Is Makeup a Sin?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalog So Beyond

SO BEYOND CATALOG FLAWLESS, BEAUTIFUL true to you / no imitations / beauty is a lifestyle YOUR BEAUTY INSPIRES US. YOUR PERSONALITY AND THE WAY YOU EXPRESS YOURSELF DRIVES US TO CREATE MAKEUP JUST FOR YOU. WE ARE ALWAYS SEEKING THE PERFECT SHADE COMBINATION, TESTING NEW AND BETTER FORMULAS AND CREATING TOOLS TO HELP YOU TRANSFORM YOUR LOOK WITH EASE. ALONG WITH OUR TIME-TESTED FAVORITES, WE ARE EXCITED TO SHARE SOME GREAT NEW PRODUCTS THAT WE HOPE YOU WILL LOVE AS MUCH AS WE DO. ALWAYS, STAY TRUE TO YOU. SKIN TINT CRÈME CC CRÈME Luxurious, medium-coverage Designed to hydrate, control oil, foundation delivers moisture and and create a full-coverage finish. PERFECTING hydration with a water-gel Formulated with skin-loving POWDER INVINCIBLE formula that glides on and dries ingredients to perfect and renew ANTI-AGING quickly to achieve a silky, the appearance of skin. Vitamin Translucent, loose setting HD FOUNDATION luminescent finish. It works to E beads burst on skin during powder increases foundation minimize the appearance of fine application creating a luxurious wear while perfecting the Full-coverage foundation lines and wrinkles while feel and creamy consistency that appearance of the skin. Applies improves the appearance of fine providing a light-feeling, natural is easy to blend to a natural smoothly to set makeup without lines, skin tone, and pores. finish that is perfect for even the finish. adding any weight. This setting Moisture-rich formula hydrates most sensitive of skin. Oil free. powder is ideal for all skin types skin for a flawless demi-matte *PACKAGING MAY VARY DUE TO REBRAND. -

Makeup Catalog Contents

2020 MAKEUP CATALOG CONTENTS 1 MediaPRO® Sheer Foundations 9 Eye Shadows + Palettes 15 Eye Liners & Mascara Poudre Compacts + Palettes 10 Pearl Sheen Shadows + Palettes Eyebrow & Eye Liner Pencils 2 MatteHD Foundations + Palettes Golden Glam Palette 16 Lipsticks & Lip Pencils Studio Color MatteHD Palettes Rio Nights Palette Lip Palettes, Colors + Gloss 3 Divine Madness Palette 17 ProColor Airbrush Foundations, 18 MagiCake® & MagiCakeFX Contours & Concealers 11 Lumière Grande Colour + Palettes Death Color Cakes Luxe & UltraLuxe Powders 4 Color Cake Foundations 19 Primary & Pro Creme Colors Creme Foundations 12 Lumière Metallics Master Creme Palette 5 Studio Color Contour Palettes Luxe Sparkle Powders Clown White & Clown White Lite Creme Rouge, Highlights Sparklers & Aqua Glitters MagiColor Pencils & Crayons Glitter Glue & Glitz-It Gel & Shadows + Wheels FX Creme Colors + Palettes Lumière Cremes + Palettes 20 MediaPRO Concealers & Adjusters 13 Creme Death Foundations 6 Fireworks + Wheel 7 Concealer Palettes & Crayons Shimmer Crayons 21 Pro FX Wheels Alcohol Tattoo Cover & Heavy Metal Alcohol Palette ProColor Airbrush Paint Concealer Palettes 22 14 Luxury Powders Grime FX Quick Liquids Powder Blush + Palettes 8 Classic Powders 23 Grime FX Powders Shimmer Powders Alcohol FX Palettes 24 Sealers, Cleansers & Removers 25 Hair Colors & Crepe Wool Hair Tooth Colors & Bronzing Tint 26 Blood & Character Effects Front Cover Latex & Nose Wax Makeup Artists 27 (Clockwise from top L): Adhesives & Glitter Glue “Abstract Art” 28 Tools & Applicators Stan Edmonds 29 Professional Brushes “Ogre” Darren Jinks 32 Theatrical Creme Kits Turandot’s “Ice Princess” Personal Creme Kits Tiiu Luht 33 Cake Kit “Vision” Master Production Kit Lianne Mosley “Djinn” BACK COVER Darren Jinks Moulage Kits “Peonies” Nelly Rechia, Makeup Artist Assisted by Andrew Velazquez During a visit to Ben Nye, Nelly Rechia and Andrew Velazquez chose their must-have Powder Blush shades which evolved into our redesigned Studio Color Blush Palettes. -

