The Hawaiian Usage Exception to the Common Law: an Inoculation Against the Effects of Western Influence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No. 24 Mormon Pacific Historical Society

Mormon Pacific Historical Society Proceedings 24th Annual Conference October 17-18th 2003 (Held at ‘Auwaiolimu Chapel in Honolulu) ‘Auwaiolimu Chapel (circa 1890’s) Built by Elder Matthew Noall Dedicated April 29, 1888 (attended by King Kalakaua and Queen Kapi’olani) 1 Mormon Pacific Historical Society 2003 Conference Proceedings October 17-18, 2003 Auwaiolimu (Honolulu) Chapel Significant LDS Historical Sites on Windward Oahu……………………………….1 Lukewarm in Paradise: A Mormon Poi Dog Political Journalist’s Journey ……..11 into Hawaii Politics Alf Pratte Musings of an Old “Pol” ………………………………………………………………32 Cecil Heftel World War Two in Hawaii: A watershed ……………………………………………36 Mark James It all Started with Basketball ………………………………………………………….60 Adney Komatsu Mormon Influences on the Waikiki entertainment Scene …………………………..62 Ishmael Stagner My Life in Music ……………………………………………………………………….72 James “Jimmy” Mo’ikeha King’s Falls (afternoon fieldtrip) ……………………………………………………….75 LDS Historical Sites (Windward Oahu) 2 Pounders Beach, Laie (narration by Wylie Swapp) Pier Pilings at Pounders Beach (Courtesy Mark James) Aloha …… there are so many notable historians in this group, but let me tell you a bit about this area that I know about, things that I’ve heard and read about. The pilings that are out there, that you have seen every time you have come here to this beach, are left over from the original pier that was built when the plantation was organized. They were out here in this remote area and they needed to get the sugar to market, and so that was built in order to get the sugar, and whatever else they were growing, to Honolulu to the markets. These (pilings) have been here ever since. -

Daughters of Hawaiʻi Calabash Cousins

Annual Newsletter 2018 • Volume 41 Issue 1 Daughters of Hawaiʻi Calabash Cousins “...to perpetuate the memory and spirit of old Hawai‘i and of historic facts, and to preserve the nomenclature and correct pronunciation of the Hawaiian language.” The Daughters of Hawaiʻi request the pleasure of Daughters and Calabash Cousins to attend the Annual Meeting on Wednesday, February 21st from 10am until 1:30pm at the Outrigger Canoe Club 10:00 Registration 10:30-11:00 Social 11:00-12:00 Business Meeting 12:00-1:00 Luncheon Buffet 1:00-1:30 Closing Remarks Reservation upon receipt of payment Call (808) 595-6291 or [email protected] RSVP by Feb 16th Cost: $45 Attire: Whites No-Host Bar Eligibility to Vote To vote at the Annual Meeting, a Daughter must be current in her annual dues. The following are three methods for paying dues: 1) By credit card, call (808) 595-6291. 2) By personal check received at 2913 Pali Highway, Honolulu HI 96817-1417 by Feb 15. 3) By cash or check at the Annual Meeting registration (10-10:30am) on February 21. If unable to attend the Annual Meeting, a Daughter may vote via a proxy letter: 1) Identify who will vote on your behalf. If uncertain, you may choose Barbara Nobriga, who serves on the nominating committee and is not seeking office. 2) Designate how you would like your proxy to vote. 3) Sign your letter (typed signature will not be accepted). 4) Your signed letter must be received by February 16, 2017 via post to 2913 Pali Highway, Honolulu HI 96817-1417 or via email to [email protected]. -

U.S. House Report 32 for H.R. 4221 (Feb 1959)

86TH CONoRESS L HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES REPORT 1st Session No. 32 HAWAII STATEHOOD FEBRUARY 11, 1959.-Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed Mr. AsPINALL, from the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, submitted the following REPORT [To accompany H.R. 4221] The Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, to whom was referred the bill (H.R. 4221) to provide for the admission of the State of Hawaii into the Union, having considered the same, report favorably thereon without amendment and recommend that the bill do pass. The purpose of H.R. 4221, introduced by Representative O'Brien of New York, is to provide for the admission of the State of Hawaii into the Union. This bill and its two companions-H.R. 4183 by Delegate Burns and H.R. 4228 by Representative Saylor-were introduced following the committee's consideration of 20 earlier 86th Congress bills and include all amendments adopted in connection therewith. These 20 bills are as follows: H.R. 50, introduced by Delegate Burns; H.R. 324, introduced by Representative Barrett; H.R. 801, introduced by Representative Holland; H.R. 888, introduced by Representative O'Brien of New York; H.R. 954, introduced by Representative Saylor; H.R. 959, introduced by Representative Sisk; H.R. 1106, introduced by Representative Berry; H.R. 1800, introduced by Repre- sentative Dent; H.R. 1833, introduced by Representative Libonati; H.R. 1917, introduced by Representative Green of Oregon; H.R. 1918, introduced by Representative Holt; H.R. 2004, introduced by Representative Younger; .H.R. -

