From Downtown to the Inner Harbor: Baltimore's Sustainable Revitalization Part 1: the Charles Center Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

All Hazards Plan for Baltimore City

All-Hazards Plan for Baltimore City: A Master Plan to Mitigate Natural Hazards Prepared for the City of Baltimore by the City of Baltimore Department of Planning Adopted by the Baltimore City Planning Commission April 20, 2006 v.3 Otis Rolley, III Mayor Martin Director O’Malley Table of Contents Chapter One: Introduction .........................................................................................................1 Plan Contents....................................................................................................................1 About the City of Baltimore ...............................................................................................3 Chapter Two: Natural Hazards in Baltimore City .....................................................................5 Flood Hazard Profile .........................................................................................................7 Hurricane Hazard Profile.................................................................................................11 Severe Thunderstorm Hazard Profile..............................................................................14 Winter Storm Hazard Profile ...........................................................................................17 Extreme Heat Hazard Profile ..........................................................................................19 Drought Hazard Profile....................................................................................................20 Earthquake and Land Movement -

Port Services Guide for Visiting Ships to Baltimore

PORT SERVICES GUIDE Port Services Guide For Visiting Ships to Baltimore Created by Sail Baltimore Page 1 of 17 PORT SERVICES GUIDE IMPORTANT PHONE NUMBERS IN BALTIMORE POLICE, FIRE & MEDICAL EMERGENCIES 911 Police, Fire & Medical Non-Emergencies 311 Baltimore City Police Information 410-396-2525 Inner Harbor Police (non-emergency) 410-396-2149 Southeast District - Fells Point (non-emergency) 410-396-2422 Sgt. Kenneth Williams Marine Police 410-396-2325/2326 Jeffrey Taylor, [email protected] 410-421-3575 Scuba dive team (for security purposes) 443-938-3122 Sgt. Kurt Roepke 410-365-4366 Baltimore City Dockmaster – Bijan Davis 410-396-3174 (Inner Harbor & Fells Point) VHF Ch. 68 US Navy Operational Support Center - Fort McHenry 410-752-4561 Commander John B. Downes 410-779-6880 (ofc) 443-253-5092 (cell) Ship Liaison Alana Pomilia 410-779-6877 (ofc) US Coast Guard Sector Baltimore - Port Captain 410-576-2564 Captain Lonnie Harrison - Sector Commander Commander Bright – Vessel Movement 410-576-2619 Search & Rescue Emergency 1-800-418-7314 General Information 410-789-1600 Maryland Port Administration, Terminal Operations 410-633-1077 Maryland Natural Resources Police 410-260-8888 Customs & Border Protection 410-962-2329 410-962-8138 Immigration 410-962-8158 Sail Baltimore 410-522-7300 Laura Stevenson, Executive Director 443-721-0595 (cell) Michael McGeady, President 410-942-2752 (cell) Nan Nawrocki, Vice President 410-458-7489 (cell) Carolyn Brownley, Event Assistant 410-842-7319 (cell) Page 2 of 17 PORT SERVICES GUIDE PHONE -

Saudi Students Association at University of Baltimore SSAUB

Saudi Students Association at UB “SSAUB” Saudi Students Guide at University of Baltimore Saudi students association at University of Baltimore SSAUB New Saudi Students Guide at the University of Baltimore Hello new Saudi students in the city of Baltimore and the State of Maryland. We wish you a nice life and achieve your academic goals. This form contains information you may find useful during your stay here, especially new students in the University of Baltimore. The information presented below is some of the nearby places to the University of Baltimore and have been arranged from closest. The information includes Apartments, Shopping Malls, International Markets, Mosques, Supermarkets (Super Stores), Supermarkets (Jomlah), Transportations, Daycare, Hospitals, police, and some Mobile Applications you may need. You also may need to contact the Saudi students Association at the University of Baltimore for any more information. 1 Saudi Students Association at UB “SSAUB” Saudi Students Guide at University of Baltimore Housing The Fitzgerald at UB Midtown Address: 1201 W Mt Royal Ave, Baltimore, MD 21217 Phone:(443) 426-2524 http://www.fitzgeraldbaltimore.com/?ctd_ac=1081055&ctx_name=LocalOnlineDirectories&ctx_Ad%252 0Source=LocalOnlineDirectories&utm_source=googleplaces&utm_medium=listing&utm_campaign=loca ldirectories The Mount Royal Apartments Address: 103 E Mt Royal Ave, Baltimore, MD 21202 Phone:(888) 692-5413 http://www.themtroyal.com The Varsity at UB Address: 30 W Biddle St, Baltimore, MD 21201 Phone: (410) 637-3730 http://varsityatub.com/ -

