Biden's China Strategy: Coalition-Driven Competition Or

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reaching Beyond the Ivory Tower: a “How To” Manual *

Reaching Beyond the Ivory Tower: A “How To” Manual * Daniel Byman and Matthew Kroenig Security Studies (forthcoming, June 2016) *For helpful comments on earlier versios of this article, the authors would like to thank Michael C. Desch, Rebecca Friedman, Bruce Jentleson, Morgan Kaplan, Marc Lynch, Jeremy Shapiro, and participants in the Program on International Politics, Economics, and Security Speaker Series at the University of Chicago, participants in the Nuclear Studies Research Initiative Launch Conference, Austin, Texas, October 17-19, 2013, and members of a Midwest Political Science Association panel. Particular thanks to two anonymous reviewers and the editors of Security Studies for their helpful comments. 1 Joseph Nye, one of the rare top scholars with experience as a senior policymaker, lamented “the walls surrounding the ivory tower never seemed so high” – a view shared outside the academy and by many academics working on national security.1 Moreover, this problem may only be getting worse: a 2011 survey found that 85 percent of scholars believe the divide between scholars’ and policymakers’ worlds is growing. 2 Explanations range from the busyness of policymakers’ schedules, a disciplinary shift that emphasizes theory and methodology over policy relevance, and generally impenetrable academic prose. These and other explanations have merit, but such recommendations fail to recognize another fundamental issue: even those academic works that avoid these pitfalls rarely shape policy.3 Of course, much academic research is not designed to influence policy in the first place. The primary purpose of academic research is not, nor should it be, to shape policy, but to expand the frontiers of human knowledge. -

Politics of Coalition in India

Journal of Power, Politics & Governance March 2014, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 01–11 ISSN: 2372-4919 (Print), 2372-4927 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2014. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development Politics of Coalition in India Farooq Ahmad Malik1 and Bilal Ahmad Malik2 Abstract The paper wants to highlight the evolution of coalition governments in india. The evaluation of coalition politics and an analysis of how far coalition remains dynamic yet stable. How difficult it is to make policy decisions when coalition of ideologies forms the government. More often coalitions are formed to prevent a common enemy from the government and capturing the power. Equally interesting is the fact a coalition devoid of ideological mornings survives till the enemy is humbled. While making political adjustments, principles may have to be set aside and in this process ideology becomes the first victim. Once the euphoria victory is over, differences come to the surface and the structure collapses like a pack of cards. On the grounds of research, facts and history one has to acknowledge india lives in politics of coalition. Keywords: india, government, coalition, withdrawal, ideology, partner, alliance, politics, union Introduction Coalition is a phenomenon of a multi-party government where a number of minority parties join hands for the purpose of running the government which is otherwise not possible. A coalition is formed when many groups come into common terms with each other and define a common programme or agenda on which they work. A coalition government always remains in pulls and pressures particularly in a multinational country like india. -

International Relations in a Changing World: a New Diplomacy? Edward Finn

INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS IN A CHANGING WORLD: A NEW DIPLOMACY? EDWARD FINN Edward Finn is studying Comparative Literature in Latin and French at Princeton University. INTRODUCTION The revolutionary power of technology to change reality forces us to re-examine our understanding of the international political system. On a fundamental level, we must begin with the classic international relations debate between realism and liberalism, well summarised by Stephen Walt.1 The third paradigm of constructivism provides the key for combining aspects of both liberalism and realism into a cohesive prediction for the political future. The erosion of sovereignty goes hand in hand with the burgeoning Information Age’s seemingly unstoppable mechanism for breaking down physical boundaries and the conceptual systems grounded upon them. Classical realism fails because of its fundamental assumption of the traditional sovereignty of the actors in its system. Liberalism cannot adequately quantify the nebulous connection between prosperity and freedom, which it assumes as an inherent truth, in a world with lucrative autocracies like Singapore and China. Instead, we have to accept the transformative power of ideas or, more directly, the technological, social, economic and political changes they bring about. From an American perspective, it is crucial to examine these changes, not only to understand their relevance as they transform the US, but also their effects in our evolving global relationships.Every development in international relations can be linked to some event that happened in the past, but never before has so much changed so quickly at such an expansive global level. In the first section of this article, I will examine the nature of recent technological changes in diplomacy and the larger derivative effects in society, which relate to the future of international politics. -

