Campaigns of Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Sector Development Programme 2019-20 (Original)

GOVERNMENT OF BALOCHISTAN PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT PUBLIC SECTOR DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 2019-20 (ORIGINAL) Table of Contents S.No. Sector Page No. 1. Agriculture……………………………………………………………………… 2 2. Livestock………………………………………………………………………… 8 3. Forestry………………………………………………………………………….. 11 4. Fisheries…………………………………………………………………………. 13 5. Food……………………………………………………………………………….. 15 6. Population welfare………………………………………………………….. 16 7. Industries………………………………………………………………………... 18 8. Minerals………………………………………………………………………….. 21 9. Manpower………………………………………………………………………. 23 10. Sports……………………………………………………………………………… 25 11. Culture……………………………………………………………………………. 30 12. Tourism…………………………………………………………………………... 33 13. PP&H………………………………………………………………………………. 36 14. Communication………………………………………………………………. 46 15. Water……………………………………………………………………………… 86 16. Information Technology…………………………………………………... 105 17. Education. ………………………………………………………………………. 107 18. Health……………………………………………………………………………... 133 19. Public Health Engineering……………………………………………….. 144 20. Social Welfare…………………………………………………………………. 183 21. Environment…………………………………………………………………… 188 22. Local Government ………………………………………………………….. 189 23. Women Development……………………………………………………… 198 24. Urban Planning and Development……………………………………. 200 25. Power…………………………………………………………………………….. 206 26. Other Schemes………………………………………………………………… 212 27. List of Schemes to be reassessed for Socio-Economic Viability 2-32 PREFACE Agro-pastoral economy of Balochistan, periodically affected by spells of droughts, has shrunk livelihood opportunities. -

Public Notice Auction of Gold Ornament & Valuables

PUBLIC NOTICE AUCTION OF GOLD ORNAMENT & VALUABLES Finance facilities were extended by JS Bank Limited to its customers mentioned below against the security of deposit and pledge of Gold ornaments/valuables. The customers have neglected and failed to repay the finances extended to them by JS Bank Limited along with the mark-up thereon. The current outstanding liability of such customers is mentioned below. Notice is hereby given to the under mentioned customers that if payment of the entire outstanding amount of finance along with mark-up is not made by them to JS Bank Limited within 15 days of the publication of this notice, JS Bank Limited shall auction the Gold ornaments/valuables after issuing public notice regarding the date and time of the public auction and the proceeds realized from such auction shall be applied towards the outstanding amount due and payable by the customers to JS Bank Limited. No further public notice shall be issued to call upon the customers to make payment of the outstanding amounts due and payable to JS Bank as mentioned hereunder: Customer ID Customer Name Address Amount as of 8th April 1038553 ZAHID HUSSAIN MUHALLA MASANDPURSHI KARPUR SHIKARPUR 343283.35 1012051 ZEESHAN ALI HYDERI MUHALLA SHIKA RPUR SHIKARPUR PK SHIKARPUR 409988.71 1008854 NANIK RAM VILLAGE JARWAR PSOT OFFICE JARWAR GHOTKI 65110 PAK SITAN GHOTKI 608446.89 999474 DARYA KHAN THENDA PO HABIB KOT TALUKA LAKHI DISTRICT SHIKARPU R 781000 SHIKARPUR PAKISTAN SHIKARPUR 361156.69 352105 ABDUL JABBAR FAZALEELAHI ESTATE S HOP NO C12 BLOCK 3 SAADI TOWN -

