In This Special Issue, We Hope You Will Join Us in Honoring Those Ancestors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Now Available for Free As A

JARED CULTURAL STUDIES / AFRICANA STUDIES $14.95 | £11 In the proud tradition of Fanon, Cabral, Malcolm X, and Steve Biko, BALL Jared Ball speaks in the voice of the decolonial Other, ofering a much- needed mind transplant to anyone preferring to ignore the liberatory potential inhering in the hip-hop phenomenon of mixtape.—Ward Churchill / Author of A Little Matter of Genocide With this book, Jared Ball correctly and cogently posits hip-hop in its I rightful place—as the most important literary form to emerge from the MIX 20th century.—Boots Riley / Te Coup Te value of a committed, revolutionary Ph.D. with an ear for the WHAT truth and skills on the mic and turntable? Priceless.—Glen Ford / Executive Editor of BlackAgendaReport.com I In a moment of increasing corporate control in the music indus- LIKE try, where three major labels call the shots on which artists are heard and seen, Jared Ball analyzes the colonization and control ! of popular music and posits the homemade hip-hop mixtape as an emancipatory tool for community resistance. I Mix What I Like! is a revolutionary investigation of the cultural dimension of anti- JARED racist organizing in the Black community. A MIXTAPE BALL Blending together elements from internal colonialism theory, cul- tural studies, political science, and his own experience on the mic, Jared positions the so-called “hip-hop nation” as an extension of the internal colony that is modern African America, and suggests that the low-tech hip-hop mixtape may be one of the best weapons MANIFESTO we have against Empire. -

The Dragons Fire

1 The Dragons Fire “When the prison doors are opened, the real dragon will fly out” Ho Chi Minh THE NATIONAL JERICHO MOVEMENT NEWSLETTER in Fierce Determination Since 1996 August 15-Sept 15, 2020, Vol. 30 http://www.thejerichomovement.com P.O. Box 2164 Chesterfield, Virginia 23832 Steering Committee Advisory Board 1. Chair: Jihad Abdulmumit 1. Paulette Dauteuil 2. Secretary: Adam Carpinelli 2. Anne Lamb 3. Treasurer: Ashanti Alston 3. Frank Velgara 4. Fund Raising Chairperson: A’isha Mohammad 4. Kazi Toure 5. Dragon Fire Newsletter Editor: A’isha Mohammad 5. Jorge Chang 6. Tekla Johnson Revolutionary Greetings, Welcome to our National Jericho Movement Newsletter. Thank you to all of our members and affiliates who contribute critical information regarding our Political Prisoners/Prisoners of War as well as updates on activities, events and actions. Moving forward, we stand in fierce determination and solidarity to free our remaining Political Prisoners and Prisoners of War still languishing behind the dungeon walls. Much work has been done by Jericho and other organizations, and there is still much more work to do. With 20 years behind us and much work ahead, Jericho is growing and is taking on new projects and missions. Our shared vision is that we will reach a time in this country (and others) wherein there will be no more Political Prisoners/Prisoners of War. We envision the day when they all will walk free and into their family’s arms-who have been waiting for decades. We hope you join us in making this a reality. “Do what must be done, discover your humanity and your love in revolution." Fallen Black Panther Field Marshal, Comrade George L. -

