The Development of Th L F Th D L T F the Development of the Public-Private Partnership Technique Th Bl H T H Th P Bli I T P T Hi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

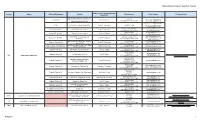

FOI Manuals/Receiving Officers Database

National Government Agencies (NGAs) Name of FOI Receiving Officer and Acronym Agency Office/Unit/Department Address Telephone nos. Email Address FOI Manuals Link Designation G/F DA Bldg. Agriculture and Fisheries 9204080 [email protected] Central Office Information Division (AFID), Elliptical Cheryl C. Suarez (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 2158 [email protected] Road, Diliman, Quezon City [email protected] CAR BPI Complex, Guisad, Baguio City Robert L. Domoguen (074) 422-5795 [email protected] [email protected] (072) 242-1045 888-0341 [email protected] Regional Field Unit I San Fernando City, La Union Gloria C. Parong (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4111 [email protected] (078) 304-0562 [email protected] Regional Field Unit II Tuguegarao City, Cagayan Hector U. Tabbun (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4209 [email protected] [email protected] Berzon Bldg., San Fernando City, (045) 961-1209 961-3472 Regional Field Unit III Felicito B. Espiritu Jr. [email protected] Pampanga (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4309 [email protected] BPI Compound, Visayas Ave., Diliman, (632) 928-6485 [email protected] Regional Field Unit IVA Patria T. Bulanhagui Quezon City (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4429 [email protected] Agricultural Training Institute (ATI) Bldg., (632) 920-2044 Regional Field Unit MIMAROPA Clariza M. San Felipe [email protected] Diliman, Quezon City (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4408 (054) 475-5113 [email protected] Regional Field Unit V San Agustin, Pili, Camarines Sur Emily B. Bordado (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4505 [email protected] (033) 337-9092 [email protected] Regional Field Unit VI Port San Pedro, Iloilo City Juvy S. -

MMARAS Annual Report 2006

MMARAS Metro Manila Accident Reporting and Analysis System Annual Report January to December 2006 Produced by the Road Safety Unit (RSU) Traffic Operations Center (TOC) Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA) 1 Introduction The Metro Manila Accident Reporting and Analysis System (MMARAS) is operated by the Road Safety Unit (RSU) of the MMDA-Traffic Operations Center (TOC), with the cooperation and assistance of the Traffic Enforcement Group under National Capital Regional Police Office (TEG-NCRPO) Philippine National Police (PNP). The objective is to compile and maintain an ongoing database of „Fatal‟ and „Non Fatal‟ including the „Damage to Property‟ road accidents, which can indicate areas where safety improvements need to be made. The system will also allow the impact of improvement measures to be monitored. This report is intended to be an annual analysis of „Fatal‟, “Non Fatal‟ and „Damage to Property‟ road accidents that have been recorded by the PNP Traffic Accident Investigators for the year 2006. The information is presented in graphical and tabular form, which provides a readily identifiable pattern of accident locations and causation patterns. Annual comparisons of traffic accident statistics are also included in this report. The Road Safety Unit currently has 9 data researchers who gather traffic accident data from different traffic offices and stations of the Traffic Enforcement Group (TEG-NCRPO) within Metro Manila. Previously, only those incidences involving Fatal and Non Fatal are gathered and encoded at the MMARAS database. But for the year 2005 up to present, we included the Damage to Property incidence so that we can see the significance and the real picture of what really is happening in our roads and also it gives us additional information in analyzing the causes of accident. -

Chapter 5 Project Scope of Work

CHAPTER 5 PROJECT SCOPE OF WORK CHAPTER 5 PROJECT SCOPE OF WORK 5.1 MINIMUM EXPRESSWAY CONFIGURATION 5.1.1 Project Component of the Project The project is implemented under the Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Scheme in accordance with the Philippine BOT Law (R.A. 7718) and its Implementing Rules and Regulations. The project is composed of the following components; Component 1: Maintenance of Phase I facility for the period from the signing of Toll Concession Agreements (TCA) to Issuance of Toll Operation Certificate (TOC) Component 2: Design, Finance with Government Financial Support (GFS), Build and Transfer of Phase II facility and Necessary Repair/Improvement of Phase I facility. Component 3: Operation and Maintenance of Phase I and Phase II facilities. 5.1.2 Minimum Expressway Configuration of Phase II 1) Expressway Alignment Phase II starts at the end point of Phase I (Coordinate: North = 1605866.31486, East 502268.99378), runs over Sales Avenue, Andrews Avenue, Domestic Road, NAIA (MIA) Road and ends at Roxas Boulevard/Manila-Cavite Coastal Expressway (see Figure 5.1.2-1). 2) Ramp Layout Five (5) new on-ramps and five 5) new off-ramps and one (1) existing off-ramp are provided as shown in Figure 5.1.2-1. One (1) on-ramp constructed under Phase I is removed. One (1) overloaded truck/Emergency Exit is provided. One (1) on-ramp for NAIA Terminal III exit traffic and one existing off-ramp from Skyway for access to NAIA Terminal III. One (1) on-ramp along Andrews Ave. to collect traffic jam from NAIA Terminal III traffic and traffic on Andrews Ave. -

