Şcoala Gimnazială nr. -

Beetles from Sălaj County, Romania (Coleoptera, Excluding Carabidae)

Studia Universitatis “Vasile Goldiş”, Seria Ştiinţele Vieţii Vol. 26 supplement 1, 2016, pp.5- 58 © 2016 Vasile Goldis University Press (www.studiauniversitatis.ro) BEETLES FROM SĂLAJ COUNTY, ROMANIA (COLEOPTERA, EXCLUDING CARABIDAE) Ottó Merkl, Tamás Németh, Attila Podlussány Department of Zoology, Hungarian Natural History Museum ABSTRACT: During a faunistical exploration of Sǎlaj county carried out in 2014 and 2015, 840 beetle species were recorded, including two species of Community interest (Natura 2000 species): Cucujus cinnaberinus (Scopoli, 1763) and Lucanus cervus Linnaeus, 1758. Notes on the distribution of Augyles marmota (Kiesenwetter, 1850) (Heteroceridae), Trichodes punctatus Fischer von Waldheim, 1829 (Cleridae), Laena reitteri Weise, 1877 (Tenebrionidae), Brachysomus ornatus Stierlin, 1892, Lixus cylindrus (Fabricius, 1781) (Curculionidae), Mylacomorphus globus (Seidlitz, 1868) (Curculionidae) are given. Key words: Coleoptera, beetles, Sǎlaj, Romania, Transsylvania, faunistics INTRODUCTION: László Dányi, LF = László Forró, LR = László The beetle fauna of Sǎlaj county is relatively little Ronkay, MT = Mária Tóth, OM = Ottó Merkl, PS = known compared to that of Romania, and even to other Péter Sulyán, VS = Viktória Szőke, ZB = Zsolt Bálint, parts of Transsylvania. Zilahi Kiss (1905) listed ZE = Zoltán Erőss, ZS = Zoltán Soltész, ZV = Zoltán altogether 2,214 data of 1,373 species of 537 genera Vas). The serial numbers in parentheses refer to the list from Sǎlaj county mainly based on his own collections of collecting sites published in this volume by A. and partially on those of Kuthy (1897). Some of his Gubányi. collection sites (e.g. Tasnád or Hadad) no longer The collected specimens were identified by belong to Sǎlaj county. numerous coleopterists. Their names are given under Vasile Goldiş Western University (Arad) and the the names of beetle families. -

Planul Integrat De Management Al Ariei Naturale Protejate Pădurea

Anexã Planul de management al ariei naturale protejate ROSPA0141 Subcarpaţii Vrancei 1 CUPRINS ACRONIME ȘI ABREVIERI .............................................................................................................. 5 CAPITOLUL I. INTRODUCERE.................................................................................................................... 6 - 1.1. Scurtă descriere a planului de management ........................................................... 6 - 1.2. Scurtă descriere a ariei naturale protejate ............................................................. 6 - 1.3. Cadrul legal referitor la aria naturală protejată și la elaborarea planului de management ................................................................................................................... 9 - 1.4. Procesul elaborării planului. ................................................................................ 10 - 1.5. Procedura de implementare a planului de management ...................................... 11 CAPITOLUL II.: DESCRIEREA ARIEI NATURALE PROTEJATE .................................................................... 11 - 2.1. Informații generale ................................................................................................ 11 2.1.1. Localizarea ariei naturale protejate .................................................................... 11 2.1.2. Folosința şi forma de proprietate a terenurilor ................................................. 12 2.1.3. Limitele ariei naturale protejate ......................................................................... -

A Malaco-Faunistical Study of Salaj County/Szilágyság, Romania with Taxonomical Notes

Studia Universitatis “Vasile Goldiş”, Seria Ştiinţele Vieţii Vol. 25 issue 3, 2015, pp.179-191 © 2015 Vasile Goldis University Press (www.studiauniversitatis.ro) A MALACO-FAUNISTICAL STUDY OF SALAJ COUNTY/SZILÁGYSÁG, ROMANIA WITH TAXONOMICAL NOTES Zoltán Péter Erőss1, 1Department of Zoology, Hungarian Natural History Museum, ABSTRACT. In the framework of the research program of the Hungarian Natural History Museum ”Invertebrate faunistical investigation of Sălaj county”, numerous molluscs (87 species) were collected in 2014-2015. Compared to other parts of the Carpathians, the mollusc fauna of Sălaj county is relatively poor - after this investigations this number is increased to 114 species - considering either the total species richness or the number of taxa. In the list I enumerate the results of recent collections, adding and also comparing with the results by Domokos and Lennert, 2009 in connection the area of judetul Sălaj /Szilágyság. From faunistical and conservation point the most important results are species of Acicula perpusilla, Agardhiella lamellosa, Drobacia banatica, Unio crassus, Vertigo angustior, Vertigo moulinsiana and Vertigo substriata. thing worth mentioning. The most important outcome of this study was the discovery of a new Bythinella species: Bythinella gregoi GLÖER & ERŐSS and Alzoniella (?) species which is a new species and genus for Romania. The other important finding a very big empty shell of Mastus bielzi which could be a new subspecies. These recent researches made a result rare or new endemic species, it pays attention that the well-known, but not so deeply researched areas can be faunistical or scientific surprised. Keywords: Mollusca, Romania, Sălaj, Faunistics, Bythinella, Alzoniella, Mastus, Carpathian INTRODUCTION: framework of this program, there was a good Sălaj county is situated in the north-west of the opportunity to summarize these few literature data. -