Still Black Still Strong

STIll BLACK,STIll SfRONG l STILL BLACK, STILL STRONG SURVIVORS Of THE U.S. WAR AGAINST BLACK REVOlUTIONARIES DHORUBA BIN WAHAD MUMIA ABU-JAMAL ASSATA SHAKUR Ediled by lim f1elcher, Tonoquillones, & Sylverelolringer SbIII01EXT(E) Sentiotext(e) Offices: P.O. Box 629, South Pasadena, CA 91031 Copyright ©1993 Semiotext(e) and individual contributors. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 978-0-936756-74-5 1098765 ~_.......-.;,;,,~---------:.;- Contents DHORUDA BIN W"AHAD WARWITIllN 9 TOWARD RE'rHINKING SEIl'-DEFENSE 57 THE CuTnNG EDGE OF PRISONTECHNOLOGY 77 ON RACISM. RAp AND REBElliON 103 MUM<A ABU-JAMAL !NrERVIEW FROM DEATH Row 117 THE PRIsON-HOUSE OF NATIONS 151 COURT TRANSCRIPT 169 THE MAN MALCOLM 187 P ANIllER DAZE REMEMBERED 193 ASSATA SHAKUR PRISONER IN THE UNITED STATES 205 CHRONOLOGY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 221 FROM THE FBI PANTHER FILES 243 NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS 272 THE CAMPAIGN TO FREE BLACK POLITICALPRISONERS 272 Contents DHORUBA BIN "W AHAD WAKWITIllN 9 TOWARD REnnNKINO SELF-DEFENSE 57 THE CurnNG EOOE OF PRISON TECHNOLOGY 77 ON RACISM, RAp AND REBEWON 103 MUMIA ABU-JAMAL !NrERVIEW FROM DEATH Row 117 THE PRIsoN-HOUSE OF NATIONS 151 COURT TRANSCRIPT 169 THE MAN MALCOLM 187 PANTHER DAZE REMEMBERED 193 ASSATA SHAKUR PJusONER IN THE UNITED STATES 205 CHRONOLOGY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 221 FROM THE FBI PANTHER FILES 243 NOTES ON CONTRmUTORS 272 THE CAMPAIGN TO FREE BUCK POLITICAL PRISONERS 272 • ... Ahmad Abdur·Rahmon (reIeo,ed) Mumio Abu·lomol (deoth row) lundiolo Acoli Alberlo '/lick" Africa (releosed) Ohoruba Bin Wahad Carlos Perez Africa Chorl.. lim' Africa Can,uella Dotson Africa Debbi lim' Africo Delberl Orr Africa Edward Goodman Africa lonet Halloway Africa lanine Phillip. -

The Republicrats: a Plague on Both Th

The Black Commentator - The Republicrats: A Plague on Both Their Ho... http://www.blackcommentator.com/276/276_kir_republicrats_plague_bo... May 8, 2008 - Issue 276 Home The Republicrats: A Plague on Both Their Houses Keeping it Real By Larry Pinkney BlackCommentator.com Editorial Board The acquittal last month of the New York City police murderers of Sean Bell was in actuality also the acquittal by the judicial, legislative, corporate, and military apparatus of Amerikkka for every single past and present atrocity committed against Black, Brown, Red and Yellow peoples in this nation and throughout the world. It represents the very essence of how truly rotten to the core the Democratic and Republican parties [i.e. the Republicrats] really are. This is not merely about New York City, and the impunity with which the system of the U.S. Empire functions to commit brutal, wanton murder. No, this continues to be about the physical and systemic hundreds of thousands of lynchings in Amerikkka, and the despicable and brutal murders of Emmet Till, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr., little Bobby Hutton, Fred Hampton & Mark Clark, and so very many other women and men in this nation. This is about the U.S. genocide against the Indigenous peoples - our Red brothers and sisters - and the avaricious thievery of their lands. This is about “America” as it really and truly is. This is about the systemic terrorism of capitalism against the poor - all of us - Black, Brown, Red, and yes, White. This is about the Republicrats and their treachery, betrayal, bloody lies and hypocrisy - all of them. -

