Arxiv:1309.5421V2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FY08 Technical Papers by GSMTPO Staff

AURA/NOAO ANNUAL REPORT FY 2008 Submitted to the National Science Foundation July 23, 2008 Revised as Complete and Submitted December 23, 2008 NGC 660, ~13 Mpc from the Earth, is a peculiar, polar ring galaxy that resulted from two galaxies colliding. It consists of a nearly edge-on disk and a strongly warped outer disk. Image Credit: T.A. Rector/University of Alaska, Anchorage NATIONAL OPTICAL ASTRONOMY OBSERVATORY NOAO ANNUAL REPORT FY 2008 Submitted to the National Science Foundation December 23, 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................. 1 1 SCIENTIFIC ACTIVITIES AND FINDINGS ..................................................................................... 2 1.1 Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory...................................................................................... 2 The Once and Future Supernova η Carinae...................................................................................................... 2 A Stellar Merger and a Missing White Dwarf.................................................................................................. 3 Imaging the COSMOS...................................................................................................................................... 3 The Hubble Constant from a Gravitational Lens.............................................................................................. 4 A New Dwarf Nova in the Period Gap............................................................................................................ -

Messier Objects

Messier Objects From the Stocker Astroscience Center at Florida International University Miami Florida The Messier Project Main contributors: • Daniel Puentes • Steven Revesz • Bobby Martinez Charles Messier • Gabriel Salazar • Riya Gandhi • Dr. James Webb – Director, Stocker Astroscience center • All images reduced and combined using MIRA image processing software. (Mirametrics) What are Messier Objects? • Messier objects are a list of astronomical sources compiled by Charles Messier, an 18th and early 19th century astronomer. He created a list of distracting objects to avoid while comet hunting. This list now contains over 110 objects, many of which are the most famous astronomical bodies known. The list contains planetary nebula, star clusters, and other galaxies. - Bobby Martinez The Telescope The telescope used to take these images is an Astronomical Consultants and Equipment (ACE) 24- inch (0.61-meter) Ritchey-Chretien reflecting telescope. It has a focal ratio of F6.2 and is supported on a structure independent of the building that houses it. It is equipped with a Finger Lakes 1kx1k CCD camera cooled to -30o C at the Cassegrain focus. It is equipped with dual filter wheels, the first containing UBVRI scientific filters and the second RGBL color filters. Messier 1 Found 6,500 light years away in the constellation of Taurus, the Crab Nebula (known as M1) is a supernova remnant. The original supernova that formed the crab nebula was observed by Chinese, Japanese and Arab astronomers in 1054 AD as an incredibly bright “Guest star” which was visible for over twenty-two months. The supernova that produced the Crab Nebula is thought to have been an evolved star roughly ten times more massive than the Sun. -

THE 1000 BRIGHTEST HIPASS GALAXIES: H I PROPERTIES B

The Astronomical Journal, 128:16–46, 2004 July A # 2004. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. THE 1000 BRIGHTEST HIPASS GALAXIES: H i PROPERTIES B. S. Koribalski,1 L. Staveley-Smith,1 V. A. Kilborn,1, 2 S. D. Ryder,3 R. C. Kraan-Korteweg,4 E. V. Ryan-Weber,1, 5 R. D. Ekers,1 H. Jerjen,6 P. A. Henning,7 M. E. Putman,8 M. A. Zwaan,5, 9 W. J. G. de Blok,1,10 M. R. Calabretta,1 M. J. Disney,10 R. F. Minchin,10 R. Bhathal,11 P. J. Boyce,10 M. J. Drinkwater,12 K. C. Freeman,6 B. K. Gibson,2 A. J. Green,13 R. F. Haynes,1 S. Juraszek,13 M. J. Kesteven,1 P. M. Knezek,14 S. Mader,1 M. Marquarding,1 M. Meyer,5 J. R. Mould,15 T. Oosterloo,16 J. O’Brien,1,6 R. M. Price,7 E. M. Sadler,13 A. Schro¨der,17 I. M. Stewart,17 F. Stootman,11 M. Waugh,1, 5 B. E. Warren,1, 6 R. L. Webster,5 and A. E. Wright1 Received 2002 October 30; accepted 2004 April 7 ABSTRACT We present the HIPASS Bright Galaxy Catalog (BGC), which contains the 1000 H i brightest galaxies in the southern sky as obtained from the H i Parkes All-Sky Survey (HIPASS). The selection of the brightest sources is basedontheirHi peak flux density (Speak k116 mJy) as measured from the spatially integrated HIPASS spectrum. 7 ; 10 The derived H i masses range from 10 to 4 10 M . -

