PDF Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tiere Und Pflanzen Der Innerstädtischen Grünfläche Fürstenberg in Konstanz

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Berichte der naturforschenden Gesellschaft zu Freiburg im Breisgau Jahr/Year: 2007 Band/Volume: 97 Autor(en)/Author(s): Herrmann Mike, Kleß Jürgen, Schmitz Gregor, Genser Hugo Artikel/Article: Tiere und Pflanzen der innerstädtischen Grünfläche Fürstenberg in Konstanz. Übersicht - seltene Arten - Naturschutz 117-132 © Naturforschende Gesellschaft zu Freiburg im Breisgau c/o Institut für Geo- und Umweltnaturwissenschaften; download www.zobodat.at Ber. Naturf. Ges. Freiburg i. Br., 97/1, S. 117 132, Freiburg 2007 Tiere und Pflanzen der innerstädtischen Grünfläche Fürstenberg in Konstanz. Übersicht - seltene Arten - Naturschutz Mike Herrmann, Jürgen Kleß & Gregor Schmitz Stichwörter Konstanz, Fürstenberg, Drumlin, Fauna, Flora, Landschaftswandel, Artenvielfalt, Verinselung Zusammenfassung Der 3,4 ha große Drumlin Fürstenberg im Konstanzer Stadtgebiet ist zur Hälfte mit arten reichen Magerwiesen, zur anderen Hälfte mit Gehölzen bestanden. Die ehemaligen Heu wiesen wurden über Jahrzehnte nicht gepflegt und gingen großflächig in Brachestadien und Gehölzdickichte über, bis Ende 2002 Maßnahmen zur Entbuschung und Wiesenpflege eingeleitet wurden. Bei der Erfassung der Flora und Fauna, welche hauptsächlich von 2003 bis 2005 stattfand, wurden auf dem Fürstenberg insgesamt 265 Pflanzen- und 549 Tierarten nachgewiesen. Von diesen sind 123, das ist mehr als jede siebte Art, in den Roten Listen der gefährdeten Tiere und Pflanzen geführt. Unter den seltenen Arten befinden sich mehrere, die Relikte der historischen Wiesennutzung sind. Höhere Pflanzen, Tagfalter, Heuschrecken, Wanzen, Wildbienen, Wespen und Schnecken sind besonders umfassend bearbeitet worden. Obwohl das Gebiet stark isoliert liegt und eine stete Freizeitnutzung erfährt, wird aufgrund der wie der eingeführten Wiesenpflege und der kleinklimatisch günstigen Geomorphologie eine positive Prognose für den Arten- und Naturschutz erstellt. -

Building the Temple of Salomo in the Early Medieval „Alamannia“

Journal of Liberal Arts and Humanities (JLAH) Issue: Vol. 1; No. 4; April 2020 pp. 163-185 ISSN 2690-070X (Print) 2690-0718 (Online) Website: www.jlahnet.com E-mail: [email protected] Building the Temple of Salomo in the Early Medieval „Alamannia“ Dr. Thomas Kuentzel M.A. Untere Masch Strasse 16 Germany, 37073 Goettingen E-mail: [email protected] The diocese of Constance is one of the largest north of the Alps, reaching from the Lakes of Thun and Brienz down to Stuttgart and Ulm, from the river Iller (passing Kempten) to the Rhine near Lörrach and Freiburg. Its origins date back to the end of the 6th century; when saint Gall came to the duke of Alamannia, Gunzo, around the year 613, the duke promised him the episcopate, if he would cure his doughter.i In the 9th century some of the bishops also were abbots of the monasteries on the Island Reichenau and of Saint Gall. Three of the bishops were called Salomon, one being the uncle of the following.ii The noble family they belonged to is not known, but they possessed land on the southern shore of Lake Constance, in the province of Thurgau. Salomon III. was educated in the monastery of Saint Gall, and prepared especially for the episcopate. Maybe his uncle and granduncle also benefitted from such an education. Even their predecessor, bishop Wolfleoz, started his career as monk in Saint Gall. It is likely that the three Salomons were given their names with the wish, that they once would gain this office. -

The Corporate Governance of Benedictine Abbeys - What Can Stock Corporations Learn from Monasteries?

