Arxiv:1904.06897V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 15 Apr 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Messier Objects

Messier Objects From the Stocker Astroscience Center at Florida International University Miami Florida The Messier Project Main contributors: • Daniel Puentes • Steven Revesz • Bobby Martinez Charles Messier • Gabriel Salazar • Riya Gandhi • Dr. James Webb – Director, Stocker Astroscience center • All images reduced and combined using MIRA image processing software. (Mirametrics) What are Messier Objects? • Messier objects are a list of astronomical sources compiled by Charles Messier, an 18th and early 19th century astronomer. He created a list of distracting objects to avoid while comet hunting. This list now contains over 110 objects, many of which are the most famous astronomical bodies known. The list contains planetary nebula, star clusters, and other galaxies. - Bobby Martinez The Telescope The telescope used to take these images is an Astronomical Consultants and Equipment (ACE) 24- inch (0.61-meter) Ritchey-Chretien reflecting telescope. It has a focal ratio of F6.2 and is supported on a structure independent of the building that houses it. It is equipped with a Finger Lakes 1kx1k CCD camera cooled to -30o C at the Cassegrain focus. It is equipped with dual filter wheels, the first containing UBVRI scientific filters and the second RGBL color filters. Messier 1 Found 6,500 light years away in the constellation of Taurus, the Crab Nebula (known as M1) is a supernova remnant. The original supernova that formed the crab nebula was observed by Chinese, Japanese and Arab astronomers in 1054 AD as an incredibly bright “Guest star” which was visible for over twenty-two months. The supernova that produced the Crab Nebula is thought to have been an evolved star roughly ten times more massive than the Sun. -

Emission Nebulae

PART 3 Galaxies Gas, Stars and stellar motion in the “Milky Way” The Interstellar Medium The Sombrero Galaxy • Space is far from empty! • This dust can obscure visible light – Clouds of cold gas from stars and appear to be vast – Clouds of dust tracts of empty space • In a galaxy, gravity pulls the dust • Fortunately, it doesn’t hide all into a disk along and within the galactic plane wavelengths of light! Emission Nebulae • We frequently see nebulae (clouds of interstellar gas and dust) glowing faintly with a red or pink color • Ultraviolet radiation from nearby hot stars heats the nebula, causing it to emit photons • This is an emission nebula! Reflection Nebulae • When the cloud of gas and dust is simply illuminated by nearby stars, the light reflects, creating a reflection nebula • Typically glows blue Dark Nebulae • Nebulae that are not illuminated or heated by nearby stars are opaque – they block most of the visible light passing through it. • This is a dark nebula Interstellar Reddening • As starlight passes through a dust cloud, the dust particles scatter blue photons, allowing red photons to pass through easily • The star appears red (reddening) – it looks older and dimmer (extinction) than it really is. If one region of the sky shows nearby stars but no distant stars or galaxies, our view is probably blocked by a) nothing, but directed toward a particularly empty region of space. b) an emission nebula of ionized gas. c) an interstellar gas and dust cloud. d) a concentration of dark matter. Rotation in the Milky Way • The Milky Way does not rotate like a solid disk! – Inner parts rotate about the center faster than outer parts – Similar to the way planets rotate around the Sun – This is called differential rotation. -

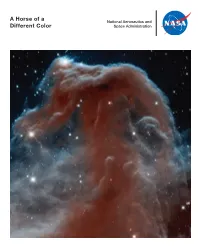

A Horse of a Different Color

A Horse of a National Aeronautics and Different Color Space Administration A Horse of a Different Color To celebrate the 23rd anniversary of the Hubble Space Telescope, NASA released a new view of the Horsehead Nebula that provides an intriguing astronomical variation on the phrase, “a horse of a different color.” The Horsehead Nebula, also known as Barnard 33, was first recorded in 1888 by Williamina Fleming at the Harvard College Observatory. Visible-light images show a black silhouette, a “dark nebula,” that resembles a horse’s head. Dark nebulae are generally most noticeable because they block the light from background stars. Two views of Horsehead Nebula To see deeper into dark nebulae, astronomers use infrared These two images reveal different views of the Horsehead Nebula. The visible-light image on the left was taken by a ground-based light. Hubble’s infrared image of the Horsehead transforms telescope. The near-infrared image on the right was taken by the the dark nebula into a softly glowing landscape. The image Hubble Space Telescope. reveals more structure and detail in the clouds. In the image at left, the gas around the Horsehead Nebula shines Many parts of the Horsehead Nebula are still opaque at infrared a bright pink, in contrast to the darkness of the Horsehead itself. This pink glow occurs along the edge of the dark cloud and is wavelengths, showing that the gas is dense and cold. Within created by the bright star, Sigma Orionis, above the Horsehead, such cold and dense clouds are regions where stars are born. -