A Content Analysis of Current Affairs Talk Shows on Pakistani News Channels

Vol.2 Issue.2 June-2021 Global Media and Social Sciences Research Journal (Quarterly) Page-14-24 Social Sciences Website: http://www.gmssrj.com ISSN:2709-3433 (Online) Multidisciplinar Email:[email protected],[email protected] ISSN:2709-3425 (Print) y A Content Analysis of Current Affairs Talk Shows on Pakistani News Channels Tufail Akram1 Rahman Ullah2 Fazli Wahid3 1BS Student,Department of Journalism & Mass Communication, Kohat University of Science and Technology, Kohat. 2Lecturer, Department of Journalism & Mass Communication, Kohat University of Science and Technology, Kohat. 3Lecturer, Department of Journalism & Mass Communication, Kohat University of Science and Technology, Kohat. Abstract Keywords This study is designed to find out that what are the major themes and Content concepts in the current affair talk shows of Pakistani media. Talk Analysis, shows of news channels provide information and opinion regarding Pakistan, Government Policy, Politics and Socio-economic concerns, Education, Sensationalism, Health and Development etc. To reach the objectives, we adopted Talk Shows, qualitative methodology with thematic analysis to analyze the contents Tv Channels, broadcasted in seven different current affairs talk shows that on- aired Political Parties, in the prominent television news channel of Pakistan. Total 225 Talk Politics. shows were analyzed during two months (September and October 2020). The seven talk shows were selected through the purposive sampling method included, Capital Talk, Ajj Shahzeb Khanzada ke Sath, 11th Hour, News Eye, Hard Talk Pakistan, Breaking Point with Malick, and On the Front. The finding of the study indicates that the Majority of the time (70 %) was given to political issues and less than 1% of the time given to education, health, development and economy. -

Qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwe

qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfgh jklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvb nmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwer tyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasProfiles of Political Personalities dfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzx cvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuio pasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghj klzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmrty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc 22 Table of Contents 1. Mutahidda Qaumi Movement 11 1.1 Haider Abbas Rizvi……………………………………………………………………………………….4 1.2 Farooq Sattar………………………………………………………………………………………………66 1.3 Altaf Hussain ………………………………………………………………………………………………8 1.4 Waseem Akhtar…………………………………………………………………………………………….10 1.5 Babar ghauri…………………………………………………………………………………………………1111 1.6 Mustafa Kamal……………………………………………………………………………………………….13 1.7 Dr. Ishrat ul Iad……………………………………………………………………………………………….15 2. Awami National Party………………………………………………………………………………………….17 2.1 Afrasiab Khattak………………………………………………………………………………………………17 2.2 Azam Khan Hoti……………………………………………………………………………………………….19 2.3 Asfand yaar Wali Khan………………………………………………………………………………………20 2.4 Haji Ghulam Ahmed Bilour………………………………………………………………………………..22 2.5 Bashir Ahmed Bilour ………………………………………………………………………………………24 2.6 Mian Iftikhar Hussain………………………………………………………………………………………25 2.7 Mohad Zahid Khan ………………………………………………………………………………………….27 2.8 Bushra Gohar………………………………………………………………………………………………….29 -

MEI Report Sunni Deobandi-Shi`I Sectarian Violence in Pakistan Explaining the Resurgence Since 2007 Arif Ra!Q

MEI Report Sunni Deobandi-Shi`i Sectarian Violence in Pakistan Explaining the Resurgence Since 2007 Arif Ra!q Photo Credit: AP Photo/B.K. Bangash December 2014 ! Sunni Deobandi-Shi‘i Sectarian Violence in Pakistan Explaining the Resurgence since 2007 Arif Rafiq! DECEMBER 2014 1 ! ! Contents ! ! I. Summary ................................................................................. 3! II. Acronyms ............................................................................... 5! III. The Author ............................................................................ 8! IV. Introduction .......................................................................... 9! V. Historic Roots of Sunni Deobandi-Shi‘i Conflict in Pakistan ...... 10! VI. Sectarian Violence Surges since 2007: How and Why? ............ 32! VII. Current Trends: Sectarianism Growing .................................. 91! VIII. Policy Recommendations .................................................. 105! IX. Bibliography ..................................................................... 110! X. Notes ................................................................................ 114! ! 2 I. Summary • Sectarian violence between Sunni Deobandi and Shi‘i Muslims in Pakistan has resurged since 2007, resulting in approximately 2,300 deaths in Pakistan’s four main provinces from 2007 to 2013 and an estimated 1,500 deaths in the Kurram Agency from 2007 to 2011. • Baluchistan and Karachi are now the two most active zones of violence between Sunni Deobandis and Shi‘a, -