The China Relief Expedition Joint Coalition Warfare in China Summer 1900

07-02574 China Relief Cover.indd 1 11/19/08 12:53:03 PM 07-02574 China Relief Cover.indd 2 11/19/08 12:53:04 PM The China Relief Expedition Joint Coalition Warfare in China Summer 1900 prepared by LTC(R) Robert R. Leonhard, Ph.D. The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory This essay reflects the views of the author alone and does not necessarily imply concurrence by The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHU/APL) or any other organization or agency, public or private. About the Author LTC(R) Robert R. Leonhard, Ph.D., is on the Principal Professional Staff of The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory and a member of the Strategic Assessments Office of the National Security Analysis Department. He retired from a 24-year career in the Army after serving as an infantry officer and war planner and is a veteran of Operation Desert Storm. Dr. Leonhard is the author of The Art of Maneuver: Maneuver-Warfare Theory and AirLand Battle (1991), Fighting by Minutes: Time and the Art of War (1994), The Principles of War for the Informa- tion Age (1998), and The Evolution of Strategy in the Global War on Terrorism (2005), as well as numerous articles and essays on national security issues. Foreign Concessions and Spheres of Influence China, 1900 Introduction The summer of 1900 saw the formation of a perfect storm of conflict over the northern provinces of China. Atop an anachronistic and arrogant national government sat an aged and devious woman—the Empress Dowager Tsu Hsi. -

The 'Great Debates' in International Relations Theory

The ‘Great Debates’ in international relations theory Written by IJ Benneyworth This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. The ‘Great Debates’ in international relations theory https://www.e-ir.info/2011/05/20/the-%e2%80%98great-debates%e2%80%99-in-international-relations-theory/ IJ BENNEYWORTH, MAY 20 2011 International relations in the most basic sense have existed since neighbouring tribes started throwing rocks at, or trading with, each other. From the Peloponnesian War, through European poleis to ultimately nation states, Realist trends can be observed before the term existed. Likewise the evolution of Liberalist thinking, from the Enlightenment onwards, expressed itself in calls for a better, more cooperative world before finding practical application – if little success – after The Great War. It was following this conflict that the discipline of International Relations (IR) emerged in 1919. Like any science, theory was IR’s foundation in how it defined itself and viewed the world it attempted to explain, and when contradictory theories emerged clashes inevitably followed. These disputes throughout IR’s short history have come to be known as ‘The Great Debates’, and though disputed it is generally felt there have been four, namely ‘Realism/Liberalism’, ‘Traditionalism/Behaviouralism’, ‘Neorealism/Neoliberalism’ and the most recent ‘Rationalism/Reflectivism’. All have had an effect on IR theory, some greater than others, but each merit analysis of their respective impacts. First we shall briefly explore the historical development of IR theory then critically assess each Debate before concluding. -

Coalition Governments and Policy Distortions : the Indian Experience Bhaskar Dutta

Coalition Governments and Policy Distortions : The Indian Experience Bhaskar Dutta I. Introduction Much of the recent policy discussion in India implicitly assumes a framework in which a benevolent government or social planner will optimally choose policy instruments in order to maximise the welfare of the representative individual, with the availabilitv of resources posing , f / r b I am most grateful to as the main constraint. This normative Sanghamitra Daiand Bharat view of government behaviour is, of Ramaswami for numerous course, an important tool of analysis. discussions and invaluable advice. However, it can often be a sterile exercise Thanks are also due to IRIS if it ignores completely the institutional University of Maryland for constraints and rigidities in which policy- financial support. making occurs. The presence of these constraints makes it important to analyse the positive theory of government behaviour, or in other words to explore what governments actually do. The recent public choice literature discusses various political features which crucially influence government behaviour, and which drive a wedge between what governments actually do and what they are advised to do by economists. Typically, political power is dispersed, either across different wings of the government, or amongst political parties in a coalition, or across parties that alternate in power through the medium of elections. The desire to concentrate or hold on to power can result in inefficient economic policies. For instance, lobbying by various interest groups together with the ruling party's wish to remain in power often results in policy distortions being exchanged for electoral support.1 Several papers also emphasise the presence of political cycles in economic policy formulation. -

