Tnsrjournalvol4issue2finalbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Partisan Balance with Bite

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2018 Partisan Balance with Bite Daniel Hemel Brian D. Feinstein Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Daniel Hemel & Brian Feinstein, "Partisan Balance with Bite," 118 Columbia Law Review 9 (2018). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW VOL. 118 JANUARY 2018 NO. 1 ARTICLE PARTISAN BALANCE WITH BITE Brian D. Feinstein* & Daniel J. Hemel** Dozens of multimember agencies across the federal government are subject to partisan balance requirements, which mandate that no more than a simple majority of agency members may hail from a single party. Administrative law scholars and political scientists have questioned whether these provisions meaningfully affect the ideological composition of federal agencies. In theory, Presidents can comply with these require- ments by appointing ideologically sympathetic members of the opposite party once they have filled their quota of same-party appointees (i.e., a Democratic President can appoint liberal Republicans or a Republican President can appoint conservative Democrats). No multiagency study in the past fifty years, however, has examined whether—in practice— partisan balance requirements actually prevent Presidents from selecting like-minded individuals for cross-party appointments. This Article fills that gap. We gather data on 578 appointees to twenty-three agencies over the course of six presidencies and thirty-six years. -

DIRECTING the Disorder the CFR Is the Deep State Powerhouse Undoing and Remaking Our World

DEEP STATE DIRECTING THE Disorder The CFR is the Deep State powerhouse undoing and remaking our world. 2 by William F. Jasper The nationalist vs. globalist conflict is not merely an he whole world has gone insane ideological struggle between shadowy, unidentifiable and the lunatics are in charge of T the asylum. At least it looks that forces; it is a struggle with organized globalists who have way to any rational person surveying the very real, identifiable, powerful organizations and networks escalating revolutions that have engulfed the planet in the year 2020. The revolu- operating incessantly to undermine and subvert our tions to which we refer are the COVID- constitutional Republic and our Christian-style civilization. 19 revolution and the Black Lives Matter revolution, which, combined, are wreak- ing unprecedented havoc and destruction — political, social, economic, moral, and spiritual — worldwide. As we will show, these two seemingly unrelated upheavals are very closely tied together, and are but the latest and most profound manifesta- tions of a global revolutionary transfor- mation that has been under way for many years. Both of these revolutions are being stoked and orchestrated by elitist forces that intend to unmake the United States of America and extinguish liberty as we know it everywhere. In his famous “Lectures on the French Revolution,” delivered at Cambridge University between 1895 and 1899, the distinguished British historian and states- man John Emerich Dalberg, more com- monly known as Lord Acton, noted: “The appalling thing in the French Revolution is not the tumult, but the design. Through all the fire and smoke we perceive the evidence of calculating organization. -

George HW Bush and CHIREP at the UN 1970-1971

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-22-2020 The First Cut is the Deepest: George H.W. Bush and CHIREP at the U.N. 1970-1971 James W. Weber Jr. University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Asian History Commons, Cultural History Commons, Diplomatic History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Weber, James W. Jr., "The First Cut is the Deepest: George H.W. Bush and CHIREP at the U.N. 1970-1971" (2020). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 2756. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/2756 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The First Cut is the Deepest : George H.W. Bush and CHIREP at the U.N. 1970–1971 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History by James W. -

The Ineffectiveness of a Multinational Sanctions Regime Under

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 6-29-2011 The neffecI tiveness of a Multinational Sanctions Regime Under Globalization: The aC se of Iraq Manuel De Leon Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI11081006 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Recommended Citation De Leon, Manuel, "The neffeI ctiveness of a Multinational Sanctions Regime Under Globalization: The asC e of Iraq" (2011). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 463. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/463 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida THE INEFFECTIVENESS OF MULTILATERAL SANCTIONS REGIMES UNDER GLOBALIZATION: THE CASE OF IRAQ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in POLITICAL SCIENCE by Manuel De Leon 2011 To: Dean Kenneth Furton College of Arts and Sciences This dissertation, written by Manuel De Leon, and entitled The Ineffectiveness of Multilateral Sanctions Regimes Under Globalization: The Case of Iraq, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Mohiaddin Mesbahi _______________________________________ Dario Moreno _______________________________________ Astrid Arraras _______________________________________ Ronald W. Cox, Major Professor Date of Defense: June 29, 2011 The dissertation of Manuel De Leon is approved. -