Optical and UV Surface Brightness of Translucent Dark Nebulae ? Dust Albedo, Radiation field, and fluorescence Emission by H2 K

A&A 617, A42 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201833196 Astronomy & © ESO 2018 Astrophysics Optical and UV surface brightness of translucent dark nebulae ? Dust albedo, radiation field, and fluorescence emission by H2 K. Mattila1, M. Haas2, L. K. Haikala3, Y-S. Jo4, K. Lehtinen1,8, Ch. Leinert5, and P. Väisänen6,7 1 Department of Physics, University of Helsinki, PO Box 64, 00014 Helsinki, Finland e-mail: [email protected] 2 Astronomisches Institut, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Universitätsstrasse 150, 44801 Bochum, Germany 3 Instituto de Astronomía y Ciencias Planetarias de Atacama, Universidad de Atacama, Copayapu 485, Copiapo, Chile 4 Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute (KASI), 776 Daedeokdae-ro, Yuseong-gu, Daejeon 305-348, Korea 5 Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie, Königstuhl 17, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany 6 South African Astronomical Observatory, PO Box 9 Observatory, Cape Town, South Africa 7 Southern African Large Telescope, PO Box 9 Observatory, Cape Town, South Africa 8 Finnish Geospatial Research Institute FGI, Geodeetinrinne 2, 02430 Masala, Finland Received 9 April 2018 / Accepted 27 May 2018 ABSTRACT Context. Dark nebulae display a surface brightness because dust grains scatter light of the general interstellar radiation field (ISRF). High-galactic-latitudes dark nebulae are seen as bright nebulae when surrounded by transparent areas which have less scattered light from the general galactic dust layer. Aims. Photometry of the bright dark nebulae LDN 1780, LDN 1642, and LBN 406 shall be used to derive scattering properties of dust and to investigate the presence of UV fluorescence emission by molecular hydrogen and the extended red emission (ERE). -

E. E. Barnard and His Dark Nebula!

Visible throughout our galaxy are clouds of interstellar matter, thin but widespread wisps of gas and dust. Some of the stars near nebulae are often very massive and their high-energy radiation can excite the gas of the nebula to shine; such nebula is called emission nebula. If the stars are dimmer or further away, their light is reflected by the dust in the nebula and can be seen as reflection nebula. Some nebulae are only visible by the absorption of the light from objects behind them. These are called dark nebula Edward Emerson Barnard was a professor of astronomy at the University of Chicago Yerkes Observatory. As a pioneer in astrophotography, he cataloged a series of dark nebula of the Milky Way. Through this work of studying the structure of the Milky Way, Barnard discovered that certain dark regions of our galaxy are actually clouds of gas and dust that obscured the more distant stars in the background. Today, we’re going to look-back on his life and accomplishments. We’ll also review several of my observations of his dark nebula. Barnard’s Early Years: A: Childhood, Work, and Stargazing Edward Emerson Barnard was born on December 16th, 1857 in Nashville Tennessee, at the cusp of the Civil War. His mother, Elizabeth, (at the age of 42), had moved the family from Cincinnati to Nashville a few months prior to Edward’s birth, when his father, Reuben Barnard had passed away. The family lived in near poverty, with Elizabeth as the sole provider working several small jobs, the most profitable being that of her making wax flowers, which she had a skill at creating. -

'This Is Not a Pipe': Curious Dark Nebula Seen As Never Before 15 August 2012

'This is not a pipe': Curious dark nebula seen as never before 15 August 2012 were areas in space where there were no stars. But it was later discovered that dark nebulae actually consist of clouds of interstellar dust so thick it can block out the light from the stars beyond. The Pipe Nebula appears silhouetted against the rich star clouds close to the centre of the Milky Way in the constellation of Ophiuchus (The Serpent Bearer). Barnard 59 forms the mouthpiece of the Pipe Nebula and is the subject of this new image from the Wide Field Imager on the MPG/ESO 2.2-metre telescope. This strange and complex dark nebula lies about 600-700 light-years away from Earth. The nebula is named after the American astronomer Edward Emerson Barnard who was the first to systematically record dark nebulae using long-exposure photography and one of those who recognised their dusty nature. Barnard catalogued a total of 370 dark nebulae all over the sky. A self- This picture shows Barnard 59, part of a vast dark cloud made man, he bought his first house with the prize of interstellar dust called the Pipe Nebula. This new and money from discovering several comets. Barnard very detailed image of what is known as a dark nebula was an extraordinary observer with exceptional was captured by the Wide Field Imager on the eyesight who made contributions in many fields of MPG/ESO 2.2-meter telescope at ESO's La Silla astronomy in the late 19th and early 20th century. -

Pennsylvania Science Olympiad Southeast Regional Tournament 2013 Astronomy C Division Exam March 4, 2013

