Dolley-Madison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Custom Book List (Page 2)

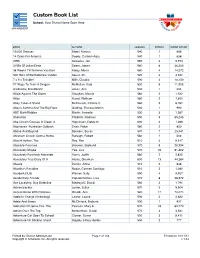

Custom Book List School: Your District Name Goes Here MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® POINTS WORD COUNT 10,000 Dresses Ewert, Marcus 540 1 688 14 Cows For America Deedy, Carmen Agra 540 1 638 2095 Scieszka, Jon 590 3 9,974 3 NBs Of Julian Drew Deem, James 560 6 36,224 38 Weeks Till Summer Vacation Kerby, Mona 580 4 14,272 500 Hats Of Bartholomew Cubbin Seuss, Dr. 520 3 3,941 7 x 9 = Trouble! Mills, Claudia 590 4 10,150 97 Ways To Train A Dragon McMullan, Kate 520 5 11,905 Aardvarks, Disembark! Jonas, Ann 530 1 334 Abbie Against The Storm Vaughan, Marcia 560 2 1,933 Abby Hanel, Wolfram 580 2 1,853 Abby Takes A Stand McKissack, Patricia C. 580 5 8,781 Abby's Asthma And The Big Race Golding, Theresa Martin 530 1 990 ABC Math Riddles Martin, Jannelle 530 3 1,287 Abduction Philbrick, Rodman 590 9 55,243 Abe Lincoln Crosses A Creek: A Hopkinson, Deborah 600 3 1,288 Aborigines -Australian Outback Doak, Robin 580 2 850 Above And Beyond Bonners, Susan 570 7 25,341 Abraham Lincoln Comes Home Burleigh, Robert 560 1 508 Absent Author, The Roy, Ron 510 3 8,517 Absolute Pressure Brouwer, Sigmund 570 8 20,994 Absolutely Maybe Yee, Lisa 570 16 61,482 Absolutely Positively Alexande Viorst, Judith 580 2 2,835 Absolutely True Diary Of A Alexie, Sherman 600 13 44,264 Abuela Dorros, Arthur 510 2 646 Abuelita's Paradise Nodar, Carmen Santiago 510 2 1,080 Accidental Lily Warner, Sally 590 4 9,927 Accidentally Friends Papademetriou, Lisa 570 8 28,972 Ace Lacewing: Bug Detective Biedrzycki, David 560 3 1,791 Ackamarackus Lester, Julius 570 3 5,504 Acquaintance With Darkness Rinaldi, Ann 520 17 72,073 Addie In Charge (Anthology) Lawlor, Laurie 590 2 2,622 Adele And Simon McClintock, Barbara 550 1 837 Adoration Of Jenna Fox, The Pearson, Mary E. -

GOVPUB-CS1-4C9e09d16748d10e2bdd184198d2c071-1.Pdf

I 1 Proi Of RECORDS, [NISTRATION f 4&**i /$ Tio,r «c0iSrte^u REGISTER OF ALL OFFICERS AND AGENTS, CIVIL, MILITARY, AND NAVAL, IN SERVICETHE OF THE UNITED STATES, ON The Thirtieth September, 1851. WITH THE NAMES, FORCER AND CONDITION OP ALL SHIPS AND VESSELS BELONG-- ING TO THE UNITED STATES, AND WHEN AND WHERE BUILT ; TOGETHER WITH THE NAMES AND COMPENSATION OF ALL PRINTERS IN ANY WAX EMPLOYED BY CONGRESS, OB ANY DEPARTMENT OR OFFICER OF THE GOVERNMENT. PREPARED AT THE DEPARTMENT OF STATE, In pursuance of Resolutions of Congress of April 27,1816, and July 14,1832. WASHINGTON: GIDEON AND CO., PRINTERS. 1851. RESOLUTION requiring the Secretary of State to compile and print, once in every two years, a register of all officers and agents, civil, military, and naval, in the service ot tne United States. Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Con gress assembled, That, once in two years, a Register, containing correct lists of all the officers and agents, civil, military, and naval, in the service of the United States, made up to the last day of September of each year in which a new Congress is to assemble, be compiled and printed, under the direction of the Secretary for the Department of State. And, to ena ble him to form such Register, he, for his own Department, and the Heads of the other De partments, respectively, shall, in due time, cause such lists as aforesaid, of all officers and agents, in their respective Departments, including clerks, cadets, and midshipmen, to be made and lodged in the office of the Department of State. -