1 The corporate governance of Benedictine abbeys - What can stock corporations learn from monasteries? - Katja Rost, Institute of Organization and Administrative Science, University of Zurich, Switzerland, [email protected], Universitätsstrasse 84, CH-8006 Zurich, Switzerland Katja Rost is a research assistant at the Institute of Organization and Administrative Science at the University of Zurich. She obtained her PhD in 2006 on the topic of social capital and innovation and currently does her habilitation in the area of corporate governance. Emil Inauen, Institute of Organization and Administrative Science, University of Zurich, Switzerland, [email protected], Universitätsstrasse 84, CH-8006 Zurich, Switzerland Emil Inauen is a PhD student at the Institute of Organization and Administrative Science and the Institute for Empirical Research in Economics at the University of Zurich. His primary research interest is the economics of religion. Before starting his study of economics he worked as a teacher of religion for several years and has experienced the monastic life. Margit Osterloh, Institute of Organization and Administrative Science, University of Zurich, Switzerland, [email protected], Universitätsstrasse 84, CH-8006 Zurich, Switzerland Margit Osterloh is Professor of Organization at the University of Zurich and Research Director of CREMA - Centre for Research in Economics, Management and the Arts, Switzerland. Her primary research interests include organizational theory, knowledge management, corporate governance and motivational theory. Bruno S. Frey, Institute for Empirical Research in Economics, University of Zurich, Switzerland, [email protected], Winterthurerstrasse 30, CH-8006 Zurich, Switzerland Bruno S. Frey is Professor of Economics at the University of Zurich and Research Director of CREMA - Centre for Research in Economics, Management and the Arts, Switzerland. -

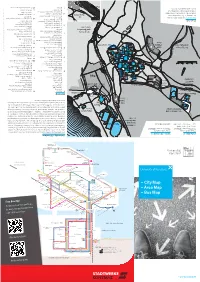

– City Map – Area Map – Bus

09.03.2015 10:13:18 09.03.2015 1 Lage-Stadt-Bus-Flyer_2015_engl.indd – uni-konstanz.de – Android handsets Android 908 Ostwind Lokalzone Kreuzlingen Lokalzone Ostwind Tarifzonengrenze Hauptzoll Tarifzonengrenze 908 Bodanplatz Schnetztor Haltestelle wird von dieser Linie nicht bedient nicht Linie dieser von wird Haltestelle X X 1 9B Haltestelle wird von dieser Linie nur in eine Richtung angefahren Richtung eine in nur Linie dieser von wird Haltestelle 9A 14 Döbele 12 2 Haltestelle wird nur in eine Richtung angefahren Richtung eine in nur wird Haltestelle 3 6 X 5 X (näheres entnehmen Sie bitte dem Fahrplan) dem bitte Sie entnehmen (näheres Döbelestr. Bodanplatz Nur zeitweiliger Linienbetrieb zeitweiliger Nur Nachtschwärmer Legende Hieronymusgasse Schulthaißstr. Lutherplatz 4 1 13 2 1 908 9B 1 9A 3 2 4 Tarifzonengrenze 6 5 4 Brüelstr. Bahnhof 13 908 Tarifzonengrenze iPhone handsets iPhone Marktstätte 6 9B 2 Stephansschule Bürgerbüro 908 9A 13 3 2 Stadtzentrum Paradies 14 6 4 12 3 12 14 5 1 6 BSB/Der Katamaran KN/FN Katamaran BSB/Der Konzilstraße 9B Gymnasium Ellenrieder 1 Gartenstr. Konzilstraße/Theater Gartenstr. Schänzle-Sporthalle/ Laube Niederburg Laube Schottenplatz VHB - City - Zone Konstanz Zone - City - VHB HTWG Wessenbergschule 5 6 3 2 12 14 9B 1 9A Bodensee-Therme Konstanz Bodensee-Therme one of these codes: codes: these of one Spanierstr. Sternenplatz Sternenplatz 4 1 13 2 1 908 9B Kliniken Schmieder Kliniken Hallenbad 9A 5 4 1 3 2 / to use journey planner from from planner journey use to Sternenplatz Rosenau Freibad Horn Freibad Tenbrinkstr. Hebelstr. 6 Markgrafenstr. Line-Eid-Str. Download our free and easy easy and free our Download Stromeyersdorf Gottmannplatz 6 Neuwerk Bodensee Stadion Bodensee Rudolf-Diesel-Str. -

