Connection, Collaboration, and Division in Early ‘70S Indian Country

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Carolina State Youth Council Handbook

NORTH CAROLINA STATE YOUTH COUNCIL Organizing and Advising State Youth Councils Handbook MAY 2021 Winston Salem Youth Council TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction...........................................................................................2 a. NC Council for Women & Youth Involvement.........................2 b. History of NC Youth Councils.....................................................3 c. Overview of NC State Youth Council Program.......................4 2. Organizing a Youth Council...............................................................6 a. Why Start a Youth Council...........................................................6 b. Structure of a Youth Council.......................................................7 c. How to Get Started........................................................................9 3. Advising a Youth Council...................................................................11 a. Role of a Youth Council Advisor...............................................11 b. Leadership Conferences.............................................................11 c. Guidelines for Hosting a Leadership Conference...............12 d. Event Protocol........................................................................21 4. North Carolina State Youth Council Program.................25 a. State Youth Council Bylaws.............................................25 b. Chartered Youth Councils.....................................................32 c. Un-Chartered Youth Councils.................................................34 -

C:\94PAP2\PAP APPA Txed01 Psn: Txed01 Appendix a / Administration of William J

Appendix AÐDigest of Other White House Announcements The following list includes the President's public sched- Indian and Alaska Native Culture and Arts Develop- ule and other items of general interest announced by ment Board of Trustees. the Office of the Press Secretary and not included The President announced his intention to appoint elsewhere in this book. Kit Dobelle as a member of the White House Com- mission on Presidential Scholars. August 1 In the morning, the President traveled to Jersey August 4 City, NJ, where he met with families from the State The President announced his intention to nominate to discuss their problems with the health care system. Herschelle Challenor to the National Security Edu- In the late afternoon, he returned to Washington, cation Board. DC. The President announced his intention to nominate Sheldon C. (Shay) Bilchik as Administrator of the Of- August 2 fice of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention In the evening, the President and Hillary Clinton at the Department of Justice. attended a Democratic National Committee fundraiser at a private residence in Oxon Hill, MD. August 5 The President declared major disasters in Oregon In the afternoon, the President and Hillary and and Washington following severe damage to the ocean Ä Chelsea Clinton went to Camp David, MD. salmon fishing industries caused by the El Nino The President announced his intention to nominate weather pattern and recent drought. Kenneth Spencer Yalowitz as Ambassador to Belarus. The White House announced that the President The President announced his intention to appoint has invited President Leonid Kuchma of Ukraine to Joseph M. -

Women's History Is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating in Communities

Women’s History is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating In Communities A How-To Community Handbook Prepared by The President’s Commission on the Celebration of Women in American History “Just think of the ideas, the inventions, the social movements that have so dramatically altered our society. Now, many of those movements and ideas we can trace to our own founding, our founding documents: the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. And we can then follow those ideas as they move toward Seneca Falls, where 150 years ago, women struggled to articulate what their rights should be. From women’s struggle to gain the right to vote to gaining the access that we needed in the halls of academia, to pursuing the jobs and business opportunities we were qualified for, to competing on the field of sports, we have seen many breathtaking changes. Whether we know the names of the women who have done these acts because they stand in history, or we see them in the television or the newspaper coverage, we know that for everyone whose name we know there are countless women who are engaged every day in the ordinary, but remarkable, acts of citizenship.” —- Hillary Rodham Clinton, March 15, 1999 Women’s History is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating In Communities A How-To Community Handbook prepared by the President’s Commission on the Celebration of Women in American History Commission Co-Chairs: Ann Lewis and Beth Newburger Commission Members: Dr. Johnnetta B. Cole, J. Michael Cook, Dr. Barbara Goldsmith, LaDonna Harris, Gloria Johnson, Dr. Elaine Kim, Dr. -

Harvesting Summary EU Youth Conference 02 – 05 October 2020 Imprint

Harvesting Summary EU Youth Conference 02 – 05 October 2020 Imprint Imprint This brochure is made available free of charge and is not intended for sale. Published by: German Federal Youth Council (Deutscher Bundesjugendring) Mühlendamm 3 DE-10178 Berlin www.dbjr.de [email protected] Edited by: German Federal Youth Council (Deutscher Bundesjugendring) Designed by: Friends – Menschen, Marken, Medien | www.friends.ag Credits: Visuals: Anja Riese | anjariese.com, 2020 (pages 4, 9, 10, 13, 16, 17, 18, 20, 23, 26, 31, 34, 35, 36, 40, 42, 44, 50, 82–88) picture credits: Aaron Remus, DBJR: title graphic, pages 4 // Sharon Maple, DBJR: page 6 // Michael Scholl, DBJR: pages 12, 19, 21, 24, 30, 37, 39, graphic on the back // Jens Ahner, BMFSFJ: pages 7, 14, 41,43 Element of Youth Goals logo: Mireille van Bremen Using an adaption of the Youth Goals logo for the visual identity of the EU Youth Conference in Germany has been exceptionally permitted by its originator. Please note that when using the European Youth Goals logo and icons you must follow the guidelines described in detail in the Youth Goals Design Manual (http://www.youthconf.at/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/BJV_Youth-Goals_ DesignManual.pdf). Berlin, December 2020 Funded by: EU Youth Conference – Harvesting Summary 1 Content Content Preamble 3 Context and Conference Format 6 EU Youth Dialogue 7 Outcomes of the EU Youth Conference 8 Programme and Methodological Process of the Conference 10 Harvest of the Conference 14 Day 1 14 Day 2 19 World Café 21 Workshops and Open Sessions 23 Day 3 24 Method: -