1985 Commencement Program, University Archives, University Of

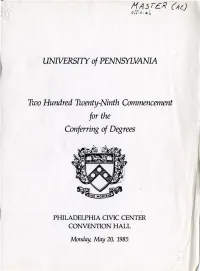

UNIVERSITY of PENNSYLVANIA Two Hundred Twenty-Ninth Commencement for the Conferring of Degrees PHILADELPHIA CIVIC CENTER CONVENTION HALL Monday, May 20, 1985 Guests will find this diagram helpful in locating the Contents on the opposite page under Degrees in approximate seating of the degree candidates. The Course. Reference to the paragraph on page seven seating roughly corresponds to the order by school describing the colors of the candidates' hoods ac- in which the candidates for degrees are presented, cording to their fields of study may further assist beginning at top left with the College of Arts and guests in placing the locations of the various Sciences. The actual sequence is shown in the schools. Contents Page Seating Diagram of the Graduating Students 2 The Commencement Ceremony 4 Commencement Notes 6 Degrees in Course 8 • The College of Arts and Sciences 8 The College of General Studies 16 The School of Engineering and Applied Science 17 The Wharton School 25 The Wharton Evening School 29 The Wharton Graduate Division 31 The School of Nursing 35 The School of Medicine 38 v The Law School 39 3 The Graduate School of Fine Arts 41 ,/ The School of Dental Medicine 44 The School of Veterinary Medicine 45 • The Graduate School of Education 46 The School of Social Work 48 The Annenberg School of Communications 49 3The Graduate Faculties 49 Certificates 55 General Honors Program 55 Dental Hygiene 55 Advanced Dental Education 55 Social Work 56 Education 56 Fine Arts 56 Commissions 57 Army 57 Navy 57 Principal Undergraduate Academic Honor Societies 58 Faculty Honors 60 Prizes and Awards 64 Class of 1935 70 Events Following Commencement 71 The Commencement Marshals 72 Academic Honors Insert The Commencement Ceremony MUSIC Valley Forge Military Academy and Junior College Regimental Band DALE G. -

Ten Years in Washington. Life and Scenes in the National Capital, As a Woman Sees Them

Library of Congress Ten years in Washington. Life and scenes in the National Capital, as a woman sees them Mary Clemmer Ames TEN YEARS IN WASHINGTON. LIFE AND SCENES IN THE NATIONAL CAPITAL, AS A WOMAN SEES THEM. 486 642 BY MARY CLEMMER AMES, Author of “Eirene, or a Woman's Right,” “Memorials of Alice and Phœbe Cary,” “A Woman's Letters from Washington,” “Outlines of Men, Women and Things,” etc. FULLY ILLUSTRATED WITH THIRTY FINE ENGRAVINGS, AND A PORTRAIT OF THE AUTHOR ON STEEL. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON COPYRIGHT 1873 No 57802 HARTFORD, CONN.: A. D. WORTHINGTON & CO. M. A. PARKER & CO., Chicago, Ills. F. DEWING & CO., San Francisco, Cal. 1873. no. 2 F1?8 ?51 Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1873, by A. D. WORTHINGTON & CO., In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. Case Lockwood & Brainard, PRINTERS AND BINDERS, Cor. Pearl and Trumbull Sts., Hartford, Conn. Ten years in Washington. Life and scenes in the National Capital, as a woman sees them http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbcb.28043 Library of Congress I wish to acknowledge my indebtedness, in gathering the materials of this book, to Mr. A. R. Spofford, Librarian of Congress; to Col. F. Howe; to the Chiefs of the several Government Bureaus herein described; to Mr. Colbert Lanston of the Bureau of Pensions; to Mr. Phillips, of the Bureau of Patents; and to Miss Austine Snead. M. C. A. TO Mrs. HAMILTON FISH, TO Mrs. ROSCOE CONKLING, OF NEW YORK, TWO LADIES, WHO, IN THE WORLD, ARE YET ABOVE IT,—WHO USE IT AS NOT ABUSING IT, WHO EMBELLISH LIFE WITH THE PURE GRACES OF CHRISTIAN WOMANHOOD, THESE SKETCHES OF OUR NATIONAL CAPITAL ARE SINCERELY Dedicated BY MARY CLEMMER AMES. -

