Tiron Dissolution Method Used to Remove and Characterize Inorganic Components in Solls Hideomi Kodama* and G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biotechnological Applications of the Sepiolite Interactions with Bacteria

Biotechnological applications of the sepiolite interactions with bacteria: Bacterial transformation and DNA extraction Fidel Antonio Castro-Smirnov, Olivier Pietrement, Pilar Aranda, Eric Le Cam, Eduardo Ruiz-Hitzky, Bernard Lopez To cite this version: Fidel Antonio Castro-Smirnov, Olivier Pietrement, Pilar Aranda, Eric Le Cam, Eduardo Ruiz- Hitzky, et al.. Biotechnological applications of the sepiolite interactions with bacteria: Bacte- rial transformation and DNA extraction. Applied Clay Science, Elsevier, 2020, 191, pp.105613. 10.1016/j.clay.2020.105613. hal-02565762 HAL Id: hal-02565762 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02565762 Submitted on 6 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 Biotechnological applications of the sepiolite interactions with 2 bacteria: bacterial transformation and DNA extraction 3 Fidel Antonio Castro-Smirnova,b, Olivier Piétrementc,d, Pilar Arandae, Eric Le Camc, 4 Eduardo Ruiz-Hitzkye and Bernard S. Lopeza,f*. 5 6 aCNRS UMR 8200, Institut de Cancérologie Gustave-Roussy, Université Paris Sud, 7 Université Paris-Saclay, Equipe Labellisée Ligue Contre le Cancer, 114 Rue Edouard 8 Vaillant, 94805 Villejuif, France. 9 bUniversidad de las Ciencias Informáticas, Carretera a San Antonio de los Baños, km 10 1⁄2, La Habana, 19370, Cuba 11 cCNRS UMR 8126, Institut de Cancérologie Gustave-Roussy, Université Paris Sud, 12 Université Paris-Saclay, 114 Rue Édouard Vaillant, 94805 Villejuif, France. -

Microbial Interaction with Clay Minerals and Its Environmental and Biotechnological Implications

minerals Review Microbial Interaction with Clay Minerals and Its Environmental and Biotechnological Implications Marina Fomina * and Iryna Skorochod Zabolotny Institute of Microbiology and Virology of National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Zabolotny str., 154, 03143 Kyiv, Ukraine; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 13 August 2020; Accepted: 24 September 2020; Published: 29 September 2020 Abstract: Clay minerals are very common in nature and highly reactive minerals which are typical products of the weathering of the most abundant silicate minerals on the planet. Over recent decades there has been growing appreciation that the prime involvement of clay minerals in the geochemical cycling of elements and pedosphere genesis should take into account the biogeochemical activity of microorganisms. Microbial intimate interaction with clay minerals, that has taken place on Earth’s surface in a geological time-scale, represents a complex co-evolving system which is challenging to comprehend because of fragmented information and requires coordinated efforts from both clay scientists and microbiologists. This review covers some important aspects of the interactions of clay minerals with microorganisms at the different levels of complexity, starting from organic molecules, individual and aggregated microbial cells, fungal and bacterial symbioses with photosynthetic organisms, pedosphere, up to environmental and biotechnological implications. The review attempts to systematize our current general understanding of the processes of biogeochemical transformation of clay minerals by microorganisms. This paper also highlights some microbiological and biotechnological perspectives of the practical application of clay minerals–microbes interactions not only in microbial bioremediation and biodegradation of pollutants but also in areas related to agronomy and human and animal health. -

Comparison of Phyllosilicates Observed on the Surface of Mars with Those Found in Martian Meteorites