Report by the Military and Veterans Affairs Committee and the Task Force on the Rule of Law Condemning Presidential Pardons of Accused and Convicted War Criminals

CONTACT POLICY DEPARTMENT ELIZABETH KOCIENDA 212.382.4788 | [email protected] MARY MARGULIS-OHNUMA 212.382.6767 | [email protected] REPORT BY THE MILITARY AND VETERANS AFFAIRS COMMITTEE AND THE TASK FORCE ON THE RULE OF LAW CONDEMNING PRESIDENTIAL PARDONS OF ACCUSED AND CONVICTED WAR CRIMINALS On May 6, 2019 and November 15, 2019, President Trump pardoned three Army officers convicted or accused of war crimes: (i) First Lieutenant (“1LT”) Michael Behanna, who was convicted of executing a prisoner he was ordered to release, (ii) 1LT Clint Lorance, who was convicted of numerous crimes, including the murder of two men his soldiers agreed posed no threat to them, and (iii) Major (“MAJ”) Mathew Golsteyn, who was about to stand trial for the murder of a suspected Taliban bombmaker he was ordered to release — and who MAJ Golsteyn repeatedly confessed to killing. The pardoning of military members convicted or accused of battlefield murders appears to be unprecedented in American history.1 These pardons were deeply opposed by many top military commanders because there was no justifiable basis for them, such as a legitimate claim of innocence.2 As former Marine Corps Commandant Charles Krulak stated before the pardons occurred, “[i]f President Trump follows through on reports that he will . pardon[] individuals accused or convicted of war crimes, he will betray [our] ideals and undermine decades of precedent in American military justice that has contributed to making our country’s fighting forces the envy of the world.”3 And as the head of U.S. Army Special Operations Command recently stated in a memo rejecting MAJ Golsteyn’s request to reinstate his Special Warfare tab, President Trump’s preemptive pardon “does not erase or expunge the record of offense charges and does not indicate [MAJ Golsteyn’s] innocence.”4 Instead, what underlies these pardons are President Trump’s misguided views that the 1 The closest example appears to be 2LT William L. -

Defense Advisory Committee on Women in the Services Articles of Interest for the Week of 20 November 2015

Defense Advisory Committee on Women in the Services Articles of Interest for the Week of 20 November 2015 RECRUITMENT & RETENTION 1. Military reports slight uptick in women joining officer corps (16 Nov) Military Times, By Andrew Tilghman The Pentagon is seeing a small rise in the percentage of women entering the officer corps, according to a report released. 2. Force of the Future Looks to Maintain U.S. Advantages (18 Nov) DoD News, Defense Media Activity, By Jim Garamone “Permeability” is a word that will be heard a lot in relation to Defense Secretary Ash Carter’s new Force of the Future program. 3. Carter Details Force of the Future Initiatives (18 Nov) DoD News, Defense Media Activity, By Jim Garamone Defense Secretary Ash Carter said his Force of the Future program is necessary to ensure the Defense Department continues to attract the best people America has to offer. 4. Pentagon to Escalate War for Talent (18 Nov) National Defense, By Sandra I. Erwin A wide-ranging personnel reform proposal unveiled by Defense Secretary Ashton Carter could put the Pentagon in a better position to compete with the private sector for talent. EMPLOYMENT & INTEGRATION 5. Grosso pins on 3rd star to become first female USAF personnel chief (16 Nov) Air Force Times, By Stephen Losey Lt. Gen. Gina Grosso, the Air Force's new personnel chief, formally pinned on her third star during a ceremony at the Pentagon Monday. 6. The Army is looking for hundreds of NCOs for drill sergeant duty (16 Nov) Army Times, By Michelle Tan The search is two-pronged: the Army needs more female drill sergeants as it prepares to open more jobs to women and tries to recruit more women into the service, while the Army Reserve only has 60 percent of the drill sergeants it needs. -