Friends of the Capitol 2009-June 2010 Report

Friends of the Capitol 2009-June 2010 Report Our Mission Statement: Friends of the Capitol is a tax-exempt 501(c)(3) corporation that is devoted to maintaining and improving the beauty and grandeur of the Oklahoma State Capitol building and showcasing the magnificent gifts of art housed inside. This mission is accomplished through a partnership with private citizens wishing to leave their footprint in our state's rich history. Education and Development In 2009 and 2010 Friends of the Capitol (FOC) participated in several educational and developmental projects informing fellow Oklahomans of the beauty of the capitol and how they can participate in the continuing renovations of Oklahoma State Capitol building. In March of 2010, FOC representatives made a trip to Elk City and met with several organizations within the community and illustrated all the new renovations funded by Friends of the Capitol supporters. Additionally in 2009 FOC participated in the State Superintendent’s encyclo-media conference and in February 2010 FOC participated in the Oklahoma City Public Schools’ Professional Development Day. We had the opportunity to meet with teachers from several different communities in Oklahoma, and we were pleased to inform them about all the new restorations and how their school’s name can be engraved on a 15”x30”paver, and placed below the Capitol’s south steps in the Centennial Memorial Plaza to be admired by many generations of Oklahomans. Gratefully Acknowledging the Friends of the Capitol Board of Directors Board Members Ex-Officio Paul B. Meyer, Col. John Richard Chairman USA (Ret.) MA+ Architecture Oklahoma Department Oklahoma City of Central Services Pat Foster, Vice Chairman Suzanne Tate Jim Thorpe Association Inc. -

A Reserved Right Does Not Make a Wrong

Tulsa Law Review Volume 48 Issue 2 Winter 2012 A Reserved Right Does Not Make a Wrong Wyatt M. Cox Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Wyatt M. Cox, A Reserved Right Does Not Make a Wrong, 48 Tulsa L. Rev. 373 (2013). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr/vol48/iss2/20 This Casenote/Comment is brought to you for free and open access by TU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tulsa Law Review by an authorized editor of TU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cox: A Reserved Right Does Not Make a Wrong A RESERVED RIGHT DOES NOT MAKE A WRONG 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................. 374 II. TREATIES WITH THE TRIBAL NATIONS ............................................. 375 A. The Canons of Construction. ........................... ...... 375 B. The Power and Purpose of the Indian Treaty ............................... 376 C. The Equal Footing Doctrine .............................................377 D. A Brief Overview of the Policy History of Treaties ............ ........... 378 E. The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek.........................380 III. THE ESTABLISHMENT AND EXPANSION OF THE INDIAN RESERVED WATER RIGHT ....381 A. Winters v. United States: The Establishment of Reserved Indian Water Rights...................................................382 B. Arizona v. California:Not Only Enough Water to Fulfill the Purposes of Today, but Enough to Fulfill the Purposes of Forever ...................... 383 C. Cappaertv. United States: The Supreme Court Further Expands the Winters Doctrine ........................................ 384 IV. Two OKLAHOMA CASES THAT SUPPORT THE TRIBAL NATION CLAIMS .................... 385 A. Choctaw Nation v. Oklahoma (The Arkansas River Bank Case) .................. -

World Program of Action for Youth (Wpay)

WORLD PROGRAM OF ACTION FOR YOUTH (WPAY) “Full and Effective Participation of youth in the life of society and in decision-making” ITALY TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Action 1 5 Action 2 6 Action 3 7 Action 4 8 Action 5 9 Action 6 10 Conclusion 11 Sources 12 2 INTRODUCTION The revision of WPAY poses new questions and challenges for the analysis of the Italian situation during the period 1995-2005. The most interesting area to be evaluated is the one concerning national youth policies, youth empowerment and participation. This report aims at highlighting the national situation during this period, and above all, wants to discuss the measures implemented and what is still needed. The WPAY provides different areas to be discussed within its framework, including youth employment, globalization and intergenerational dialogue. For what concerns area 10 (Full and Effective Participation of Youth in the life of Society and in Decision-making), it presents six different points governments agreed to work on back in 1995. These are as follows: • Action 1 Governments agreed to “Improving access to information in order to enable young people to make better use of their opportunities to participate in decision-making” • Action 2 Governments agreed to “Developing and/or strengthening opportunities for young people to learn their rights and responsibilities” • Action 3 Governments agreed to “Encouraging and promoting youth associations through financial, educational and technical support and promotion of their activities” • Action 4 Governments agreed -