U.S. House Report 32 for H.R. 4221

2d Session No. 1564 AMENDING CERTAIN LAWS OF THE UNITED STATES IN LIGHT OF THE ADMISSION OF TIlE STATE OF HAWAII INTO THE UNION MAY 2, 1960.-Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed Mr. O'BRIEN of New York, from the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, submitted the following REPORT [To accompany H.R. 116021 The Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, to whom was re- ferred the bill (H.R. 11602) to amend certain laws of the United States in light of the admission of the State of Hawaii into the Union, and for other purposes, having considered the same, report favorably thereon without amendment and recommend that the bill do pass. INTRODUCTION IT.R. 11602 was introduced by Representative Inouye after hearings on five predecessor bills (H.R. 10434 by Representative. Aspinall, H.R. 10443 by Congressman Inouye, H.R. 10456 by Representative O'Brien of New York, H.R. 10463 by Representative Saylor, and H.R. 10475 by Representative Westland). H.R. 11602 includes the amend- ments agreed upon in committee when H.R. 10443 was marked up. All of the predecessor bills except H.R. 10443 were identical and were introduced as a result of an executive communication from the Deputy Director of the Bureau of the Budget dated February 12, 1960, en- closing a draft of a bill which he recommended be enacted. This draft bill had been prepared after consultation with all agencies of t.th executive branch administering Federal statutes which were, or might be thought to have been, affected by the admission of Iawaii into the Union on August 24, 1959. -

Outrigger Enterprises and Holiday Inn.Pub

Waikīkī Improvement Association Volume X1, No. 32 Waikīkī Wiki Wiki Wire August 12-18, 2010 Outrigger Enterprises Group joins forces with Holiday Inn Ohana Waikiki Beachcomber hotel to become Holiday Inn Waikiki Beachcomber Resort Outrigger Enterprises Group, Hawai‘i’s largest locally owned hotel operator, and IHG (InterContinental Hotels Group) [LON:IHG, NYSE:IHG (ADRs)], the world’s largest hotel group by number of rooms, today announced the signing of a license agreement to rebrand the OHANA Waikiki Beachcomber hotel as the Holiday Inn Waikiki Beachcomber Resort. The rebranding is expected to be complete in November 2010. Outrigger will continue to own and manage the rebranded resort, bringing its unparalleled reputation for delivering a high-quality guest experience coupled with distinctive “Hawaiian” hospitality to the power and global appeal of the Holiday Inn® brand. All employees will keep their jobs and will remain employees of Outrigger Hotels Hawaii, with Dean Nakasone continuing as general manager overseeing the brand transition. Additionally, the resort’s existing tenants – including Jimmy Buffett’s at the Beachcomber and Magic of Polynesia – will remain in place. “We are proud to include Holiday Inn – and its exciting look, feel and guest experience – as part of our family of quality Outrigger hotels,” said David Carey, president & CEO of Outrigger Enterprises Group. “The new Holiday Inn Waikiki Beachcomber Resort combines Outrigger’s legendary hotel management expertise with Holiday Inn’s iconic brand strength and the 52 -

STATE of HAWAII DEPARTMENT of LAND and NATURAL RESOURCES Land Division Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 June 23, 2017 Board of Land and Na

STATE OF HAWAII DEPARTMENT OF LAND AND NATURAL RESOURCES Land Division Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 June 23, 2017 Board of Land and Natural Resources PSF No.: 16SD-160 State of Hawaii Honolulu, Hawaii OAHU Issuance of Right-of-Entry Permit to United States on Encumbered Land Onshore at Makua Beach and Unencumbered Submerged Lands Offshore of Makua Beach at Kahanahaiki, Waianae, Island of Oahu, Tax Map Key: (1) 8-1-001 :portion of 008 and seaward of 008. APPLICANT: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Honolulu District LEGAL REFERENCE: Sections 171-55, Hawaii Revised Statutes, as amended. LOCATION: Portion of Government fast lands at Makua Beach, Kaena Point State Park, and submerged lands offshore of Makua Beach, Kahanahaiki, Waianae, Island of Oahu, identified by Tax Map Key: (1) 8-1-001: portion of 008 and (1) 8-1-001: seaward of 008, as shown on the attached map labeled Exhibit A. AREA: Fast lands: 6.9 acres, more or less, TMK (1) 8-1-008-1:portion of 008. Submerged lands: 20 acres, more or less, seaward of TMK (1) 8-1-008-1:008. ZONING: State Land Use District: Conservation City & County of Honolulu CZO: N A D-9 BLNR - Issuance of ROE to Page 2 June 23, 2017 United States for Submerged Land TRUST LAND STATUS: Section 5(b) lands of the Hawaii Admission Act. DHHL 3000 entitlement lands pursuant to the Hawaii State Constitution: YES NO X CURRENT USE STATUS: Fast lands: Set aside by Governor’s Executive Order 3338 for Kaena Point State Park. Submerged lands: Unencumbered. -