What Role for IBSA Dialogue Forum? Mehmet Özkan*

January 2011 Journal of Global Analysis Integration in the Global South: What role for IBSA Dialogue Forum? Mehmet Özkan* Recently we have seen that the middle-sized states are coming together in several forums. The WTO meetings and India-Brazil-South Africa (IBSA) dialogue forum are among those to be cited. Such groupings are mainly economy- oriented and whether they will have political output needs to be seen, however, in the future if globalization goes in a similar way as today, we might see more groupings. Those groupings should be seen as reactions to unjust and exclusive globalization. The IBSA Dialogue Forum members have enhanced their relations economically by signing bilateral trade agreements and acting together on economic issues in global forums. If they can hold together, they are creating a market more than ¼ of global population and, if successful, it has a chance to be the engine of growth in the South. Moreover if they can create the biggest market in the South, they would also be influential in the being of the voice of the South. In that sense, this paper addresses the possible ways to develop relations between the IBSA members and economic development in the South, furthermore, implication of the IBSA on global governance and development can be as critical as its contribution to economic development, since the global governing bodies have legitimacy crisis. Keywords: South-South relations, the IBSA Dialogue Forum, pivotal middle power, economic development, international institutions. Mehmet ÖZKAN PhD Scholar Sevilla University, Spain e-mail: [email protected] www.cesran.org * Mehmet ÖZKAN is a PhD Candidate at Sevilla University, Spain focusing on how cultural/religious elements shape the foreign policy mentality in the non-western world, namely in South Africa, Turkey and India. -

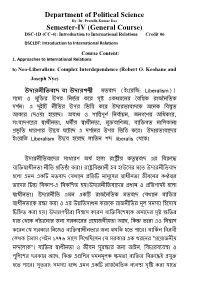

Department of Political Science Semester-IV (General Course)

Department of Political Science By: Dr. Prafulla Kumar Das Semester-IV (General Course) DSC-1D (CC-4): Introduction to International Relations Credit 06 DSC1DT: Introduction to International Relations Course Content: 1. Approaches to International Relations b) Neo-Liberalism: Complex Interdependence (Robert O. Keohane and Joseph Nye) ( : Liberalism)) ও উপ উপ উ ও ও প , , প , , , উ উপ উ Liberalism উ liberalis উ । উ উ - ।উ ও প । উ ও উ । উ প , ও ও প । প ১৭৭৬ " "। ও , ও প , প । প , ও । উ ও উৎ ও প ও প উ উ প , প প ও প প ও উ ও , , ও ও ও , উ , ও , , ও । উ প , ও উ - ৎ , উ প , ও ও । Complex interdependence Complex interdependence in international relations is the idea put forth by Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye. The term "complex interdependence" was claimed by Raymond Leslie Buell in 1925 to describe the new ordering among economies, cultures and races. The very concept was popularized through the work of Richard N. Cooper (1968). With the analytical construct of complex interdependence in their critique of political realism, "Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye go a step further and analyze how international politics is transformed by interdependence" . The theorists recognized that the various and complex transnational connections and interdependencies between states and societies were increasing, while the use of military force and power balancing are decreasing but remain important. In making use of the concept of interdependence, Keohane and Nye also importantly differentiated between interdependence and dependence in analyzing the role of power in politics and the relations between international actors. -

Brazil and China: South-South Partnership Or North-South Competition?

POLICY PAPER Number 26, March 2011 Foreign Policy at BROOKINGS The Brookings Institution 1775 Massachusetts Ave., NW Washington, D.C. 20036 brookings.edu Brazil and China: South-South Partnership or North-South Competition? Carlos Pereira João Augusto de Castro Neves POLICY PAPER Number 26, March 2011 Foreign Policy at BROOKINGS Brazil and China: South-South Partnership or North-South Competition? Carlos Pereira João Augusto de Castro Neves A CKNOWLEDGEMENTS This paper was originally commissioned by CAF. We are very grateful to Ted Piccone, Mauricio Cardenas, Cheng Li, and Octavio Amorim Neto for their comments and valuable suggestions in previous versions of this paper. F OREIGN P OLICY AT B ROOKINGS B RAZIL AND C HINA : S OUTH -S OUTH P ARTNER S HI P OR N ORTH -S OUTH C OM P ETITION ? ii A B STRACT o shed some light on the possibilities and lim- three aspects, but also on the governance structure its of meaningful coalitions among emerging and institutional safeguards in place in both China Tcountries, this paper focuses on Brazil-China and Brazil. The analysis suggests that, even with ad- relations. Three main topics present a puzzle: trade vantageous trade relations, there is a pattern of grow- relations, the political-strategic realm, and foreign di- ing imbalances and asymmetries in trade flows that rect investment. This paper develops a comparative are more favorable to China than Brazil. Therefore, assessment between the two countries in those areas, Brazil and China are bound to be competitors, but it and identifies the extent to which the two emerg- is not clear how bilateral imbalances may affect mul- ing powers should be understood as partners and/or tilateral cooperation between the two countries. -