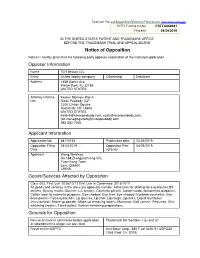

Notice of Opposition Opposer Information Applicant Information

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA969381 Filing date: 04/24/2019 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Notice of Opposition Notice is hereby given that the following party opposes registration of the indicated application. Opposer Information Name TLH Beauty LLC Entity limited liability company Citizenship Delaware Address 1458 Aloma Ave. Winter Park, FL 32789 UNITED STATES Attorney informa- Kristen Mollnow Walsh tion Nixon Peabody LLP 1300 Clinton Square Rochester, NY 14604 UNITED STATES [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 585-263-1065 Applicant Information Application No 88170154 Publication date 03/26/2019 Opposition Filing 04/24/2019 Opposition Peri- 04/25/2019 Date od Ends Applicant Wang Weichao No.188,Zhengjiazhuang Vill., Yuanshang Town, Laixi, 266600 CHINA Goods/Services Affected by Opposition Class 003. First Use: 2016/10/11 First Use In Commerce: 2016/10/11 All goods and services in the class are opposed, namely: Adhesives for affixing false eyelashes;BB creams; Beauty masks; Blusher; CC creams; Cosmetic pencils; Cotton swabs forcosmetic purposes; Cotton wool for cosmetic purposes; Eye-shadow; Eye liner; Eye shadow; Eyebrow cosmetics; Eye- brow pencils; False eyelashes; Lip glosses; Lip liner; Lip rouge; Lipsticks; Liquid foundation (mizu-oshiroi); Make-up powder; Make-up removing lotions; Mascaras; Nail varnish; Perfumes; Skin whitening creams; Toilet waters; Varnish-removing preparations Grounds for Opposition No use of mark in commerce before application Trademark Act Sections 1(a) and (c) or amendment to allege use was filed Fraud on the USPTO In re Bose Corp., 580 F.3d 1240, 91 USPQ2d 1938 (Fed. -

Cosmetics in Roman Antiquity: Substance, Remedy, Poison Author(S): KELLY OLSON Source: the Classical World, Vol

Cosmetics in Roman Antiquity: Substance, Remedy, Poison Author(s): KELLY OLSON Source: The Classical World, Vol. 102, No. 3 (SPRING 2009), pp. 291-310 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press on behalf of the Classical Association of the Atlantic States Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40599851 Accessed: 28-06-2016 17:54 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40599851?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Classical Association of the Atlantic States are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Classical World This content downloaded from 141.211.4.224 on Tue, 28 Jun 2016 17:54:40 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Cosmetics in Roman Antiquity: Substance, Remedy, Poison ABSTRACT: Mention of ancient makeup, allusions to its associations, and its connection to female beauty are scattered throughout Latin literature. It may seem a minor, even unimportant concern, but nonetheless one from which we may recover aspects of women s historical experience and knowledge of women as cultural actors. -

Toxic Elements in Traditional Kohl-Based Eye Cosmetics in Spanish and German Markets

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Toxic Elements in Traditional Kohl-Based Eye Cosmetics in Spanish and German Markets Elisabet Navarro-Tapia 1,2,3,† , Mariona Serra-Delgado 3,4,†, Lucía Fernández-López 5, Montserrat Meseguer-Gilabert 5, María Falcón 5, Giorgia Sebastiani 1,6, Sebastian Sailer 1,6, Oscar Garcia-Algar 1,3,6,‡ and Vicente Andreu-Fernández 1,2,*,‡ 1 Grup de Recerca Infancia i Entorn (GRIE), Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), 08036 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] (E.N.-T.); [email protected] (G.S.); [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (O.G.-A.) 2 Department of Health, Valencian International University (VIU), 46002 Valencia, Spain 3 Maternal & Child Health and Development Research Network-Red SAMID Health Research, Programa RETICS, Health Research Institute Carlos III, 28029 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] 4 Institut de Recerca Sant Joan de Déu, 08950 Esplugues de Llobregat, Spain 5 Departamento de Ciencias Sociosanitarias, Medicina Legal y Forense, Universidad de Murcia, 30003 Murcia, Spain; [email protected] (L.F.-L.); [email protected] (M.M.-G.); [email protected] (M.F.) 6 Department of Neonatology, Hospital Clínic-Maternitat, ICGON, Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Barcelona Center for Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine (BCNatal), 08036 Barcelona, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors share co-first authorship. ‡ These authors share last authorship. Citation: Navarro-Tapia, E.; Serra-Delgado, M.; Fernández-López, Abstract: Kohl is a traditional cosmetic widely used in Asia and Africa. In recent years, demand L.; Meseguer-Gilabert, M.; Falcón, M.; for kohl-based eyelids and lipsticks has increased in Europe, linked to migratory phenomena of Sebastiani, G.; Sailer, S.; Garcia-Algar, populations from these continents. -