Empowering a New Generation

| 1 Tuesday, January 29, 2019 Empowering a New Generation From Black Panther and convict to writer, poet, producer, college professor, Academy Award nominee, and youth advocate, Jamal Joseph’s life has taken a circuitous path to the present. His is a story of perennial social activism, advancing lessons from his Black Panther days to empower a new generation. Excuse Me, Young Brother, I Just Did In the late 1960s, Eddie Joseph was a high school honor student, slated to graduate early and begin college. That path took a detour. A long one. Impassioned to resolve the social, economic, and political wrongs he saw in his Bronx community and the nation, 15-year-old Eddie was drawn to the ideology of the Black Panther Party, which was just gaining a national presence. He remembers riding the subway to the Panther office in Harlem with two friends to offer his services, enraged by the recent assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. He was ready to fight, even kill if necessary, to serve the cause. At the Panther office, a leader called the earnest teen up front. As Joseph stood by his side, the leader pulled open a desk drawer and reached far into it. Joseph’s heart pounded. He was prepared to be handed a gun—the power for social change. Instead, he was handed a stack of books, such as The Autobiography of Malcolm X and The Wretched of the Earth, Frantz Fanon’s 1961 work on the cultural foundations of social movements. Taken aback, Joseph said, “Excuse me, brother, I thought you were going to arm me.” The Panther’s reply: “Excuse me, young brother, I just did.” By 16, Eddie—now called Jamal—learned that the militant group the FBI declared to be “the greatest threat to America” was a multifaceted entity. -

Ursula Mctaggart

RADICALISM IN AMERICA’S “INDUSTRIAL JUNGLE”: METAPHORS OF THE PRIMITIVE AND THE INDUSTRIAL IN ACTIVIST TEXTS Ursula McTaggart Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy In the Departments of English and American Studies Indiana University June 2008 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Doctoral Committee ________________________________ Purnima Bose, Co-Chairperson ________________________________ Margo Crawford, Co-Chairperson ________________________________ DeWitt Kilgore ________________________________ Robert Terrill June 18, 2008 ii © 2008 Ursula McTaggart ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A host of people have helped make this dissertation possible. My primary thanks go to Purnima Bose and Margo Crawford, who directed the project, offering constant support and invaluable advice. They have been mentors as well as friends throughout this process. Margo’s enthusiasm and brilliant ideas have buoyed my excitement and confidence about the project, while Purnima’s detailed, pragmatic advice has kept it historically grounded, well documented, and on time! Readers De Witt Kilgore and Robert Terrill also provided insight and commentary that have helped shape the final product. In addition, Purnima Bose’s dissertation group of fellow graduate students Anne Delgado, Chia-Li Kao, Laila Amine, and Karen Dillon has stimulated and refined my thinking along the way. Anne, Chia-Li, Laila, and Karen have devoted their own valuable time to reading drafts and making comments even in the midst of their own dissertation work. This dissertation has also been dependent on the activist work of the Black Panther Party, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, the International Socialists, the Socialist Workers Party, and the diverse field of contemporary anarchists. -

New Orleans: Searching for Weapons of Mass Destruction

San Francisco Bay View - National Black Newspaper of the Year About us 4/5/06 What’s Going On Calendar Search sfbayview.com Searching for Search WWW Opportunities weapons of mass Advertise in the Bay View! Pen pals destruction: Where is the Bayview Page One Stories San Francisco Bay View Wanda’s TiPapa Lucian, age blight? National Black Newspaper picks 11: ‘Now I live in Part 1 4917 Third Street the streets’ by Carol Harvey San Francisco California 94124 Spiritual News by TiPapa Lucian as Phone: (415) 671-0789 told to Lyn Duff Fax: (415) 671-0316 Afrikan Anti-Terrorism Email: [email protected] Shame, shame on From warrior to PG&E! writer: Chernoh M. Come to the power Bah’s journey plant Tuesday, April by Mumia Abu-Jamal 11, at noon How many hits did the Bay View website get in by Marie Harrison A nation of December 2005? colonists – and race 1,885,651! College students laws Don’t miss out. Hit us up today! Education join social justice by Juan Santos www.sfbayview.com - new choice: movement by CC Campbell-Rock Bay View Web Exclusives Neutralize and Supporters Why is NY Times attacking destroy: The surround Rep. Venezuelan aid to the poor? University of continuing vendetta Cynthia McKinney by Olivia Goumbri Phoenix against the after incident with Panthers Capitol Police A series by Larry Pinkney and by David Stokes, Atlanta Gerald Sanders Inquirer Stop the DeVry University execution of Rep. Maxine Waters West Contra Costa Hasan Shakur spurs Congress to School District may Dedication fund as well as grant diplomas to by Hasan Shakur, Minister of voice support for all who earn them Human Rights of the New Haiti ITT Tech Thousands complete high school Afrikan Black Panther Party – by Lyn Duff but are denied diploma due to exit Prison Chapter. -

