Arxiv:2106.12490V1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

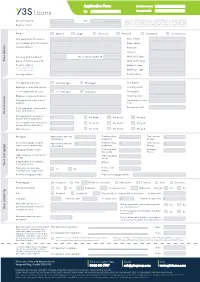

Y3s Intermediary Agreement for Regulated Mortgage Contracts

Y3S INTERMEDIARY AGREEMENT FOR REGULATED MORTGAGE CONTRACTS Parties (1) B2B Loans & Mortgages Ltd trading as Y3S Loans (including miLoanbroker.com) incorporated and registered in England and Wales with company number 5752425 whose registered office is at 9-10 Neptune Court, Vanguard Way, Cardiff, CF24 5PJ (“Y3S”); Background (A) The Intermediary has a large number of contacts, and can meet further contacts who may be interested in applying for a Regulated Mortgage (defined below) from Y3S. (B) Y3S wishes to be introduced to such Applicants by telephone or via the Website (both defined below) and is willing to pay the Intermediary remuneration on the terms of this agreement if such Applicants purchase services from Y3S.The Intermediary is willing to introduce Applicants to Y3S in return for remuneration as specified in this agreement. Agreed terms 1. The following definitions and rules of interpretation apply in this agreement. 1.1 Definitions: Applicable Legislation the Consumer Credit Acts 1974 and 2006 (‘CCA’), the Data Protection Act 1998 (‘DPA’), the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (‘FSMA’), the rules of the Financial Conduct Authority(‘FCA’) including the European Mortgage Credit Directive (EMCD) and all other applicable statutes and regulations as well as any relevant guidance issued by regulators; © miLoan 2016. Y3S Group Ltd. Applicant an individual who is interested in and/or suitable for a Regulated Mortgage contract and in respect of whom Applicant Data is supplied by the Intermediary to Y3S whether via the Website or -

RZR-P RZQ-P Service Manual

SiUS281117 Service Manual RZR-P, RZQ-P(9) Series Cooling Only / Heat Pump R-410A 60Hz SiUS281117 RZR-P, RZQ-P(9) Series Cooling Only / Heat Pump R-410A 60Hz ED Reference For items below, please refer to Engineering Data. For except FTQ No. Item ED No. Page Remarks 1 Specification - Cooling Only EDUS281120 p. 7-13 2 Specification - Heat Pump EDUS281120 p. 14-20 3 Option List EDUS281120 p. 100-102 For FTQ No. Item ED No. Page Remarks 1 Specification - Heat Pump EDUS281008 p. 4 2 Option List EDUS281008 p. 60 1. Safety Considerations.............................................................................v 1.1 Safety Considerations for Repair ............................................................. v 1.2 Safety Considerations for Users ..............................................................vi Part 1 General Information........................................................... 1 1. Model Names and Power Supply............................................................2 1.1 Cooling Only ............................................................................................2 1.2 Heat Pump ...............................................................................................2 2. External Appearance ..............................................................................3 2.1 Indoor Units..............................................................................................3 2.2 Remote Controller....................................................................................4 2.3 Outdoor Units...........................................................................................4 -

Electric Conduction at an Interface. Hung-Chi Chang Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1953 Electric Conduction at an Interface. Hung-chi Chang Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Chang, Hung-chi, "Electric Conduction at an Interface." (1953). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8039. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8039 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ELECTRIC CONDUCTION AT AN INTERFACE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Physics by Hung-Chi Chang B 0 So9 National Chiao-Tung University, Shanghai, China, 1934 Mo So, Louisiana State University, 1951 June, 1953 UMI Number: DP69417 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI Dissertation Publishing UMI DP69417 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Advanced Nuclear Physics and Chemistry Experiments