ECOLUP Guide in English

ECOLUP-GUIDANCE Environmental Management for Communal Urban Land Use Planning A publication of the Lake Constance Foundation, Constance www.bodensee-stiftung.org, www.ecolup.info With the support of the European Union LIFE Programme The contents of this guidance have been correctly represented to the best of our knowledge. The editor is not responsible for any mistakes that may be present. Presentations held at project workshops were used for this guidance. The authors are credited to the best of our knowledge. Otherwise, the gist of their contents has been used without reference to the authors in the text. Editor: Editorial Team: Cover + Design: Bodensee-Stiftung Lake Constance Foundation, DERKOHLER & PARTNER Paradiesstraße 13 Constance: Design interdisciplinaire, D-78462 Konstanz Marion Hammerl, Daniela Paas, Constance, www.derkohler.com Uta Strothotte, Thomas Körner Tel.: 0049-(0)7531-9098-0 Printer: Nürtingen University, Institute for Email: [email protected] oder Druckerei Krammer, Applied Research (IAF): Radolfzell-Böhringen, März 2004 [email protected] Wolfgang Everts, Britta www.ecolup.info oder Steinerstauch, Katja Siegmann CD-Rom produced by: MAUS Interaktiv GmbH, Constance www.bodensee-stiftung.org Austrian Institute of Ecology ECOLUP Project Direction: (ÖÖI), Bregenz: Karin Klas, Katrin Löning Marion Hammerl, Bodensee-Stiftung Schereer, Schnell, Walser and Partner (SSWP), Constance: Expert Consultants: Klaus-Dieter Schnell Nürtingen University, Institute for Applied Research (IAF) and the speakers at the Prof. Dipl.-Ing. -

Alison I. Beach

Alison I. Beach St Andrews Institute of Medieval Studies email: [email protected] 71 South St. web: http://www.abeach.org St Andrews blog: http://www.scriptrix.org KY16 9QW Fife Scotland Professional Experience Regular Faculty Positions University of St Andrews, St Andrews, Scotland Professor of Mediaeval History 2020— The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH Professor of History 2019—2020 Resident Director, History and Archaeology of Medieval Ireland Study Course 2013—2019 (with the Irish Archaeology Field School) Associate Professor of History (with tenure) 2013—2019 Assistant Professor of History 2011—2013 Universität zu Köln, Cologne, Germany apl. Professor of Medieval History 2009—2011 College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA Associate Professor of Religious Studies (with tenure) 2006—2009 Director, Program in Medieval & Renaissance Studies 2005—2008 Assistant Professor of Religious Studies 2001—2006 Visiting Positions Columbia University, New York, NY Adjunct Associate Professor, Department of Religion Fall 2018 Universität Bonn, Bonn, Germany Guest Scholar, Katholisch-Theologische Fakultät, Institut für Kirchengeschichte Fall 2017, Spring 2005, and 2006—2007 Guest Scholar, Historisches Seminar Summer 2001 and Fall 2004 Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, NJ Visitor, School of Historical Studies June-July 2017 Member, School of Historical Studies 2013—2014 Postdoctoral Research Assistant to Professor Giles Constable 1998—2000 Universität Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany Guest Scholar, Sonderforschungsbereich 923 (“Bedrohte Ordnungen”) Jan-Feb 2016 Princeton Theological Seminary, Princeton, NJ Guest Scholar 2014—2015 Universität Konstanz, Constance, Germany Guest Professor, Medieval History July 2014 Universität Trier, Trier, Germany DAAD Guest Professor, Medieval History 2008—2009 Temple University, Philadelphia, PA Visiting Assistant Professor of History 2000—2001 New Brunswick Theological Seminary, New Brunswick, NJ Visiting Assistant Professor 1997—1998 Union Theological Seminary, New York NY Visiting Lecturer 1996 Alison I. -

Drunken Brawls in Brothels: Cheap Wine, Court Records, and Other Disreputable Aspects of the Economic History of Constance and Its Region

