Issue 9 Final Svh 05 21 12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kankadhara Stotram in English Version – with Meaning

Kanakadhara Stotram – http://Divine-Thought.blogspot.com/ Kankadhara Stotram in English Version – with Meaning Mahalakshmi blessings - Kanakadhara Stotram . (Draft Composed by [email protected] ) 1 Angam hare pulaka bhooshanamasrayanthi, Bhringanga neva mukulabharanam thamalam, Angikrithakhila vibhuthirapanga leela, Mangalyadasthu mama mangala devathaya. To the Hari who wears supreme happiness as Ornament, The Goddess Lakshmi is attracted, Like the black bees getting attracted, To the unopened buds of black Tamala[1] tree, Let her who is the Goddess of all good things, Grant me a glance that will bring prosperity. 2 Mugdha muhurvidhadhadathi vadhane Murare, Premathrapapranihithani gathagathani, Mala dhrishotmadhukareeva maheth pale ya, Sa ne sriyam dhisathu sagarasambhavaya. Again and again return ,those glances, Filled with hesitation and love, Of her who is born to the ocean of milk, To the face of Murari[2], Like the honey bees to the pretty blue lotus, And let those glances shower me with wealth. 3 Ameelithaksha madhigamya mudha Mukundam Anandakandamanimeshamananga thanthram, Akekara stiththa kaninika pashma nethram, Bhoothyai bhavenmama bhjangasayananganaya. With half closed eyes stares she on Mukunda[3], Filled with happiness , shyness and the science of love, On the ecstasy filled face with closed eyes of her Lord, And let her , who is the wife of Him who sleeps on the snake, Shower me with wealth. 4 Bahwanthare madhujitha srithakausthube ya, Visit: http://Divine-Thought.blogspot.com/ Mail us: [email protected] Document Composition: Vishnu Vikram Gunnikuntla Kanakadhara Stotram – http://Divine-Thought.blogspot.com/ Haravaleeva nari neela mayi vibhathi, Kamapradha bhagavatho api kadaksha mala, Kalyanamavahathu me kamalalayaya He who has won over Madhu[4], Wears the Kousthuba[5] as ornament, And also the garland of glances, of blue Indraneela[6], Filled with love to protect and grant wishes to Him, Of her who lives on the lotus, And let those also fall on me, And grant me all that is good. -

SB Saptah Day 1A

www.mahavishnugoswami.com SB Saptah Day 1A - Significance of Purushottama Masa Verse: BG 9.30 Location: Sydney [Maharaj speaking] Hare Krsna Hare Krsna Krsna Krsna Hare Hare / Hare Rama Hare Rama Rama Rama Hare Hare It was not loud enough…. Hare Krsna Hare Krsna Krsna Krsna Hare Hare / Hare Rama Hare Rama Rama Rama Hare Hare Jai, Srila Prabhupada ki Jai… Krsna mercy, <> came to glorify Him. [Maharaj singing, audience repeating] Jaya Radha Madhava Jaya Kunja Bihari (2) Jaya Gopi Jana Vallabha Jaya Girivara Dhari, Jaya Girivara Dhari (2) Jaya Yashoda Nandana Jaya Braja Jana Ranjana, Jaya Braja Jana Ranjana (1) Jaya Jamuna Tiravana Chari, Jaya Kunja Bihari (5) Hare Krsna Hare Krsna Krsna Krsna Hare Hare / Hare Rama Hare Rama Rama Rama Hare Hare (5-7) Krsna Krsna Krsna Krsna Krsna Krsna Krsna Hey (2) Krsna Krsna Krsna Krsna Krsna Krsna Krsna Pahimaam (2) Krsna Krsna Krsna Krsna Krsna Krsna Rashamaam (1) Krsna Keshava Krsna Keshava Krsna Keshava Rashamaam Raam Raghava Raam Raghava Raam Raghava Pahimaam Raam Raghava Raam Raghava Raam Raghava Rashamaam Krsna Krsna Krsna Krsna Krsna Krsna Krsna Hey (4) Hare Krsna Hare Krsna Krsna Krsna Hare Hare / Hare Rama Hare Rama Rama Rama Hare Hare (9-10) Raghupati Raghava Raja Raam Patita Pavana Sita Raam (2) Sita Raam Sita Raam Bhaja Pyare too Sita Rama (1) Raghupati Raghava Raja Raam Patita Pavana Sita Raam (1) Sri Raam Jai Raam Jai Jai Raam Sri Raam Jai Raam Jai Jai Raam (2) Raghupati Raghava Raja Raam Patita Pavana Sita Raam (2) Hare Krsna Hare Krsna Krsna Krsna Hare Hare / Hare Rama Hare Rama Rama -