Nā Pōhaku Ola Kapaemāhū a Kapuni: Performing for Stones at Tupuna Crossings in Hawaiʻi

NĀ PŌHAKU OLA KAPAEMĀHŪ A KAPUNI: PERFORMING FOR STONES AT TUPUNA CROSSINGS IN HAWAIʻI A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN PACIFIC ISLANDS STUDIES MAY 2019 By Teoratuuaarii Morris Thesis Committee: Alexander D. Mawyer, Chairperson Terence A. Wesley-Smith Noenoe K. Silva Keywords: place, stones, Waikīkī, Hawaiʻi, Kahiki, history, Pacific, protocol, solidarity © 2019 Teoratuuaarii Morris ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis would not be possible without the many ears and hands that lifted it (and lifted me) over its development. I would like to thank Dr. Alexander Mawyer for being the Committee Chair of this thesis and giving me endless support and guidance. Thank you for being gracious with your time and energy and pushing me to try new things. Thank you to Dr. Noenoe K. Silva. Discussions from your course in indigenous politics significantly added to my perspectives and your direct support in revisions were thoroughly appreciated. Thank you as well to Dr. Terence Wesley-Smith for being a kind role model since my start in Pacific scholarship and for offering important feedback from the earliest imaginings of this work to its final form. Māuruuru roa to Dr. Jane Moulin for years of instruction in ‘ori Tahiti. These hours in the dance studio gave me a greater appreciation and a hands-on understanding of embodied knowledges. Mahalo nui to Dr. Lilikalā Kameʻeleihiwa for offering critical perspectives in Oceanic connections through the study of mythology. These in-depth explorations helped craft this work, especially in the context of Waikīkī and sacred sites. -

Cultural Tourism and Post-Colonialism in Hawaii Leigh Nicole Schuler University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Anthropology Undergraduate Honors Theses Anthropology 5-2015 Cultural Tourism and Post-Colonialism in Hawaii Leigh Nicole Schuler University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/anthuht Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Schuler, Leigh Nicole, "Cultural Tourism and Post-Colonialism in Hawaii" (2015). Anthropology Undergraduate Honors Theses. 2. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/anthuht/2 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Cultural Tourism and Post-Colonialism in Hawaii An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors Studies in Anthropology By Nicole Schuler Spring 2015 Anthropology J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences The University of Arkansas Acknowledgments I would like to graciously thank Dr. Kirstin Erickson for her encouragement, guidance, and friendship throughout this research. Dr. Erickson motivated me with constructive criticism and suggestions to make my work the best it could be. Under her tutelage, I feel I have matured as a writer and an anthropologist. Dr. Erickson was always available to me when I had questions. Without her help, I would not have received the Honors College Research Grant to travel to Hawaii to conduct my fieldwork. Dr. Erickson was always kind and understanding throughout the two years we have worked together on this research. She was always excited to hear the latest development in my work and supported me with each new challenge. -

The Aliʻi, the Missionaries and Hawaiʻi

The Aliʻi, the Missionaries and Hawaiʻi Hawaiian Mission Houses’ Strategic Plan themes note that the collaboration between Native Hawaiians and American Protestant missionaries resulted in the • The introduction of Christianity; • The development of a written Hawaiian language and establishment of schools that resulted in widespread literacy; • The promulgation of the concept of constitutional government; • The combination of Hawaiian with Western medicine, and • The evolution of a new and distinctive musical tradition (with harmony and choral singing). The Aliʻi, the Missionaries and Hawaiʻi The Aliʻi, the Missionaries and Hawaiʻi On October 23, 1819, the Pioneer Company of American Protestant missionaries from the northeast US, led by Hiram Bingham, set sail on the Thaddeus for the Hawaiian Islands. The Mission Prudential Committee in giving instructions to the pioneers of 1819 said: “Your mission is a mission of mercy, and your work is to be wholly a labor of love. … Your views are not to be limited to a low, narrow scale, but you are to open your hearts wide, and set your marks high. You are to aim at nothing short of covering these islands with fruitful fields, and pleasant dwellings and schools and churches, and of Christian civilization.” (The Friend) Over the course of a little over 40-years (1820-1863 - the “Missionary Period”,) about 180-men and women in twelve Companies served in Hawaiʻi to carry out the mission of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) in the Hawaiian Islands. Collaboration between native Hawaiians and the American Protestant missionaries resulted in, among other things, the introduction of Christianity, the creation of the Hawaiian written language, widespread literacy, the promulgation of the concept of constitutional government, making Western medicine available and the evolution of a new and distinctive musical tradition (with harmony and choral singing). -