![Presidential Files; Folder: 7/7/77 [1]; Container 29](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5508/presidential-files-folder-7-7-77-1-container-29-405508.webp)

Presidential Files; Folder: 7/7/77 [1]; Container 29

7/7/77 [1] Folder Citation: Collection: Office of Staff Secretary; Series: Presidential Files; Folder: 7/7/77 [1]; Container 29 To See Complete Finding Aid: http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/library/findingaids/Staff%20Secretary.pdf THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON z 0 H 8 H u >t ,:( ~ MONDALE COSTANZA [,C. EIZENSTAT JORDAN LIPSHUTZ MOORE POWELL WATSON FOR STAFFING FOR INFORMATION 1\C FROM PRESIDENT'S OUTBOX LOG IN/TO PRESIDENT TODAY IMMEDIATE TURNAROUND ARAGON BOURNE BRZEZINSKI HOYT HUTCHESON JAGODA KING THE PRESIDENT'S SCHEDULE Thursday- July 7, 1977 8:15 Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski The Oval Office. 9:00 Meeting to Discuss EOP Reorganization {60 min.) · Report. {Mr. James Mcintyre) • The Cabinet Room. 10:30 Mr. Jody Powell The OVal Office. 11:00 Meeting with Mr. Albert Shanker, President; (15 min.) Mr. Robert Porter, Secretary-Treasurer, and _, the .Executive Committee 1 American Federation of Teachers 1 AFL-CIO - The Cabinet Room. · 11:30 Vice President Walter F. Mondale, Admiral Stansfield Turner, and Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski - OVal Office. 12:30 Lunch with Mrs. Rosalynn Carter ~ · Oval Office • • 1:30 Meeting with Mr. Marshall Sh~lman. (15 min.) (Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski) - Oval Office. 2:45 Meeting with Ambassador Leonard Woodcock, {15 min.) Secretary Cyrus Vance, Assistant Secretary Richard Holbrooke, and Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski. The Cabinet Room. THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON July 7, 1977 Stu Eizenstat ~-:- ....... Charlie Schultze The attached was returned in the President's outbox. It is forwarded to you for your information. Rick Hutcheson Re: The U.S. Trade Balance t z 0 H 8 H u ~ < rz.. -- ; V'GQ MONDALE COSTANZA EIZENSTAT JORDAN LIPSHUTZ MOORE POWELL WATSON FOR STAFFING FOR INFORMATION - FROM PRESIDENT'S OUTBOX I"' LOG IN/TO PRESIDENT TODAY IMMEDIATE TURNAROUND ARAGON BOURNE ··-BRZEZINSKI HOYT HUTCHESON JAGODA KING :::: HE :='RESID.UE' HAS SEEN. -

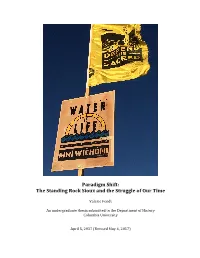

Paradigm Shift: the Standing Rock Sioux and the Struggle of Our Time

Paradigm Shift: The Standing Rock Sioux and the Struggle of Our Time Valerie Fendt An undergraduate thesis submitted to the Department of History Columbia University April 5, 2017 (Revised May 4, 2017) Table of Contents Page 3 Acknowledgements Page 4 Introduction Page 9 Chapter One: The Shifting Dispositions of Settler Colonialism Page 26 Chapter Two: From Resistance to Resurgence Page 42 Chapter Three: The Standing Rock Sioux and the Struggle of Our Time Page 57 Conclusion Page 59 Notes Page 72 Bibliography 2 Acknowledgements As a student who has had the great fortune to study at Columbia University I would like to recognize, honor, and thank the Lenni-Lenape people upon whose land this university sits and I have had the freedom to roam. I am indebted to the Indigenous scholars and activists who have shared their knowledge and made my scholarship on this subject what it is. All limitations are strictly my own, but for what I do know I am indebted to them. I am grateful to all of the wonderful people I met at Standing Rock in October of 2016. I can best describe the experience as a gift I will carry with me always. Thank you to the good people of the “solo chick warrior camp,” to Vanessa for inviting us in, to Leo for giving me the chance to employ usefulwhiteallyship, to Alexa for the picture that adorns this cover. I would like to thank the history professors who have given so generously of their time, who have invested their energy and their work to assist my academic journey, encouraged my curiosity, helped me recognize my own voice, and believed it deserved to be heard. -

