The Flute Music of Paul Desenne: a Comparative Analytical Study of Representative Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African Diaspora and Colombian Popular Music in the Twentieth Century1

African Diaspora and Colombian Popular Music in the Twentieth Century1 Peter Wade In this paper I argue that the concept of disapora is problematic insofar as it implies a process of traffic outwards from an origin point (usually seen as geographical, cultural and/or “racial”). This origin is often seen as being a key to the definition of diaspora—without it, the concept descends into generalized incoherence (Brubaker 2005). I want to argue for the continued usefulness of a concept of diaspora, in which the “origin” is understood as a space of imagination (which is not to say that it is imaginary, although it may also be that) and in which the connections between the “outlying” points of the diaspora are as important, or more so, than the connections between the outliers and the origin. Analytically speaking, diaspora has to be distanced from simple concerns with uni-directional outward dispersals from a single origin point (which may also carry certain masculinist connotations). Specifically, I think the concept of diaspora points at a kind of cultural continuity but one where “cultural continuity appears as the mode of cultural change” (Sahlins 1993, 19). For theorists such as Hall and Gilroy, diaspora serves as an antidote to what Gilroy calls “camp thinking” and its associated essentialism: diasporic identities are “creolized, syncretized, hybridized and chronically impure 1. This paper was first given in abbreviated form as part of the Center for Black Music Research’s Conference on Black Music Research, Chicago, February 14–17, 2008, in the ses- sion “Black Diaspora Musical Formations: Identification, History, and Historiography.” I am grateful to the CBMR for the invitation to participate in the conference. -

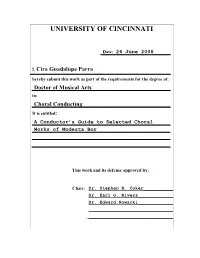

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 26 June 2006 I, Cira Guadalupe Parra hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in: Choral Conducting It is entitled: A Conductor’s Guide to Selected Choral Works of Modesta Bor This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Dr. Stephen R. Coker___________ Dr. Earl G. Rivers_____________ Dr. Edward Nowacki_____________ _______________________________ _______________________________ A Conductor’s Guide to Selected Choral Works of Modesta Bor A document submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati In a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Ensembles and Conducting Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2006 by Cira Parra 620 Clinton Springs Ave Cincinnati, Ohio 45229 [email protected] B.M., University of Cincinnati, College-Conservatory of Music, 1987 M.M., University of Cincinnati, College-Conservatory of Music, 1989 Committee Chair: Stephen R. Coker ABSTRACT Modesta Bor (1926-98) was one of the outstanding Venezuelan composers, conductors, music educators and musicologists of the twentieth century. She wrote music for orchestra, chamber music, piano solo, piano and voice, and incidental music. She also wrote more than 95 choral works for mixed voices and 130 for equal-voice choir. Her style is a mixture of Venezuelan nationalism and folklore with European traits she learned in her studies in Russia. Chapter One contains a historical background of the evolution of Venezuelan art music since the colonial period, beginning in 1770. Knowing the state of art music in Venezuela helps one to understand the unusual nature of the Venezuelan choral movement that developed in the first half of the twentieth century. -

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

WORKSHOP: Around the World in 30 Instruments Educator’S Guide [email protected]

WORKSHOP: Around The World In 30 Instruments Educator’s Guide www.4shillingsshort.com [email protected] AROUND THE WORLD IN 30 INSTRUMENTS A MULTI-CULTURAL EDUCATIONAL CONCERT for ALL AGES Four Shillings Short are the husband-wife duo of Aodh Og O’Tuama, from Cork, Ireland and Christy Martin, from San Diego, California. We have been touring in the United States and Ireland since 1997. We are multi-instrumentalists and vocalists who play a variety of musical styles on over 30 instruments from around the World. Around the World in 30 Instruments is a multi-cultural educational concert presenting Traditional music from Ireland, Scotland, England, Medieval & Renaissance Europe, the Americas and India on a variety of musical instruments including hammered & mountain dulcimer, mandolin, mandola, bouzouki, Medieval and Renaissance woodwinds, recorders, tinwhistles, banjo, North Indian Sitar, Medieval Psaltery, the Andean Charango, Irish Bodhran, African Doumbek, Spoons and vocals. Our program lasts 1 to 2 hours and is tailored to fit the audience and specific music educational curriculum where appropriate. We have performed for libraries, schools & museums all around the country and have presented in individual classrooms, full school assemblies, auditoriums and community rooms as well as smaller more intimate settings. During the program we introduce each instrument, talk about its history, introduce musical concepts and follow with a demonstration in the form of a song or an instrumental piece. Our main objective is to create an opportunity to expand people’s understanding of music through direct expe- rience of traditional folk and world music. ABOUT THE MUSICIANS: Aodh Og O’Tuama grew up in a family of poets, musicians and writers. -