Social Life in the Early Republic: a Machine-Readable Transcription

Library of Congress Social life in the early republic vii PREFACE peared to them, or recall the quaint figures of Mrs. Alexander Hamilton and Mrs. Madison in old age, or the younger faces of Cora Livingston, Adèle Cutts, Mrs. Gardiner G. Howland, and Madame de Potestad. To those who have aided her with personal recollections or valuable family papers and letters the author makes grateful acknowledgment, her thanks being especially due to Mrs. Samuel Phillips Lee, Mrs. Beverly Kennon, Mrs. M. E. Donelson Wilcox, Miss Virginia Mason, Mr. James Nourse and the Misses Nourse of the Highlands, to Mrs. Robert K. Stone, Miss Fanny Lee Jones, Mrs. Semple, Mrs. Julia F. Snow, Mr. J. Henley Smith, Mrs. Thompson H. Alexander, Miss Rosa Mordecai, Mrs. Harriot Stoddert Turner, Miss Caroline Miller, Mrs. T. Skipwith Coles, Dr. James Dudley Morgan, and Mr. Charles Washington Coleman. A. H. W. Philadelphia, October, 1902. ix CONTENTS Chapter Page I— A Social Evolution 13 II— A Predestined Capital 42 Social life in the early republic http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbcb.29033 Library of Congress III— Homes and Hostelries 58 IV— County Families 78 V— Jeffersonian Simplicity 102 VI— A Queen of Hearts 131 VII— The Bladensburg Races 161 VII— Peace and Plenty 179 IX— Classics and Cotillions 208 X— A Ladies' Battle 236 XI— Through Several Administrations 267 XII— Mid-Century Gayeties 296 xi ILLUSTRATIONS Page Mrs. Richard Gittings, of Baltimore (Polly Sterett) Frontispiece From portrait by Charles Willson Peale, owned by her great-grandson, Mr. D. Sterett Gittings, of Baltimore. Mrs. Gittings eyes are dark brown, the hair dark brown, with lighter shades through it; the gown of delicate pink, the sleeves caught up with pearls, the sash of a gray shade. -

Philadelphia and the Southern Elite: Class, Kinship, and Culture in Antebellum America

PHILADELPHIA AND THE SOUTHERN ELITE: CLASS, KINSHIP, AND CULTURE IN ANTEBELLUM AMERICA BY DANIEL KILBRIDE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1997 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In seeing this dissertation to completion I have accumulated a host of debts and obligation it is now my privilege to acknowledge. In Philadelphia I must thank the staff of the American Philosophical Society library for patiently walking out box after box of Society archives and miscellaneous manuscripts. In particular I must thank Beth Carroll- Horrocks and Rita Dockery in the manuscript room. Roy Goodman in the Library’s reference room provided invaluable assistance in tracking down secondary material and biographical information. Roy is also a matchless authority on college football nicknames. From the Society’s historian, Whitfield Bell, Jr., I received encouragement, suggestions, and great leads. At the Library Company of Philadelphia, Jim Green and Phil Lapansky deserve special thanks for the suggestions and support. Most of the research for this study took place in southern archives where the region’s traditions of hospitality still live on. The staff of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History provided cheerful assistance in my first stages of manuscript research. The staffs of the Filson Club Historical Library in Louisville and the Special Collections room at the Medical College of Virginia in Richmond were also accommodating. Special thanks go out to the men and women at the three repositories at which the bulk of my research was conducted: the Special Collections Library at Duke University, the Southern Historical Collection of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and the Virginia Historical Society. -

