Education and Outreach: the History of Dinosaur Palaeoart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Luis V. Rey & Gondwana Studios

EXHIBITION BY LUIS V. REY & GONDWANA STUDIOS HORNS, SPIKES, QUILLS AND FEATHERS. THE SECRET IS IN THE SKIN! Not long ago, our knowledge of dinosaurs was based almost completely on the assumptions we made from their internal body structure. Bones and possible muscle and tendon attachments were what scientists used mostly for reconstructing their anatomy. The rest, including the colours, were left to the imagination… and needless to say the skins were lizard-like and the colours grey, green and brown prevailed. We are breaking the mould with this Dinosaur runners, massive horned faces and Revolution! tank-like monsters had to live with and defend themselves against the teeth and claws of the Thanks to a vast web of new research, that this Feathery Menace... a menace that sometimes time emphasises also skin and ornaments, we reached gigantic proportions in the shape of are now able to get a glimpse of the true, bizarre Tyrannosaurus… or in the shape of outlandish, and complex nature of the evolution of the massive ornithomimids with gigantic claws Dinosauria. like the newly re-discovered Deinocheirus, reconstructed here for the first time in full. We have always known that the Dinosauria was subdivided in two main groups, according All of them are well represented and mostly to their pelvic structure: Saurischia spectacularly mounted in this exhibition. The and Ornithischia. But they had many things exhibits are backed with close-to-life-sized in common, including structures made of a murals of all the protagonist species, fully special family of fibrous proteins called keratin fleshed and feathered and restored in living and that covered their skin in the form of spikes, breathing colours. -

D Inosaur Paleobiology

Topics in Paleobiology The study of dinosaurs has been experiencing a remarkable renaissance over the past few decades. Scientifi c understanding of dinosaur anatomy, biology, and evolution has advanced to such a degree that paleontologists often know more about 100-million-year-old dinosaurs than many species of living organisms. This book provides a contemporary review of dinosaur science intended for students, researchers, and dinosaur enthusiasts. It reviews the latest knowledge on dinosaur anatomy and phylogeny, Brusatte how dinosaurs functioned as living animals, and the grand narrative of dinosaur evolution across the Mesozoic. A particular focus is on the fossil evidence and explicit methods that allow paleontologists to study dinosaurs in rigorous detail. Scientifi c knowledge of dinosaur biology and evolution is shifting fast, Dinosaur and this book aims to summarize current understanding of dinosaur science in a technical, but accessible, style, supplemented with vivid photographs and illustrations. Paleobiology Dinosaur The Topics in Paleobiology Series is published in collaboration with the Palaeontological Association, Paleobiology and is edited by Professor Mike Benton, University of Bristol. Stephen Brusatte is a vertebrate paleontologist and PhD student at Columbia University and the American Museum of Natural History. His research focuses on the anatomy, systematics, and evolution of fossil vertebrates, especially theropod dinosaurs. He is particularly interested in the origin of major groups such Stephen L. Brusatte as dinosaurs, birds, and mammals. Steve is the author of over 40 research papers and three books, and his work has been profi led in The New York Times, on BBC Television and NPR, and in many other press outlets. -

Layout 1 (Page 2)

SEPTEMBER 9-15, 2011 CCURRENTSURRENTS The News-Review’s guide to arts, entertainment and television ToastToast ofof thethe towntown WinemakersWinemakers featurefeature theirtheir concoctionsconcoctions atat thethe 42nd42nd annualannual UmpquaUmpqua ValleyValley WineWine ArtArt andand MusicMusic FestivalFestival MICHAEL SULLIVAN/The News-Review INSIDE: What’s Happening/3 Calendar/4 Book Review/10 Movie Review/14 TV/15 Page 2, The News-Review Roseburg, Oregon, Currents—Thursday, September 8, 2011 * &YJUt$BOZPOWJMMF 03t*OGPt3FTtTFWFOGFBUIFSTDPN Roseburg, Oregon, Currents—Thursday, September 8, 2011 The News-Review, Page 3 what’s HAPPENING TENMILE An artists’ reception will be held from 5 to 7 p.m. Friday at Remembering GEM GLAM the gallery, 638 W. Harrison St., Roseburg. 9/11 movie, songs Also hanging is art by pastel A special 9/11 remembrance painter Phil Bates, mixed event will be held at 5 p.m. media artist Jon Leach and Sunday at the Tenmile Com- acrylic painter Holly Werner. munity United Methodist Fisher’s is open regularly Church, 2119 Tenmile Valley from 9 to 5 p.m. Monday Road. through Friday. The event includes a show- Information: 541-817-4931. ing of a one-hour movie, “The Cross and the Towers,” fol- lowed by patriotic music and MYRTLE CREEK sing-alongs with musicians Mark Baratta and Scott Van Local artist’s work Atta. hangs at gallery The event is free, but dona- Myrtle Creek artist Darlene tions for musicians’ expenses Musgrave is the featured artist are welcome. Refreshments at Ye Olde Art Shoppe. will be served. An artist’s reception for Information: 541-643-1636. Musgrave will be held from 10 a.m. -