COVID-19 FOOD INSECURITY RESPONSE GROCERY and PRODUCE BOX DISTRIBUTION SUMMARY April – June, 2020 Prepared by the Baltimore Food Policy Initiative

COVID-19 FOOD INSECURITY RESPONSE GROCERY AND PRODUCE BOX DISTRIBUTION SUMMARY April – June, 2020 Prepared by the Baltimore Food Policy Initiative OVERVIEW In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Baltimore Food Policy Initiative developed an Emergency Food Strategy. An Emergency Food Planning team, comprised of City agencies and critical nonprofit partners, convened to guide the City’s food insecurity response. The strategy includes distributing meals, distributing food, increasing federal nutrition benefits, supporting community partners, and building local food system resilience. Since COVID-19 reached Baltimore, public-private partnerships have been mobilized; State funding has been leveraged; over 3.5 million meals have been provided to Baltimore youth, families, and older adults; and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Online Purchasing Pilot has launched. This document provides a summary of distribution of food boxes (grocery and produce boxes) from April to June, 2020, and reviews the next steps of the food distribution response. GOAL STATEMENT In response to COVID-19 and its impact on health, economic, and environmental disparities, the Baltimore Food Policy Initiative has grounded its short- and long-term strategies in the following goals: • Minimizing food insecurity due to job loss, decreased food access, and transportation gaps during the pandemic. • Creating a flexible grocery distribution system that can adapt to fluctuating numbers of cases, rates of infection, and specific demographics impacted by COVID-19 cases. • Building an equitable and resilient infrastructure to address the long-term consequences of the pandemic and its impact on food security and food justice. RISING FOOD INSECURITY DUE TO COVID-19 • FOOD INSECURITY: It is estimated that one in four city residents are experiencing food insecurity as a consequence of COVID-191. -

Download This

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) r~ _ B-1382 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Completelhe National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property I historic name Highfield House____________________________________________ other names B-1382___________________________________________________ 2. Location street & number 4000 North Charles Street ____________________ LJ not for publication city or town Baltimore___________________________________________________ D vicinity state Maryland code MD county Baltimore City code 510 zip code 21218 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ^ nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property E] meets D does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant D nationally D statewide ^ locally. -

Kimmel in the C M Nity

THE SIDNEY KIMMEL COMPREHENSIVE CANCER CENTE R AT JOHNS HOPKINS KIMMEL IN THE C MNITY PILLARS OF PROGRESS Closing the Gap in Cancer Disparities MUCH PROGRESS HAS been made in Maryland toward eliminating cancer disparities, and I am very proud of the role the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center has played in this progress. Overcoming cultural and institutional barriers and increasing minority participation in clinical trials is a priority at the Kimmel Cancer Center. Programs like our Center to Reduce Cancer Disparities, Office of Community Cancer Research, the Maryland Cigarette Restitution Fund at Johns Hopkins, and Day at the Market are helping us obtain this goal. Historical Trends (1975-2012) The challenge before Maryland is greater than Mortality, Maryland most states. Thirty percent of Maryland’s citizens are All Cancer Sites, Both Sexes, All Ages Deaths per 100,000 resident population African-American, compared to a national average 350 of 13 percent. We view our state’s demographics as 300 black (includes hispanics) an opportunity to advance the understanding of 250 factors that cause disparities, unravel the science White (includes hispanics) 200 that may also play a contributory role, and become the model for the rest of the country. Our experts are 150 setting the standards for removing barriers and 100 hispanic (any race) improving cancer care for African-Americans and 50 other minorities in Maryland and around the world. 0 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 Although disparities still exist in Maryland, we year of Death continue to close that gap. Overall cancer death rates have declined in our state, and we have narrowed the gap in cancer death disparities between African -American and white Marylanders by more than 60 percent since 2001, far exceeding national progress. -