Marr, Kathryn Masters Thesis.Pdf (4.212Mb)

MIRRORS OF MODERNITY, REPOSITORIES OF TRADITION: CONCEPTIONS OF JAPANESE FEMININE BEAUTY FROM THE SEVENTEENTH TO THE EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Japanese at the University of Canterbury by Kathryn Rebecca Marr University of Canterbury 2015 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ·········································································· 1 Abstract ························································································· 2 Notes to the Text ·············································································· 3 List of Images·················································································· 4 Introduction ···················································································· 10 Literature Review ······································································ 13 Chapter One Tokugawa Period Conceptions of Japanese Feminine Beauty ························· 18 Eyes ······················································································ 20 Eyebrows ················································································ 23 Nose ······················································································ 26 Mouth ···················································································· 28 Skin ······················································································· 34 Physique ················································································· -

COSMETICS in USE: a PHARMACOLOGICAL REVIEW Abdul Kader Mohiuddin, Department of Pharmacy, World University of Bangladesh KEYWORD

European Journal of Biology and Medical Science Research Vol.7, No.4, pp.22-64, October 2019 Published by ECRTD- UK Print ISSN: ISSN 2053-406X, Online ISSN: ISSN 2053-4078 COSMETICS IN USE: A PHARMACOLOGICAL REVIEW Abdul Kader Mohiuddin, Department of Pharmacy, World University of Bangladesh 151/8, Green Road, Dhanmondi, Dhaka – 1205, Bangladesh Orcid Id: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1596-9757 Web of Science Researcher ID: T-5428-2019 ABSTRACT: The word “cosmetics” actually stems from its use in Ancient Rome. They were typically produced by female slaves known as “cosmetae,” which is where the word “cosmetics” stemmed from. Cosmetics are used to enhance appearance. Makeup has been around for many centuries. The first known people who used cosmetics to enhance their beauty were the Egyptians. Makeup those days was just simple eye coloring or some material for the body. Now-a-days makeup plays an important role for both men and women. In evolutionary psychology, social competition of appearance strengthens women’s desires for ideal beauty. According to “The Origin of Species”, humans have evolved to transfer genes to future generations through sexual selection that regards the body condition of ideal beauty as excellent fertility. Additionally, since women’s beauty has recently been considered a competitive advantage to create social power, a body that meets the social standards of a culture could achieve limited social resources. That's right, even men have become more beauty conscious and are concerned about their looks. Cosmetics can be produced in the organic and hypoallergenic form to meet the demands of users. -

Title Semiotics of the Other and Physical Beauty: the Cosmetics Industry and the Transformation of Ideals of Beauty in the U.S

Semiotics of the Other and Physical Beauty: The Cosmetics Title Industry and the Transformation of Ideals of Beauty in the U.S. and Japan, 1800's - 1960's Author(s) Isa, Masako 沖縄大学人文学部紀要 = Journal of the Faculty of Citation Humanities and Social Sciences(4): 31-48 Issue Date 2003-03-31 URL http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12001/6070 Rights 沖縄大学人文学部 2003 Semiotics of the Other and Physical Beauty: The Cosmetics Industry and the Transformation of Ideals of Beauty in the U.S. and Japan, 1800's - 1960's Masako Isa Abstract This paper describes theoretical aspects of the "Other" by Jacques Lacan and examines the historical development of ideals of physical beauty in the United States and Japan. The Lacan's concept of the "Other" in relation to a technology for creating the appearance of the Other in the beauty industry is investigated. Cosmetic industry tries to create the appearance of the Other by using the technology of cosmetics and discourse of ads. In the U.S., beauty culture, motion pictures, the establishment of the African-American segment of the industry, and immigration from other countries have influenced the cultural construction of beauty. In Japan, the modern cosmetics industry, motion pictures, and foreign manufacturers contributed to the transformation of ideals of physical beauty. Through examining cultural events of the cosmetic industry in both countries, it is concluded that beauty is not universal, but is culturally constructed by society. What is common between both countries is influence from the outside. Keywords: semiotics, the "Other", unconscious, mirror stage, cosmetics industry I. -