80th Annual Meeting of the Meteoritical Society 2017 (LPI Contrib. No. 1987) 6115.pdf COMPARISON OF PHYLLOSILICATES OBSERVED ON THE SURFACE OF MARS WITH THOSE FOUND IN MARTIAN METEORITES. J. L. Bishop1, and M. A. Velbel2,3, 1SETI Institute & NASA-Ames (Mountain View, CA, USA; [email protected]), 2Michigan State University (East Lansing, MI); 3Smithsonian Institution (Washington, DC). Introduction: Phyllosilicates are an important indicator of aqueous processes on Mars and have been observed on the martian surface as well as inside martian meteorites. Here we survey the types of phyllosilicates detected at the surface of Mars and inside martian rocks in order to gain a better understanding of aqueous alteration processes taking place at Mars. Comparing the phyllosilicates observed on the surface today with those found in meteorites [1] may provide clues toward understanding which phyllosilicates formed in surface environments and which formed through subsurface processes. Martian Surface: Fe/Mg-phyllosilicates are present in numerous sites where the Noachian rocks are exposed [2]. These have been detected and characterized with the OMEGA [3] and CRISM [4] imaging spectrometers. Fe- rich smectite is the most abundant phyllosilicate on the surface of Mars [5], but a large variety of phyllosilicates and short-range-ordered (SRO) materials [6] have been observed. These include: nontronite, saponite, clinochlore, chamosite, serpentine, prehnite, talc, illite, beidelite, montmorillonite, kaolinite, halloysite, opal, hydrated silica, allophane, and imogolite. These are often observed together with iron oxides/hydroxides (FeOx), sulfates or car- bonates. Phyllosilicates and SROs have also been detected on Mars by CheMin on MSL [7]. Analyses of these data from several locations indicate the presence of trioctahedral and dioctahedral smectites and SRO phases [8, 9]. -

Suspension Polymerization of Methyl Methacrylate Stabilized Solely by Palygorskite Nano Fibers*

Chinese Journal of Polymer Science Vol. 32, No. 2, (2014), 123−129 Chinese Journal of Polymer Science © Chinese Chemical Society Institute of Chemistry, CAS Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2014 Rapid Communication Suspension Polymerization of Methyl Methacrylate Stabilized Solely by Palygorskite Nano Fibers* Bai-yu Li**, Yin-ping Wang, Xiao-bin Niu and Zai-man Liu The School of Chemical & Biological Engineering, Lanzhou Jiaotong University, Lanzhou 730070, China Abstract A kind of fibrous clay, palygorskite (PAL), was used as the sole stabilizer in suspension polymerization without the using of any other stabilizer usually used, especially polymeric stabilizers. In order to improve the compatibility with the organic monomer, PAL nano fibers were organically modified with silane coupling agent methacryloxypropyltrimethoxysilane (MPS). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy results show that the hydrolyzed MPS was attached onto PAL surface through Si―O―Si bonds formation without morphology change of PAL. At a loading amount of PAL to monomer as low as 0.36 wt%, effective stabilization could be achieved. After suspension polymerization, spherical poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) particles were obtained. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis on both the outer surface and the inner cracked surface of the spherical PMMA particles indicates that the PAL particles reside on the surface of the PMMA spheres. The densely stacked PAL together with attached silane coupling agent stabilized -

Clay Minerals

CLAY MINERALS CD. Barton United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Aiken, South Carolina, U.S.A. A.D. Karathanasis University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky, U.S.A. INTRODUCTION of soil minerals is understandable. Notwithstanding, the prevalence of silicon and oxygen in the phyllosilicate structure is logical. The SiC>4 tetrahedron is the foundation Clay minerals refers to a group of hydrous aluminosili- 2 of all silicate structures. It consists of four O ~~ ions at the cates that predominate the clay-sized (<2 |xm) fraction of apices of a regular tetrahedron coordinated to one Si4+ at soils. These minerals are similar in chemical and structural the center (Fig. 1). An interlocking array of these composition to the primary minerals that originate from tetrahedral connected at three corners in the same plane the Earth's crust; however, transformations in the by shared oxygen anions forms a hexagonal network geometric arrangement of atoms and ions within their called the tetrahedral sheet (2). When external ions bond to structures occur due to weathering. Primary minerals form the tetrahedral sheet they are coordinated to one hydroxyl at elevated temperatures and pressures, and are usually and two oxygen anion groups. An aluminum, magnesium, derived from igneous or metamorphic rocks. Inside the or iron ion typically serves as the coordinating cation and Earth these minerals are relatively stable, but transform- is surrounded by six oxygen atoms or hydroxyl groups ations may occur once exposed to the ambient conditions resulting in an eight-sided building block termed an of the Earth's surface. Although some of the most resistant octohedron (Fig. -