![Arxiv:1904.06897V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 15 Apr 2019](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4180/arxiv-1904-06897v1-astro-ph-sr-15-apr-2019-384180.webp)

Arxiv:1904.06897V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 15 Apr 2019

MNRAS 000,1–16 (2019) Preprint 16 April 2019 Compiled using MNRAS LATEX style file v3.0 The Sejong Open cluster Survey (SOS) VI. A small star-forming region in the high Galactic latitude molecular cloud MBM 110 Hwankyung Sung1?, Michael S. Bessell2, Inseok Song3 1Department of Physics and Astronomy, Sejong University, 209 Neungdong-ro, Gwangjin-gu, Seoul 05006, Korea 2Research School of Astronomy & Astrophysics, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2611, Australia 3Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA Last updated 2019 March 25 ABSTRACT We present optical photometric, spectroscopic data for the stars in the high Galactic latitude molecular cloud MBM 110. For the complete membership selection of MBM 110, we also analyze WISE mid-infrared data and Gaia astrometric data. Membership of individual stars is critically evaluated using the data mentioned above. The Gaia parallax of stars in MBM 110 is 2.667 ± 0.095 mas (d = 375 ± 13pc), which confirms that MBM 110 is a small star-forming region in the Orion-Eridanus superbubble. The age of MBM 110 is between 1.9 Myr and 3.1 Myr depending on the adopted pre-main sequence evolution model. The total stellar mass of MBM 110 is between 16 M (members only) and 23 M (including probable members). The star formation efficiency is estimated to be about 1.4%. We discuss the importance of such small star formation regions in the context of the global star formation rate and suggest that a galaxy’s star formation rate calculated from the Hα luminosity may underestimate the actual star formation rate. -

![Arxiv:2009.04090V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 14 Sep 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4020/arxiv-2009-04090v2-astro-ph-ga-14-sep-2020-474020.webp)

Arxiv:2009.04090V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 14 Sep 2020

Research in Astronomy and Astrophysics manuscript no. (LATEX: tikhonov˙Dorado.tex; printed on September 15, 2020; 1:01) Distance to the Dorado galaxy group N.A. Tikhonov1, O.A. Galazutdinova1 Special Astrophysical Observatory, Nizhnij Arkhyz, Karachai-Cherkessian Republic, Russia 369167; [email protected] Abstract Based on the archival images of the Hubble Space Telescope, stellar photometry of the brightest galaxies of the Dorado group:NGC 1433, NGC1533,NGC1566and NGC1672 was carried out. Red giants were found on the obtained CM diagrams and distances to the galaxies were measured using the TRGB method. The obtained values: 14.2±1.2, 15.1±0.9, 14.9 ± 1.0 and 15.9 ± 0.9 Mpc, show that all the named galaxies are located approximately at the same distances and form a scattered group with an average distance D = 15.0 Mpc. It was found that blue and red supergiants are visible in the hydrogen arm between the galaxies NGC1533 and IC2038, and form a ring structure in the lenticular galaxy NGC1533, at a distance of 3.6 kpc from the center. The high metallicity of these stars (Z = 0.02) indicates their origin from NGC1533 gas. Key words: groups of galaxies, Dorado group, stellar photometry of galaxies: TRGB- method, distances to galaxies, galaxies NGC1433, NGC 1533, NGC1566, NGC1672 1 INTRODUCTION arXiv:2009.04090v2 [astro-ph.GA] 14 Sep 2020 A concentration of galaxies of different types and luminosities can be observed in the southern constella- tion Dorado. Among them, Shobbrook (1966) identified 11 galaxies, which, in his opinion, constituted one group, which he called “Dorado”. -