DOCOIMW IES 60 AUTHOR Duggan, Jerome L.; An Ethers TITLE Advanced Experimilmts Nuclear Science, Advanced Nuclear 'Physics and Chemistry Experiments. SPONS,AGENCY National Science Foundation,Washington, L.C., North Texas State Univ., Denton. BUREAU NO NSF-SED-74-20286 PUB. DATE 17 ?) NOTE 258p.; Contains Occasicna and broken type ROES PRICE HP-$0..8;5 Plus Postage. HC, Not Available fxo ED VESCRIPTIS Chemistry; College Science; *Giadmate StaCy; H Education; Instructional Haterials; Laboratory Procedures; *NclearEhysics; Physics; Science Education; *Science Fxpeciaerts ABSTRACT The experiments in this anualrepresent state-of-the-art techniques which should Le within thebudgetary_ constraints Of a college 'physics or chewistry department. There are fourteen experiments divided into five modules. The modules are on X-ray fluorescence, charged particle detection, neutron activation analysis, X-ray attenuation, and accelerator experiments.' Each module contains an introduction, a guide to the types cf experiments contained, learning objectivcs,and a list of- prerequisite skills. Each experiment contains objectives, ar introduction, a'list of equipment, .data accumulation and analysis procedures, discussion of results; post-test questions, computer programs, o'ticnal work, and references. (Author/BB) ****** ***, **** ** *** ** ** * ****** * Re prod upplied by EDES are the best thatCEEto made from the original document. * * * * ***** *** * * * * * * * * *a * * * * * * * * * ** * * * -* Advaticed EiperimentsIii Nuclear Science T Vokorne I Advanced Nuclear:Physics And Chemistry Experiments oronr L. Duggan, Floyd D. McDaniel, and Jack G. itehn This Projett IS:Supported Jointly By The Nation4 Science Foundation And 1+ rtl Tias State University Denton, Texas 76203 INTRODUcTiO1 Many colleges and'universities throughout the-United Stateshave recognized the iMpo- nee of the study of nuclear science-and# radio- isotopes in the undqrgraduate curriculum. -

Zero Drift, Unidirectional Current Shunt Monitor AD8219

Zero Drift, Unidirectional Current Shunt Monitor AD8219 FEATURES FUNCTIONAL BLOCK DIAGRAM High common-mode voltage range VS 4 V to 80 V operating R4 −0.3 V to +85 V survival LDO R1 Buffered output voltage –IN OUT Gain = 60 V/V +IN R2 Wide operating temperature range: −40°C to +125°C R3 Excellent ac and dc performance AD8219 ±100 nV/°C typical offset drift GND ±50 µV typical offset 09415-001 ±5 ppm/°C typical gain drift Figure 1. 110 dB typical CMRR at dc APPLICATIONS High-side current sensing 48 V telecom Power management Base stations Unidirectional motor control Precision high voltage current sources GENERAL DESCRIPTION The AD8219 is a high voltage, high resolution, current shunt The AD8219 offers breakthrough performance throughout amplifier. It features a set gain of 60 V/V, with a maximum the −40°C to +125°C temperature range. It features a zero ±0.3% gain error over the entire temperature range. The drift core, which leads to a typical offset drift of ±100 nV/°C buffered output voltage directly interfaces with any typical throughout the operating temperature and common-mode converter. The AD8219 offers excellent input common-mode voltage range. Special attention is devoted to output linearity rejection from 4 V to 80 V. The AD8219 performs unidirectional being maintained throughout the input differential voltage range, current measurements across a shunt resistor in a variety of regardless of the common-mode voltage present, while the industrial and telecom applications including motor control, typical input offset voltage is ±50 μV. power management, and base station power amplifier bias The AD8219 is offered in a 8-lead MSOP package. -

Application Form Bedrooms Employed Employed Per Week Per Week Per Week If Flat,No

Application Form Introducer name Ref Contact in Y3S Amount required Term Y3S Loans is a trading name of b2b Loans & Mortgages Ltd. A company registered in £ months/years England no. 5752425. Registered office: Units 9-10, Neptune Court, Vanguard Way, Cardiff, CF24 5PJ. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. All Purpose of loan loans are secured on property and are subject to credit and age status restrictions. Are you Married Single Divorced Widowed Separated Common Law First applicant’s full name(s) Date of birth Second applicant’s full name(s) Date of birth Current address Postcode Home tel How long at this address? No. of children under 18 Work tel (1st app) nd Your details Your Age(s) of children under 18 Work tel (2 app) Previous address Mobile (1st app) (if at current address nd less than three years) Mobile (2 app) Security address Email address First applicant, are you Self-employed Employed Occupation Employer’s name and address How long in job Second applicant, are you Self-employed Employed Occupation Employer’s name and address How long in job First applicants bank name/ Time bank account address held If self employed, accountant’s Accountant’s tel name and address Your income Your First applicant’s total gross £ Per week Per month Per year income before deductions Second applicant’s total gross £ Per week Per month Per year income before deductions Other income £ Per week Per month Per year Mortgage Approximate amount £ Total monthly £ Total arrears £ outstanding payments (if any) Second mortgage or other Approximate amount £ Total monthly £ Total arrears £ loan secured on property outstanding payments (if any) Mortgage lender’s name How long with Mortgage this lender A/C no. -