Copyright by John Michael Meyer 2020

Copyright by John Michael Meyer 2020 The Dissertation Committee for John Michael Meyer Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Dissertation. One Way to Live: Orde Wingate and the Adoption of ‘Special Forces’ Tactics and Strategies (1903-1944) Committee: Ami Pedahzur, Supervisor Zoltan D. Barany David M. Buss William Roger Louis Thomas G. Palaima Paul B. Woodruff One Way to Live: Orde Wingate and the Adoption of ‘Special Forces’ Tactics and Strategies (1903-1944) by John Michael Meyer Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2020 Dedication To Ami Pedahzur and Wm. Roger Louis who guided me on this endeavor from start to finish and To Lorna Paterson Wingate Smith. Acknowledgements Ami Pedahzur and Wm. Roger Louis have helped me immeasurably throughout my time at the University of Texas, and I wish that everyone could benefit from teachers so rigorous and open minded. I will never forget the compassion and strength that they demonstrated over the course of this project. Zoltan Barany developed my skills as a teacher, and provided a thoughtful reading of my first peer-reviewed article. David M. Buss kept an open mind when I approached him about this interdisciplinary project, and has remained a model of patience while I worked towards its completion. My work with Tom Palaima and Paul Woodruff began with collaboration, and then moved to friendship. Inevitably, I became their student, though they had been teaching me all along. -

(Tyler) Priest

Richard (Tyler) Priest Associate Professor Departments of History and Geographical and Sustainability Sciences 280 Schaeffer Hall University of Iowa Iowa City, IA 52242 (319) 335-2096 [email protected] EDUCATIONAL AND PROFESSIONAL HISTORY 1. Education Ph.D. University of Wisconsin-Madison, History (December 1996) M.A. University of Wisconsin-Madison, History (December 1990) B.A. Carleton College, Northfield, Minnesota, History (June 1986) 2. Professional and Academic Positions 2012-present Associate Professor of History and Geographical and Sustainability Sciences, University of Iowa 2004-2012 Director of Global Studies and Clinical Professor, C.T. Bauer College of Business, University of Houston 2010-2011 Senior Policy Analyst, National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling 2002-2005 Historical Consultant, History of Offshore Oil and Gas Industry in Southern Louisiana Research Project, Minerals Management Service, 2002-2005 2000-2002 Visiting Assistant Professor, University of Houston-Clear Lake 1998-2001 Chief Historian, Shell Oil History Project 1997-1998 Postdoctoral Fellow, Center for the Americas, University of Houston 1996-1997 Researcher and Author, Brown & Root Inc. History Project on the Offshore Oil Industry 1994-1995 Visiting Instructor, Middlebury College 3. Honors and Awards Collegiate Teaching Award, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, University of Iowa, 2017 Award for Distinguished Achievement in Publicly Engaged Research, University of Iowa, 2016 Partners in Conservation Award, -

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA ISSN 0219-3213 TRS15/21s ISSUE ISBN 978-981-5011-00-5 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace 15 Singapore 119614 http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg 9 7 8 9 8 1 5 0 1 1 0 0 5 2021 21-J07781 00 Trends_2021-15 cover.indd 1 8/7/21 12:26 PM TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 1 9/7/21 8:37 AM The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (formerly Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) is an autonomous organization established in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security, and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are grouped under Regional Economic Studies (RES), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). The Institute is also home to the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC), the Singapore APEC Study Centre and the Temasek History Research Centre (THRC). ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued more than 2,000 books and journals. It is the largest scholarly publisher of research about Southeast Asia from within the region. ISEAS Publishing works with many other academic and trade publishers and distributors to disseminate important research and analyses from and about Southeast Asia to the rest of the world. 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 2 9/7/21 8:37 AM THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik ISSUE 15 2021 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 3 9/7/21 8:37 AM Published by: ISEAS Publishing 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg © 2021 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore All rights reserved. -

TNSR and Discusses the Joys and Pains of the Review Process, Giving Some Advice for Both Reviewers and Those Submitting Their Work for Review