You've Gone Past Us Now

the blue afterwards Felix Shafer November 25, 2010 2 You've gone past us now. beloved comrade: north american revolutionary and political prisoner My sister and friend of these 40 years, it's over Marilyn Buck gone through the wire out into the last whirlwind. With time's increasing distance from her moment of death on the afternoon of August 3, 2010, at home in Brooklyn New York, the more that I have felt impelled to write a cohesive essay about Marilyn, the less possible such a project has become. She died at 62 years of age, surrounded by people who loved and still love her truly. She died just twenty days after being released from Carswell federal prison in Texas. Marilyn lived nearly 30 years behind bars. It was the determined effort of Soffiyah Elijah, her attorney and close friend of more than a quarter century that got her out of that prison system at all. Her loss leaves a wound that insists she must be more than a memory and still so much more than a name circulating in the bluest afterwards. If writing is one way of holding on to Marilyn, it also ramifies a crazed loneliness. Shadows lie down in unsayable places. I'm a minor player in the story who wants to be scribbling side by side with her in a cafe or perched together overlooking the Hudson from a side road along the Palisades. This work of mourning is fragmentary, impossible, subjective, politically unofficial, lovingly biased, flush with anxieties over (mis)representation, hopefully evocative of some of the 'multitude' of Marilyns contained within her soul, strange and curiously punctuated by shifts into reverie and poetic time. -

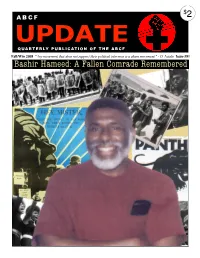

Bashir Hameed

$ A B C F 2 U P D A T E Q UA R T E R LY P U B L I C AT I O N O F T H E A B C F F a l l / Win 2008 "Any movement that does not support their political internees is a sham movement." - O. Lutalo Issue #51 Bashir Hameed: A Fallen Comrade Remembered In the 80s, however, the ABC began to gain What is the Anarchist Black Cross Federation? popularity again in the US and Europe. For years, the A B C ’s name was kept alive by a The Anarchist Black Cross (ABC) began provide support to those who were suff e r i n g number of completely autonomous groups shortly after the 1905 Russian Revolution. It because of their political beliefs. scattered throughout the globe and support- formed after breaking from the Political Red In 1919, the org a n i z a t i o n ’s name changed ing a wide variety of prison issues. Cross, due to the group’s refusal to support to the Anarchist Black Cross to avoid confu- In May of 1995, a small group of A B C Anarchist and Social Revolutionary Political sion with the International Red Cross. collectives merged into a federation whose Prisoners. The new group, naming itself the Through the 1920s and until 1958, the org a n- aim was to focus on the overall support and Anarchist Red Cross (ARC), began to pro- ization worked under various other names defense of Political Prisoners and Prisoners vide aid to those Political Prisoners who but provided the same level of support as the of Wa r. -

From Mass Education to Mass Incarceration." a History of Education for the Many: from Colonization and Slavery to the Decline of US Imperialism

