Early Childhood Development in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan Q

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Municipal Sustainability Plan Highlights 2016

CITY OF Martensville Municipal Sustainability Plan Highlights 2016 www.martensville.ca 1 We are committed to sustainability so we can meet the needs of our citizens now and in the future. Our Vision Martensville is a community of families, friends, and neighbours where we work, play, and grow together in a safe, active, and healthy environment - Martensville is a great place to call home. CONTENTS 4 Introduction 5 Pillars of Sustainability 6 Current Environment 9 Sustainability Pillar: Governance 10 Sustainability Pillar: Culture 11 Sustainability Pillar: Social 12 Sustainability Pillar: Environment 13 Sustainability Pillar: Economy 14 Success Factors 15 Implementing the Plan 2 3 INTRODUCTION PILLARS OF SUSTAINABILITY Martensville City Council is committed to providing and passing on a strategic direction and policy Governance: for future Councils that will continue to build a sustainable community within the values and beliefs Good governance is the effective management of our community. It includes the development of expressed by the citizens of Martensville. policy and leadership to implement policy. Martensville is practicing good governance using a variety of tools including this Municipal Sustainability Plan, Growth Management Plans, resource planning The Municipal Sustainability Plan provides the foundation by which Administration brings forward (financial, human, capacity) and working with other municipalities to plan how our communities will proposals or projects that will achieve City Council’s long-term direction. This plan was developed in grow collectively as one region. 2014 and is being used to guide departmental plans and budgets, and to deliver the programs and services our City requires, particularly as the City grows. It also takes into account the availability of Culture: human and financial resources. -

The Environment

background The Environment Cities across Canada and internationally are developing greener ways of building and powering communities, housing and infrastructure. They are also growing their urban forests, protecting wetlands and improving the quality of water bodies. The history of Saskatoon is tied to the landscape through agriculture and natural resources. The South Saskatchewan River that flows through the city is a cherished space for both its natural functions and public open space. Saskatonians value their environment. However, the ecological footprint of Saskatoon is relatively large. Our choices of where we live, how we travel around the city and the way that we use energy at home all have an impact on the health of the environment. The vision for Saskatoon needs to consider many aspects of the natural environment, from energy and air quality to water and trees. Our ecological footprint Energy sources Cities consume significant quantities of resources and Over half of Saskatoon’s ecological footprint is due to have a major impact on the environment, well beyond their energy use. As Saskatoon is located in a northern climate, borders. One way of describing the impact of a city is to there is a need for heating in the winter. As well, most measure its ecological footprint. The footprint represents Saskatoon homes are heated by natural gas. Although the land area necessary to sustain current levels of natural gas burns cleaner than coal and oil it produces resource consumption and waste discharged by that CO2, a greenhouse gas, into the atmosphere, making it an population. A community consumes material, water, and unsustainable energy source and the supply of natural gas energy, processes them into usable forms, and generates is limited. -

Th E Cost of Saying “No” T O Opportunity : Lessons From

T HE C OST OF S AYING “NO ” TO O PPORTUNITY: L ESSONS FROM THE R EJECTION OF THE W ARMAN U RANIUM R EFINERY JUNE 2003 FINALIZED MAY 2004 Prepared by the Saskatoon and District Chamber of Commerce 345 3rd Avenue South Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7K 1M6 www.eboardoftrade.com Phone: (306) 244-2151 Fax: (306) 244-8366 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Blind River: The Cost of an Opportunity Lost 4 3. Discussions and Process for the 1980 Decision 8 4. Active Participation May Have Landed The Project 17 5. The Panel and Process 18 6. Health Applications of Nuclear Technology 22 7. Consequences of Rejecting Opportunity 25 8. Historical Impact of Uranium Conversion 27 9. Potential Impact of Uranium-Based Electrical Generation 30 10. Influences on the Mobility of Investment Capital 32 11. Conclusions 34 12. Recommendations 36 Appendix A – Proxy Return on Investment Appendix B – GDP Loss Calculation Appendix C – Personal Income Tax Calculation Appendix D – Posters from the Late 1970s (Hard copies available from Chamber only) Appendix E – Calculations Appendix F – “Positive Assessment of Warman Refinery” Newspaper Article (Hard copy available from Chamber only) Appendix G – Energy Accident Statistics Saskatoon and District Chamber of Commerce 1 Uranium Industry Development in Saskatchewan Introduction In July 1980, the people of Saskatchewan missed a significant opportunity when the decision was made to not proceed with the construction of the world's largest uranium refinery in Saskatchewan. The project, now called the Blind River Refinery, did in fact proceed and is located in Blind River, Ontario. On Wednesday January 9, 1980, the Saskatoon Board of Trade (subsequently renamed the Saskatoon and District Chamber of Commerce) officially endorsed the construction of a uranium refinery near Warman1.In view of the Government of Canada’s review panel decision to not support the construction of the facility, through the Federal Environmental Assessment Review Office, this paper was developed to evaluate the economic impact of that decision on Saskatchewan today. -