Allophane and Imogolite: Role in Soil Biogeochemical Processes

Clay Minerals, (2009) 44, 135–155 GEORGE BROWN LECTURE 2008 Allophane and imogolite: role in soil biogeochemical processes R. L. PARFITT* Landcare Research, PB 11052, Palmerston North, New Zealand (Received 18 November 2008; revised 18 March 2009; Editor: Balwant Singh) ABSTRACT: The literature on the formation, structure and properties of allophane and imogolite is reviewed, with particular emphasis on the seminal contributions by Colin Farmer. Allophane and imogolite occur not only in volcanic-ash soils but also in other environments. The conditions required for the precipitation of allophane and imogolite are discussed. These include pH, availability of Al and Si, rainfall, leaching regime, and reactions with organic matter. Because of their excellent water storage and physical properties, allophanic soils can accumulate large amounts of biomass. In areas of high rainfall, these soils often occur under rain forest, and the soil organic matter derived from the forest biomass is stabilized by allophane and aluminium ions. Thus the turnover of soil organicmatter in allophanicsoils is slower than that in non-allophanicsoils. The organicmatter appears to be derived from the microbial by-products of the plant material rather than from the plant material itself. The growth of young forests may be limited by nitrogen supply but growth of older forests tends to be P limited. Phosphorus is recycled through both inorganic and organic pathways, but it is also strongly sorbed by Al compounds including allophane. When crops are grown in allophanic soils, large amounts of labile P are required and, accordingly, these soils have to be managed to counteract the large P sorption capacity of allophane and other Al compounds, and to ensure an adequate supply of labile P. -

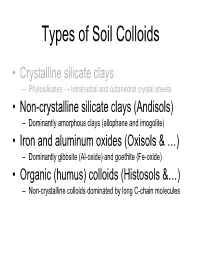

Types of Soil Colloids

Types of Soil Colloids • Crystalline silicate clays – Phylosilicates → tetrahedral and octahedral crystal sheets • Non-crystalline silicate clays (Andisols) – Dominantly amorphous clays (allophane and imogolite) • Iron and aluminum oxides (Oxisols & …) – Dominantly gibbsite (Al-oxide) and goethite (Fe-oxide) • Organic (humus) colloids (Histosols &…) – Non-crystalline colloids dominated by long C-chain molecules Non-crystalline Silicate Clays Allophane and Imogolite 1. Volcanic ash is chemically/mineralogically distinct from most other soil parent materials. 2. Composed largely of vitric or glassy materials containing varying amounts of Al and Si. 3. It lacks a well-defined crystal structure (i.e., amorphous) and is quite soluble. Allophane and Imogolite are common early-stage residual weathering products of volcanic glass and both have poorly-ordered structures. Allophane forms inside glass fragments where Si concentration and pH are high and has a characteristic spherule shape. Imogolite tends to form on the exterior of glass fragments under conditions of lower pH and Si concentration, and has a characteristic thread-like morphology. Iron and Aluminum oxides Sesquioxides Dominantly gibbsite (Al-oxide) and goethite (Fe-oxide) 1. Found in many soils 2. Especially important in highly weathered soils of warm humid regions 3. Consist of mainly either Fe or Al atoms coordinated with O atoms - the O atoms often associated with H ions to make hydroxyl groups 4. Some, such as gibbsite (Al-oxide) and goethite (Fe-oxide), form crystalline sheets 5. Others form amorphous coatings on soil particles Because of surface plane of covalently bonded hydroxyls gives these colloids the capacity to strongly adsorb certain anions Because of surface plane of covalently bonded hydroxyls gives these colloids the capacity to strongly adsorb certain anions Gibbsite (Al-oxide) Goethite (Fe-oxide) amorphous coatings on soil particles Organic (humus) colloids Non-crystalline colloids dominated by long C-chain molecules 1. -

Imogolite Al2sio3(OH)4 C 2001 Mineral Data Publishing, Version 1.2 ° Crystal Data: N.D