The Outermost Hii Regions of Nearby Galaxies

THE OUTERMOST HII REGIONS OF NEARBY GALAXIES by Jessica K. Werk A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Astronomy and Astrophysics) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor Mario L. Mateo, Co-Chair Associate Professor Mary E. Putman, Co-Chair, Columbia University Professor Fred C. Adams Professor Lee W. Hartmann Associate Professor Marion S. Oey Professor Gerhardt R. Meurer, University of Western Australia Jessica K. Werk Copyright c 2010 All Rights Reserved To Mom and Dad, for all your love and encouragement while I was taking up space. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I owe a deep debt of gratitude to a long list of individuals, institutions, and substances that have seen me through the last six years of graduate school. My first undergraduate advisor in Astronomy, Kathryn Johnston, was also my first Astronomy Professor. She piqued my interest in the subject from day one with her enthusiasm and knowledge. I don’t doubt that I would be studying something far less interesting if it weren’t for her. John Salzer, my next and last undergraduate advisor, not only taught me so much about observing and organization, but also is responsible for convincing me to go on in Astronomy. Were it not for John, I’d probably be making a lot more money right now doing something totally mind-numbing and soul-crushing. And Laura Chomiuk, a fellow Wesleyan Astronomy Alumnus, has been there for me through everything − problem sets and personal heartbreak alike. To know her as a friend, goat-lover, and scientist has meant so much to me over the last 10 years, that confining my gratitude to these couple sentences just seems wrong. -

Emission Nebulae

PART 3 Galaxies Gas, Stars and stellar motion in the “Milky Way” The Interstellar Medium The Sombrero Galaxy • Space is far from empty! • This dust can obscure visible light – Clouds of cold gas from stars and appear to be vast – Clouds of dust tracts of empty space • In a galaxy, gravity pulls the dust • Fortunately, it doesn’t hide all into a disk along and within the galactic plane wavelengths of light! Emission Nebulae • We frequently see nebulae (clouds of interstellar gas and dust) glowing faintly with a red or pink color • Ultraviolet radiation from nearby hot stars heats the nebula, causing it to emit photons • This is an emission nebula! Reflection Nebulae • When the cloud of gas and dust is simply illuminated by nearby stars, the light reflects, creating a reflection nebula • Typically glows blue Dark Nebulae • Nebulae that are not illuminated or heated by nearby stars are opaque – they block most of the visible light passing through it. • This is a dark nebula Interstellar Reddening • As starlight passes through a dust cloud, the dust particles scatter blue photons, allowing red photons to pass through easily • The star appears red (reddening) – it looks older and dimmer (extinction) than it really is. If one region of the sky shows nearby stars but no distant stars or galaxies, our view is probably blocked by a) nothing, but directed toward a particularly empty region of space. b) an emission nebula of ionized gas. c) an interstellar gas and dust cloud. d) a concentration of dark matter. Rotation in the Milky Way • The Milky Way does not rotate like a solid disk! – Inner parts rotate about the center faster than outer parts – Similar to the way planets rotate around the Sun – This is called differential rotation. -