CANADIAN ROCKIES North America | Calgary, Banff, Lake Louise

CANADIAN ROCKIES North America | Calgary, Banff, Lake Louise Canadian Rockies NORTH AMERICA | Calgary, Banff, Lake Louise Season: 2021 Standard 7 DAYS 14 MEALS 17 SITES Roam the Rockies on this Canadian adventure where you’ll explore glacial cliffs, gleaming lakes and churning rapids as you journey deep into this breathtaking area, teeming with nature’s rugged beauty and majesty. CANADIAN ROCKIES North America | Calgary, Banff, Lake Louise Trip Overview 7 DAYS / 6 NIGHTS ACCOMMODATIONS 3 LOCATIONS Fairmont Palliser Calgary, Banff, Lake Louise Fairmont Banff Springs Fairmont Chateau Lake Louise AGES FLIGHT INFORMATION 14 MEALS Minimum Age: 4 Arrive: Calgary Airport (YYC) 6 Breakfasts, 4 Lunch, 4 Dinners Suggested Age: 8+ Return: Calgary Airport (YYC) Adult Exclusive: Ages 18+ CANADIAN ROCKIES North America | Calgary, Banff, Lake Louise DAY 1 CALGARY, ALBERTA Activities Highlights: Dinner Included Arrive in Calgary, Welcome Dinner at the Hotel Fairmont Palliser Arrive in Calgary Land at Calgary Airport (YYC) and be greeted by Adventures by Disney representatives who will help you with your luggage and direct you to your transportation to the hotel. Morning And/Or Afternoon On Your Own in Calgary Spend the morning and/or afternoon—depending on your arrival time—getting to know this cosmopolitan city that still holds on to its ropin’ and ridin’ cowboy roots. Your Adventure Guides will be happy to give recommendations for things to do and see in this gorgeous city in the province of Alberta. Check-In to Hotel Allow your Adventure Guides to check you in while you take time to explore this premiere hotel located in downtown Calgary. -

To: Premier Scott Moe Room 226, 2405 Legislative Drive Regina, SK

Saskatchewan Public Works Association P.O. Box 131 Saskatoon, SK S7K 3K4 Ph: (306) 232-9300 Email: [email protected] http://saskatchewan.cpwa.net/ PRESIDENT Dale Petrun Dec 29, 2020 City of Saskatoon PAST PRESIDENT To: Premier Scott Moe Andrew Stevenson ATAP Infrastructure Management Room 226, 2405 Legislative Drive Saskatoon Regina, SK, Canada, S4S 0B3 PRESIDENT – ELECT [email protected] Staci Dobrescu City of Moose Jaw CHAPTER ADMINISTRATOR The Saskatchewan Chapter of the Canadian Public Works Association is a volunteer Trina Miller group of people that work together to raise awareness of the vital work that public TREASURER works professionals do in every community in our province. Stewart Schafer City of North Battleford Today we are contacting you to strongly encourage that as you set the priority on how DIRECTORS: Dennis Hunt COVID-19 vaccines are disseminated, you are considering public works professionals. Town of Saltcoats These committed men and women in public works perform many of the critical Andrew Fahlman City of Melville responsibilities fundamental to public health such as operating and maintaining critical infrastructure services including transportation; solid waste and refuse disposal systems; George Jakeman ATS Traffic a clean and safe water supply; safe and clean public buildings, spaces and facilities; and Regina logistical efforts in setting up COVID-19 testing sites – as well as operating and Eric Quail City of Saskatoon maintaining public parks, forests and green space, which have become so important to Neeraj Sanoj Canadians in sustaining health, wellness and physical distancing. These jobs are not only City of Regina critical to the continuity of protecting the lives of all Canadians, but many are at a APWA COUNCIL OF heightened risk of contracting COVID-19 because they come into daily contact with the CHAPTERS REPRESENTATIVE public. -