Annex to Volume Vii

This electronic version (PDF) was scanned by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Library & Archives Service from an original paper document in the ITU Library & Archives collections. La présente version électronique (PDF) a été numérisée par le Service de la bibliothèque et des archives de l'Union internationale des télécommunications (UIT) à partir d'un document papier original des collections de ce service. Esta versión electrónica (PDF) ha sido escaneada por el Servicio de Biblioteca y Archivos de la Unión Internacional de Telecomunicaciones (UIT) a partir de un documento impreso original de las colecciones del Servicio de Biblioteca y Archivos de la UIT. (ITU) ﻟﻼﺗﺼﺎﻻﺕ ﺍﻟﺪﻭﻟﻲ ﺍﻻﺗﺤﺎﺩ ﻓﻲ ﻭﺍﻟﻤﺤﻔﻮﻇﺎﺕ ﺍﻟﻤﻜﺘﺒﺔ ﻗﺴﻢ ﺃﺟﺮﺍﻩ ﺍﻟﻀﻮﺋﻲ ﺑﺎﻟﻤﺴﺢ ﺗﺼﻮﻳﺮ ﻧﺘﺎﺝ (PDF) ﺍﻹﻟﻜﺘﺮﻭﻧﻴﺔ ﺍﻟﻨﺴﺨﺔ ﻫﺬﻩ .ﻭﺍﻟﻤﺤﻔﻮﻇﺎﺕ ﺍﻟﻤﻜﺘﺒﺔ ﻗﺴﻢ ﻓﻲ ﺍﻟﻤﺘﻮﻓﺮﺓ ﺍﻟﻮﺛﺎﺋﻖ ﺿﻤﻦ ﺃﺻﻠﻴﺔ ﻭﺭﻗﻴﺔ ﻭﺛﻴﻘﺔ ﻣﻦ ﻧﻘﻼ ً◌ 此电子版(PDF版本)由国际电信联盟(ITU)图书馆和档案室利用存于该处的纸质文件扫描提供。 Настоящий электронный вариант (PDF) был подготовлен в библиотечно-архивной службе Международного союза электросвязи путем сканирования исходного документа в бумажной форме из библиотечно-архивной службы МСЭ. © International Telecommunication Union XVII A.R DUSS6LDORF 21.5 - 1.6 1990 CCIR XVIIth PLENARY ASSEMBLY DUSSELDORF, 1990 NTERNATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATION UNION REPORTS OF THE CCIR, 1990 (ALSO DECISIONS) ANNEX TO VOLUME VII STANDARD FREQUENCIES AND TIME SIGNALS CCIR INTERNATIONAL RADIO CONSULTATIVE COMMITTEE Geneva, 1990 XVII A.R DUSS6LDORF 21.5 - 1.6 1990 CCIR XVIIth PLENARY ASSEMBLY DUSSELDORF, 1990 NTERNATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATION UNION REPORTS OF THE CCIR, 1990 (ALSO DECISIONS) ANNEX TO VOLUME VII STANDARD FREQUENCIES AND TIME SIGNALS CCIR INTERNATIONAL RADIO CONSULTATIVE COMMITTEE 92-61-04231-7 Geneva, 1990 © I.T.U. ANNEX TO VOLUME VII STANDARD FREQUENCIES AND TIME SIGNALS (Study Group 7) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Plan of Volumes I to XV, XVIIth Plenary Assembly of the CCIR (see Volume VII - Recommendations) ................................... -

Hello, You Lovely Bunch of Y3s!

Hello, you lovely bunch of Y3s! You’ve done it! Another week done and dusted and we honestly couldn’t be prouder of you all. We can’t wait to see all of you and we are missing you immensely. Keep sending us all of your lovely work and photos to our emails as it is certainly keeping us smiling. We hope that you have enjoyed looking at ‘The Stone Age Boy’ and learning more about the Stone Age. It’s very interesting. If you haven’t managed to read the entire story then make sure you continue to read it. It’s full of fascinating facts and explains a lot about the Stone Age. This week we are going to continue with the Stone Age and looking at the ‘Stone Age Boy’ text. We also have lots of other activities for you to have a go at. Please remember to just try your best and we are all so proud of you. Stay safe, keep washing those hands and enjoy your home learning. From all of your Y3 teachers. English - WEEK 9 – 08.06.20 Daily Tasks Reading Make sure you read at least 4 times this week. Continue to record your reading in your diary. You can also take it in turns to read with a parent or sibling too. This week whilst you are reading, you might like to - Write a diary entry as if you are one of the characters. - Magpie all of the impressive vocabulary that you see to use in your writing. - Draw your favourite character and add information about that character around the outside. -