Persian Manuscripts

: SUPPLEMENT TO THE CATALOGUE OF THE PERSIAN MANUSCRIPTS IN THE BRITISH MUSEUM BY CHARLES RIEU, Ph.D. PRINTED BY ORDER OF THE TRUSTEES Sontion SOLD AT THE BRITISH MUSEUM; AND BY Messrs. LONGMANS & CO., 39, Paternoster Row; R QUARITCH, 15, Piccadilly, W.j A. ASHEE & CO., 13, Bedford .Street, Covent Garden ; KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TRUBNER & CO., Paternoster House, Charing Cross Eoad ; and HENEY FROWDE, Oxford University Press, Amen Corner. 1895. : LONDON printed by gilbert and rivington, limited , st. John's house, clerkenwell, e.g. TUP r-FTTY CFNTEf ; PEE FACE. The present Supplement deals with four hundred and twenty-five Manuscripts acquired by the Museum during the last twelve years, namely from 1883, the year in which the third and last volume of the Persian Catalogue was published, to the last quarter of the present year. For more than a half of these accessions, namely, two hundred and forty volumes, the Museum is indebted to the agency of Mr. Sidney J. A. Churchill, late Persian Secretary to Her Majesty's Legation at Teheran, who during eleven years, from 1884 to 1894, applied himself with unflagging zeal to the self-imposed duty of enriching the National Library with rare Oriental MSS. and with the almost equally rare productions of the printing press of Persia. By his intimate acquaintance with the language and literature of that country, with the character of its inhabitants, and with some of its statesmen and scholars, Mr. Churchill was eminently qualified for that task, and he availed himself with brilliant success of his exceptional opportunities. His first contribution was a fine illuminated copy of the Zafar Namah, or rhymed chronicle, of Hamdullah Mustaufi (no. -

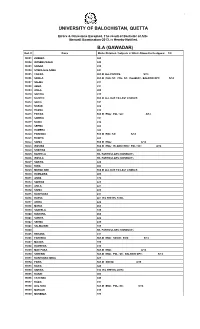

(Gawadar) University of Balochistan, Quetta

1 UNIVERSITY OF BALOCHISTAN, QUETTA Errors & Omissions Excepted. The result of Bachelor of Arts (Annual) Examination-2013, is Hereby Notified. B.A (GAWADAR) Roll. # Name Marks Obtained / Subjects in Which Allowed to Re-Appear. Till 16001 ZUBEDA 425 16002 WASEEA MALIK 448 16003 SHAZIA 430 16004 SYEDA GUL SABA 447 16005 TAHIRA R/A IN ALL PAPERS. S/14 16006 SOHILA R/A IN PAK: ST: POL: SC: ISLAMIAT. BALOCHI OPT: S/14 16007 SALMA 437 16008 AZIZA 411 16009 ANILA 409 16010 SAHIMA 413 16011 NAHEED R/A IN ALL DUE TO LAST CHANCE. 16012 SANIA 391 16013 NAZAN 426 16014 HASNA 432 16015 FARIDA R/A IN ENG: POL: SC: A/14 16016 SAMINA 397 16017 NADIA 418 16018 SEEMA 484 16019 HUMERA 384 16020 FARZANA R/A IN POL: SC: S/14 16021 RUQIYA 424 16022 SAIMA R/A IN ENG: A/14 16023 WASIMA R/A IN ENG: ISLAMIC EDU: POL: SC: A/14 16024 SHAHIDA 404 16025 RAHEELA R/L PARTICULARS (CONDUCT) 16026 WASILA R/L PARTICULARS (CONDUCT) 16027 SABIRA 428 16028 RIZIA 404 16029 MURAD BIBI R/A IN ALL DUE TO LAST CHANCE. 16030 HUMAAIRA 409 16031 ASMA 376 16032 SAEEDA 425 16033 ANILA 421 16034 SAIMA 435 16035 RUKHSANA 411 16036 HAESA 461 R/L FEE RS. 5350/- 16037 ABIDA 424 16038 MARIA 455 16039 SANEELA 399 16040 RIZWANA 450 16041 SURIYA 424 16042 SEEMA 415 16043 SALMA BIBI 395 16044 R/L PARTICULARS (CONDUCT) 16045 REHANA 411 16046 FAREEDA R/A IN ENG: SOCIO: ECO: S/14 16047 MAJIDA 399 16048 HAMEEDA 419 16049 MAH PARA R/A IN ENG: A/14 16050 SHEERIN R/A IN ENG: POL: SC: BALOCHI OPT: S/14 16051 RUKHSANA IQBAL 423 16052 FOZIA R/A IN SOCIO: A/14 16053 NAZIA 428 16054 SAHIRA 414 R/L FEE RS. -