National Register of Historic Places

Form No. ^0-306 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Independence National Historical Park AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 313 Walnut Street CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT t Philadelphia __ VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE PA 19106 CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE ^DISTRICT —PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE 2LMUSEUM -BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE X-UNOCCUPIED —^COMMERCIAL 2LPARK .STRUCTURE 2EBOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —XEDUCATIONAL ^.PRIVATE RESIDENCE -SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS -OBJECT —IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED ^GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: REGIONAL HEADQUABIER REGION STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE PHILA.,PA 19106 VICINITY OF COURTHOUSE, ____________PhiladelphiaREGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. _, . - , - , Ctffv.^ Hall- - STREET & NUMBER n^ MayTftat" CITY. TOWN STATE Philadelphia, PA 19107 TITLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL CITY. TOWN CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED 2S.ORIGINALSITE _GOOD h^b Jk* SANWJIt's ALTERED _MOVED DATE. —FAIR _UNEXPOSED Description: In June 1948, with passage of Public Law 795, Independence National Historical Park was established to preserve certain historic resources "of outstanding national significance associated with the American Revolution and the founding and growth of the United States." The Park's 39.53 acres of urban property lie in Philadelphia, the fourth largest city in the country. All but .73 acres of the park lie in downtown Phila-* delphia, within or near the Society Hill and Old City Historic Districts (National Register entries as of June 23, 1971, and May 5, 1972, respectively). -

Dolley Madison

Life Story Dolley Madison 1768–1849 expulsion from Quaker Meeting, and his wife took in boarders to make ends meet . Perhaps pressured by her father, who died shortly after, Dolley, at 22, married Quaker lawyer John Todd, whom she had once rejected . Her 11-year- old sister, Anna, lived with them . The Todds’ first son, called Payne, was born in 1791, and a second son, William, followed in 1793 . In the late summer of that year, yellow fever hit Philadelphia, and before cold weather ended the epidemic, Dolley lost four members of her family: her father-in-law, her mother-in-law, and then, on the same October day, her husband and three-month-old William . She wrote a half-finished sentence in a letter: “I am now so unwell that I can’t . ”. James Sharples Sr ., Dolley Madison, ca . 1796–1797 . Pastel on paper . Independence National Historic Park, Philadelphia . Added to her grief, Dolley faced an financial strain at the same time . Fifty extremely difficult situation . She was years later, she would face them again . a widow caring for her small son and her young sister . Men were considered Dolley’s mother went to live with a responsible for their female relatives; it was married daughter, and Dolley, Payne, one of the social side effects of coverture and Anna moved back to the family (see Resource 1) . But all the men who might home . Philadelphia was then the nation’s have cared for Dolley were gone . Her temporary capital and most sophisticated husband had left her some money in his city . -

9/11 Report”), July 2, 2004, Pp

Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page i THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— ...in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page vi 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

Executive Order 13978 of January 18, 2021

6809 Federal Register Presidential Documents Vol. 86, No. 13 Friday, January 22, 2021 Title 3— Executive Order 13978 of January 18, 2021 The President Building the National Garden of American Heroes By the authority vested in me as President by the Constitution and the laws of the United States of America, it is hereby ordered as follows: Section 1. Background. In Executive Order 13934 of July 3, 2020 (Building and Rebuilding Monuments to American Heroes), I made it the policy of the United States to establish a statuary park named the National Garden of American Heroes (National Garden). To begin the process of building this new monument to our country’s greatness, I established the Interagency Task Force for Building and Rebuilding Monuments to American Heroes (Task Force) and directed its members to plan for construction of the National Garden. The Task Force has advised me it has completed the first phase of its work and is prepared to move forward. This order revises Executive Order 13934 and provides additional direction for the Task Force. Sec. 2. Purpose. The chronicles of our history show that America is a land of heroes. As I announced during my address at Mount Rushmore, the gates of a beautiful new garden will soon open to the public where the legends of America’s past will be remembered. The National Garden will be built to reflect the awesome splendor of our country’s timeless exceptionalism. It will be a place where citizens, young and old, can renew their vision of greatness and take up the challenge that I gave every American in my first address to Congress, to ‘‘[b]elieve in yourselves, believe in your future, and believe, once more, in America.’’ Across this Nation, belief in the greatness and goodness of America has come under attack in recent months and years by a dangerous anti-American extremism that seeks to dismantle our country’s history, institutions, and very identity. -