108 Upanishads

108 Upanishads From the Rigveda 36 Dakshinamurti Upanishad From the Atharvaveda 1 Aitareya Upanishad 37 Dhyana-Bindu Upanishad 78 Annapurna Upanishad 2 Aksha-Malika Upanishad - 38 Ekakshara Upanishad 79 Atharvasikha Upanishad about rosary beads 39 Garbha Upanishad 80 Atharvasiras Upanishad 3 Atma-Bodha Upanishad 40 Kaivalya Upanishad 81 Atma Upanishad 4 Bahvricha Upanishad 41 Kalagni-Rudra Upanishad 82 Bhasma-Jabala Upanishad 5 Kaushitaki-Brahmana 42 Kali-Santarana Upanishad 83 Bhavana Upanishad Upanishad 43 Katha Upanishad 84 Brihad-Jabala Upanishad 6 Mudgala Upanishad 44 Katharudra Upanishad 85 Dattatreya Upanishad 7 Nada-Bindu Upanishad 45 Kshurika Upanishad 86 Devi Upanishad 8 Nirvana Upanishad 46 Maha-Narayana (or) Yajniki 87 Ganapati Upanishad 9 Saubhagya-Lakshmi Upanishad Upanishad 88 Garuda Upanishad 10 Tripura Upanishad 47 Pancha-Brahma Upanishad 48 Pranagnihotra Upanishad 89 Gopala-Tapaniya Upanishad From the Shuklapaksha 49 Rudra-Hridaya Upanishad 90 Hayagriva Upanishad Yajurveda 50 Sarasvati-Rahasya Upanishad 91 Krishna Upanishad 51 Sariraka Upanishad 92 Maha-Vakya Upanishad 11 Adhyatma Upanishad 52 Sarva-Sara Upanishad 93 Mandukya Upanishad 12 Advaya-Taraka Upanishad 53 Skanda Upanishad 94 Mundaka Upanishad 13 Bhikshuka Upanishad 54 Suka-Rahasya Upanishad 95 Narada-Parivrajaka 14 Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 55 Svetasvatara Upanishad Upanishad 15 Hamsa Upanishad 56 Taittiriya Upanishad 96 Nrisimha-Tapaniya 16 Isavasya Upanishad 57 Tejo-Bindu Upanishad Upanishad 17 Jabala Upanishad 58 Varaha Upanishad 97 Para-Brahma Upanishad -

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

Bhoga-Bhaagya-Yogyata Lakshmi

BHOGA-BHAAGYA-YOGYATA LAKSHMI ( FULFILLMENT AS ONE DESERVES) Edited, compiled, and translated by VDN Rao, Retd. General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organization, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, currently at Chennai 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu Essence of Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana Essence of Paraashara Smtiti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Dharma Bindu Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and Austerities- Essence of Manu Smriti*- Quintessence of Manu Smriti* - *Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskara- Essence of Maha Narayanopanishad*-Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi* Note: All the above Scriptures already released on www. -

Eeotheologieal Dimensions of Termite Hill

Eeotheologieal Dimensions of Termite Hill NANDKUMAR KAMAT ECOLOGY is most fundamental to the survival of human cultures and populations. Ecological resources are exploited by humans for creation of an artificial hierarchy of eco-systems. Technologies are evolved for efficient transfer of ecological resources. During this course of material and technological evolution symbols, motifs are absorbed; rituals are formulated, cults emerge through common symbols and rituals; gods and goddesses; demons and devils; spirits and angels assume forms and shapes and religious systems befitting the levels of technology get rooted. Magic is related to technology. Primitive agricultural and fertility magic could be considered as monopolised knowledge of stagnated, unevolved or dynamic technology depending upon the ecological specificity of each culture. The common determinants of ecological specificity of any region are soil and climate.1 The ecological dimensions of historical theology have to be examined from these common determinants. In this regard, the cults of earth-mother worship as found in South Konkan and Goa, could be test cases. Scientific elucidation of these cults and demystification of various beliefs, legends and rituals associated with them is necessary to find the true meaning of several historical phenomena. As A.C. Spawlding says, Hhistorians depend on a type of explanation that they claim is different from scientific explanation. While in fact, no separate form of historical explanation exists. "2 - Many quasi and pseudo-historical forms of explanations3 exist for the cult of Santeri, Ravalnatha, Skanda-Kartikeya, 84 Subhramanya and Muruga, Renuka, Parashurama and Yellamma, Jyotiba, Khandoba and Durga4. Mostly these are propagated through brahminic literature and sometimes through the folklore. -

