2017Spring.Astronomyweek2.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring Pulsars

High-energy astrophysics Explore the PUL SAR menagerie Astronomers are discovering many strange properties of compact stellar objects called pulsars. Here’s how they fit together. by Victoria M. Kaspi f you browse through an astronomy book published 25 years ago, you’d likely assume that astronomers understood extremely dense objects called neutron stars fairly well. The spectacular Crab Nebula’s central body has been a “poster child” for these objects for years. This specific neutron star is a pulsar that I rotates roughly 30 times per second, emitting regular appar- ent pulsations in Earth’s direction through a sort of “light- house” effect as the star rotates. While these textbook descriptions aren’t incorrect, research over roughly the past decade has shown that the picture they portray is fundamentally incomplete. Astrono- mers know that the simple scenario where neutron stars are all born “Crab-like” is not true. Experts in the field could not have imagined the variety of neutron stars they’ve recently observed. We’ve found that bizarre objects repre- sent a significant fraction of the neutron star population. With names like magnetars, anomalous X-ray pulsars, soft gamma repeaters, rotating radio transients, and compact Long the pulsar poster child, central objects, these bodies bear properties radically differ- the Crab Nebula’s central object is a fast-spinning neutron star ent from those of the Crab pulsar. Just how large a fraction that emits jets of radiation at its they represent is still hotly debated, but it’s at least 10 per- magnetic axis. Astronomers cent and maybe even the majority. -

Planetary Nebulae Jacob Arnold AY230, Fall 2008

Jacob Arnold Planetary Nebulae Jacob Arnold AY230, Fall 2008 1 PNe Formation Low mass stars (less than 8 M) will travel through the asymptotic giant branch (AGB) of the familiar HR-diagram. During this stage of evolution, energy generation is primarily relegated to a shell of helium just outside of the carbon-oxygen core. This thin shell of fusing He cannot expand against the outer layer of the star, and rapidly heats up while also quickly exhausting its reserves and transferring its head outwards. When the He is depleted, Hydrogen burning begins in a shell just a little farther out. Over time, helium builds up again, and very abruptly begins burning, leading to a shell-helium-flash (thermal pulse). During the thermal-pulse AGB phase, this process repeats itself, leading to mass loss at the extended outer envelope of the star. The pulsations extend the outer layers of the star, causing the temperature to drop below the condensation temperature for grain formation (Zijlstra 2006). Grains are driven off the star by radiation pressure, bringing gas with them through collisions. The mass loss from pulsating AGB stars is oftentimes referred to as a wind. For AGB stars, the surface gravity of the star is quite low, and wind speeds of ~10 km/s are more than sufficient to drive off mass. At some point, a super wind develops that removes the envelope entirely, a phenomenon not yet fully understood (Bernard-Salas 2003). The central, primarily carbon-oxygen core is thus exposed. These cores can have temperatures in the hundreds of thousands of Kelvin, leading to a very strong ionizing source. -

Messier Objects

Messier Objects From the Stocker Astroscience Center at Florida International University Miami Florida The Messier Project Main contributors: • Daniel Puentes • Steven Revesz • Bobby Martinez Charles Messier • Gabriel Salazar • Riya Gandhi • Dr. James Webb – Director, Stocker Astroscience center • All images reduced and combined using MIRA image processing software. (Mirametrics) What are Messier Objects? • Messier objects are a list of astronomical sources compiled by Charles Messier, an 18th and early 19th century astronomer. He created a list of distracting objects to avoid while comet hunting. This list now contains over 110 objects, many of which are the most famous astronomical bodies known. The list contains planetary nebula, star clusters, and other galaxies. - Bobby Martinez The Telescope The telescope used to take these images is an Astronomical Consultants and Equipment (ACE) 24- inch (0.61-meter) Ritchey-Chretien reflecting telescope. It has a focal ratio of F6.2 and is supported on a structure independent of the building that houses it. It is equipped with a Finger Lakes 1kx1k CCD camera cooled to -30o C at the Cassegrain focus. It is equipped with dual filter wheels, the first containing UBVRI scientific filters and the second RGBL color filters. Messier 1 Found 6,500 light years away in the constellation of Taurus, the Crab Nebula (known as M1) is a supernova remnant. The original supernova that formed the crab nebula was observed by Chinese, Japanese and Arab astronomers in 1054 AD as an incredibly bright “Guest star” which was visible for over twenty-two months. The supernova that produced the Crab Nebula is thought to have been an evolved star roughly ten times more massive than the Sun. -