Youngblood® M Ineral Cosmetics

PRODUCT INFORMATION WORKBOOK YOUNGBLOOD® M INERAL COSMETICS 4583 Ish Drive • Simi Valley, CA 93063 800 216 6133 • YBSKIN.COM TABLE OF CONTENTS 2. PAULINE’S STORY • 3 KEY POINTS • YB DIFFERENCE PRODUCTS PREP 4. MINERALS IN THE MIST TM 5. EYE IMPACT QUICK RECOVERY EYE CREAM PRIMERS 6. MINERAL PRIMER 7. ANTI-SHINE MATTIFIER 8. CC PRIMER, STAY PUT EYE PRIME, BREAK AWAY MAKEUP REMOVER ESSENTIALS 9. COUNTOUR & ILLUMINATE PALETTES 10. ULTIMATE CONCEALER/ULTIMATE CORRECTOR 11. MINERAL RICE POWDER 12. HI-DEFINITION HYDRATING MINERAL PERFECTING POWDER FOUNDATIONS 13. SHADE CHART 14. STEPS TO MATCH FOUNDATION 15. LOOSE MINERAL FOUNDATION 16. PRESSED MINERAL FOUNDATION 17. MINERAL RADIANCE CRÈME POWDER FOUNDATION 18. MINERAL RADIANCE MOISTURE TINT 19. LIQUID MINERAL FOUNDATION 20. TROUBLE SHOOTING APPLICATION TIPS 21. COLOR WHEEL CHEEKS 22. MINERAL RADIANCE 23. PRESSED MINERAL BLUSH 24. LOOSE MINERAL BLUSH 25. LUMINOUS CRÈME BLUSH EYES 26. BROW ARTISTE KIT & WAX 27. BROW ARTISTE SCULPTING PENCIL 28. EYE-LLUMINATING DUO 29. PRESSED INDIVIDUAL EYESHADOW 30. PRESSED MINERAL EYESHADOW QUAD 31. EYE LINER PENCIL 32. INCREDIBLE WEAR GEL LINER 33. EYE-MAZING LIQUID LINER PEN 34. OUTRAGEOUS LASHES MINERAL LENGTHENING MASCARA 35. NOTES LIPS 36. LIPSTICK 37. LIP LINER PENCIL 38. LIP GLOSS 39. HYDRATING LIP CRÈME SPF 15 BROAD SPECTRUM BODY 40. LUNAR DUST 41. MINERAL ILLUMINATING TINT BODY 42-43. NOTES TIPS & TEQHNIQUES 44. GET THE LOOK 45-46. THE YOUNGBLOOD EXPERIENCE 47-48. FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS 49. NOTES INGREDIENTS UNIVERSAL INGREDIENT LISTINGS FOR ALL PRODUCTS PARABEN FREE • TALC FREE • • FRAGRANCE FREE V SELECT VEGAN PRODUCTS SELECT GLUTEN FREE PRODUCTS 3-2017 Granting women the power to conceal and correct imperfect complexions has been the mission of Pauline Youngblood, founder and president of Youngblood Mineral Cosmetics. -