Pan-March-2020.Pdf

PANJOURNAL OF THE BRITISH FLUTE SOCIETY MARCH 2020 “This is my Flute. There are many like it, but this one is mine” Juliette Hurel Maesta 18K - Forte Headjoint pearlflutes.eu Principal Flautist of the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra contents The British Flute Society news & events 24 President 2 BFS NEWS William Bennett OBE 4 NOTES FROM THE CHAIR 6 NEWS Vice President 11 FLUTE CHOIR NEWS Wissam Boustany 13 TRADE NEWS 14 EVENTS LISTINGS Honorary Patrons 16 INTERNATIONAL EVENTS Sir James Galway 23 FLUTE CHOIR FOCUS: and Lady Jeanne Galway WOKING FLUTE CHOIR 32 Conductorless democracy in action. Vice Presidents Emeritus Atarah Ben-Tovim MBE features Sheena Gordon 24 ALEXANDER MURRAY: I’VE GONE ON LEARNING THE FLUTE ALL MY LIFE Secretary Cressida Godfrey examines an astonishing Rachel Shirley career seven decades long and counting. [email protected] 32 CASE FOR MOVEMENT EDUCATION Musicians move for a living. Kelly Mollnow 39 Membership Secretary Wilson shows them how to do it freely and [email protected] efficiently through Body Mapping. 39 WILLIAM BENNETT’S The British Flute Society is a HAPPY FLUTE FESTIVAL Charitable Incorporated Organisation Edward Blakeman describes some of the registered charity number 1178279 enticing treats on offer this summer in Wibb’s feel-good festival. Pan 40 GRADED EXAMS AND BEYOND: The Journal of the EXPLORING THE OPTIONS AVAILABLE 40 British Flute Society The range of exams can be daunting for Volume 39 Number 1 student and teacher alike. David Barton March 2020 gives a comprehensive review. 42 STEPHEN WESSEL: Editor A NATIONAL TREASURE Carla Rees Judith Hall gives a personal appreciation of [email protected] the flutemaker in the year of his retirement. -

Colombian Nationalism: Four Musical Perspectives for Violin and Piano

COLOMBIAN NATIONALISM: FOUR MUSICAL PERSPECTIVES FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO by Ana Maria Trujillo A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Music The University of Memphis December 2011 ABSTRACT Trujillo, Ana Maria. DMA. The University of Memphis. December/2011. Colombian Nationalism: Four Musical Perspectives for Violin and Piano. Dr. Kenneth Kreitner, Ph.D. This paper explores the Colombian nationalistic musical movement, which was born as a search for identity that various composers undertook in order to discover the roots of Colombian musical folklore. These roots, while distinct, have all played a significant part in the formation of the culture that gave birth to a unified national identity. It is this identity that acts as a recurring motif throughout the works of the four composers mentioned in this study, each representing a different stage of the nationalistic movement according to their respective generations, backgrounds, and ideological postures. The idea of universalism and the integration of a national identity into the sphere of the Western musical tradition is a dilemma that has caused internal struggle and strife among generations of musicians and artists in general. This paper strives to open a new path in the research of nationalistic music for violin and piano through the analyses of four works written for this type of chamber ensemble: the third movement of the Sonata Op. 7 No.1 for Violin and Piano by Guillermo Uribe Holguín; Lopeziana, piece for Violin and Piano by Adolfo Mejía; Sonata for Violin and Piano No.3 by Luís Antonio Escobar; and Dúo rapsódico con aires de currulao for Violin and Piano by Andrés Posada. -

A Musical Instrument of Global Sounding Saadat Abdullayeva Doctor of Arts, Professor

Focusing on Azerbaijan A musical instrument of global sounding Saadat ABDULLAYEVA Doctor of Arts, Professor THE TAR IS PRObabLY THE MOST POPULAR MUSICAL INSTRUMENT AMONG “The trio”, 2005, Zakir Ahmadov, AZERbaIJANIS. ITS SHAPE, WHICH IS DIFFERENT FROM OTHER STRINGED INSTRU- bronze, 40x25x15 cm MENTS, IMMEDIATELY ATTRACTS ATTENTION. The juicy and colorful sounds to the lineup of mughams, and of a coming from the strings of the tar bass string that is used only for per- please the ear and captivate people. forming them. The wide range, lively It is certainly explained by the perfec- sounds, melodiousness, special reg- tion of the construction, specifically isters, the possibility of performing the presence of twisted steel and polyphonic chords, virtuoso passag- copper strings that convey all nuanc- es, lengthy dynamic sound rises and es of popular tunes and especially, attenuations, colorful decorations mughams. This is graphically proved and gradations of shades all allow by the presence on the instrument’s the tar to be used as a solo, accom- neck of five frets that correspondent panying, ensemble and orchestra 46 www.irs-az.com instrument. But nonetheless, the tar sounding board instead of a leather is a recognized instrument of solo sounding board contradict this con- mughams when the performer’s clusion. The double body and the mastery and the technical capa- leather sounding board are typical of bilities of the instrument manifest the geychek which, unlike the tar, has themselves in full. The tar conveys a short neck and a head folded back- the feelings, mood and dreams of a wards. Moreover, a bow is used play person especially vividly and fully dis- this instrument. -