Malott, Curry. "From Mass Education to Mass Incarceration." A History of Education for the Many: From Colonization and Slavery to the Decline of US Imperialism. London,: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021. 165–174. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 27 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350085749.ch-10>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 27 September 2021, 09:00 UTC. Copyright © Curry Malott 2021. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 10 From Mass Education to Mass Incarceration Introduction: Connection to the Previous Chapter In Chapter 9 we saw the systemic crisis of realization and the mobilization of teachers and activists in response. In the present chapter we explore the expansion of education in the post-Second World War era as capitalism’s labor needs shifted with the continued development of labor-saving technologies, which coincided with the emergence of a new era in mass mobilizations spearheaded by the African American Civil Rights movement and its leaders. New crises of realization develop as the labor-saving technologies eventually render large segments of the US working-class redundant. Unlike previous manifestations of racism designed to either justify the super- exploitation of slavery or maintain a form of the plantation system through prisoner-leasing schemes after Reconstruction, the particular form of “super- predator” anti-Blackness of the post-Second World War mass incarceration era was a response to Black workers especially being expelled from production as a by-product of automation (Puryear 2012). -

PETITION List 04-30-13 Columns

PETITION TO FREE LYNNE STEWART: SAVE HER LIFE – RELEASE HER NOW! • 1 Signatories as of 04/30/13 Arian A., Brooklyn, New York Ilana Abramovitch, Brooklyn, New York Clare A., Redondo Beach, California Alexis Abrams, Los Angeles, California K. A., Mexico Danielle Abrams, Ann Arbor, Michigan Kassim S. A., Malaysia Danielle Abrams, Brooklyn, New York N. A., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Geoffrey Abrams, New York, New York Tristan A., Fort Mill, South Carolina Nicholas Abramson, Shady, New York Cory a'Ghobhainn, Los Angeles, California Elizabeth Abrantes, Cambridge, Canada Tajwar Aamir, Lawrenceville, New Jersey Alberto P. Abreus, Cliffside Park, New Jersey Rashid Abass, Malabar, Port Elizabeth, South Salma Abu Ayyash, Boston, Massachusetts Africa Cheryle Abul-Husn, Crown Point, Indiana Jamshed Abbas, Vancouver, Canada Fadia Abulhajj, Minneapolis, Minnesota Mansoor Abbas, Southington, Connecticut Janne Abullarade, Seattle, Washington Andrew Abbey, Pleasanton, California Maher Abunamous, North Bergen, New Jersey Andrea Abbott, Oceanport, New Jersey Meredith Aby, Minneapolis, Minnesota Laura Abbott, Woodstock, New York Alexander Ace, New York, New York Asad Abdallah, Houston, Texas Leela Acharya, Toronto, Canada Samiha Abdeldjebar, Corsham, United Kingdom Dennis Acker, Los Angeles, California Mohammad Abdelhadi, North Bergen, New Jersey Judith Ackerman, New York, New York Abdifatah Abdi, Minneapolis, Minnesota Marilyn Ackerman, Brooklyn, New York Hamdiya Fatimah Abdul-Aleem, Charlotte, North Eddie Acosta, Silver Spring, Maryland Carolina Maria Acosta, -

Arm the Spirit

August-December 1992 No. 14/15 The Spirit Price: $2.00 Autonomist/Anti-Imperialist Journal For A Free And Independent Kurdistan! y , 33: 1ft : r lll||||il||ll|l|lli|i l^ i iliiliiiiiiB The Spirit from our e-mail address. We're Still Here! We wish to end ihis "editorial" with a correction and a call for solidarity. First off, in our last issue we After an absence of many months we're finally reprinted a "Revolutionary Cells (RZ)" communique back with a new issue. As always, the usual problems from a group that claimed to carry out an action against seem to plague us, with money being our biggest neme- fascists. We have learned that this action was not success- sis. Our last issue came out August 1992, and since then ful and was not carried out by the RZ's. Comrades in we have slowly been putting together this issue. As one Europe have informed us that the bombs that had been month turned into another, we realized that a lot of the placed did not detonate and if this had occured, people information and articles in this issue were becoming may have been injured or killed. This is not the practice dated. This was particularly problematic in light of the of the RZ's. If people could be injured or killed as the ;|ip;}it:;|s;|$^ fact that we are a bi-monthly publication and we attempt result of an armed action by them, they will not cany it to be up-to-date in our coverage of various revolutionary out.