0*? Tjusfcce- Iubt Alo*- Cjf) 3Fo J Ini N R

0*? tjusfcce- iUbt Alo*- Cjf) 3fo J Ini n r Ji / 75 ? //4i, (/ £/j-/ Ji nh i n > ~Th cJ >2^3 'To ]/\euj uj&ojhh r sccJ<?> & vurCf- toC^-rt kou^- TeinninJ ?, ~rhow\^<. t ju<>hc<L 17^ TtsntCt $0/ Jenviivitfj5/ Q^rftecl -io C-i. 4$ liio^e^ 17^/ JUU COURT ^or Uw. Fo^.a A^«vC4 3^3 II " So.*-<i.li cola ii I, « TV|0H1<»S jli<.u5 174.2 M^C4 ,4^0 ii !• KKHU Pa^c K ,, IToLir Uk :: . TlteiiAi DrJ. V' MUn (Jiiert 17 6 X MAR CO J :i 7/ W OjU ^r-VTiLc| [O' 0^2 (iXLcr-)Ttx^ 5&^V1 v \(^r(Jvu^i' . \tl^l. v^cu^w '$n> i (UUrvU^ [ftS ' W««i. ^oTTletilj^DX-S. ^U^V-r dj ^(oi^ lillor^xj '{X' \JJ-»^<J'i^/. ^VJLV^t. <$ ^ S t®3> ail C7»^U;U A»-? ‘Str^vx A*.") aJ nG-t ji- uju.<n \i_m ^x)- C^Vi (i’^l- i*U| Ota $i&S ^o-;- ir ^ d ^Vy\ ^Lv% n^i v^oo. i &-it/\ \ U-^yv-v^ O t»X VljCL> c C Jt . GJG'1 Vlu^us^vui -vW '-W-fiv' (4t>1< <*H 1 dWv CWCavio^; ’ (C-4G-W7 U. S %\ O'rvi ii tXo-8-d GH7- cAixl <-S2V7 UjlWvlc4~ ' £>S S "STs 3 - ^ A T^fVM^^Tf bSfy " Jennings, Thomas attorney for Thomas Hartley & Sons 1763 Mar. ct., 711. attorney for Thomas Caney 17$3llar. ct, 720-22 attorhy for A^n Sligh 1763 Mar. ct., 722-23 attorney for Cornelius Howard " " 7^2— /9rr/ S- poa-iij J7t> 7 /7^. -

The Shepherd of Israel

THE SHEPHERD OF ISRAEL Subscription Price Vol. XXIII No. 3 50 Cents a Year. JOSEPH HOFFMAN COHN, Editor NOVEMBER, 1940 to solve his own problems and protect his bodies have pledged their co-operation. own interests. We can only hope that he \V e now introduce to you the world's HE WORLD 'S LAST B:L,OADCAST will be left to himself to carry on his am- greates dictator with headquarters at bitious program of internal development. Rome." (Adapted from a Radio talk by Rev. J. F. Holliday, B.A., a Christian pastor of Hamilton Then our radio listener will twin the Then the radio listener Nvill hold his Ontario, and a profound lover of the Jews; dial a bit until he catches the crisp, racy breath while the Anti-Christ, the Man of with additions and revisions by the Editors) tones of an American newspaper reporter, Sin, the one who counterfeits the Lord who will be saying something like this: outlines his program to the Do you "listen in" to the news-casts? "There's more in Britain's surrender world. tie will hear this Supreme Auto- Of course you do, and every time you of the Mandate over Palestine than may crat demand the support of every man catch the news-laden ether WilVe& in your at first appear. For years the Holy Land and woman on the globe. He will hear of radio receiving set, they remind you that has been a source of worry to John Bull. the inauguration of an economic program you are living in a world of chaos and Germany and Italy have both been active that will lift the depression and finish un- commotion, a world of selfishness and with anti-British propaganda, sowing, cent cooperation which will be enforced suspicion, a world weighted with woe, a with considerable success the seeds of fer- by the use of a mark, like the caste marks world reverberating with the tramp of ment among the Arabs in and around Pa- of India, or the fastio of Italy, or the armed feet, a world that. -

STANDARD FREQUENCY and TIME SIGNAL STATIONS on LF and HF Originally Published Between October 1997 and July 1998