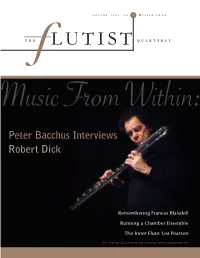

The Flutist Quarterly Volume Xxxv, N O

VOLUME XXXV , NO . 2 W INTER 2010 THE LUTI ST QUARTERLY Music From Within: Peter Bacchus Interviews Robert Dick Remembering Frances Blaisdell Running a Chamber Ensemble The Inner Flute: Lea Pearson THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL FLUTE ASSOCIATION , INC :ME:G>:C8: I=: 7DA9 C:L =:69?D>CI ;GDB E:6GA 6 8ji 6WdkZ i]Z GZhi### I]Z cZl 8Vadg ^h EZVgaÉh bdhi gZhedch^kZ VcY ÓZm^WaZ ]ZVY_d^ci ZkZg XgZViZY# Djg XgV[ihbZc ^c ?VeVc ]VkZ YZh^\cZY V eZg[ZXi WaZcY d[ edlZg[ja idcZ! Z[[dgiaZhh Vgi^XjaVi^dc VcY ZmXZei^dcVa YncVb^X gVc\Z ^c dcZ ]ZVY_d^ci i]Vi ^h h^bean V _dn id eaVn# LZ ^ck^iZ ndj id ign EZVgaÉh cZl 8Vadg ]ZVY_d^ci VcY ZmeZg^ZcXZ V cZl aZkZa d[ jcbViX]ZY eZg[dgbVcXZ# EZVga 8dgedgVi^dc *). BZigdeaZm 9g^kZ CVh]k^aaZ! IC (,'&& -%%".),"(',* l l l # e Z V g a [ a j i Z h # X d b Table of CONTENTS THE FLUTIST QUARTERLY VOLUME XXXV, N O. 2 W INTER 2010 DEPARTMENTS 5 From the Chair 51 Notes from Around the World 7 From the Editor 53 From the Program Chair 10 High Notes 54 New Products 56 Reviews 14 Flute Shots 64 NFA Office, Coordinators, 39 The Inner Flute Committee Chairs 47 Across the Miles 66 Index of Advertisers 16 FEATURES 16 Music From Within: An Interview with Robert Dick by Peter Bacchus This year the composer/musician/teacher celebrates his 60th birthday. Here he discusses his training and the nature of pedagogy and improvisation with composer and flutist Peter Bacchus. -

Espressivo Program Notes April 2018 the Evolution of Chamber Music For

Espressivo Program Notes April 2018 The evolution of chamber music for a mixed ensemble of winds and strings coincides with the domestication of the double bass. Previously used as an orchestral instrument or in dance music, the instrument was admitted into the salon in the late eighteenth century. The granddaddy of the genre is Beethoven’s Septet of 1800, for four strings, clarinet, horn and bassoon. Beethoven seems to have discovered that the largest string instrument, essentially doubling the cello an octave lower and with the capability to play six notes below the lowest note on the bassoon, provided overtones that enhanced the vibrations of the higher instruments. In any case, the popularity of the Septet, which sustains to this day, caused the original players to have a similar work commissioned from Franz Schubert, who added a second violin for his Octet (1824). (Espressivo performed it last season.) It is possible, if not probable, that Schubert’s good friend Franz Lachner wrote his Nonet for the same group, adding a flute, but the origins, and even the date of the composition are in dispute. An indicator might be the highlighting of the virtuosic violin part, as it would have been played by Ignaz Schuppanzigh, who had premiered both the Septet and the Octet. All three works, Septet, Octet and Nonet, have slow introductions to the first and last uptempo movements, and all include a minuet. All seem intended to please rather than to challenge. Beethoven’s Septet was commissioned by a noble patron for the delectation of his guests, as was Schubert’s Octet. -