The Color of Nationality: Continuities and Discontinuities of Citizenship in Hawaiʻi

The Color of Nationality: Continuities and Discontinuities of Citizenship in Hawaiʻi A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE DECEMBER 2014 By WILLY DANIEL KAIPO KAUAI Dissertation Committee: Neal Milner, Chairperson David Keanu Sai Deborah Halbert Charles Lawrence III Melody MacKenzie Puakea Nogelmeier Copyright ii iii Acknowledgements The year before I began my doctoral program there were less than fifty PhD holders in the world that were of aboriginal Hawaiian descent. At the time I didn’t realize the ramifications of such a grimacing statistic in part because I really didn’t understand what a PhD was. None of my family members held such a degree, and I didn’t know any PhD’s while I was growing up. The only doctors I knew were the ones that you go to when you were sick. I learned much later that the “Ph” in “PhD” referred to “philosophy,” which in Greek means “Love of Wisdom.” The Hawaiian equivalent of which, could be “aloha naʻauao.” While many of my family members were not PhD’s in the Greek sense, many of them were experts in the Hawaiian sense. I never had the opportunity to grow up next to a loko iʻa, or a lo’i, but I did grow up amidst paniolo, who knew as much about makai as they did mauka. Their deep knowledge and aloha for their wahi pana represented an unparalleled intellectual capacity for understanding the interdependency between land and life. -

Mormon Influences on the Waikiki Entertainment Scene

Mormon Influences on the Waikīkī Entertainment Scene by Ishmael W. Stagner, II Before we can discuss the influence of Mormon Hawaiians on the Waikīkī music scene, we need to understand a few things about the development of Hawaiian music and its relationship to things developing in Waikīkī. It is normally thought that the apex of Hawaiian entertaining is being able to entertain on a steady basis in a Waikīkī showroom, or venue. However, this has not always been the case, especially as this relates to the Waikīkī experience. In fact, we need to go back only to the post World War II period to see that entertaining in Waikīkī, especially on a steady basis, was both rare and limited to a very few selected entertainers, most of whom, surprisingly, were not Hawaiian. There were a number of reasons for this, but the main reason for the scarcity of Hawaiian, or Polynesian entertainers in Waikīkī in any great number, goes back to the history of Waikīkī itself. At the turn of the 20th century, Waikīkī was still mostly a swamp, filled with taro patches, rice paddies and fish ponds. We have only to look at the pictures of Ray Jerome Baker, the great photographer of early 20th century Honolulu, to see that Waikīkī was, first and foremost, a bread basket area whose lowlands were the delta areas for the run-off waters of Mānoa, Pauoa, and Pālolo streams. As such, Waikīkī fed much of what we call East Oahu, and rivaled the food production and water-storage capacities of better-known farming areas such as Kāne‘ohe, Kahalu‘u and Waiāhole. -

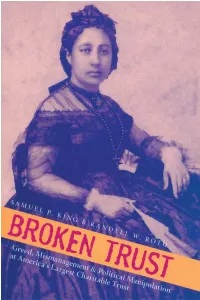

Broken Trust

Introduction to the Open Access Edition of Broken Trust Judge Samuel P. King and I wrote Broken Trust to help protect the legacy of Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop. We assigned all royal- ties to local charities, donated thousands of copies to libraries and high schools, and posted source documents to BrokenTrustBook.com. Below, the Kamehameha Schools trustees explain their decision to support the open access edition, which makes it readily available to the public. That they chose to do so would have delighted Judge King immensely, as it does me. Mahalo nui loa to them and to University of Hawai‘i Press for its cooperation and assistance. Randall W. Roth, September 2017 “This year, Kamehameha Schools celebrates 130 years of educating our students as we strive to achieve the thriving lāhui envisioned by our founder, Ke Ali‘i Bernice Pauahi Bishop. We decided to participate in bringing Broken Trust to an open access platform both to recognize and honor the dedication and courage of the people involved in our lāhui during that period of time and to acknowledge this significant period in our history. We also felt it was important to make this resource openly available to students, today and in the future, so that the lessons learned might continue to make us healthier as an organization and as a com- munity. Indeed, Kamehameha Schools is stronger today in governance and structure fully knowing that our organization is accountable to the people we serve.” —The Trustees of Kamehameha Schools, September 2017 “In Hawai‘i, we tend not to speak up, even when we know that some- thing is wrong.