ISSN 2576-1021 ISSN 2576-1153 Print: Online: Texas National Security Review CLARITY & QUAGMIRE Volume 2 Issue 2 MASTHEAD TABLE OF CONTENTS Staff: The Foundation Publisher: Managing Editor: 04 Reviewing Blues Ryan Evans Megan G. Oprea, PhD Assistant Editor: Francis J. Gavin Autumn Brewington Editor-in-Chief: Associate Editors: William Inboden, PhD Galen Jackson, PhD Van Jackson, PhD Stephen Tankel, PhD The Scholar 10 When Do Leaders Change Course? Theories of Success and the American Withdrawal Editorial Board: from Beirut, 1983–1984 Alexandra T. Evans and A. Bradley Potter Chair, Editorial Board: Editor-in-Chief: 40 How to Think About Nuclear Crises Francis J. Gavin, PhD William Inboden, PhD Mark S. Bell and Julia Macdonald Robert J. Art, PhD Beatrice Heuser, PhD Patrick Porter, PhD Richard Betts, PhD Michael C. Horowitz, PhD Thomas Rid, PhD John Bew, PhD Richard H. Immerman, PhD Joshua Rovner, PhD Nigel Biggar, PhD Robert Jervis, PhD Brent E. Sasley, PhD The Strategist Philip Bobbitt, JD, PhD Colin Kahl, PhD Elizabeth N. Saunders, PhD Hal Brands, PhD Jonathan Kirshner, PhD Kori Schake, PhD 68 After the Responsible Stakeholder, What? Debating America’s China Strategy Joshua W. Busby, PhD James Kraska, SJD Michael N. Schmitt, DLitt Hal Brands and Zack Cooper Robert Chesney, JD Stephen D. Krasner, PhD Jacob N. Shapiro, PhD Eliot Cohen, PhD Sarah Kreps, PhD Sandesh Sivakumaran, PhD 82 Crossroads: Counter-terrorism and the Internet Audrey Kurth Cronin, PhD Melvyn P. Leffler, PhD Sarah Snyder, PhD Brian Fishman Theo Farrell, PhD Fredrik Logevall, PhD Bartholomew Sparrow, PhD 102 The End of the End of History: Reimagining U.S. -

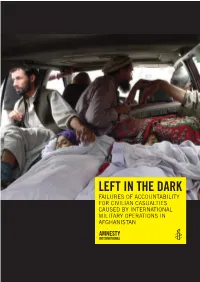

Left in the Dark

LEFT IN THE DARK FAILURES OF ACCOUNTABILITY FOR CIVILIAN CASUALTIES CAUSED BY INTERNATIONAL MILITARY OPERATIONS IN AFGHANISTAN Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: ASA 11/006/2014 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Bodies of women who were killed in a September 2012 US airstrike are brought to a hospital in the Alingar district of Laghman province. © ASSOCIATED PRESS/Khalid Khan amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF AFGHANISTAN .......................................................................................... 6 1. SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 7 Methodology .......................................................................................................... -

Anti-Draft March Gets Little Support

A member of the Campus Digest News Service and the National News Bureau. VOL. XXIII, NO. 7 Atlanta, Georgia March 12, 1980 Anti-Draft March Gets Little Support By Bridgett M. Davis February 14, 1980 at Morehouse college. On Friday, February 28, 1980, The group’s orange and black the members of the Black banners read, “Stop the U.S. War Students’ Coalition of Atlanta Drive”, and “No Draft No Way”. (BSCA) sponsored a protest mar- For a while, the members patien ch/rally at the Russell Building at- tly waited to recruit interested the corner of Mitchell and Spring persons from the many passer- St. The turn-out, however, was sbys, then the fervored cries of unexpectedly low. Only a few of one enthused young man could the BSCA members themselves be heard within the immediate were initially present at the pre vicinity as he yelled, “Hell no! arranged starting time of three We won’t go! Hell no! We won’t o’clock. go!!!” Eventually, the small group of dedicated followers were led The BSCA was formulated by Robert Booker, a sophmore at especially for the anti-draft Morehouse, outward to Chestnut issue.Their previous par Street where they began a small ticipation has been much more yet determined procession. In an encouraging than the turn-out for attempt to collect more the march. Their first meeting followers as tney progresses, the was held at Spelman on February marchers traveled around the en 2nd, where at least fifty in tire Atlanta University Center, terested persons attended. The but few if any joined the ban The Black Students’ Coalition of Atlanta sponsored a protest march on February 28, second meeting, which was held dwagon.