The American Indian Movement, the Trail of Broken Treaties, and the Politics of Media

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History History, Department of 7-2009 Framing Red Power: The American Indian Movement, the Trail of Broken Treaties, and the Politics of Media Jason A. Heppler Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss Part of the History Commons Heppler, Jason A., "Framing Red Power: The American Indian Movement, the Trail of Broken Treaties, and the Politics of Media" (2009). Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History. 21. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss/21 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. FRAMING RED POWER: THE AMERICAN INDIAN MOVEMENT, THE TRAIL OF BROKEN TREATIES, AND THE POLITICS OF MEDIA By Jason A. Heppler A Thesis Presented to the Faculty The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: History Under the Supervision of Professor John R. Wunder Lincoln, Nebraska July 2009 2 FRAMING RED POWER: THE AMERICAN INDIAN MOVEMENT, THE TRAIL OF BROKEN TREATIES, AND THE POLITICS OF MEDIA Jason A. Heppler, M.A. University of Nebraska, 2009 Adviser: John R. Wunder This study explores the relationship between the American Indian Movement (AIM), national newspaper and television media, and the Trail of Broken Treaties caravan in November 1972 and the way media framed, or interpreted, AIM's motivations and objectives. -

Congressional Papers Roundtable NEWSLETTER Society of American Archivists Fall/Winter 2016

Congressional Papers Roundtable NEWSLETTER Society of American Archivists Fall/Winter 2016 A Historic Election By Ray Smock The election of Donald Trump as the 45th pres- Dear CPR Members, ident of the United States is one of historic This year marked the 30-year proportions that we will anniversary of the first official be studying and analyz- meeting of the Congressional Students, faculty, and community members attend the ing for years to come, as Papers Roundtable, and it seems Teach-in on the 2016 Election at the Byrd Center. On stage, left to right: Dr. Aart Holtslag, Dr. Stephanie Slo- we do with all our presi- a fitting time to reflect on this cum-Schaffer, Dr. Jay Wyatt, and Dr. Max Guirguis. (Not pictured: Dr. Joseph Robbins) dential and congression- group’s past achievements and al elections. Here at the the important work happening Byrd Center our mission has not changed, nor would it change no now. matter which political party controls Congress or the Executive Branch. The CPR held its first official meeting in 1986 and since then We are a non-partisan educational organization on the campus of has contributed numerous talks Shepherd University. Our mission is to advance representative de- and articles, outreach and advo- mocracy by promoting a better understanding of the United States cacy work, and publications, Congress and the Constitution through programs that reach and en- such as The Documentation of Con- gage citizens. This is an enduring mission that is not dependent on gress and Managing Congressional the ebbs and flows of party politics. -

VITA Gary D. Wekkin 11 Tucker Creek

VITA Gary D. Wekkin 11 Tucker Creek Road Conway AR 72034 501.327.8259 (H) / 501.450.5686 (O) Personal History Born 6 June 1949 Married, Two Sons Academic History Ph. D., Political Science, University of British Columbia, 1980 M. A., Political Science, University of British Columbia, 1972 B. A., Asian Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1971 (including 23 hours of Chinese; 6 hours of French) Graduate Summary Specialization: American Politics (Parties, Interest Groups, Political Behavior, State Politics & Presidency) Dissertation: “The Wisconsin Open Primary and the Democratic National Committee.” (David J. Elkins, supervisor; Richard G. C. Johnston and Donald E. Blake, committee members; William J. Crotty, external examiner.) Overall Graduate Average: 122.2 (First Class, British System) Graduate Fellowship Holder, 1972-75 Dr. Norman MacKenzie American Alumni Award, 1971-72 Positions Held 1982-present University of Central Arkansas – Professor (with tenure), 1992-____; Assistant Professor, 1982-86; Associate Professor, 1986-92. 1981-1982 University of Missouri-Kansas City – Visiting Assistant Professor 1978-1981 University of Wisconsin Center-Janesville – Lecturer 1978 Ada Deer for Secretary of State (WI) – Acting Campaign Director 1975-1976 Democratic Party of Wisconsin (Madison WI) – Field Officer & Delegate Selection/Affirmative Action Coordinator 1973-1974 Institute of International Relations, University of British Columbia (Vancouver) – Graduate Assistant to Director Courses Taught American Presidency Politics of Presidential Selection Interest Groups & Money in Politics Political Parties & Electoral Problems Political Behavior Campaign Organization & Management State & Local Government Public Opinion (not since 1982) Scope & Methods (not since 1988) Legislative Process (not since 1981) International Politics (not since 1981) Awards & Honors University of Arkansas William J.