Compilation of Election Promises by Political Parties

Compilation of Election Promises by Political Parties April, 2014 This report was made possible with support from the American people through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the sole responsibility of Centre for Peace and Development Initiatives (CPDI) and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of USAID or the U.S. Government. Contents Introduction: ....................................................................................................................................................... 2 Election Promises by PPP ................................................................................................................................... 3 Election Promises by PML-N ............................................................................................................................... 9 Election Promises by PTI ...................................................................................................................................24 Election Promises by MQM ..............................................................................................................................33 Election Promises by JUI-F ................................................................................................................................39 Election Promises by JAMAAT-E-ISLAMI ..........................................................................................................43 pg. 1 Introduction: Elections are not be-all and end-all of the democratic process. -

BEHIND BARS Javed Nomani

BEHIND BARS Javed Nomani Reproduced by Sani H. Panhwar BEHIND BARS Javed Nomani Reproduced by Sani H. Panhwar (2020) CONTENTS About the author .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 1 Introduction .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 2 Translator's Note .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 5 Foreword .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 6 Torture Cells .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 7 Karachi Central Jail .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 19 Sukkur Jail .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 27 Hyderabad Central Jail .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 52 Return to Karachi Central Jail .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 82 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Maulana Javed Nomani, 32, was born in a small village, Hujjan, to the south of Sargodha where his parents came to settle from East Punjab after the partition of India. His father Rao Abdul Jabbar, a middle-class peasant, is a well-known political worker of the locality. In 1977 he contested the provincial assembly polls as a candidate of the Jamiat-Ulamae Islam (JUI). Javed Nomani got his primary education from the local village school and later went to Sargodha High School. His normal studies were, however, discontinued when he shifted to Madressa-e-Arabia Islamia, Burewala, for religious education. He came to Karachi in 1977 to continue his studies in Jamia Uloom-e-Islamia, Binauri Town, where he was inducted in the struggle that was raging against the military dictatorship of General Ziaul Haque. As Zia cracked down harshly on the democratic forces, Maulana Nomani went into exile in Kabul. On his return in 1983, he was arrested at Karachi airport, from where the book takes the reader into his ordeal over the next three years. ****** I am pleased at your decision to present before the Pakistani nation and the world community an account of your experience of torture cells in a military dictatorship. -