Introduction to Astronomy from Darkness to Blazing Glory

Introduction to Astronomy From Darkness to Blazing Glory Published by JAS Educational Publications Copyright Pending 2010 JAS Educational Publications All rights reserved. Including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Second Edition Author: Jeffrey Wright Scott Photographs and Diagrams: Credit NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, USGS, NOAA, Aames Research Center JAS Educational Publications 2601 Oakdale Road, H2 P.O. Box 197 Modesto California 95355 1-888-586-6252 Website: http://.Introastro.com Printing by Minuteman Press, Berkley, California ISBN 978-0-9827200-0-4 1 Introduction to Astronomy From Darkness to Blazing Glory The moon Titan is in the forefront with the moon Tethys behind it. These are two of many of Saturn’s moons Credit: Cassini Imaging Team, ISS, JPL, ESA, NASA 2 Introduction to Astronomy Contents in Brief Chapter 1: Astronomy Basics: Pages 1 – 6 Workbook Pages 1 - 2 Chapter 2: Time: Pages 7 - 10 Workbook Pages 3 - 4 Chapter 3: Solar System Overview: Pages 11 - 14 Workbook Pages 5 - 8 Chapter 4: Our Sun: Pages 15 - 20 Workbook Pages 9 - 16 Chapter 5: The Terrestrial Planets: Page 21 - 39 Workbook Pages 17 - 36 Mercury: Pages 22 - 23 Venus: Pages 24 - 25 Earth: Pages 25 - 34 Mars: Pages 34 - 39 Chapter 6: Outer, Dwarf and Exoplanets Pages: 41-54 Workbook Pages 37 - 48 Jupiter: Pages 41 - 42 Saturn: Pages 42 - 44 Uranus: Pages 44 - 45 Neptune: Pages 45 - 46 Dwarf Planets, Plutoids and Exoplanets: Pages 47 -54 3 Chapter 7: The Moons: Pages: 55 - 66 Workbook Pages 49 - 56 Chapter 8: Rocks and Ice: -

Lecture 3 - Minimum Mass Model of Solar Nebula

Lecture 3 - Minimum mass model of solar nebula o Topics to be covered: o Composition and condensation o Surface density profile o Minimum mass of solar nebula PY4A01 Solar System Science Minimum Mass Solar Nebula (MMSN) o MMSN is not a nebula, but a protoplanetary disc. Protoplanetary disk Nebula o Gives minimum mass of solid material to build the 8 planets. PY4A01 Solar System Science Minimum mass of the solar nebula o Can make approximation of minimum amount of solar nebula material that must have been present to form planets. Know: 1. Current masses, composition, location and radii of the planets. 2. Cosmic elemental abundances. 3. Condensation temperatures of material. o Given % of material that condenses, can calculate minimum mass of original nebula from which the planets formed. • Figure from Page 115 of “Physics & Chemistry of the Solar System” by Lewis o Steps 1-8: metals & rock, steps 9-13: ices PY4A01 Solar System Science Nebula composition o Assume solar/cosmic abundances: Representative Main nebular Fraction of elements Low-T material nebular mass H, He Gas 98.4 % H2, He C, N, O Volatiles (ices) 1.2 % H2O, CH4, NH3 Si, Mg, Fe Refractories 0.3 % (metals, silicates) PY4A01 Solar System Science Minimum mass for terrestrial planets o Mercury:~5.43 g cm-3 => complete condensation of Fe (~0.285% Mnebula). 0.285% Mnebula = 100 % Mmercury => Mnebula = (100/ 0.285) Mmercury = 350 Mmercury o Venus: ~5.24 g cm-3 => condensation from Fe and silicates (~0.37% Mnebula). =>(100% / 0.37% ) Mvenus = 270 Mvenus o Earth/Mars: 0.43% of material condensed at cooler temperatures. -