Determination of Lead and Cadmium in Cosmetic Products

Available on line www.jocpr.com Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research __________________________________________________ J. Chem. Pharm. Res., 2010, 2(6):92-97 ISSN No: 0975-7384 CODEN(USA): JCPRC5 Determination of Lead and Cadmium in cosmetic products Amit S Chauhan 1* , Rekha Bhadauria 1, Atul K Singh 2, Sharad S Lodhi 3, Dinesh K Chaturvedi 1, Vinayak S Tomar 1 1School of Studies in Botany, Jiwaji University, Gwalior (M.P.), India. 2Department of Biotechnology, Madhav Institute of Technology & Science Gwalior (M.P.), India 3School of Studies in Biochemistry, Jiwaji University Gwalior (M.P.), India _____________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT Heavy metal toxicity to the humans and animals is the result of long term low or high level exposure to pollutants common in our environment including in air we breathe, water, food etc. Apart from these, numerous consumer products like cosmetics and toiletries have been reported as a source of heavy metal exposure to human beings. Heavy metals like lead and cadmium were determined in different cosmetics products viz soap, face cream, shampoo, shaving cream etc from local market of Gwalior with atomic absorption spectrophotometer. Lead was prominently detected in all of cosmetics products followed by cadmium. Among the different cosmetics products studied, the highest heavy metal contamination was found in bathing soap. Present study concludes that though in less amount but beauty cosmetic products are contaminate with heavy metals and hence may results in skin problems. Key words: Lead, cadmium, cosmetic products. ______________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION Since the dawn of civilization cosmetics have constituted a part of routine body care not only by the upper strata of society but also by middle and low class people. -

Dior Cosmetics, Fragrances & More Ingredients List

Dior Cosmetics, Fragrances & More Ingredients List 1 Synthetic fluorphlogopite, talc, boron nitriqe, barium sulfate, diphenyl dimethiconeninyl diphenyl dimethicone/silsesquioxane crosspolymer, nylon-12, octylex)decyl stearoyl stearate, magnesium myristate, phenyl trimethicone, acrylates/stbnftyl acrylate/dimeihicone methacrylate copolymer, calcium aluminum borosilicate, pentylene glycol, hdi/trimethylcl hexyllactone crosspolymer, dimethicone, lauroyl lysine, sodium dehydroacetate, silica, hydrogen dimethicone, tin oxide, palmitic acid, magnesium hydroxide n 09384/a. 2 Synthetic fluorphlogopite, dimethicone, talc, diisostearyl malate, methyl methacrylate crosspolymer, petrolatum, mica, trimethylolpropane triethylhexanoate, magnesium myristate, hdi/ppg/ polycaprolactone crosspolymer, sorbitan sesquiisostearate, siuca, trimethylsiloxysilicate, polypropyl, silsesqumane, sodium dehydroacetate, sorbic acid, ethylhexylglycerin, glyceryl caprylate, tocopherol n 09458/a. 3 Dimethicone, mica, talc, diisostearyl malate, synthetic fluorphlogopite, methyl methacrylate crosspolymer, petrolatum, trimethylolpropane triethylhexanoate, magnesium myristate, hdi/ppg/ polycaprolactone crosspolymer, silica, sorbitan sesquiisostearate, trimethylsiloxysilicate, polypropyl- silsesquioxane, sodium dehydroacetate, sorbic acid, lauroyl lysine, ethylhexylglycerin, glyceryl caprylate, tin oxide, tocopherol, n 09451/a. 5 Color Designer All In One Artistry Palette - 4 Dimethicone, talc, calcium sodium borosilicate, silica, No. 208 Navy Design diisostearyl malate, petrolatum, -

Dec. 25, 1956 2,775,247

Dec. 25, 1956 J. C. MORREL 2,775,247 COSMETIC PACKAGE Filed April 13, 1951 2,775,247 United States Patent Office Patented Dec. 25, 1956 2 1 in Figures 1, 2 and 3 consists of a base 2 made of card board or a relatively thin sheet of other fibrous material, plastic or the like, with open cell or trough-like depres 2,775,247 sion 3 containing cosmetic 4. There may be one or more cells containing cosmetics. The cosmetics may COSMETEC PACKAGE comprise face powder, lip rouge, rouge and the like. Jacque C. Morrell, Chevy Chase, Md. The face powder may be in the form of a cake as shown in these figures which may be held in place by adhesives Application April 13, 1951, Serial No. 220,936 or the face powder may be loose in the cell and kept in 10 place by a cover of paper, cellophane, etc., by the use 6 Claims. (Cl. 132-79) of adhesives or by "Scotch' tape or the like, not shown in Figures 1, 2 and 3, but shown in Figure 4; and ap plicable to the other figures. An oil-impervious sheet 6 such as cellulosic material, e. g., of the regenerated This invention relates to cosmetic packages particu 5 cellulose type or plastic or the like, covers the top Sur larly packages of a compact and inexpensive type adapted faces of the base 2 and the open cell or depression 3 for dispensing or marketing through automatic, coin and the cosmetics and more particularly when the pack operated vending machines, and is a continuation-in-part age is closed may serve as a protector for the plurality of my application Serial No.