PENNSYLVANIA SCIENCE OLYMPIAD SOUTHEAST REGIONAL TOURNAMENT 2013 ASTRONOMY C DIVISION EXAM MARCH 4, 2013 SCHOOL:________________________________________ TEAM NUMBER:_________________ INSTRUCTIONS: 1. Turn in all exam materials at the end of this event. Missing exam materials will result in immediate disqualification of the team in question. There is an exam packet as well as a blank answer sheet. 2. You may separate the exam pages. You may write in the exam. 3. Only the answers provided on the answer page will be considered. Do not write outside the designated spaces for each answer. 4. Include school name and school code number at the bottom of the answer sheet. Indicate the names of the participants legibly at the bottom of the answer sheet. Be prepared to display your wristband to the supervisor when asked. 5. Each question is worth one point. Tiebreaker questions are indicated with a (T#) in which the number indicates the order of consultation in the event of a tie. Tiebreaker questions count toward the overall raw score, and are only used as tiebreakers when there is a tie. In such cases, (T1) will be examined first, then (T2), and so on until the tie is broken. There are 12 tiebreakers. 6. When the time is up, the time is up. Continuing to write after the time is up risks immediate disqualification. 7. In the BONUS box on the answer sheet, name the gentleman depicted on the cover for a bonus point. 8. As per the 2013 Division C Rules Manual, each team is permitted to bring “either two laptop computers OR two 3-ring binders of any size, or one binder and one laptop” and programmable calculators. -

Astronomy Magazine 2011 Index Subject Index

Astronomy Magazine 2011 Index Subject Index A AAVSO (American Association of Variable Star Observers), 6:18, 44–47, 7:58, 10:11 Abell 35 (Sharpless 2-313) (planetary nebula), 10:70 Abell 85 (supernova remnant), 8:70 Abell 1656 (Coma galaxy cluster), 11:56 Abell 1689 (galaxy cluster), 3:23 Abell 2218 (galaxy cluster), 11:68 Abell 2744 (Pandora's Cluster) (galaxy cluster), 10:20 Abell catalog planetary nebulae, 6:50–53 Acheron Fossae (feature on Mars), 11:36 Adirondack Astronomy Retreat, 5:16 Adobe Photoshop software, 6:64 AKATSUKI orbiter, 4:19 AL (Astronomical League), 7:17, 8:50–51 albedo, 8:12 Alexhelios (moon of 216 Kleopatra), 6:18 Altair (star), 9:15 amateur astronomy change in construction of portable telescopes, 1:70–73 discovery of asteroids, 12:56–60 ten tips for, 1:68–69 American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO), 6:18, 44–47, 7:58, 10:11 American Astronomical Society decadal survey recommendations, 7:16 Lancelot M. Berkeley-New York Community Trust Prize for Meritorious Work in Astronomy, 3:19 Andromeda Galaxy (M31) image of, 11:26 stellar disks, 6:19 Antarctica, astronomical research in, 10:44–48 Antennae galaxies (NGC 4038 and NGC 4039), 11:32, 56 antimatter, 8:24–29 Antu Telescope, 11:37 APM 08279+5255 (quasar), 11:18 arcminutes, 10:51 arcseconds, 10:51 Arp 147 (galaxy pair), 6:19 Arp 188 (Tadpole Galaxy), 11:30 Arp 273 (galaxy pair), 11:65 Arp 299 (NGC 3690) (galaxy pair), 10:55–57 ARTEMIS spacecraft, 11:17 asteroid belt, origin of, 8:55 asteroids See also names of specific asteroids amateur discovery of, 12:62–63 -

2017Spring.Astronomyweek2.Pdf

1 The le' image is an ar/st’s concept of what the Milky Way would look like from above. The right image is galaxy M109, a spiral galaxy that is thought to resemble the Milky Way. 2 Time-lapse video of the Milky Way 3 Top view: The Milky Way as seen in visible light. The dark areas are lanes of dust that block out visible light. BoIom view: An infrared view of the Milky Way. The longer wavelength infrared light is able to penetrate dust very well, allowing us to see much more of the stars in our galaxy. 4 Jupiter and its four largest moons as seen through a decent-sized telescope on a clear night. 5 Image of Jupiter from the Cassini probe as it passed the planet for a gravity assist on its way to Saturn. The large spot on Jupiter is the Great Red Spot - a storm that is 2-3 /mes as big as Earth and that has been observed for at least 350 years. 6 A quick snapshot of Jupiter through a small telescope that highlights the ease of seeing the four largest moons. The inset is a record kept by Galileo of the moons posi/ons over the course of a couple of weeks. 7 8 9 Images taken by the New Horizons probe as it got a gravity assist from Jupiter on its way to Pluto. The plume of Tvashtar is several hundred kilometers high. Note that you can see some of the night side of Io very well due to light being reflected from Jupiter. -