POPULATIA DUPA DOMICILIU La 1 Ianuarie Pe Sexe Si Localitati

POPULATIA DUPA DOMICILIU la 1 ianuarie pe sexe si localitati Ani Anul Anul Anul 2008 Anul 2009 Anul 2010 Anul 2011 Anul 2012 Anul 2013 Anul 2014 Anul 2015 Anul 2016 2017 2018 Sexe Judete Localitati UM: Numar persoane Numar Numar Numar Numar Numar Numar Numar Numar Numar Numar Numar persoane persoane persoane persoane persoane persoane persoane persoane persoane persoane persoane Total Vrancea TOTAL 399405 399345 398690 398076 396894 395687 394345 393204 391780 390148 387994 174744 MUNICIPIUL - - 98054 97502 97156 96852 96498 95858 95470 95171 94520 93780 93005 FOCSANI 174860 MUNICIPIUL - - 20839 20781 20776 20882 20845 20750 20661 20558 20555 20448 20357 ADJUD 174922 ORAS - - 13440 13549 13550 13537 13545 13555 13517 13479 13460 13451 13452 MARASESTI 175019 ORAS - - 8744 8904 9106 9337 9448 9557 9591 9639 9658 9689 9661 ODOBESTI 175055 ORAS - - 9650 9565 9560 9517 9507 9460 9429 9394 9301 9301 9261 PANCIU 175126 ANDREIASU - - 2138 2127 2099 2041 2011 1987 1950 1936 1912 1856 1816 DE JOS - - 175206 BALESTI 2212 2197 2175 2163 2132 2101 2067 2041 2005 1984 1955 - - 175224 BARSESTI 1641 1621 1601 1547 1538 1519 1498 1467 1439 1426 1410 - - 178929 BILIESTI 2412 2446 2473 2504 2511 2520 2497 2511 2500 2475 2481 - - 175260 BOGHESTI 1754 1739 1718 1723 1690 1684 1638 1623 1598 1597 1557 - - 175368 BOLOTESTI 4817 4852 4895 4851 4821 4825 4840 4832 4839 4843 4772 - - 175439 BORDESTI 1866 1879 1867 1843 1830 1826 1820 1792 1774 1782 1750 - - 175466 BROSTENI 2299 2314 2303 2300 2291 2281 2278 2266 2270 2282 2288 - - 175509 CHIOJDENI 2515 2538 2535 -

Monografia Comunei Tîmboieşti

IULIAN ROTARU MONOGRAFIA COMUNEI TÎMBOIEŞTI BUCUREŞTI 2009 IULIAN ROTARU MONOGRAFIA COMUNEI TÎMBOIEŞTI BUCUREŞTI 2009 0 Cuvânt înainte În ziua de 17 ianuarie 2009, o zi frumoasă pentru jumătatea iernii calendaristice - ziua Cuv. Antonie cel Mare - am gândit pentru prima oară la o lucrare (poate prea pretenţios spus carte) despre înaintaşi, locurile naşterii şi ale copilăriei, despre obiceiurile, ocupaţiile, bucuriile şi necazurile celor dintre care am pornit în viaţă. Timpul curge nemilos, suntem cu toţii trecători şi este de dorit ca în urma fiecăruia să rămână ceva durabil, iar cei ce vin după noi să-şi cunoască rădăcinile. Multe lucruri sunt puse pentru prima oară pe hârtie şi sper din tot sufletul ca toate cele povestite să se constituie într-un prilej de aducere aminte despre moşii şi strămoşii noştri, unii ştiuţi doar din poze, care ne veghează din cele două cimitire ale comunei sau de pe meleaguri îndepărtate, unde au murit pentru cauze străine firii şi intereselor ţăranului român, „carne de tun” pentru cârmuitorii trecători ai Ţării Româneşti. Cartea este expresia recunoştinţei pentru părinţii şi pentru dascălii mei şi un modest omagiu pentru locuitorii comunei Tîmboieşti. Iulian Rotaru 1 2 INTRODUCERE România postdecembristă a generat creşterea interesului pentru studiul genezei şi evoluţiei diverselor localităţi şi prezentarea unor elemente noi din viaţa acestora. Lucrarea de faţă se constituie într-o astfel de încercare, având ca obiect istoria multiseculară a comunei Tîmboieşti şi a locuitorilor săi. Nu există nici un document pe această temă, iar documentarea a fost una anevoioasă şi de durată, până în 1989 existând în general o preocupare modestă pentru realizarea unor astfel de lucrări. -