Drunken Brawls in Brothels: Cheap wine, court records, and other disreputable aspects of the economic history of Constance and its region Josh Burson Paper presented at the German Historical Institute's medieval history seminar London, October 2009 Citation: Burton, J. (2009, October). Drunken Brawls in Brothels: Cheap wine, court records, and other disreputable aspects of the economic history of Constance and its region. Medieval history seminar conducted at the 6th Annual Conference at the German Historical Institute, London, United Kingdom. Josh Burson, “Drunken Brawls in Brothels”, p. 1 “Drunken Brawls in Brothels: Cheap wine, court records, and other disreputable aspects of the economic history of Constance and its region.” In 1456, the records of the City Council of Constance memorialized a fight in a brothel. A certain Burk Brüd had drawn a knife (in itself a punishable offense within city limits) and wounded one Heinrich Appenzeller, for which he was fined four silver marks and sentenced to two months in jail.1 The source of the quarrel is not recorded, although given the multiple functions of houses of prostitution in the period (and the nature of their clientele in any age), it is likely that alcohol was involved. Such cases were very much the norm for the court, which sentenced participants in brawls and knife fights with some regularity. What makes this particular fight noteworthy is the light that it sheds on the subject of my own research: the many and varied ties that connected Constance to the countryside and the wider region around it. In this case, both participants in the fight were from out of town; and their appearance in the city’s criminal records—along with that of many of their contemporaries—gives us essential information about who came to Constance in the fifteenth century, and also hints at other aspects of the relationship between town and countryside. -

Reinterpreting Prone Burials During the Middle Ages and Early Modern Period in German-Speaking Europe

PLOS ONE RESEARCH ARTICLE Between belief and fear - Reinterpreting prone burials during the Middle Ages and early modern period in German-speaking Europe 1,2 2 3 1 Amelie AlteraugeID , Thomas Meier , Bettina Jungklaus , Marco MilellaID , 1 Sandra LoÈ schID * 1 Department of Physical Anthropology, Institute of Forensic Medicine, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland, 2 Institute for Pre- and Protohistory and Near Eastern Archaeology, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany, 3 Anthropologie-BuÈro Jungklaus, Berlin, Germany a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract Prone burials are among the most distinctive deviant burials during the Middle Ages and early modern period. Despite their worldwide distribution, the meaning of this burial practice is still a matter of debate. So far, a comprehensive analysis of prone burials is lacking for OPEN ACCESS Central Europe. By compiling evidence from Germany, Switzerland and Austria, this study Citation: Alterauge A, Meier T, Jungklaus B, Milella investigates how these findings fit into the scope of medieval funerary practices. 95 prone M, LoÈsch S (2020) Between belief and fear - burials from 60 archaeological sites were analyzed regarding geographical distribution, dat- Reinterpreting prone burials during the Middle ing, burial features, body position, age-at-death and sex. We applied descriptive statistics Ages and early modern period in German- speaking Europe. PLoS ONE 15(8): e0238439. accompanied by multiple correspondence analysis in order to highlight possible multivariate https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238439 patterns in the dataset. Prone burials occur in funerary and non-funerary contexts, with a Editor: Peter F. Biehl, University at Buffalo - The predominance of single churchyard burials, followed by favored and exterior location and State University of New York, UNITED STATES settlements. -

Paper Title – Template <Arial, 14Pt, Bold>

16th International Conference on “Cultural Heritage and New Technologies” Vienna, 2011 WORKSHOP Georeferencing Historical Maps 9 16th International Conference on “Cultural Heritage and New Technologies” Vienna, 2011 10 16th International Conference on “Cultural Heritage and New Technologies” Vienna, 2011 More or less 90° Georeferencing Peter Nenning’s plan of the Benedictine Abbey of Petershausen, Konstanz, South West Germany David BIBBY Landesamt für Denkmalpflege Baden-Württemberg im Regierungspräsidium Stuttgart, Germany Abstract: In 2002 in Petershausen quarter of Konstanz South West Germany planning permission was granted for a large new communal administrative building within the area once occupied by ancillary buildings of the Benedictine Abbey in Petershausen. An excavation was planned and in preparation, historical plan material was examined. Exceptional in this respect is the plan of Petershausen by the Austrian architect Peter Nenning dating to around 1800. The plan shows a collection of buildings varying in date from medieval to the late Baroque. The question arose as to whether the plan might be a useful and accurate historical source? Could it help us as a non-intrusive prospection tool in the forefront of the excavation and provide us preemptively with important details allowing a more targeted Excavation? The project turned into a discourse between the ordered world view of a late Baroque/Rococo architect and today’s real, considerably less rectangular topography. And with the dig that followed it was possible to test the method as a soft prospection method against the actual excavation results. Keywords: historical plans, rectification, excavation, Konstanz. Petershausen Abbey The Petershausen quarter of Konstanz lies to the north, across the Rhine from the ancient town. -