Pakistan Engineering Council List of Contractor's Firms in Sindh 2017-18

Pakistan Engineering Council List Of Contractor's Firms in Sindh 2017-18 Sr # Cat Reg # Firm Name Validity City Phone Email 1 C1 5 GREAVES PAKISTAN (PVT) LTD Jun 30, 2018 KARACHI 02135682565-7 [email protected] 2 CA 9 SIEMENS PAKISTAN ENGG CO LTD Jun 30, 2018 KARACHI 3222224645 [email protected] 3 OA 10 PAK OASIS INDUSTRIES (PVT) LTD Jun 30, 2018 KARACHI 2132414319 [email protected] 4 C2 12 PROCON (PVT) LTD Jun 30, 2018 KARACHI 2135840848 [email protected] 5 C3 15 SEASONMASTER ENGINEERING (PVT) LTD. Jun 30, 2018 KARACHI 5396351-3 [email protected]. 6 O2 16 S.D ENTERPRISES Jun 30, 2018 KARACHI 7 CA 22 RAMZAN AND SONS (PVT) LTD Jun 30, 2018 KARACHI 02135821861-62 [email protected] 8 O2 23 GOOD LUCK ENTERPRISES Jun 30, 2018 KARACHI 9 O2 25 DEOKJAE CONSTRUCTION COMPANY (PVT) LTD. Jun 30, 2018 KACHHI 2135860985 [email protected] 10 CA 27 SAITA (PAKISTAN) PTE LTD Jun 30, 2019 KARACHI 021-34548577 saita @cyber.net.pk 11 CB 29 JAMMY CONSTRUCTORS (PVT) LTD Jun 30, 2018 KARACHI 2134551671 [email protected] 12 O3 31 ALLIED ENGINEERING & SERVICES (PVT) LTD Jun 30, 2018 KARACHI 0215066901-13 [email protected]/www.aesl.com.pk 13 C1 36 NAWAB BROTHERS (PVT) LTD Jun 30, 2018 KARACHI 2136724061 [email protected] 14 O1 40 KOHISAR ENTERPRISES Jun 30, 2018 KARACHI 2135685005 [email protected] 15 O3 42 CONTRACT PLUS Jun 30, 2018 KARACHI 3018268003 16 O1 42 ABDUL QAYOOM MAZARI Jun 30, 2018 KASHMORE 3337366688 [email protected] 17 CA 43 USMANI INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATESPVT LTD Jun 30, 2018 KARACHI 02135653501-3 [email protected] -

Regime Type and Women's Substantive Representation in Pakistan: a Study in Socio Political Constraints on Policymaking

REGIME TYPE AND WOMEN’S SUBSTANTIVE REPRESENTATION IN PAKISTAN: A STUDY IN SOCIO POLITICAL CONSTRAINTS ON POLICYMAKING PhD DISSERTATION Submitted by Naila Maqsood Reg. No. NDU-GPP/Ph.D-009/F-002 Supervisor Dr. Sarfraz Hussain Ansari Department of Government & Public Policy Faculty of Contemporary Studies National Defence University Islamabad 2016 REGIME TYPE AND WOMEN’S SUBSTANTIVE REPRESENTATION IN PAKISTAN: A STUDY IN SOCIO POLITICAL CONSTRAINTS ON POLICY MAKING PhD DISSERTATION Submitted by Naila Maqsood Reg. No. NDU-GPP/Ph.D-009/F-002 This Dissertation is submitted to National Defence University, Islamabad in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government and Public Policy Supervisor Dr. Sarfraz Hussain Ansari Department of Government & Public Policy Faculty of Contemporary Studies National Defence University Islamabad 2016 Certificate of Completion It is hereby recommended that the dissertation submitted by Ms. Naila Maqsood titled “Regime Type and Women’s Substantive Representation in Pakistan: A Study in Socio-Political Constraints on Policymaking” has been accepted in the partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in the discipline of Government & Public Policy. __________________________________ Supervisor __________________________________ External Examiner Countersigned By: …………………………………………… …………………………………….. Controller Examination Head of department Supervisor’s Declaration This is to certify that PhD dissertation submitted by Ms. Naila Maqsood titled “Regime Type and Women’s Substantive Representation in Pakistan: A Study in Socio-Political Constraints on Policymaking” is supervised by me, and is submitted to meet the requirements of PhD degree. Date: _____________ Dr. Sarfraz Hussain Ansari Supervisor Scholar’s Declaration I hereby declare that the thesis submitted by me titled “Regime Type and Women’s Substantive Representation in Pakistan: A Study in Socio- Political Constraints on Policymaking” is based on my own research work and has not been submitted to any other institution for any other degree. -

“Dreams Turned Into Nightmares” Attacks on Students, Teachers, and Schools in Pakistan WATCH

H U M A N R I G H T S “Dreams Turned into Nightmares” Attacks on Students, Teachers, and Schools in Pakistan WATCH “Dreams Turned into Nightmares” Attacks on Students, Teachers, and Schools in Pakistan Copyright © 2017 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-34518 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org MARCH 2017 ISBN: 978-1-6231-34518 “Dreams Turned into Nightmares” Attacks on Students, Teachers, and Schools in Pakistan Map .................................................................................................................................... I Glossary ............................................................................................................................. II Summary ..........................................................................................................................