![Arxiv:1904.06897V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 15 Apr 2019](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4180/arxiv-1904-06897v1-astro-ph-sr-15-apr-2019-384180.webp)

Arxiv:1904.06897V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 15 Apr 2019

MNRAS 000,1–16 (2019) Preprint 16 April 2019 Compiled using MNRAS LATEX style file v3.0 The Sejong Open cluster Survey (SOS) VI. A small star-forming region in the high Galactic latitude molecular cloud MBM 110 Hwankyung Sung1?, Michael S. Bessell2, Inseok Song3 1Department of Physics and Astronomy, Sejong University, 209 Neungdong-ro, Gwangjin-gu, Seoul 05006, Korea 2Research School of Astronomy & Astrophysics, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2611, Australia 3Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA Last updated 2019 March 25 ABSTRACT We present optical photometric, spectroscopic data for the stars in the high Galactic latitude molecular cloud MBM 110. For the complete membership selection of MBM 110, we also analyze WISE mid-infrared data and Gaia astrometric data. Membership of individual stars is critically evaluated using the data mentioned above. The Gaia parallax of stars in MBM 110 is 2.667 ± 0.095 mas (d = 375 ± 13pc), which confirms that MBM 110 is a small star-forming region in the Orion-Eridanus superbubble. The age of MBM 110 is between 1.9 Myr and 3.1 Myr depending on the adopted pre-main sequence evolution model. The total stellar mass of MBM 110 is between 16 M (members only) and 23 M (including probable members). The star formation efficiency is estimated to be about 1.4%. We discuss the importance of such small star formation regions in the context of the global star formation rate and suggest that a galaxy’s star formation rate calculated from the Hα luminosity may underestimate the actual star formation rate. -

The MUSE View of the Planetary Nebula NGC 3132? Ana Monreal-Ibero1,2 and Jeremy R

A&A 634, A47 (2020) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201936845 & © ESO 2020 Astrophysics The MUSE view of the planetary nebula NGC 3132? Ana Monreal-Ibero1,2 and Jeremy R. Walsh3,?? 1 Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias (IAC), 38205 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain e-mail: [email protected] 2 Universidad de La Laguna, Dpto. Astrofísica, 38206 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 3 European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild Strasse 2, 85748 Garching, Germany Received 4 October 2019 / Accepted 6 December 2019 ABSTRACT Aims. Two-dimensional spectroscopic data for the whole extent of the NGC 3132 planetary nebula have been obtained. We deliver a reduced data-cube and high-quality maps on a spaxel-by-spaxel basis for the many emission lines falling within the Multi-Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE) spectral coverage over a range in surface brightness >1000. Physical diagnostics derived from the emission line images, opening up a variety of scientific applications, are discussed. Methods. Data were obtained during MUSE commissioning on the European Southern Observatory (ESO) Very Large Telescope and reduced with the standard ESO pipeline. Emission lines were fitted by Gaussian profiles. The dust extinction, electron densities, and temperatures of the ionised gas and abundances were determined using Python and PyNeb routines. 2 Results. The delivered datacube has a spatial size of 6300 12300, corresponding to 0:26 0:51 pc for the adopted distance, and ∼ × ∼ 1 × a contiguous wavelength coverage of 4750–9300 Å at a spectral sampling of 1.25 Å pix− . The nebula presents a complex reddening structure with high values (c(Hβ) 0:4) at the rim. -