Curriculum Vitae John P

Curriculum Vitae John P. Blakeslee National Research Council of Canada Phone: 1-250-363-8103 Herzberg Astronomy & Astrophysics Programs Fax: 1-250-363-0045 5071 West Saanich Road Cell: 1-250-858-1357 Victoria, B.C. V9E 2E7 Email: [email protected] Canada Citizenship: USA Education 1997 Ph.D., Physics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (supervisor: Prof. John Tonry) 1991 B. A., Physics, University of Chicago (Honors; supervisor: Prof. Donald York) Employment History 2007 – present Astronomer, Senior Research Officer NRC Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics 2008 – present Adjunct Associate Professor Department of Physics, University of Victoria 2008 – 2013 Adjunct Professor Washington State University 2005 – 2007 Assistant Professor of Physics Washington State University 2004 – 2005 Research Scientist Johns Hopkins University 2000 – 2004 Associate Research Scientist Johns Hopkins University 1999 – 2000 Postdoctoral Research Associate University of Durham, U.K. 1996 – 1999 Fairchild Postdoctoral Scholar California Institute of Technology Fellowships and Awards 2004 Ernest F. Fullam Award for Innovative Research in Astronomy, Dudley Observatory 2003 NASA Certificate for contributions to the success of HST Servicing Mission 3B 1996 – 1999 Sherman M. Fairchild Postdoctoral Fellowship in Astronomy, Caltech Professional Service 2016 – present Canadian Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST) Consortium, Co-PI 2014 – present Chair, NOAO Time Allocation Committee (TAC) Extragalactic Panel 2008 – present National Representative, Gemini International -

Gas and Dust in the Magellanic Clouds

Gas and dust in the Magellanic clouds A Thesis Submitted for the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Physics To Mangalore University by Ananta Charan Pradhan Under the Supervision of Prof. Jayant Murthy Indian Institute of Astrophysics Bangalore - 560 034 India April 2011 Declaration of Authorship I hereby declare that the matter contained in this thesis is the result of the inves- tigations carried out by me at Indian Institute of Astrophysics, Bangalore, under the supervision of Professor Jayant Murthy. This work has not been submitted for the award of any degree, diploma, associateship, fellowship, etc. of any university or institute. Signed: Date: ii Certificate This is to certify that the thesis entitled ‘Gas and Dust in the Magellanic clouds’ submitted to the Mangalore University by Mr. Ananta Charan Pradhan for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the faculty of Science, is based on the results of the investigations carried out by him under my supervi- sion and guidance, at Indian Institute of Astrophysics. This thesis has not been submitted for the award of any degree, diploma, associateship, fellowship, etc. of any university or institute. Signed: Date: iii Dedicated to my parents ========================================= Sri. Pandab Pradhan and Smt. Kanak Pradhan ========================================= Acknowledgements It has been a pleasure to work under Prof. Jayant Murthy. I am grateful to him for giving me full freedom in research and for his guidance and attention throughout my doctoral work inspite of his hectic schedules. I am indebted to him for his patience in countless reviews and for his contribution of time and energy as my guide in this project. -

Carbon Stars T. Lloyd Evans

J. Astrophys. Astr. (2010) 31, 177–211 Carbon Stars T. Lloyd Evans SUPA, School of Physics and Astronomy, University of St. Andrews, North Haugh, St. Andrews, Fife KY16 9SS, UK. e-mail: [email protected] Received 2010 July 19; accepted 2010 October 18 Abstract. In this paper, the present state of knowledge of the carbon stars is discussed. Particular attention is given to issues of classification, evolution, variability, populations in our own and other galaxies, and circumstellar material. Key words. Stars: carbon—stars: evolution—stars: circumstellar matter —galaxies: magellanic clouds. 1. Introduction Carbon stars have been reviewed on several previous occasions, most recently by Wallerstein & Knapp (1998). A conference devoted to this topic was held in 1996 (Wing 2000) and two meetings on AGB stars (Le Bertre et al. 1999; Kerschbaum et al. 2007) also contain much on carbon stars. This review emphasizes develop- ments since 1997, while paying particular attention to connections with earlier work and to some of the important sources of concepts. Recent and ongoing develop- ments include surveys for carbon stars in more of the galaxies of the local group and detailed spectroscopy and infrared photometry for many of them, as well as general surveys such as 2MASS, AKARI and the Sirius near infrared survey of the Magel- lanic Clouds and several dwarf galaxies, the Spitzer-SAGE mid-infrared survey of the Magellanic Clouds and the current Herschel infrared satellite project. Detailed studies of relatively bright galactic examples continue to be made by high-resolution spectroscopy, concentrating on abundance determinations using the red spectral region, and infrared and radio observations which give information on the history of mass loss. -