Upanishad Vahinis

Upanishad Vahini Stream of The Upanishads SATHYA SAI BABA Contents Upanishad Vahini 7 DEAR READER! 8 Preface for this Edition 9 Chapter I. The Upanishads 10 Study the Upanishads for higher spiritual wisdom 10 Develop purity of consciousness, moral awareness, and spiritual discrimination 11 Upanishads are the whisperings of God 11 God is the prophet of the universal spirituality of the Upanishads 13 Chapter II. Isavasya Upanishad 14 The spread of the Vedic wisdom 14 Renunciation is the pathway to liberation 14 Work without the desire for its fruits 15 See the Supreme Self in all beings and all beings in the Self 15 Renunciation leads to self-realization 16 To escape the cycle of birth-death, contemplate on Cosmic Divinity 16 Chapter III. Katha Upanishad 17 Nachiketas seeks everlasting Self-knowledge 17 Yama teaches Nachiketas the Atmic wisdom 18 The highest truth can be realised by all 18 The Atma is beyond the senses 18 Cut the tree of worldly illusion 19 The secret: learn and practise the singular Omkara 20 Chapter IV. Mundaka Upanishad 21 The transcendent and immanent aspects of Supreme Reality 21 Brahman is both the material and the instrumental cause of the world 21 Perform individual duties as well as public service activities 22 Om is the arrow and Brahman the target 22 Brahman is beyond rituals or asceticism 23 Chapter V. Mandukya Upanishad 24 The waking, dream, and sleep states are appearances imposed on the Atma 24 Transcend the mind and senses: Thuriya 24 AUM is the symbol of the Supreme Atmic Principle 24 Brahman is the cause of all causes, never an effect 25 Non-dualism is the Highest Truth 25 Attain the no-mind state with non-attachment and discrimination 26 Transcend all agitations and attachments 26 Cause-effect nexus is delusory ignorance 26 Transcend pulsating consciousness, which is the cause of creation 27 Chapter VI. -

Siya Ke Ram Free Download All Episodes Siya Ke Ram Free Download All Episodes

siya ke ram free download all episodes Siya ke ram free download all episodes. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 66a852ed1f628474 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Siya Ke Ram All Episodes 1-326 Free Download and Watch (Full Review and Cast) Siya Ke Ram All Episode 1-326 Free Download or Watch, Review, and Cast: This is the most popular TV Show in India and Bangladesh. This show presents the epic Ramayana , the story of Lord Rama and Devi Sita from Sita’s perspective. It is premiered on 16 November 2015 and ended on 4 November 2016. Now it is available online. Do you want to watch Siya Ke Ram All Episode? And Searching on the internet? So this website will help you to watch all the episodes without any problem. You can also get full reviews and cast names from here. Anyway, today I am going to share all the methods to watch and download it. -

Raja Ravi Varma 145

viii PREFACE Preface i When Was Modernism ii PREFACE Preface iii When Was Modernism Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India Geeta Kapur iv PREFACE Published by Tulika 35 A/1 (third floor), Shahpur Jat, New Delhi 110 049, India © Geeta Kapur First published in India (hardback) 2000 First reprint (paperback) 2001 Second reprint 2007 ISBN: 81-89487-24-8 Designed by Alpana Khare, typeset in Sabon and Univers Condensed at Tulika Print Communication Services, processed at Cirrus Repro, and printed at Pauls Press Preface v For Vivan vi PREFACE Preface vii Contents Preface ix Artists and ArtWork 1 Body as Gesture: Women Artists at Work 3 Elegy for an Unclaimed Beloved: Nasreen Mohamedi 1937–1990 61 Mid-Century Ironies: K.G. Subramanyan 87 Representational Dilemmas of a Nineteenth-Century Painter: Raja Ravi Varma 145 Film/Narratives 179 Articulating the Self in History: Ghatak’s Jukti Takko ar Gappo 181 Sovereign Subject: Ray’s Apu 201 Revelation and Doubt in Sant Tukaram and Devi 233 Frames of Reference 265 Detours from the Contemporary 267 National/Modern: Preliminaries 283 When Was Modernism in Indian Art? 297 New Internationalism 325 Globalization: Navigating the Void 339 Dismantled Norms: Apropos an Indian/Asian Avantgarde 365 List of Illustrations 415 Index 430 viii PREFACE Preface ix Preface The core of this book of essays was formed while I held a fellowship at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library at Teen Murti, New Delhi. The project for the fellowship began with a set of essays on Indian cinema that marked a depar- ture in my own interpretative work on contemporary art. -