Planetary Nebula Associations with Star Clusters in the Andromeda Galaxy Yasmine Kahvaz [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Planetary Nebula Associations with Star Clusters in the Andromeda Galaxy Yasmine Kahvaz [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Stars, Interstellar Medium and the Galaxy Commons Recommended Citation Kahvaz, Yasmine, "Planetary Nebula Associations with Star Clusters in the Andromeda Galaxy" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. 1052. http://mds.marshall.edu/etd/1052 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. PLANETARY NEBULA ASSOCIATIONS WITH STAR CLUSTERS IN THE ANDROMEDA GALAXY A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Physical and Applied Science in Physics by Yasmine Kahvaz Approved by Dr. Timothy Hamilton, Committee Chairperson Dr. Maria Babiuc Hamilton Dr. Ralph Oberly Marshall University Dec 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Timothy Hamilton at Shawnee State University, for his guidance, advice and support for all the aspects of this project. My committee, including Dr. Timothy Hamilton, Dr. Maria Babiuc Hamilton, and Dr. Ralph Oberly, provided a review of this thesis. This research has made use of the following databases: The Local Group Survey (low- ell.edu/users/massey/lgsurvey.html) and the PHAT Survey (archive.stsci.edu/prepds/phat/). I would also like to thank the entire faculty of the Physics Department of Marshall University for being there for me every step of the way through my undergrad and graduate degree years. -

Emission Nebulae

PART 3 Galaxies Gas, Stars and stellar motion in the “Milky Way” The Interstellar Medium The Sombrero Galaxy • Space is far from empty! • This dust can obscure visible light – Clouds of cold gas from stars and appear to be vast – Clouds of dust tracts of empty space • In a galaxy, gravity pulls the dust • Fortunately, it doesn’t hide all into a disk along and within the galactic plane wavelengths of light! Emission Nebulae • We frequently see nebulae (clouds of interstellar gas and dust) glowing faintly with a red or pink color • Ultraviolet radiation from nearby hot stars heats the nebula, causing it to emit photons • This is an emission nebula! Reflection Nebulae • When the cloud of gas and dust is simply illuminated by nearby stars, the light reflects, creating a reflection nebula • Typically glows blue Dark Nebulae • Nebulae that are not illuminated or heated by nearby stars are opaque – they block most of the visible light passing through it. • This is a dark nebula Interstellar Reddening • As starlight passes through a dust cloud, the dust particles scatter blue photons, allowing red photons to pass through easily • The star appears red (reddening) – it looks older and dimmer (extinction) than it really is. If one region of the sky shows nearby stars but no distant stars or galaxies, our view is probably blocked by a) nothing, but directed toward a particularly empty region of space. b) an emission nebula of ionized gas. c) an interstellar gas and dust cloud. d) a concentration of dark matter. Rotation in the Milky Way • The Milky Way does not rotate like a solid disk! – Inner parts rotate about the center faster than outer parts – Similar to the way planets rotate around the Sun – This is called differential rotation. -

Size and Scale Attendance Quiz II

Size and Scale Attendance Quiz II Are you here today? Here! (a) yes (b) no (c) are we still here? Today’s Topics • “How do we know?” exercise • Size and Scale • What is the Universe made of? • How big are these things? • How do they compare to each other? • How can we organize objects to make sense of them? What is the Universe made of? Stars • Stars make up the vast majority of the visible mass of the Universe • A star is a large, glowing ball of gas that generates heat and light through nuclear fusion • Our Sun is a star Planets • According to the IAU, a planet is an object that 1. orbits a star 2. has sufficient self-gravity to make it round 3. has a mass below the minimum mass to trigger nuclear fusion 4. has cleared the neighborhood around its orbit • A dwarf planet (such as Pluto) fulfills all these definitions except 4 • Planets shine by reflected light • Planets may be rocky, icy, or gaseous in composition. Moons, Asteroids, and Comets • Moons (or satellites) are objects that orbit a planet • An asteroid is a relatively small and rocky object that orbits a star • A comet is a relatively small and icy object that orbits a star Solar (Star) System • A solar (star) system consists of a star and all the material that orbits it, including its planets and their moons Star Clusters • Most stars are found in clusters; there are two main types • Open clusters consist of a few thousand stars and are young (1-10 million years old) • Globular clusters are denser collections of 10s-100s of thousand stars, and are older (10-14 billion years -