The Future of Power

Transcript The Future of Power Joseph Nye University Distinguished Service Professor, Harvard University Chair: Sir Jeremy Greenstock Former British Ambassador to the United Nations (1998-2003) 10 May 2011 The views expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of Chatham House, its staff, associates or Council. Chatham House is independent and owes no allegiance to any government or to any political body. It does not take institutional positions on policy issues. This document is issued on the understanding that if any extract is used, the speaker(s) and Chatham House should be credited, preferably with the details of the event. Where this document refers to or reports statements made by speakers at an event every effort has been made to provide a fair representation of their views and opinions, but the ultimate responsibility for accuracy lies with this document’s author(s). The published text of speeches and presentations may differ from delivery. Transcript: The Future of Power Joseph Nye: I’d like to be not a typical professor in the sense of not speaking in fifty-minute bytes at a time, but restrain myself and follow Jeremy’s good instruction. Having been a visitor to Ditchley a few times I know he runs a very tight ship. The argument that I make in this new book about the future of powers, that there are two large power shifts going on in this century. One, I call power transition, which is a shift of power among states, which is largely from West to East. -

Liberalism in a Realist World: International Relations As an American Scholarly Tradition

Liberalism in a Realist World: International Relations as an American Scholarly Tradition G. John Ikenberry The study of international relations (IR) is a worldwide pursuit with each country having its own theoretical orientations, preoccupations and debates. Beginning in the early twentieth century, the US created its own scholarly traditions of IR. Eventually, IR became an American social science with the US becoming the epicentre for a worldwide IR community engaged in a set of research programmes and theoretical debates. The discipline of IR emerged in the US at a time when it was the world’s most powerful state and a liberal great power caught in a struggle with illiberal rivals. This context ensured that the American theoretical debates would be built around both power and liberal ideals. Over the decades, the two grand projects of realism and liberalism struggled to define the agenda of IR in the US. These traditions have evolved as they attempted to make sense of contemporary developments, speak to strategic position of the US and its foreign policy, as well as deal with the changing fashions and stand- ards of social science. The rationalist formulations of realism and liberalism sparked reactions and constructivism has arisen to offer counterpoints to the rational choice theory. Keywords: International Relations Theory, Realism, Liberalism The study of International Relations (IR) is a worldwide pursuit but every country has its own theoretical orientations, preoccupations and debates. This is true for the American experience—and deeply so. Beginning in the early twentieth cen- tury, the US created its own scholarly traditions of IR. -

Coalition Governments in India: the Way Forward

International Journal of Research in Engineering, IT and Social Sciences ISSN 2250-0558, Impact Factor: 6.452, Volume 6 Issue 03, March 2016 Coalition governments in India: The way forward Veena.K Assistant professor, Department of Political Science & Research scholar (BU), Government Arts College, Bangalore -560001 ABSTRACT Indian federal system says clearly the „distribution of power „has been assured by the constitution for the „effective administration‟ and it is reflected in Indian parliamentary democracy. India has a multi party system where there is a number of national and regional political party because of which there is an emergence of coalition governments in India. The governments have been formed at the centre or at the state based on the „First –past- the- post-electoral system‟ in the Indian political system. Electoral politics of India before independence and after independence witnessed major changes in forming government, its running and completing of its tenure. Elections in India will be held once in five years to choose the leader and peoples‟ representatives, wherein the election commission and delimitation commission play significant roles. Indian democratically elected government is chosen by its large population of different sectors such as, region, religion, caste, language etc, but the uneven development of regions and non performance of national parties resulted in rise of regional political parties in India. Regional political parties are the pillars of the coalitions today in making or breaking but capturing the power is the ultimate goal of any of the party. Keywords: Democracy, Political Parties, Coalitions, Politics, Stability, regions, First-Past- The - Post, Governments Indian political system takes place within the framework of a constitution.