Inner Harbor West

URBAN RENEWAL PLAN INNER HARBOR WEST DISCLAIMER: The following document has been prepared in an electronic format which permits direct printing of the document on 8.5 by 11 inch dimension paper. If the reader intends to rely upon provisions of this Urban Renewal Plan for any lawful purpose, please refer to the ordinances, amending ordinances and minor amendments relevant to this Urban Renewal Plan. While reasonable effort will be made by the City of Baltimore Development Corporation to maintain current status of this document, the reader is advised to be aware that there may be an interval of time between the adoption of any amendment to this document, including amendment(s) to any of the exhibits or appendix contained in the document, and the incorporation of such amendment(s) in the document. By printing or otherwise copying this document, the reader hereby agrees to recognize this disclaimer. INNER HARBOR WEST URBAN RENEWAL PLAN DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT BALTIMORE, MARYLAND ORIGINALLY APPROVED BY THE MAYOR AND CITY COUNCIL OF BALTIMORE BY ORDINANCE NO. 1007 MARCH 15, 1971 AMENDMENTS ADDED ON THIS PAGE FOR CLARITY NOVEMBER, 2004 I. Amendment No. 1 approved by the Mayor and City Council of Baltimore by Ordinance 289, dated April 2, 1973. II. Amendment No. 2 approved by the Mayor and City Council of Baltimore by Ordinance No. 356, dated June 27, 1977. III. (Minor) Amendment No. 3 approved by the Board of Estimates on June 7, 1978. IV. Amendment No. 4 approved by the Mayor and City Council of Baltimore by Ordinance No. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

B-4480 NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking V in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word process, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name One Charles Center other names B-4480 2. Location street & number 100 North Charles Street Q not for publication city or town Baltimore • vicinity state Maryland code MP County Independent city code 510 zip code 21201 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this G3 nomination • request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property C3 meets • does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant D nationally • statewide K locally. -

WINDSOR HILLS HISTORIC DISTRICT Other Name/Site Number B-1352

NPSForm 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name WINDSOR HILLS HISTORIC DISTRICT other name/site number B-1352 2. Location street & number Roughly bounded by Clifton Avenue, Talbot Road, Prospect Circle, Lawina Road, Westchester Road, Woodhaven Ave.f Chelsea Terrace, Gwynns Falls Parkway, and Windsor Mill Road. • not for publication city or town Baltimore • vicinity state Maryland code MP county Independent City code 005 zip code 21216 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this H nomination • request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property E3 meets • does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Creating Opportunity in GREATER BALTIMORE's Next Economy

Building from Strength Creating opportunity in greater Baltimore’s next economy Jennifer S. Vey fellow The Brookings i nsTiTuTion | Metropolitan p olicy p rograM | 2012 acknowledgments the Brookings institution Metropolitan policy program would like to thank the annie e. casey foundation for their generous support of this report. the author is particularly grateful to patrice cromwell (Director of economic Development and integration initiatives, center for community and economic opportunity), whose knowledge of and passion for the issues discussed in these pages have been critical to the project. the Metro program also thanks the rockefeller foundation, John D. and catherine t. Macarthur foundation, Heinz endowments, ford foundation, george gund foundation, f.B. Heron foundation, and the Metropolitan leadership council for their ongoing support of the program. the author also wishes to express her thanks and gratitude to the many people who provided important information, guidance, and advice that helped build and improve the report. first, she wants to thank all those who provided personal or small group interviews, or otherwise provided feedback on the project, including (in alphabetical order): tim armbruster (goldseker foundation); Bill Barnes (university of Maryland, Manufacturing assistance program); Diane Bell-Mckoy (associated Black charities); avonette Blanding (Maritime applied physics corporation); paul Brophy (Brophy and reilly, llc); Bill Burwell, Martin Herbst, paul Matino, Janee pierre-louis, and Jeanne townsend (u.S. export assistance center); richard clinch (university of Baltimore Jacob france institute); Martha connolly (Maryland industrial partnerships program); neil Davis (emerging technology centers); Dennis faber (tiMe center at the community college of Baltimore county); Stuart fitzgibbon (Domino Sugar); kirby fowler (Downtown partnership of Baltimore); andy frank (Johns Hopkins university); Mike galiazzo (the regional Manufacturing institute of Maryland); Susan ganz (lion Brothers inc.); Bob giloth (annie e. -