Urban Transportation in Metropolitan Manila*

PHILIPPINE PLANNING JOURNAL I~ <1&~'V ..." z (/) ~ SCHOOL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL PLANNING • VOL. XVII, NO.1, OCTOBER 1985 • THE METRORAIL SYSTEM PHILIPPINE PLANNING JOURNAL VOL. XVII, No.1, Oct. 1985 Board of Editors Dolores A. Endriga Tito C. Firmalino Jaime U. Nierras Managing Editor Production Manager Carmelita R. E. U. Liwag Delia R. Alcalde Circulation & Business Manager Emily M. Mateo The Philippine Planning Journal is published in October and April by the School of Urban and Regional Planning, University of the Philippines. Views and opinions expressed in signed articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the School of Urban and Regional Planning. All communications should be addressed to the Business Manager, Philippine Planning Journal, School of Urban & Regional Planning, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines 1101. Annual Subscription Rate: Domestic, fl40.00; Foreiqn, $12.00. Single copies: Domestic, "20.00; Foreign, $6.00. Back issues: Domestic, fl10.00/issue; Foreign, $6.00Iissue. TABLE OF CONTENTS Urban Tansportation in Metropolitan Manila Selected Officials of the Ministry of Trans portation and Communications 20 Pedestrianization of a City Core and the Light Rail Transit Victoria Aureus-Eugenio 33 The LRT as a Component of Metro Manila's Trans port Systems - Ministry of Transport and Communications 46 Urban Land Management Study: Urban Redevelop ment in Connection with Metrorail Office of the Commissioner for Planning, Metro Manila Commission 57 Philippine Planning -

JEEP Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

JEEP bus time schedule & line map JEEP Aurora Blvd, Quezon City, Manila →Radial Road View In Website Mode 10 / Moriones Intersection, Manila The JEEP bus line (Aurora Blvd, Quezon City, Manila →Radial Road 10 / Moriones Intersection, Manila) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Aurora Blvd, Quezon City, Manila →Radial Road 10 / Moriones Intersection, Manila: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM (2) Radial Road 10 / Moriones Intersection, Manila →Aurora Blvd, Quezon City, Manila: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest JEEP bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next JEEP bus arriving. Direction: Aurora Blvd, Quezon City, JEEP bus Time Schedule Manila →Radial Road 10 / Moriones Intersection, Aurora Blvd, Quezon City, Manila →Radial Road 10 / Manila Moriones Intersection, Manila Route Timetable: 38 stops Sunday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Monday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Aurora Blvd, Quezon City, Manila Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM General Romulo Ave / Aurora Blvd Intersection, Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Quezon City, Manila Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Aurora Blvd / General Aguinaldo Ave Intersection, Friday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Quezon City, Manila Saturday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM Aurora Blvd / Epifanio De Los Santos Avenue Intersection, Quezon City, Manila U-Turn Slot, Philippines Aurora Blvd / N Domingo Intersection, Quezon JEEP bus Info City, Manila Direction: Aurora Blvd, Quezon City, Manila →Radial Road 10 / Moriones Intersection, Manila Aurora Blvd / Betty Go-Belmonte Intersection, Stops: 38 Quezon City, Manila Trip Duration: 65 min 760 Aurora Boulevard, Philippines Line Summary: Aurora Blvd, Quezon City, Manila, General Romulo Ave / Aurora Blvd Intersection, Saint Paul University Of Quezon City, Aurora Quezon City, Manila, Aurora Blvd / General Aguinaldo Boulevard Cor. -

Spatial Characterization of Black Carbon Mass Concentration in the Atmosphere of a Southeast Asian Megacity: an Air Quality Case Study for Metro Manila, Philippines

Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 18: 2301–2317, 2018 Copyright © Taiwan Association for Aerosol Research ISSN: 1680-8584 print / 2071-1409 online doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2017.08.0281 Spatial Characterization of Black Carbon Mass Concentration in the Atmosphere of a Southeast Asian Megacity: An Air Quality Case Study for Metro Manila, Philippines Honey Dawn Alas1,2*, Thomas Müller1, Wolfram Birmili1,6, Simonas Kecorius1, Maria Obiminda Cambaliza2,3, James Bernard B. Simpas2,3, Mylene Cayetano4, Kay Weinhold1, Edgar Vallar5, Maria Cecilia Galvez5, Alfred Wiedensohler1 1 Leibniz Institute for Tropospheric Research, 04318 Leipzig, Germany 2 The Manila Observatory, Quezon City 1101, Philippines 3 Department of Physics, Ateneo de Manila University, Quezon City 1108, Philippines 4 Institute of Environmental Science and Meteorology, University of the Philippines, Quezon City 1101, Philippines 5 Applied Research for Community, Health and Environment Resilience and Sustainability (ARCHERS), De La Salle University, Manila 1004, Philippines 6 Federal Environment Agency, 14195 Berlin, Germany ABSTRACT Black carbon (BC) particles have gathered worldwide attention due to their impacts on climate and adverse health effects on humans in heavily polluted environments. Such is the case in megacities of developing and emerging countries in Southeast Asia, in which rapid urbanization, vehicles of obsolete technology, outdated air quality legislations, and crumbling infrastructure lead to poor air quality. However, since measurements of BC are generally not mandatory, its spatial and temporal characteristics, especially in developing megacities, are poorly understood. To raise awareness on the urgency of monitoring and mitigating the air quality crises in megacities, we present the results of the first intensive characterization experiment in Metro Manila, Philippines, focusing on the spatial and diurnal variability of equivalent BC (eBC). -

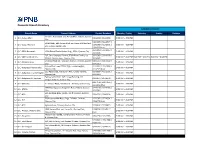

Domestic Branch Directory BANKING SCHEDULE

Domestic Branch Directory BANKING SCHEDULE Branch Name Present Address Contact Numbers Monday - Friday Saturday Sunday Holidays cor Gen. Araneta St. and Aurora Blvd., Cubao, Quezon 1 Q.C.-Cubao Main 911-2916 / 912-1938 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM City 912-3070 / 912-2577 / SRMC Bldg., 901 Aurora Blvd. cor Harvard & Stanford 2 Q.C.-Cubao-Harvard 913-1068 / 912-2571 / 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Sts., Cubao, Quezon City 913-4503 (fax) 332-3014 / 332-3067 / 3 Q.C.-EDSA Roosevelt 1024 Global Trade Center Bldg., EDSA, Quezon City 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 332-4446 G/F, One Cyberpod Centris, EDSA Eton Centris, cor. 332-5368 / 332-6258 / 4 Q.C.-EDSA-Eton Centris 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM EDSA & Quezon Ave., Quezon City 332-6665 Elliptical Road cor. Kalayaan Avenue, Diliman, Quezon 920-3353 / 924-2660 / 5 Q.C.-Elliptical Road 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM City 924-2663 Aurora Blvd., near PSBA, Brgy. Loyola Heights, 421-2331 / 421-2330 / 6 Q.C.-Katipunan-Aurora Blvd. 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Quezon City 421-2329 (fax) 335 Agcor Bldg., Katipunan Ave., Loyola Heights, 929-8814 / 433-2021 / 7 Q.C.-Katipunan-Loyola Heights 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Quezon City 433-2022 February 07, 2014 : G/F, Linear Building, 142 8 Q.C.-Katipunan-St. Ignatius 912-8077 / 912-8078 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Katipunan Road, Quezon City 920-7158 / 920-7165 / 9 Q.C.-Matalino 21 Tempus Bldg., Matalino St., Diliman, Quezon City 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 924-8919 (fax) MWSS Compound, Katipunan Road, Balara, Quezon 927-5443 / 922-3765 / 10 Q.C.-MWSS 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM City 922-3764 SRA Building, Brgy. -

Battling Congestion in Manila: the Edsa Problem

Transport and Communications Bulletin for Asia and the Pacific No. 82, 2013 BATTLING CONGESTION IN MANILA: THE EDSA PROBLEM Yves Boquet ABSTRACT The urban density of Manila, the capital of the Philippines, is one the highest of the world and the rate of motorization far exceeds the street capacity to handle traffic. The setting of the city between Manila Bay to the West and Laguna de Bay to the South limits the opportunities to spread traffic from the south on many axes of circulation. Built in the 1940’s, the circumferential highway EDSA, named after historian Epifanio de los Santos, seems permanently clogged by traffic, even if the newer C-5 beltway tries to provide some relief. Among the causes of EDSA perennial difficulties, one of the major factors is the concentration of major shopping malls and business districts alongside its course. A second major problem is the high number of bus terminals, particularly in the Cubao area, which provide interregional service from the capital area but add to the volume of traffic. While authorities have banned jeepneys and trisikel from using most of EDSA, this has meant that there is a concentration of these vehicles on side streets, blocking the smooth exit of cars. The current paper explores some of the policy options which may be considered to tackle congestion on EDSA . INTRODUCTION Manila1 is one of the Asian megacities suffering from the many ills of excessive street traffic. In the last three decades, these cities have experienced an extraordinary increase in the number of vehicles plying their streets, while at the same time they have sprawled into adjacent areas forming vast megalopolises, with their skyline pushed upwards with the construction of many high-rises. -