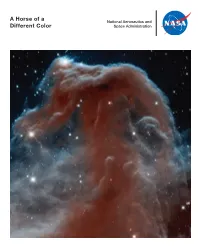

A Horse of a Different Color

A Horse of a National Aeronautics and Different Color Space Administration A Horse of a Different Color To celebrate the 23rd anniversary of the Hubble Space Telescope, NASA released a new view of the Horsehead Nebula that provides an intriguing astronomical variation on the phrase, “a horse of a different color.” The Horsehead Nebula, also known as Barnard 33, was first recorded in 1888 by Williamina Fleming at the Harvard College Observatory. Visible-light images show a black silhouette, a “dark nebula,” that resembles a horse’s head. Dark nebulae are generally most noticeable because they block the light from background stars. Two views of Horsehead Nebula To see deeper into dark nebulae, astronomers use infrared These two images reveal different views of the Horsehead Nebula. The visible-light image on the left was taken by a ground-based light. Hubble’s infrared image of the Horsehead transforms telescope. The near-infrared image on the right was taken by the the dark nebula into a softly glowing landscape. The image Hubble Space Telescope. reveals more structure and detail in the clouds. In the image at left, the gas around the Horsehead Nebula shines Many parts of the Horsehead Nebula are still opaque at infrared a bright pink, in contrast to the darkness of the Horsehead itself. This pink glow occurs along the edge of the dark cloud and is wavelengths, showing that the gas is dense and cold. Within created by the bright star, Sigma Orionis, above the Horsehead, such cold and dense clouds are regions where stars are born. -

Optical and UV Surface Brightness of Translucent Dark Nebulae ? Dust Albedo, Radiation field, and fluorescence Emission by H2 K

A&A 617, A42 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201833196 Astronomy & © ESO 2018 Astrophysics Optical and UV surface brightness of translucent dark nebulae ? Dust albedo, radiation field, and fluorescence emission by H2 K. Mattila1, M. Haas2, L. K. Haikala3, Y-S. Jo4, K. Lehtinen1,8, Ch. Leinert5, and P. Väisänen6,7 1 Department of Physics, University of Helsinki, PO Box 64, 00014 Helsinki, Finland e-mail: [email protected] 2 Astronomisches Institut, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Universitätsstrasse 150, 44801 Bochum, Germany 3 Instituto de Astronomía y Ciencias Planetarias de Atacama, Universidad de Atacama, Copayapu 485, Copiapo, Chile 4 Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute (KASI), 776 Daedeokdae-ro, Yuseong-gu, Daejeon 305-348, Korea 5 Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie, Königstuhl 17, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany 6 South African Astronomical Observatory, PO Box 9 Observatory, Cape Town, South Africa 7 Southern African Large Telescope, PO Box 9 Observatory, Cape Town, South Africa 8 Finnish Geospatial Research Institute FGI, Geodeetinrinne 2, 02430 Masala, Finland Received 9 April 2018 / Accepted 27 May 2018 ABSTRACT Context. Dark nebulae display a surface brightness because dust grains scatter light of the general interstellar radiation field (ISRF). High-galactic-latitudes dark nebulae are seen as bright nebulae when surrounded by transparent areas which have less scattered light from the general galactic dust layer. Aims. Photometry of the bright dark nebulae LDN 1780, LDN 1642, and LBN 406 shall be used to derive scattering properties of dust and to investigate the presence of UV fluorescence emission by molecular hydrogen and the extended red emission (ERE).