Imogolite Al2SiO3(OH)4 c 2001 Mineral Data Publishing, version 1.2 ° Crystal Data: n.d. Point Group: n.d. Conchoidal to earthy; as microscopic threadlike particles, and bundles of ¯ne tubes, each about 20 Aº in diameter. Physical Properties: Fracture: Conchoidal, earthy. Tenacity: Brittle. Hardness = 2{3 D(meas.) = 2.70 D(calc.) = 2.70 Optical Properties: Transparent to translucent. Color: White, blue, green, brown, black. Luster: Vitreous, resinous, waxy. Optical Class: Isotropic. n = 1.47{1.51 Cell Data: Space Group: n.d. c = 8.4; 5.1 c Z = n.d. ? X-ray Powder Pattern: Uemura, Japan; by electron di®raction. 21.0 (100b), 4.12 (100), 1.40 (100), 11.7 (80b), 7.8 (80b), 3.75 (80b), 2.32 (80b) Chemistry: An analysis of natural material does not appear to be available. Occurrence: In soils derived from volcanic ash. Association: Allophane, quartz, cristobalite, gibbsite, vermiculite, \limonite". Distribution: Probably quite widespread in volcanic-ash-derived soils. In the Misutsuchi bed, Iijima, Nagano Prefecture; the Kanumatsuchi bed, Kanuma, Tochigi Prefecture; and from Uemura, Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan. Name: For the name, Imogo, of the brownish yellow volcanic ash soil of Japan in which it occurs. Type Material: n.d. References: (1) Yoshinaga, N. and S. Aomine (1962) Allophane in some Ando soils. Soil Sci. and Plant Nutrition (Japan), 8, 6{13. (2) (1963) Amer. Mineral., 48, 434 (abs. ref. 1). (3) Russell, J.D, W.J. McHardy, and A.R. Fraser (1969) Imogolite: a unique aluminosilicate. Clay Minerals, 8, 87{99. (4) Cradwick, P.D.G., V.C. -

"The Structure of "Imogolite""

THE AMERICAN MINERAI,OGIST, VOL 54, JANUARY FEBRUARY, 1969 THE STRUCTURE OF "IMOGOLITE" Kolr W.Lo.l, F'acultyoJ Agriculture, Kyushu IJnitersity, Fukuoka, J apan AND N.q.cexonrYosurNacl, Facul,tyoJ Agricwlture, Ehi,me LIniaersily, M atsuyama,J apan Assrnecr The structure of "imogolite," first described in 1962, was studied r'vith the type speci- mens formed by weathering of pumice and glassy volcanic ash Chemical analyses give the formula 1.1 SiO:'A1zOr'2 3-Z I HlO (-|) without correction for allophane as an impurity. Difiraction and electron microscopic studies suggested that "imogolite" appears in a para- crystalline state forming threads with diameter 100 to 300 A, which consist of the chain units with the repeat distance, 8.4 A and with the mean in terchain separation, 17 7 A. The density of the imogolite film measured by displacement with water is 2.63 to 2.70, while that measuredby suspensionin heavy liquids is 1.70 to 1.97. The presenceof many micro- pores between the chain units, about 55/6 is estimated from the difference between the two density values and from the maximum adsorption of water vapor. The progressive change of the X-ray pattern and weight loss by heating suggests rearrangement and linking of the chain units at 50 to 250'C, and breakdown of their structure by dehydroxylation above 250"c. t'Imogolite" is structurally distinct both from allophane and from known layer or chain clay minerals. Preliminary analyses indicate a 1 :2 chain structure unit f or "imogolite" with the structural formula (AlsOr' OII:o. -

Chapter 5 Nanomaterials from Imogolite

Chapter 5 Nanomaterials From Imogolite: Structure, Properties and Functional Materials Erwan Paineau,* Pascale Launois* Laboratoire de Physique des Solides, UMR CNRS 8502, Univ. Paris Sud, Université Paris Saclay, 91405 Orsay Cedex, France Corresponding authors: E. Paineau (Email: erwan‐nicolas.paineau@u‐psud.fr); P. Launois (Email: pascale.launois@u‐psud.fr) Abstract Hollow cylinders with a diameter in the nanometer range are carving out prime positions in nanoscience. Thanks to their physico‐chemical properties, they could be key elements for next‐generation nanofluidics devices, for selective molecular sieving, energy conversion or as catalytic nanoreactors. Several difficult problems such as fine diameter and interface control are solved for imogolite nanotubes. This chapter will present an overview of this unique class of clay nanotubes, from their geological occurrence to their synthesis and their applications. In particular, emphasis will be put on providing an up‐to‐date description of their structure and properties, their synthesis and the strategies developed to modify their interfaces in a controlled manner. Developments on their applications, in particular for polymer/imogolite nanotubes composites, molecular confinement or catalysis, are presented. Keywords: Imogolite, nanotube, structure, monodisperse diameter, synthesis, functionalization, charged interface, self‐organization, nanocomposite, molecular sieving, adsorbent 5.1. Occurrence and Distribution of Imogolite Imogolite is a naturally occurring aluminosilicate nanotube, first described in 1962 by Yoshinaga and Aomine, in the Kuma basin in the Kumamoto Prefecture (Japan) [1]. The name of this unknown fibrous mineral has been proposed in reference to the parent material “imogo”, a brownish yellow volcanic ash soil [2,3] (Figure 5.1a‐c). The Commission on New Minerals and Mineral Names of the International Mineralogical Association first concluded that it did not warrant classification as a distinct mineral type [4]. -