Prologue Felix Mater Constantia

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-41731-0 — The Trauma of Monastic Reform Alison I. Beach Excerpt More Information 1 Prologue Felix Mater Constantia On October 28, 992, Bishop Gebhard II (979– 995) stood on the shore of the Seerhein, the four- kilometer stretch of the river Rhine that connects the upper section of Lake Constance to the lower as it l ows past the city of Constance. The bishop could easily see the towers of the cathedral and the city’s four smaller churches positioned, “like pearls in a necklace,” along the old Roman road that ran through the heart of the city as he stood waiting to be ferried across the river in one of the square- ended, l at- bottomed boats of the sort used for centuries to navigate the lake.1 He may even have been able to hear the the din of Constance’s bustling market, where the city’s merchants, many specializing in locally produced linen, haggled with traders from far to the north and east. This expand- ing market, attested as early as 900, was already outgrowing its original site along the southwest wall of the cathedral precinct. 2 The Niederburg , 1 Helmut Maurer, Konstanz im Mittelalter , vol. 1, Geschichte der Stadt Konstanz (Constance: Stadler Verlag, 1989), 79; see also Lutz Fenske, Die Deutschen Königspfalzen. Beiträge zu ihrer historischen und archäologischen Erforschung , vol. 3 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1963– ), 265, which states that the ferry that linked Petershausen and Constance was the most important in the city; on the history of passenger travel and commercial shipping on Lake Constance from late antiquity to the Industrial Revolution, see Alfons Zettler, “Heilige, Mönche und Laien Unterwegs. -

Evidence on the Political Principal-Agent Problem Fromvoting on Public Finance for Concert Halls

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Potrafke, Niklas Working Paper Evidence on the political principal-agent problem fromvoting on public finance for concert halls ifo Working Paper, No. 164 Provided in Cooperation with: Ifo Institute – Leibniz Institute for Economic Research at the University of Munich Suggested Citation: Potrafke, Niklas (2013) : Evidence on the political principal-agent problem fromvoting on public finance for concert halls, ifo Working Paper, No. 164, ifo Institute - Leibniz Institute for Economic Research at the University of Munich, Munich This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/84185 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Ifo Institute – Leibniz Institute for Economic Research at the University of Munich Evidence on the political principal-agent problem from voting on public finance for concert halls Niklas Potrafke Ifo Working Paper No. -

A Walking Tour

A Walking Tour EN A WARM WELCOME TO CONSTANCE... ... the beating heart of the Lake Constance four-country region. With its historical centre, the Council of Constance and its fine, small museums, Constance has a uniquely tangible history, a vibrant present and a wealth of ideas and plans for the future. Art, culture, pleasure and water characterise the largest city on Lake Constance – the perfect place to walk, cycle, shop or just linger a while. Exciting cultural tours guide locals and visitors alike from significant locations in the his- tory of Constance to modern locations on the banks of Lake Constance and the Rhine. Simply immerse yourself in the city, take an inspiring journey through the centuries on this unique tour and soak up the abundant sensory impulses. KEY Council sites Barrier-free access 3 A WALKING GUIDE 1 TOURIST INFORMATION OFFICE Starting point for the walking tour. You can also get all sorts of useful information about Constance here. 2 FORMER HOSPITAL OF THE HOLY SPIRIT AND HOTEL ZUR KRONE In 1225, as an expression of their growing independence, the people of Constance founded a municipal hospital (Bürgerspital Zum Heiligen Geist), which consisted of several buildings. It served as a hospital until 1812 and 4 | HOTEL “ZUM GOLDENEN ADLER” is today a modern residential and business complex. In the post office’s main counter hall there are medieval frescoes from the original building which are well worth seeing. The former Hotel Zur Krone and the former hos- pital building next door are now part of the Tertianum retirement home.