Philippines Claveria Laoag Aparri

Basco Philippines Claveria Laoag Aparri Vigan Tuguegarao Bauang Bontoc Palanan 바기오 Lagawe Isabela Baguio Cabarroguis Bolinao San Jose Tarlac Baler Iba 필리핀 Quezon Balanga 메트로폴리탄 마닐라 7천 1백여 개의 섬으로 이루어진 섬나라 필리핀 Metropolitan Manila Nay Pyi Taw Cavite Santa Cruz 은 크게 북부의 루손 섬, 중부의 비사얀 제도, 남 Tagaytay Daet 부 민다나오 섬 등으로 구성되어 있다. 아세안에 San Pablo Plaridel Sipocot 서는 보기 드문 가톨릭 국가로 필리핀 전역에서 아름다운 성당과 유럽식 Irga Virac Mamburao Calapan 교회를 볼 수 있다. 필리핀 경제 정치의 중심인 수도 메트로 마닐라를 비 Sorsogon 롯해 보라카이, 세부 등 세계적인 휴양지와 훼손되지 않은 자연 환경을 갖 Matnog 만달레이보라카이 San Jose 춰 최고의 여행지로 손색없는 곳이다. MandalayBoracay Masbate Catarman Philippines Kalibo Danao Cadiz Domoco lloilo San Jose Canlaon Dumaran Visayas About 필리핀 세부 Anilao Cebu Dinagat ● 기초정보 Puerto Princesa 보홀 Surigao Bohol Tagbilarah ● 역사 Dumaguete ● 이것만은 알고가기 Butuan ● 예절 Dapitan Gingoog ● 축제 Dipolog Malaybalay ● 음식 Marawi Bislig ● 쇼핑 Pagadian Tangub Tagum ● 인접 국가에서 필리핀 들어가기 Olutanga Kidapawan Maganoy Mati ● 간단 필리핀어 Isabela ● 주요 관광지_ 메트로폴리탄 마닐라, Koronadal Jolo 보라카이, 바기오, 만달레이다바오 세부, 보홀, 다바오 MandalayDavao Jose Abad Santos Balimbing Philippines 입국 시 면세 받을 수 있는 물품의 범위_ 담배 400개비, 술 2병까지(단, 1병에 1리터 미 bout 필리핀 만). 현금 $3,000 이상 소지할 경우 세관에 신고해야 한다. A 통화_ 페소 Peso (PHP)와 보조통화 센타보 Centavos. 1페소는 100센타보이다. 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, 500, 1000페소 지폐와 5, 10페소 동전 5, 10, 25 센타보 동전이 있다. 환전_ 인천공항에서 페소 직접 환전이 가능하며 필리핀 현지 공항이나 호텔, 은행, 쇼핑센터 등에서 자 기초정보 유롭게 환전할 수 있다. (1P=약 25.55원. -