407 a Abell Galaxy Cluster S 373 (AGC S 373) , 351–353 Achromat

Index A Barnard 72 , 210–211 Abell Galaxy Cluster S 373 (AGC S 373) , Barnard, E.E. , 5, 389 351–353 Barnard’s loop , 5–8 Achromat , 365 Barred-ring spiral galaxy , 235 Adaptive optics (AO) , 377, 378 Barred spiral galaxy , 146, 263, 295, 345, 354 AGC S 373. See Abell Galaxy Cluster Bean Nebulae , 303–305 S 373 (AGC S 373) Bernes 145 , 132, 138, 139 Alnitak , 11 Bernes 157 , 224–226 Alpha Centauri , 129, 151 Beta Centauri , 134, 156 Angular diameter , 364 Beta Chamaeleontis , 269, 275 Antares , 129, 169, 195, 230 Beta Crucis , 137 Anteater Nebula , 184, 222–226 Beta Orionis , 18 Antennae galaxies , 114–115 Bias frames , 393, 398 Antlia , 104, 108, 116 Binning , 391, 392, 398, 404 Apochromat , 365 Black Arrow Cluster , 73, 93, 94 Apus , 240, 248 Blue Straggler Cluster , 169, 170 Aquarius , 339, 342 Bok, B. , 151 Ara , 163, 169, 181, 230 Bok Globules , 98, 216, 269 Arcminutes (arcmins) , 288, 383, 384 Box Nebula , 132, 147, 149 Arcseconds (arcsecs) , 364, 370, 371, 397 Bug Nebula , 184, 190, 192 Arditti, D. , 382 Butterfl y Cluster , 184, 204–205 Arp 245 , 105–106 Bypass (VSNR) , 34, 38, 42–44 AstroArt , 396, 406 Autoguider , 370, 371, 376, 377, 388, 389, 396 Autoguiding , 370, 376–378, 380, 388, 389 C Caldwell Catalogue , 241 Calibration frames , 392–394, 396, B 398–399 B 257 , 198 Camera cool down , 386–387 Barnard 33 , 11–14 Campbell, C.T. , 151 Barnard 47 , 195–197 Canes Venatici , 357 Barnard 51 , 195–197 Canis Major , 4, 17, 21 S. Chadwick and I. Cooper, Imaging the Southern Sky: An Amateur Astronomer’s Guide, 407 Patrick Moore’s Practical -

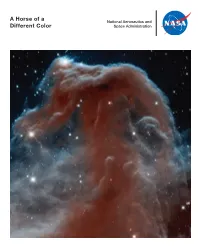

A Horse of a Different Color

A Horse of a National Aeronautics and Different Color Space Administration A Horse of a Different Color To celebrate the 23rd anniversary of the Hubble Space Telescope, NASA released a new view of the Horsehead Nebula that provides an intriguing astronomical variation on the phrase, “a horse of a different color.” The Horsehead Nebula, also known as Barnard 33, was first recorded in 1888 by Williamina Fleming at the Harvard College Observatory. Visible-light images show a black silhouette, a “dark nebula,” that resembles a horse’s head. Dark nebulae are generally most noticeable because they block the light from background stars. Two views of Horsehead Nebula To see deeper into dark nebulae, astronomers use infrared These two images reveal different views of the Horsehead Nebula. The visible-light image on the left was taken by a ground-based light. Hubble’s infrared image of the Horsehead transforms telescope. The near-infrared image on the right was taken by the the dark nebula into a softly glowing landscape. The image Hubble Space Telescope. reveals more structure and detail in the clouds. In the image at left, the gas around the Horsehead Nebula shines Many parts of the Horsehead Nebula are still opaque at infrared a bright pink, in contrast to the darkness of the Horsehead itself. This pink glow occurs along the edge of the dark cloud and is wavelengths, showing that the gas is dense and cold. Within created by the bright star, Sigma Orionis, above the Horsehead, such cold and dense clouds are regions where stars are born.