The Synthesis of Organoclays Based on Clay Minerals with Different Structural Expansion Capacities

minerals Review The Synthesis of Organoclays Based on Clay Minerals with Different Structural Expansion Capacities Leonid Perelomov 1 , Saglara Mandzhieva 2,* , Tatiana Minkina 2 , Yury Atroshchenko 1, Irina Perelomova 3, Tatiana Bauer 4, David Pinsky 5 and Anatoly Barakhov 2 1 Faculty of Natural Sciences, Tula State Lev Tolstoy Pedagogical University, 300026 Tula, Russia; [email protected] (L.P.); [email protected] (Y.A.) 2 Academy of Biology and Biotechnology, Southern Federal University, 344006 Rostov-on-Don, Russia; [email protected] (T.M.); [email protected] (A.B.) 3 Faculty of Medicine, Tula State University, 300026 Tula, Russia; [email protected] 4 Federal Research Center “Southern Scientific Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences”, Chekhov Street, 344006 Rostov-on-Don, Russia; [email protected] 5 Institute of Physicochemical and Biological Problems in Soil Science of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Institutskaya Street, 2, 142290 Pushchino, Russia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +7-988-896-95-53 Abstract: An important goal in environmental research for industrial activity and sites is the in- vestigation and development of effective adsorbents for chemical pollutants that are widespread, inexpensive, unharmful to the environment, and have the required adsorption selectivity. Organ- oclays are adsorption materials that can be obtained by modifying clays and clay minerals with various organic compounds through intercalation and surface grafting. Organoclays have impor- tant practical applications as adsorbents of a wide range of organic pollutants and some inorganic Citation: Perelomov, L.; Mandzhieva, contaminants. The traditional raw materials for the synthesis of organoclays are phyllosilicates S.; Minkina, T.; Atroshchenko, Y.; with the expanding structural cell of the smectite group, such as montmorillonite. -

Clay Mineral Evolution 4 5 1,2* 1,3 3 4 6 Robert M

1 American Mineralogist MS #4425—Revision 3—June 7, 2013 2 3 Clay mineral evolution 4 5 1,2* 1,3 3 4 6 Robert M. Hazen , Dimitri A. Sverjensky , David Azzolini , David L. Bish , 2 3 5 7 Stephen C. Elmore , Linda Hinnov , Ralph E. Milliken 8 9 1Geophysical Laboratory, Carnegie Institution of Washington, 10 5251 Broad Branch Road NW, Washington, D. C. 20015, USA. 11 2George Mason University, 4400 University Drive, Fairfax, VA 20444, USA. 12 3Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA 13 4Department of Geological Sciences, Indiana University 1001 E. 10th St., Bloomington IN 47405, USA. 14 5Department of Geological Sciences, Brown University, Box 1864, Providence, RI 02912 USA 15 16 ABSTRACT 17 Changes in the mechanisms of formation and global distribution of phyllosilicate clay 18 minerals through 4.567 Ga of planetary evolution in our Solar System reflect evolving tectonic, 19 geochemical, and biological processes. Clay minerals were absent prior to planetesimal 20 formation approximately 4.6 billion years ago but today are abundant in all near-surface Earth 21 environments. New clay mineral species and modes of clay mineral paragenesis occurred as a 22 consequence of major events in Earth’s evolution—notably the formation of a mafic crust and 23 oceans, the emergence of granite-rooted continents, the initiation of plate tectonics and 24 subduction, the Great Oxidation Event, and the rise of the terrestrial biosphere. The changing 25 character of clay minerals through time is thus an important part of Earth’s mineralogical history 26 and exemplifies the principles of mineral evolution.