Retail Investment Sale

RETAIL INVESTMENT SALE 800 CENTENNIAL DRIVE NORTH, MARTENSVILLE SK OVERVIEW PROPERTY PROFILE As Saskatchewan’s newest and BUILDING SIZE LAND DETAILS fastest-growing city, Martensville 18,675 SF 44 parking stalls is demanding new industrial/retail for existing building LAND SIZE services. 800 Centennial Drive is 1.47 acres BUILDING DETAILS ideally located and is about 10 km • Built in 2016 outside of Saskatoon. Sitting on SALE PRICE • 5 total units 1.47acres of land, this 18,675 SF $3,570,000 • Currently fully-leased building is fully-leased by Phobia TAXES (2020) Auto Care, Alpyne Apparel, and LEGAL DESCRIPTION $10,701.03 Bravo Dance. Built in 2016, this Surface Parcel 203133484 high-quality development is very NOI ZONING well-maintained and it is a perfect $257,878.64 (2021) M - Industrial District fit for anyone looking for a current and future investment opportunity. TRUST US TO PUT YOU ON THE MAP ICRCOMMERCIAL.COM 800 CENTENNIAL DRIVE NORTH SITE PLAN TRUST US TO PUT YOU ON THE MAP ICRCOMMERCIAL.COM 244' 800 CENTENNIAL DRIVE NORTH THE MARTENSVILLE ADVANTAGE MARTENSVILLE METRICS There are so many reasons to invest in Martensville! TOTAL POPULATION (2018) 10,963 It is the fastest growing municipality in Saskatchewan MEDIAN AGE 31 and the second fastest growing municipality, over # OF OCCUPIED DWELLINGS 3,684 5,000, in Canada. The community sits along Highway 12 AVG HOUSEHOLD INCOME $125,877 in one of Saskatchewan’s most prosperous economic AVG HOUSEHOLD SIZE 3 regions, 10 minutes north of Saskatoon. AVG DAILY TRAFFIC (HWY 12) 13,700 Recent commercial growth has made Martensville a service centre to the area along this busy corridor. -

The Municipalities of Corman Park, Saskatoon, Martensville, Warman, and Osler Have Worked Together to Create a Draft Regional Plan

WELCOME TO THE PUBLIC INFORMATION SESSION JUNE 27, 2017 Open House 4–6:30 PM Public Presentation 6:30–7 PM Moderated Q&A 7–8 PM The municipalities of Corman Park, Saskatoon, Martensville, Warman, and Osler have worked together to create a draft Regional Plan. The new P4G Regional Plan will guide future growth by establishing a coordinated approach to land use, development, and infrastructure, and includes Strategies for regional governance and servicing coordination. We encourage you to review this information and submit your questions about the Plan. Please fill out the provided postcards and we will answer these questions during the Moderated Q&A. The draft Regional Plan is also available on the project website at: www.partnershipforgrowth.ca Saskatoon North Partnership for Growth Regional Plan www.partnershipforgrowth.ca WHY A REGIONAL PLAN? WHO IS THE SASKATOON NORTH PARTNERSHIP FOR GROWTH (P4G)? The P4G includes: OSLER 305 WARMAN • RM of Corman Park 11 r • City of Saskatoon e v MARTENSVILLE i R n a e w katch th Sas u o S • City of Warman 12 Yellow Quill RM OF 16 CORMAN Muskoday PARK • City of Martensville Saulteaux Little Pine Wanuskewin 684 Heritage Park • Town of Osler Moosomin • Saskatoon Regional Economic 41 Development Authority (SREDA) 5 (advisory representation) SASKATOON 14 5 7 16 Regional Oversight Committee Cowessess 219 English River 16 Reserve REEVE JUDY HARWOOD • Corman Park km 11 0 1 2 4 COUNCILLOR BAS FROESE-KOOIJENGA • Corman Park COUNCILLOR RANDY ROOKE • Corman Park Saskatoon North Partnership for Growth Study Area MAYOR CHARLIE CLARK • Saskatoon COUNCILLOR RANDY DONAUER • Saskatoon COUNCILLOR ZACH JEFFRIES • Saskatoon The region’s population could reach 500,000 MAYOR SHERYL SPENCE • Warman in the next 20 years and could grow to COUNCILLOR RICHARD BECK • Warman COUNCILLOR GARY PHILIPCHUK • Warman 1,000,000 in the next 60 years. -