Accredited Hospitals for Cooperative Health Insurance

ACCREDITED LIST HOSPITAL ABBREVIATION/KEYWO NCR ADDRESS CONTACT PERSON CONTACT NUMBERS RD CALOOCAN Acebedo General 849 Gen. Luis Street, Tel # 02-9835363 / Tel # ACEBEDO Information Department Hospital Bagbaguin, Caloocan City 02-8064298 Tel # 02-9628021 / Tel # Nodado General Hospital NODADO CALOOCAN Area A Camarin, Caloocan City Information Department 02-9627991 LAS PIÑAS OPD Department - Tel # A. Zarate General 13-765 Atlas compond naga Virginia Tumanda - OPD 02-8746903 / A. ZARATE Hospital road,, Las Piñas Department HMO Dept. - Tel # 045- 6425606 to 12 MANDALUYONG Victor R. Potenciano Katrina De Vela - HMO Tel # 02-4649999 loc. VRP 163 EDSA, Mandaluyong City Medical Center Department 362 MANILA 667 United Nations Avenue, Rogelio T. Simbul- HMO Tel # 02-5255490 / CP # Manila Doctors Hospital MADOCS Ermita Manila Department 0917-6937243 1122 General Luna Street, Ellaine Arabia - Medical Center Manila MANILA MED CP # 0999-9988805 Ermita, Manila Information Dept. Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital (East Manila 46 P Sanchez Street Sta. Mesa, Leamen Adonis - HMO Tel # 02-7163901 / Loc. LOURDES Hospital Managers Manila Department 1427 Corp.) Dr. Charles Edward Mary Chiles General Tel # 02-7355341 / Loc. MCGH Dalupan St., Sampaloc Manila Florendo - Info Hospital 54 Department MARIKINA 49 Bayan-Bayanan Ave.Marikina Garcia General Hospital GARCIA GEN Heights, Marikina City PARAÑAQUE Tel # (02) 825-6911 to Medical Center Dr. A. Santos Ave. Sucat 15 / Tel # (02) 826-2121 MCP Aurora Gomez RN Parañaque Parañaque / Tel # (02) 826-1448 /Tel # (02) 826-6111 South Superhighway Km. 17, West Service Road, SSH, Arlene Villanueva - SSMC Tel # 02-8218453 Medical Center Parañaque City Information Dept. HMO Department - Tel # Jenny Mendoza - HMO Unihealth Parañaque 02-5538809 / CP # 0933- Dr A. -

JEEP Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

JEEP bus time schedule & line map Claro M. Recto Ave / Quezon Blvd Intersection, JEEP Manila →Navotas City Hall, M. Naval, City Of View In Website Mode Navotas The JEEP bus line (Claro M. Recto Ave / Quezon Blvd Intersection, Manila →Navotas City Hall, M. Naval, City Of Navotas) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Claro M. Recto Ave / Quezon Blvd Intersection, Manila →Navotas City Hall, M. Naval, City Of Navotas: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM (2) Navotas City Hall, M. Naval, City Of Navotas →Claro M. Recto Ave / Quezon Blvd Intersection, Manila: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest JEEP bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next JEEP bus arriving. Direction: Claro M. Recto Ave / Quezon Blvd JEEP bus Time Schedule Intersection, Manila →Navotas City Hall, M. Naval, Claro M. Recto Ave / Quezon Blvd Intersection, City Of Navotas Manila →Navotas City Hall, M. Naval, City Of Navotas 46 stops Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Claro M. Recto Ave / Quezon Blvd Intersection, Manila Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Correche Underpass, Philippines Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM España Blvd / Quezon Blvd Intersection, Manila Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Quezon Blvd / P.Paredes Intersection, Manila Friday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Sulu, Manila Saturday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM Felix Huertas, Manila Felix Huertas, Manila JEEP bus Info M. Hizon, Philippines Direction: Claro M. Recto Ave / Quezon Blvd Quiricada / Felix Huertas Intersection, Manila Intersection, Manila →Navotas City Hall, M. -

1St Semester CY 2018 & Annual CY 2017

Highlights Of Accomplishment Report 1st Semester CY 2018 & Annual CY 2017 Prepared by: Corporate Planning and Management Staff Table of Contents TRAFFIC DISCIPLINE OFFICE ……………….. 1 TRAFFIC ENFORCEMENT Income from Traffic Fines Traffic Direction & Control; Metro Manila Traffic Ticketing System Commonwealth Ave./ Macapagal Ave. Speed Limit Enforement Bus Management and Dispatch System South West Integrated Provincial Transport System (SWIPTS) Bicycle-Sharing Scheme Anti-Jaywalking Operations Anti-Illegal Parking Operations Enforcement of the Yellow Lane and Closed-Door Policy Anti-Colorum and Out-of-Line Operations Operation of the TVR Redemption Facility Personnel Inspection and Monitoring Road Emergency Operations (Emergency Response and Roadside Clearing) Towing and Impounding Unified Vehicular Volume Reduction Program (UVVRP) No-Contact Apprehension Policy TRAFFIC ENGINEERING Design and Construction of Pedestrian Footbridges Traffic Survey Roadside Operation Metro Manila Accident Reporting and Analysis System (MMARAS) Application of Thermoplastic and Traffic Cold Paint Pavement Markings Upgrading of Traffic Signal System Traffic Signal Operation and Maintenance Fabrication and Manufacturing/ Maintenance of Traffic Road Signs/ Facilities TRAFFIC EDUCATION OTHER TRAFFIC IMPROVEMENT-RELATED SPECIAL PROJECTS/ MEASURES Alignment of 3 TDO Units Regulating Provincial Buses along EDSA Establish Truck Lanes along C-2 Amendment to Coverage of the “No Physical Contact Apprehension Policy” Amendments to “Light Truck”