SHOEMAKER, ANN H., DMA the Pedagogy of Becoming

SHOEMAKER, ANN H., D.M.A. The Pedagogy of Becoming: Identity Formation through the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra’s OrchKids and Venezuela’s El Sistema. (2012) Directed by Drs. Michael Burns and Gavin Douglas. 153 pp. Rapid development of El Sistema-inspired music programs around the world has left many music educators seeking the tools to emulate El Sistema effectively. This paper offers information to these people by evaluating one successful program in the United States and how it reflects the intent and mission of El Sistema. Preliminary research on El Sistema draws from articles and from information provided by Mark Churchill, Dean Emeritus of New England Conservatory’s Department of Preparatory and Continuing Education and director of El Sistema USA. Travel to Baltimore, Maryland and to four cities in Venezuela allowed for observation and interviews with people from the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra’s OrchKids program and four núcleos in El Sistema, respectively. OrchKids and El Sistema aim to improve the lives of their students and their communities, but El Sistema takes action only through music while OrchKids has a broader spectrum of activities. OrchKids also uses a wider variety of musical genres than El Sistema does. Both programs impact their students by giving them a strong sense of personal identity and of belonging to community. The children learn responsibility to the communities around them such as their neighborhood and their orchestra, and also develop a sense of belonging to a larger international music community. THE PEDAGOGY OF BECOMING: IDENTITY FORMATION THROUGH THE BALTIMORE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA’S ORCHKIDS AND VENEZUELA’S EL SISTEMA by Ann H. -

2018 Available in Carbon Fibre

NFAc_Obsession_18_Ad_1.pdf 1 6/4/18 3:56 PM Brannen & LaFIn Come see how fast your obsession can begin. C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Booth 301 · brannenutes.com Brannen Brothers Flutemakers, Inc. HANDMADE CUSTOM 18K ROSE GOLD TRY ONE TODAY AT BOOTH #515 #WEAREVQPOWELL POWELLFLUTES.COM Wiseman Flute Cases Compact. Strong. Comfortable. Stylish. And Guaranteed for life. All Wiseman cases are hand- crafted in England from the Visit us at finest materials. booth 408 in All instrument combinations the exhibit hall, supplied – choose from a range of lining colours. Now also NFA 2018 available in Carbon Fibre. Orlando! 00 44 (0)20 8778 0752 [email protected] www.wisemanlondon.com MAKE YOUR MUSIC MATTER Longy has created one of the most outstanding flute departments in the country! Seize the opportunity to study with our world-class faculty including: Cobus du Toit, Antero Winds Clint Foreman, Boston Symphony Orchestra Vanessa Breault Mulvey, Body Mapping Expert Sergio Pallottelli, Flute Faculty at the Zodiac Music Festival Continue your journey towards a meaningful life in music at Longy.edu/apply TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the President ................................................................... 11 Officers, Directors, Staff, Convention Volunteers, and Competition Committees ................................................................ 14 From the Convention Program Chair ................................................. 21 2018 Lifetime Achievement and Distinguished Service Awards ........ 22 Previous Lifetime Achievement and Distinguished -

Rehearing Beethoven Festival Program, Complete, November-December 2020

CONCERTS FROM THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS 2020-2021 Friends of Music The Da Capo Fund in the Library of Congress The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress (RE)HEARING BEETHOVEN FESTIVAL November 20 - December 17, 2020 The Library of Congress Virtual Events We are grateful to the thoughtful FRIENDS OF MUSIC donors who have made the (Re)Hearing Beethoven festival possible. Our warm thanks go to Allan Reiter and to two anonymous benefactors for their generous gifts supporting this project. The DA CAPO FUND, established by an anonymous donor in 1978, supports concerts, lectures, publications, seminars and other activities which enrich scholarly research in music using items from the collections of the Music Division. The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress was created in 1992 by William Remsen Strickland, noted American conductor, for the promotion and advancement of American music through lectures, publications, commissions, concerts of chamber music, radio broadcasts, and recordings, Mr. Strickland taught at the Juilliard School of Music and served as music director of the Oratorio Society of New York, which he conducted at the inaugural concert to raise funds for saving Carnegie Hall. A friend of Mr. Strickland and a piano teacher, Ms. Hull studied at the Peabody Conservatory and was best known for her duets with Mary Howe. Interviews, Curator Talks, Lectures and More Resources Dig deeper into Beethoven's music by exploring our series of interviews, lectures, curator talks, finding guides and extra resources by visiting https://loc.gov/concerts/beethoven.html How to Watch Concerts from the Library of Congress Virtual Events 1) See each individual event page at loc.gov/concerts 2) Watch on the Library's YouTube channel: youtube.com/loc Some videos will only be accessible for a limited period of time.