WUN ARCHIVE STANDARD FREQUENCY AND TIME SIGNAL STATIONS ON LF AND HF Originally published between October 1997 and July 1998 Standard frequency and time signal stations on LF and HF, pt.1 Welcome to the first part of a series about Time and Frequency Stations on LF and HF. This month you'll find a frequency list and a general introduction to these stations. During the next few months, we will highlight a bunch of the stations. Special thanks to Klaus Betke for his research, Stan Skalsky, Kevin Carey, Terry Krey, and Dave Mills. Also thanks to the Institute of Meteorology for Time and Space (Russia), BIPM Bureau International des Poids et Mesures (France) and NIST National Institute of Standards and Technology (USA) for their time, help and the huge amount of info. Introduction Exact time intervals are needed for navigation and surveying, in science and engineering. In the past, HF radio signals were often the only way to calibrate a clock onboard a ship or a frequency standard in a laboratory. In the age of GPS satellites and portable atomic clocks, however, time and frequency distribution via HF has become largely obsolete. New applications like network synchronization require an accuracy that cannot be met by HF signals. Moreover, the transmission scheme of most stations and the peculiarity of shortwave propagation make these signals less suitable for automatic, unattended reception. Consequently, many time signal stations have disappeared. In former times, coastal radio stations also transmitted time signals on their CW frequencies. Although numerous of these services to mariners are still listed in, you will hardly find an active one. -

•Rrl'00039 ORIGINAL Site Name; Bush Valley Landfifp"' TDD No.: F3-8405-44

,f • •" - R-585-6-5-5 SITE INSPECTION OF BUSH VALLEY LANDFILL PREPARED UNDER TDD NO. F3-8405-44 ERA NO. MD-02 CONTRACT NO. 68-01-6699 •:' . FOR THE HAZARDOUS SITE CONTROL DIVISION U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY DECEMBER 10, 1985 ,NUS CORPORATION SUPERFUND DIVISION SUBMITTED BY REVIEWED BY APPROVED RICHARD CALLAHAN WILLIAM WENTWORTH G/R'TH GLENN' ENVIRON. ENGINEER ASSISTANT MANAGER MANAGER, FIT III •RRl'00039 ORIGINAL Site Name; Bush Valley LandfifP"' TDD No.: F3-8405-44 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE 1,0 INTRODUCTION 1-1 1.1 AUTHORIZATION 1-1 1.2 ' SCOPE OF WORK 1-1 1.3 SUMMARY 1-1 2.0 THE SITE 2-1 2.1 LOCATION 2-1 2.2 SITE LAYOUT 2-1 2.3 OWNERSHIP HISTORY 2-2 2.1. SITE USE HISTORY 2-2 2.5 PERMIT AND REGULATORY ACTION HISTORY 2-2 2.6 REMEDIAL ACTION TO DATE 2-3 3.0 ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING 3-1 3.1 WATER SUPPLY 3-1 3.2 SURFACE WATERS 3-1 3.3 GEOLOGY AND SOILS 3-2 3.4 GROUNDWATERS 3-3 3.5 CLIMATE AND METEOROLOGY 3-3 3.6 LAND USE 3-4 3.7 POPULATION DISTRIBUTION 3-4 3.8 CRITICAL ENVIRONMENTS 3-4 4.0 WASTE TYPES AND QUANTITIES 4-1 5.0 FIELD TRIP REPORT 5-1 5.1 SUMMARY 5-1 5.2 PERSONS CONTACTED 5-1 5.2.1 PRIOR TO FIELD TRIP 5-1 5.2.2 AT THE SITE 5-1 5.3 SAMPLE LOG 5-3 5.4 SITE OBSERVATIONS 5-4 5.5 PHOTOGRAPH LOG 5.6 EPA SITE INSPECTION FORM 6.0 LABORATORY DATA 6-1 6.1 SAMPLE DATA SUMMARY 6-1 6.2 QUALITY ASSURANCE REVIEW 6-2 6.2.1 ORGANIC 6-2 6.2.2 ' INORGANIC - 6-4 7.0 TOXICOLOGICAL EVALUATION 7-1 7.1 SUMMARY 7-1 7.2 DISTRIBUTION OF CONTAMINANTS 7-2 7.3 TOXICOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS •ARIOOO7-5 A ,W _, ii r.! £ ! *t H, i " ' i, n u Site Name; Bush Valley Landfill TDD No.: F3-8405-44 APPENDICES A 1.0 COPY OF TDD A-l B 1.0 MAPS AND SKETCHES B-l 1.1 SITE LOCATION MAP 1.2 SITE SKETCH 1.3 SAMPLE LOCATION MAP 1.* PHOTOGRAPH LOCATION MAP 1.5 OFF-SITE LOCATION MAP C 1.0 QUALITY ASSURANCE C-l SUPPORT DOCUMENTATION D 1.0 LABORATORY DATA SHEETS D-l E 1.0 CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF REGULATORY E-l .