Eagle Heights Country Estates

Eagle Heights Country Estates Applicant: 101120614 Saskatchewan Ltd., c/o Chris Cebryk Address: 103 Baldwin Crescent Saskatoon, SK S7H 3M5 Phone: (306) 717-7457 Email: [email protected] Planning Consultant: Associated Engineering Ltd. 1-2225 Northridge Drive Saskatoon, SK Project Manager: Bill Delainey RPP, MCIP Legal Land Location: SW of Section 11-37-4-W3 and NW of Section 11-37-4-W3 Proposed Number of 95 (in three phases) Lots Average Lot Size 1.0 hectares (2.47 acres) Proposed Lot Density: 0.32 units/acre Development Summary 101120614 Saskatchewan Limited is applying to rezone and subdivide land located in the W½ of Section 11-37-4-W3M within the RM of Corman Park No. 344 for the purpose of developing a 95-lot country residential development. The proposed development comprises 129.5 hectares (320 acres) of land and is known as Eagle Heights Country Estates. The proposed development is located approximately 1.5 km northeast of the City of Saskatoon along Highway 41 directly east of Eagle Ridge Estates. The development site is strategically situated in the Strawberry Hills to take full advantage of the vista views provided from the land to the west and the varied topography combined with the natural vegetation contained on the property lends itself to the accommoda- tion of a variety of housing styles and residential options. The development is intended to exclusively host single detached dwellings on various sized properties maintaining a minimum average of 1 hectare (2.47 acres) within the three planned phases of development. The proposed residential subdivision has been specifically designed to positively integrate with and complement Eagle Ridge Estates which is located directly west of the development site. -

Saskatoon to Regina Via Lake Diefenbaker Saskatoon to Regina Via Lake Diefenbaker

Saskatoon to Regina via Lake Diefenbaker Saskatoon to Regina via Lake Diefenbaker SAILS, SHORES, AND SHIFTING SANDS Saskatoon to Regina via Lake Diefenbaker While Hwy #11 is the main thoroughfare between Saskatoon and Regina, an alternate route just to the west takes you through significantly different countryside including sand hills, wildlife refuges, three provincial parks, one of the world’s largest earth-filled dams, impres- sive sand dunes, and southern Saskatchewan’s largest lake. Most of this route is paved, with the exception of a few access roads. From Saskatoon, begin by taking Hwy #219 south, known as the Chief Whitecap Trail. About 13 km south of the city, you come to Beaver Creek Conservation Area where Beaver Creek meets the South Saskatchewan River. Displays in the interpre- tive centre introduce you to the flora and fauna you might see while walking the 8 km of trails that wind through natural prairie, forested valley slopes, along the mean- dering creek, and beside the sandy riverbank. South of Beaver Creek, the terrain is marked by hummocky sand hills with low shrubs and wooded coulees, and is mostly used for pasture. About 26 km south of Saskatoon, the highway passes through the Whitecap Dakota First Nation, famous for the Dakota Dunes Golf Links, rated among Canada’s top golf courses. Watch for the turn-off to the west to Round Prairie Cemetery, about 19 km south of Whitecap. The Round Prairie area was settled in the 1850s by makes a sharp turn to the west, ending at the junction with Hwy #44 Métis, and was one of the larger Métis settlements (N 51.28501 W 106.82378), just east of Gardiner Dam. -

Saskatoon Sports Facility Guide

SASKATOON SPORTS FACILITY GUIDE 1 Welcome to Saskatoon, your four-season with an sport destination! Saskatoon is a city of tremendous growth and innovation. Each year, visitors travel from across Canada and from all over the world to experience Saskatoon’s natural beauty and sample its unique menu of festivals, cultures, dining, shopping and sport events; to experience open heart the spirit and character that is Saskatoon. Saskatoon has a reputation for hosting memorable sporting events of all sizes. The city boasts incredible sports facilities, accommodations, attractions and restaurants. Saskatoon is capable of hosting events of and vibrant all magnitudes, from local tournaments to world class international competitions. The diversity of culture in Saskatoon is what truly distinguishes this city from all others. The community’s volunteer spirit is well known throughout the country for embracing an event, accommodating athlete and visitor needs and ensuring a truly successful event. It is common for Saskatoon to break event records, energy setting the bar for other communities. Sports are at the heart of Saskatoon, from minor softball leagues to the beloved Saskatoon Blades Western Hockey League franchise to the numerous events held in the city each year, attracting hundreds of volunteers and thousands of fans. Saskatoon’s sports Saskatoon scene is supported by a number of competitive, world-class sports organizations, including Sask Sport Inc., the Saskatoon Sports Council and Saskatoon Sports Tourism. Saskatoon Sports Tourism is a community organization dedicated to welcomes building the sports tourism industry in Saskatoon. If you are interested in bidding, planning or expanding a sporting event in Saskatoon, contact us today! We invite you to visit beautiful Saskatoon! the world Saskatoon Sports Tourism 101 – 202 4th Avenue North, Saskatoon, SK S7K 0K1 SASKATOONSPORTSTOURISM.COM I Toll Free: 1.800.567.2444 2 3 WINTER SPORTS premium Introducing sports facilities Sports are exciting, exhilarating, electric. -