Strategia De Dezvoltare Durabilă a Comunei Românași, Judeţul Sălaj

STRATEGIA DE DEZVOLTARE DURABILĂ A COMUNEI ROMÂNAȘI, JUDEŢUL SĂLAJ 1 CUPRINS ARGUMENT ......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 CAPITOLUL 1. METODOLOGIA DE ELABORARE A STRATEGIEI PRIVIND DEZVOLTAREA DURABILĂ .................. 5 1.1. Considerații generale ............................................................................................................................................. 5 1.2. Principiile dezvoltării strategice durabile............................................................................................................. 5 1.3. Planificarea strategică ........................................................................................................................................... 5 1.4. Elaborarea strategiei de dezvoltare durabilă a comunei Românași ................................................................... 7 CAPITOLUL 2. PLANIFICAREA STRATEGICĂ LA NIVEL EUROPEAN, NAȚIONAL, REGIONAL .................................. 8 2.1. Cadrul strategic european de dezvoltare durabilă .............................................................................................. 8 2.2. Cadrul strategic comun (CSC) 2014 - 2020 ........................................................................................................ 10 2.3. Cadrul strategic național .................................................................................................................................... -

Anexa La Ordinul Prefectului Nr.83/25.04.2007

Anexa la Ordinul prefectului nr.83/25.04.2007 NR. DENUMIREA SEDIUL SECŢIEI DE VOTARE DELIMITAREA SECŢIEI DE VOTARE SECŢIEI SECŢIEI DE VOTARE 1. FUNDAŢIA PENTRU TINERET CUPRINDE STRĂZILE: NICOLAE BĂLCESCU, BUDAY NAGY ANTAL, ZALĂU STR: 22 DECEMBRIE 1989 NR.1 BRĂDETULUI, CĂPRIOAREI, CERBULUI, CIREŞULUI, DECEBAL, 22 DECEMBRIE 1989, C.D.GHEREA, MERILOR, MORII, OBORULUI, PARCULUI, PĂDURII, PRUNILOR, STÂNEI, STR GH. DOJA CU BLOCURILE: NR.4 BLOC D4, NR.6 BLOC D6 , NR.6/A BLOC D6/A , NR.8 BLOC.D8 , NR.10 BLOC D10, NR 10/A BLOC D10/A, NR.12 BLOC D12, NR.14 BLOC D14, NR.18 BLOC D18, NR20 BLOC D20 , NR.22 BLOC D22 , NR.24 BLOC D24, NR.26 BLOC D26, NR.26/A BLOC D26/A. ALEXANDRU FILIPIDE , DUMITRU MĂRGINEANU, EMIL BOTA ,IOAN MANGO, IOAN CARAION, LEONTIN GHERGARIU , LUCIAN BLAGA, MIRON RADU PARASCHIVESCU, MARIN SORESCU, NICOLAE LABIŞ ,PETRI MOR , SIMION OROS, SZIKSZAI LAJOS. 2. CĂMIN DE COPII NR.1 CUPRINDE STRADA: GHEORGHE DOJA CU BLOCURILR: NR.1 BLOC 14, ZALĂU STR. GH.DOJA NR.19 NR.3 BLOC 15, NR.5 BLOC 16, NR.7 BLOC 17, NR.9 BLOC 18, NR.11 BLOC 19, NR.13 BLOC 20, NR.15 BLOC 21, NR.17 BLOC 22, NR.23 BLOC D23, NR.25 BLOC D25, NR.28 BLOC D28, NR.30 BLOC D30, NR.32 BLOC D32, NR.34 BLOC D34, NR.36 BLOC D36, NR.38 BLOC D38, NR.40 BLOC D40, NR.42 BLOC D42, NR. 42/A BLOC D42/A, NR.48 BLOC D48. STR. MIHAI EMINESCU CU BLOCURILE :NR.2 BLOC E2, NR.4 BLOC E4, NR.6 BLOC E6. -