Washington, Outside and Inside. a Picture and a Narrative of the Origin, Growth, Excellencies, Abuses, Beauties, and Personages of Our Governing City

Library of Congress Washington, outside and inside. A picture and a narrative of the origin, growth, excellencies, abuses, beauties, and personages of our governing city. By Geo. Alfred Townsend 2 WASHINGTON, OUTSIDE AND INSIDE. A PICTURE AND A NARRATIVE OF THE ORIGIN, GROWTH, EXCELLENCES, ABUSES, BEAUTIES, AND PERSONAGES OF OUR GOVERNING CITY. 55/1337 BY GEO. ALFRED TOWNSEND, “GATH,” AUTHOR OF “THE NEW WORLD COMPARED WITH THE OLD,” AND WASHINGTON CORRESPONDENT OF THE CHICAGO TRIBUNE. “WE do not know of any American newspaper-English which we like better, as English, than that of Mr. Geo. Alfred Townsend. Our readers are not ignorant of Mr. Townsend's services at the Capital, where he has distinguished himself as a hater of shams and friendly to all those measures of political reform to which the better portion of the Republican party is irrevocably committed. It is, to be sure, sometimes easier to be amused by Mr. Townsend's personalities, than to apologize for them; but there is a humor and picturesqueness about them which is nothing less than poetical.”—NEW YORK NATION. JAMES BETTS & CO. HARTFORD, CONN., AND CHICAGO, ILL. S. M. BETTS & CO., CINCINNATI, OHIO. Washington, outside and inside. A picture and a narrative of the origin, growth, excellencies, abuses, beauties, and personages of our governing city. By Geo. Alfred Townsend http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbcb.28587 Library of Congress 1873. F194 Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1873, BY JAMES BETTS & CO., in the Office of the Librarian of Congress at Washington. From the NEW YORK NATION. -

Franklin Roosevelt, Frank Hague, and the Presidential Election of 1936 in New Jersey

NJS: An Interdisciplinary Journal Winter 2016 120 “A Common Interest” Franklin Roosevelt, Frank Hague, and the Presidential Election of 1936 in New Jersey By Si Sheppard DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14713/njs.v2i1.30 The Great Depression and the New Deal forged a mutually beneficial alliance between President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Mayor Frank Hague of Jersey City. Each needed the other. Hague benefited from the federal funds he was allocated by the New Deal relief agencies. Channeling this government assistance through his political machine in Jersey City enabled him to consolidate his control over Hudson County and ultimately become the dominant figure of the Democratic Party in New Jersey. In return, Hague pledged to secure New Jersey for Roosevelt in his reelection campaign. Ironically, Hague got the better of this arrangement. Roosevelt’s personal popularity would have ensured his reelection in 1936 regardless of Hague’s level of commitment. But by entrenching Hague’s authority, as the New Deal tide ebbed over the ensuing years, and elections in New Jersey became more competitive, the President became ever more dependent on the capacity of the Mayor to deliver the votes he needed. This necessitated a policy of willful indifference towards Hague’s increasingly autocratic and corrupt maladministration. New Jersey today is a loyal “Blue” state, having delivered its electoral votes to the Democratic Party’s candidate for President in every election for a generation. That was not always the case, however; when Franklin D. Roosevelt ran for reelection in 1936, New Jersey was considered a key “swing” state.