Multidimensional Role of Women in Shaping the Great Epic Ramayana

International Journal of Academic Research and Development International Journal of Academic Research and Development ISSN: 2455-4197 Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 www.academicsjournal.com Volume 2; Issue 6; November 2017; Page No. 1035-1036 Multidimensional role of women in shaping the great epic Ramayana Punit Sharma Assistant Professor, Institute of Management & Research IMR Campus, NH6, Jalgaon, Maharashtra, India Abstract We look for role models all around, but the truth is that some of the greatest women that we know of come from Indian mythology Ramayana. It is filled with women who had the fortitude and determination to stand up against all odds ones who set a great example for generations to come. Ramayana is full of women, who were mentally way stronger than the glorified heroes of this great Indian epic. From Jhansi Ki Rani to Irom Sharmila, From Savitribai Fule to Sonia Gandhi and From Jijabai to Seeta, Indian women have always stood up for their rights and fought their battles despite restrictions and limitations. They are the shining beacons of hope and have displayed exemplary dedication in their respective fields. I have studied few characters of Ramayana who teaches us the importance of commitment, ethical values, principles of life, dedication & devotion in relationship and most importantly making us believe in women power. Keywords: ramayana, seeta, Indian mythological epic, manthara, kaikeyi, urmila, women power, philosophical life, mandodari, rama, ravana, shabari, surpanakha Introduction Scope for Further Research The great epic written by Valmiki is one epic, which has Definitely there is a vast scope over the study for modern day mentioned those things about women that make them great. -

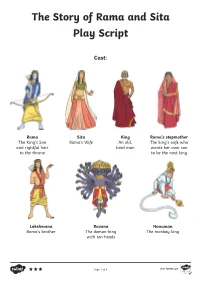

The Story of Rama and Sita Play Script

The Story of Rama and Sita Play Script Cast: Rama Sita King Rama’s stepmother The King’s Son Rama’s Wife An old, The king’s wife who and rightful heir tired man wants her own son to the throne to be the next king Lakshmana Ravana Hanuman Rama’s brother The demon-king The monkey king with ten heads Cast continued: Fawn Monkey Army Narrator 1 Monkey 1 Narrator 2 Monkey 2 Narrator 3 Monkey 3 Narrator 4 Monkey 4 Monkey 5 Prop Ideas: Character Masks Throne Cloak Gold Bracelets Walking Stick Bow and Arrow Diva Lamps (Health and Safety Note-candles should not be used) Audio Ideas: Bird Song Forest Animal Noises Lights up. The palace gardens. Rama and Sita enter the stage. They walk around, talking and laughing as the narrator speaks. Birds can be heard in the background. Once upon a time, there was a great warrior, Prince Rama, who had a beautiful Narrator 1: wife named Sita. Rama and Sita stop walking and stand in the middle of the stage. Sita: (looking up to the sky) What a beautiful day. Rama: (looking at Sita) Nothing compares to your beauty. Sita: (smiling) Come, let’s continue. Rama and Sita continue to walk around the stage, talking and laughing as the narrator continues. Rama was the eldest son of the king. He was a good man and popular with Narrator 1: the people of the land. He would become king one day, however his stepmother wanted her son to inherit the throne instead. Rama’s stepmother enters the stage. -

Interpreting Sati: the Omplexc Relationship Between Gender and Power in India Cheyanne Cierpial Denison University

Denison Journal of Religion Volume 14 Article 2 2015 Interpreting Sati: The omplexC Relationship Between Gender and Power In India Cheyanne Cierpial Denison University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.denison.edu/religion Part of the Ethics in Religion Commons, and the Sociology of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Cierpial, Cheyanne (2015) "Interpreting Sati: The ompC lex Relationship Between Gender and Power In India," Denison Journal of Religion: Vol. 14 , Article 2. Available at: http://digitalcommons.denison.edu/religion/vol14/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Denison Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denison Journal of Religion by an authorized editor of Denison Digital Commons. Cierpial: Interpreting Sati: The Complex Relationship Between Gender and P INTERPRETING SATI: THE COMPLEX RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN GENDER AND POWER IN INDIA Interpreting Sati: The Complex Relationship Between Gender and Power In India Cheyanne Cierpial A recurring theme encountered in Hinduism is the significance of context sensitivity. In order to understand the religion, one must thoroughly examine and interpret the context surrounding a topic in Hinduism.1 Context sensitivity is nec- essary in understanding the role of gender and power in Indian society, as an exploration of patriarchal values, religious freedoms, and the daily ideologies as- sociated with both intertwine to create a complicated and elaborate relationship. The act of sati, or widow burning, is a place of intersection between these values and therefore requires in-depth scholarly consideration to come to a more fully adequate understanding. The controversy surrounding sati among religion schol- ars and feminist theorists reflects the difficulties in understanding the elaborate relationship between power and gender as well as the importance of context sen- sitivity in the study of women and gender in Hinduism.