Hungarian Name Per 1877 Or Onliine 1882 Gazetteer District

Hungarian District (jaras) County Current County Current Name per German Yiddish pre-Trianon (megye) pre- or equivalent District/Okres Current Other Names (if 1877 or onliine Current Name Name (if Name (if Synogogue (can use 1882 Trianon (can (e.g. Kraj (Serbian okrug) Country available) 1882 available) available) Gazetteer) use 1882 Administrative Gazetteer Gazetteer) District Slovakia) Borsod-Abaúj- Abaujvár Füzéri Abauj-Torna Abaújvár Hungary Rozgony Zemplén Borsod-Abaúj- Beret Abauj-Torna Beret Szikszó Zemplén Hungary Szikszó Vyšný Lánc, Felsõ-Láncz Cserehát Abauj-Torna Vyšný Lánec Slovakia Nagy-Ida Košický Košice okolie Vysny Lanec Borsod-Abaúj- Gönc Gönc Abauj-Torna Gönc Zemplén Hungary Gönc Free Royal Kashau Kassa Town Abauj-Torna Košice Košický Košice Slovakia Kaschau Kassa Borsod-Abaúj- Léh Szikszó Abauj-Torna Léh Zemplén Hungary Szikszó Metzenseife Meczenzéf Cserehát Abauj-Torna Medzev Košický Košice okolieSlovakia n not listed Miszloka Kassa Abauj-Torna Myslava Košický Košice Slovakia Rozgony Nagy-Ida Kassa Abauj-Torna Veľká Ida Košický Košice okolie Slovakia Großeidau Grosseidau Nagy-Ida Szádelõ Torna Abauj-Torna Zádiel Košický Košice Slovakia Szántó Gönc Abauj-Torna Abaújszántó Borsod-Abaúj- Hungary Santov Zamthon, Szent- Szántó Zemplén tó, Zamptó, Zamthow, Zamtox, Abaúj- Szántó Moldava Nad Moldau an Mildova- Slovakia Szepsi Cserehát Abauj-Torna Bodvou Košický Košice okolie der Bodwa Sepshi Szepsi Borsod-Abaúj- Szikszó Szikszó Abauj-Torna Szikszó Hungary Sikso Zemplén Szikszó Szina Kassa Abauj-Torna Seňa Košický Košice okolie Slovakia Schena Shenye Abaújszina Szina Borsod-Abauj- Szinpetri Torna Abauj-Torna Szinpetri Zemplen Hungary Torna Borsod-Abaúj- Hungary Zsujta Füzér Abauj-Torna Zsujta Zemplén Gönc Borsod-Abaúj- Szántó Encs Szikszó Abauj-Torna Encs Hungary Entsh Zemplén Gyulafehérvár, Gyula- Apoulon, Gyula- Fehérvár Local Govt. -

' Din 9-Q -V 20

GUVERNULROM;,NIEI INSTITUTIAPREFECTULUI JUDETULVRANCEA /#4 ' 0RDtN\R. -v din 9-q 20 11, privind actualizareacomponentrei Centnrtui l,ocal de CombatereI Bolilor Prefectuljudefului Vrancea, - vazandrefefatul ft. 7133122.05,2012lntocm it de ServiciulAfaceri Europcne, CooperareInternatrional{, Ser.vicii publice Deconcentratepri0 care se propunc conponenleiCentrului Local de Combatere a Bolilor; ln .^- temeiulprevederilor Legii nr. l/2008pentru actualizarea $i completafeaOC t1t.42/2004 privind organizareaacrjvitafii sa;itar vetefinare $i pentrusigutanla alimentelor; - ^ in bazaaft, 26,alin. I 9i 2 djn LegeaN.34012004 privind prcleclul qi instrrulra prelbctului,republicalil, emit u ndtorul ORDIN Art. I - Seactuali conponenlaCentrului Local de Combatcrca Bolilor. constituitprin OrdinulPrefectu ui 263124.102011,conforn Anexelor I - 4la prezentul Ordin. Ar.t,3-incepandcu emiteriiprezentului ordin orice alte dispozi{ii contmfe iii irceteazSaplicabilitatea. Art. 4 " Prcvederile tului ordin vor fi comunicateDirecliei Sanitar Veterinareqi pentruSiguranfa limentelor,Direcfiei pentru AgriculturA, Oflciului pentrLr Arneliorareqi Reproductieln je,Inspectoratului Judefean de Polilie,Directiei de SanetatePublica, Agenliei pe ProteciiaMediului, autoritdlilor publice locale, precum gi membrilorComitetuluj Jud pentruSitualii de Urgenlaprevizuti ?n Anexa 1, de cAtl'eCompartimentul aposti autorizdriti atribuirede denumiri,ofdine prel,ect - ServiciulJuridic din cadrul Insti iei Prefectuluijudetul Vrancea. PREFECT, Contrasemneazi, utivDSVSA Vrancea, rianaAmericii