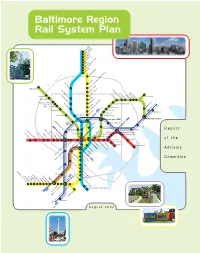

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report of the Advisory Committee August 2002 Advisory Committee Imagine the possibilities. In September 2001, Maryland Department of Transportation Secretary John D. Porcari appointed 23 a system of fast, convenient and elected, civic, business, transit and community leaders from throughout the Baltimore region to reliable rail lines running throughout serve on The Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Advisory Committee. He asked them to recommend the region, connecting all of life's a Regional Rail System long-term plan and to identify priority projects to begin the Plan's implemen- important activities. tation. This report summarizes the Advisory Committee's work. Imagine being able to go just about everywhere you really need to go…on the train. 21 colleges, 18 hospitals, Co-Chairs 16 museums, 13 malls, 8 theatres, 8 parks, 2 stadiums, and one fabulous Inner Harbor. You name it, you can get there. Fast. Just imagine the possibilities of Red, Mr. John A. Agro, Jr. Ms. Anne S. Perkins Green, Blue, Yellow, Purple, and Orange – six lines, 109 Senior Vice President Former Member We can get there. Together. miles, 122 stations. One great transit system. EarthTech, Inc. Maryland House of Delegates Building a system of rail lines for the Baltimore region will be a challenge; no doubt about it. But look at Members Atlanta, Boston, and just down the parkway in Washington, D.C. They did it. So can we. Mr. Mark Behm The Honorable Mr. Joseph H. Necker, Jr., P.E. Vice President for Finance & Dean L. Johnson Vice President and Director of It won't happen overnight. -

Final Final Kromer

______________________________________________________________________________ CENTER ON URBAN AND METROPOLITAN POLICY THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION VACANT-PROPERTY POLICY AND PRACTICE: BALTIMORE AND PHILADELPHIA John Kromer Fels Institute of Government University of Pennsylvania A Discussion Paper Prepared for The Brookings Institution Center on Urban and Metropolitan Policy and CEOs for Cities October 2002 ______________________________________________________________________ THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION CENTER ON URBAN AND METROPOLITAN POLICY SUMMARY OF RECENT PUBLICATIONS * DISCUSSION PAPERS/RESEARCH BRIEFS 2002 Calling 211: Enhancing the Washington Region’s Safety Net After 9/11 Holding the Line: Urban Containment in the United States Beyond Merger: A Competitive Vision for the Regional City of Louisville The Importance of Place in Welfare Reform: Common Challenges for Central Cities and Remote Rural Areas Banking on Technology: Expanding Financial Markets and Economic Opportunity Transportation Oriented Development: Moving from Rhetoric to Reality Signs of Life: The Growth of the Biotechnology Centers in the U.S. Transitional Jobs: A Next Step in Welfare to Work Policy Valuing America’s First Suburbs: A Policy Agenda for Older Suburbs in the Midwest Open Space Protection: Conservation Meets Growth Management Housing Strategies to Strengthen Welfare Policy and Support Working Families Creating a Scorecard for the CRA Service Test: Strengthening Banking Services Under the Community Reinvestment Act The Link Between Growth Management and Housing