Sirius Astronomer Newsletter

JULY 2013 Free to members, subscriptions $12 for 12 Volume 40, Number 7 The Trifid Nebula, M20, is shown in this recent image created by John Castillo from the Anza site. This image is the product of over eight hours of imaging with 7-minute RGB subs through a 12.5-inch telescope. Located 5,000 light-years from Earth in the prominent summer constellation Sagittarius, M20 is unusual in that it is composed of three separate objects: an open cluster; an emission nebula; and a dark nebula giving the object its trifid-like appearance. At magnitude 6.3, it is an easy object for be- ginners with modest equipment. OCA CLUB MEETING STAR PARTIES COMING UP The free and open club meeting will The Black Star Canyon site will open on July The next session of the Beginners be held July 12 at 7:30 PM in the Ir- 13. The Anza site will be open on July 6. Class will be held at the Heritage Mu- vine Lecture Hall of the Hashinger Sci- Members are encouraged to check the seum of Orange County at 3101 West ence Center at Chapman University in website calendar for the latest updates on Harvard Street in Santa Ana on Au- Orange. This month, Dr. Joshua Smith star parties and other events. gust 2. The following class will be from CSUF will present ‘Gravitational held September 6. Wave Astronomy with LIGO: Opening Please check the website calendar for the a New Window on the Universe.’ outreach events this month! Volunteers are GOTO SIG: TBA always welcome! Astro-Imagers SIG: July 16, Aug. -

Imaging Van Den Bergh Objects

Deep-sky observing Explore the sky’s spooky reflection nebulae vdB 14 You’ll need a big scope and a dark sky to explore the van den Bergh catalog’s challenging objects. text and images by Thomas V. Davis vdB 15 eflection nebulae are the unsung sapphires of the sky. These vast R glowing regions represent clouds of dust and cold hydrogen scattered throughout the Milky Way. Reflection nebulae mainly glow with subtle blue light because of scattering — the prin- ciple that gives us our blue daytime sky. Unlike the better-known red emission nebulae, stars associated with reflection nebulae are not near enough or hot enough to cause the nebula’s gas to ion- ize. Ionization is what gives hydrogen that characteristic red color. The star in a reflection nebula merely illuminates sur- rounding dust and gas. Many catalogs containing bright emis- sion nebulae and fascinating planetary nebulae exist. Conversely, there’s only one major catalog of reflection nebulae. The Iris Nebula (NGC 7023) also carries the designation van den Bergh (vdB) 139. This beauti- ful, flower-like cloud of gas and dust sits in Cepheus. The author combined a total of 6 hours and 6 minutes of exposures to record the faint detail in this image. Reflections of starlight Canadian astronomer Sidney van den vdB 14 and vdB 15 in Camelopardalis are Bergh published a list of reflection nebu- so faint they essentially lie outside the lae in The Astronomical Journal in 1966. realm of visual observers. This LRGB image combines 330 minutes of unfiltered (L) His intent was to catalog “all BD and CD exposures, 70 minutes through red (R) and stars north of declination –33° which are blue (B) filters, and 60 minutes through a surrounded by reflection nebulosity …” green (G) filter. -

Gas, Dust & Starlight

Astronomy 218 Gas, Dust & Starlight Five Phases Observations like these reveal 5 different phases for gas in the interstellar medium. 1) Cold Molecular Clouds (n > 109 m−3, T ~ 10 K) 2) Cold Neutral Medium (n ~ 108 m−3, T ~ 100 K) also called HI regions. 3) Warm Neutral Medium (n ~ 4 ×105 m−3, T ~ 7000 K) also called the Intercloud Medium. 4) Warm Ionized Medium (n ~ 106 m−3, T ~ 104 K) also called HII regions. 5) Hot Ionized Medium (n < 104 m−3, T ~ 106 K) also called coronal gas. Dark Nebulae Returning to our wider-angle view of the Milky Way, aside from the myriad of stars and glowing regions of gas, the most notable feature is the dark regions that blocking light from the stars beyond. These regions have historically been called dark nebulae. The question is what is the composition of these nebulae and how to they affect starlight. Interstellar Extinction The general affect of opacity is a reduction in the flux determined by the optical depth. −τ F = F0 e where for simplicity τ ≈ nσr ≈ κρr Observationally, this affects the apparent magnitude. −τ mobs = C − 2.5 log F = C − 2.5 log F0 − 2.5 log (e ) = m0 + 2.5τlog(e) = m0 + 1.086τ ≡ m0 + A The extinction, A, is added to the apparent magnitude and is linearly proportional to τ, A = 1.086τ. Optical Opacity A critical clue to the nature of dark nebulae is how the opacity changes as a function of wavelength. For example, Barnard 68 is far more opaque to visible light than it is to infra-red light.