University Diversity

ON CAMPUS NEWS news.usask.ca FEB. 14, 2020 Volume 27, Issue 6 UNIVERSITY DIVERSITY From Black History Month to Indigenous Achievement Week, international student success and the upcoming One Day for Students fundraiser, we tell some of the stories of University of Saskatchewan students and staff with diverse backgrounds, coming from across the province and around the world. USask’s diversity enhances the university’s vibrant campus culture, while educating students for the opportunities of tomorrow. SEE PAGES 4-5, 8-9, 13-14. — 3 — — 6 — — 14 — GIVE PEAS A CHANCE CLIMATE CHANGE ONE DAY FOR STUDENTS Publication Mail Agreement #40065156 Pediatric residency program begins in Regina KRISTEN MCEWEN Saskatchewan now has its first degree before applying to medical Regina-based pediatrics residency school, which is a four-year program. On Campus News is published 12 times program. Once students have completed per year by University of Saskatchewan In July, two pediatric residents medical school, they are required Marketing and Communications. It is started their training at the Univer- to complete residency programs, distributed to all USask faculty, staff, graduate students and members of sity of Saskatchewan (USask) College which can be between two and seven governing bodies, as well as to others of Medicine Regina campus, where years depending on the specialty. in the university community, related roughly 30 per cent of all USask While residents have always organizations, some Saskatchewan medical students train each year. travelled between the cities and to government officials and news media. “We’re excited to have residents sites across the province for their Subscriptions are available for $24 based here,” said Dr. -

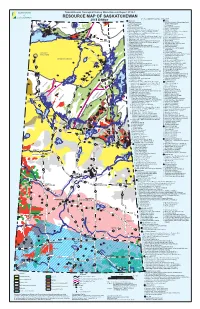

Mineral Resource Map of Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan Geological Survey Miscellaneous Report 2018-1 RESOURCE MAP OF SASKATCHEWAN KEY TO NUMBERED MINERAL DEPOSITS† 2018 Edition # URANIUM # GOLD NOLAN # # 1. Laird Island prospect 1. Box mine (closed), Athona deposit and Tazin Lake 1 Scott 4 2. Nesbitt Lake prospect Frontier Adit prospect # 2 Lake 3. 2. ELA prospect TALTSON 1 # Arty Lake deposit 2# 4. Pitch-ore mine (closed) 3. Pine Channel prospects # #3 3 TRAIN ZEMLAK 1 7 6 # DODGE ENNADAI 5. Beta Gamma mine (closed) 4. Nirdac Creek prospect 5# # #2 4# # # 8 4# 6. Eldorado HAB mine (closed) and Baska prospect 5. Ithingo Lake deposit # # # 9 BEAVERLODGE 7. 6. Twin Zone and Wedge Lake deposits URANIUM 11 # # # 6 Eldorado Eagle mine (closed) and ABC deposit CITY 13 #19# 8. National Explorations and Eldorado Dubyna mines 7. Golden Heart deposit # 15# 12 ### # 5 22 18 16 # TANTATO # (closed) and Strike deposit 8. EP and Komis mines (closed) 14 1 20 #23 # 10 1 4# 24 # 9. Eldorado Verna, Ace-Fay, Nesbitt Labine (Eagle-Ace) 9. Corner Lake deposit 2 # 5 26 # 10. Tower East and Memorial deposits 17 # ###3 # 25 and Beaverlodge mines and Bolger open pit (closed) Lake Athabasca 21 3 2 10. Martin Lake mine (closed) 11. Birch Crossing deposits Fond du Lac # Black STONY Lake 11. Rix-Athabasca, Smitty, Leonard, Cinch and Cayzor 12. Jojay deposit RAPIDS MUDJATIK Athabasca mines (closed); St. Michael prospect 13. Star Lake mine (closed) # 27 53 12. Lorado mine (closed) 14. Jolu and Decade mines (closed) 13. Black Bay/Murmac Bay mine (closed) 15. Jasper mine (closed) Fond du Lac River 14.