R~;: PHYSIOLOGICAL, MIGRATORIAL

....----------- 'r~;: i ! 'r; Pa/eont .. 62(4), 1988, pp. 64~52 Copyright © 1988, The Paleontological Society 0022-3360/88/0062-0640$03.00 PHYSIOLOGICAL, MIGRATORIAL, CLIMATOLOGICAL, GEOPHYSICAL, SURVIVAL, AND EVOLUTIONARY IMPLICATIONS OF CRETACEOUS POLAR DINOSAURS GREGORY S. PAUL 3109 North Calvert Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21218 ABSTRACTT- he presence of Late Cretaceous social dinosaurs in polar regions confronted them with winter conditions of extended dark, coolness, breezes, and precipitation that could best be coped with via an endothermic homeothermic physiology of at least the tenrec level. This is true whether the dinosaurs stayed year round in the polar regime-which in North America extended from Alaska south to Montana-or if they migrated away from polar winters. More reptilian physiologies fail to meet the demands of such winters -in certain key ways, a· point tentatively confirmed by the apparent failure of giant Late Cretaceous phobosuchid crocodilians to dwell north of Montana. Low metabolisms were also insufficient for extended annual migrations away from and towards the poles. It is shown that even high metabolic rate dinosaurs probably remained in their polar habitats year-round. The possibility that dinosaurs had avian-mammalian metabolic systems, and may have borne insulation at least seasonally, severely limits their use as polar paleoclimatic and Earth axial tilt indicators. Polar dinosaurs may have been a center of dinosaur evolution. The possible ability of polar dinosaurs to cope with conditions of cool and dark challenges theories that a gradual temperature decline, or a sudden, meteoritic or volcanic induced collapse in temperature and sunlight, destroyed the dinosaurs. INTRODUCTION America suggests that dinosaurs were regularly crossing, and NCREASINGNUMBERSof remains show that dinosaurs lived living upon, the Bering Land Bridge within a few degrees of the I near the North and South Poles during the Cretaceous. -

State of the Palaeoart

Palaeontologia Electronica http://palaeo-electronica.org State of the Palaeoart Mark P. Witton, Darren Naish, and John Conway The discipline of palaeoart, a branch of natural history art dedicated to the recon- struction of extinct life, is an established and important component of palaeontological science and outreach. For more than 200 years, palaeoartistry has worked closely with palaeontological science and has always been integral to the enduring popularity of prehistoric animals with the public. Indeed, the perceived value or success of such products as popular books, movies, documentaries, and museum installations can often be linked to the quality and panache of its palaeoart more than anything else. For all its significance, the palaeoart industry ment part of this dialogue in the published is often poorly treated by the academic, media and literature, in turn bringing the issues concerned to educational industries associated with it. Many wider attention. We argue that palaeoartistry is standard practises associated with palaeoart pro- both scientifically and culturally significant, and that duction are ethically and legally problematic, stifle improved working practises are required by those its scientific and cultural growth, and have a nega- involved in its production. We hope that our views tive impact on the financial viability of its creators. inspire discussion and changes sorely needed to These issues create a climate that obscures the improve the economy, quality and reputation of the many positive contributions made by palaeoartists palaeoart industry and its contributors. to science and education, while promoting and The historic, scientific and economic funding derivative, inaccurate, and sometimes exe- significance of palaeoart crable artwork. -

Laurel Wilt Strikes Lake Park Bay Trees

rѮJSERVBSUFSTVSHFMJѫT8PMGQBDL PWFS7JLJOHTr-BUFTDPSJOHESJWF HJWFT&BTU#MBEFOXJOPWFS (BUPSTr-BEZ1BDLUBLFTUFOOJTWJD Sports UPSZPWFS4$)44FFQBHF# ThePublished News since 1890 every Monday and Tursday forReporter the County of Columbus and her people. Monday, August 29, 2011 Department Volume 121, Number 17 of Aging losses Whiteville, North Carolina 50 Cents exceed $800,000 nCommissioners meet Tuesday to Inside Today discuss cuts. By NICOLE CARTRETTE 4-A Staff Writer r'SPHTBZTIFXJMM TVSSFOEFSUPEBZ The Columbus County Department of Ag- ing (DOA) has yet to disclose in clear detail 9-A the circumstances surrounding what officials r$PVOUZTQSPQFSUZ reported in July as a $500,000 loss in the depart- UBYEJTDPVOUFOET ment’s in-home services division. At least one income statement from the 8FEOFTEBZ county finance office indicates that aging’s losses actually totaled $816,014, as of June 30. While the department posted revenues of more than $2.5 million, expenses totaled nearly $3.4 million. The department’s $193,314 fund balance was wiped out, leaving a new fund balance of negative $622,700, according to the income statement provided by the county. Friday, County Finance Officer Bobbie Staff photo by Les High Faircloth could not answer questions about the Whiteville resident Emory Worley works to clear debris from a tree that Hurricane Irene’s winds department’s loss but did say the department toppled onto his house. had reported new income exceeding $300,000 but it is unclear what the department’s finan- cial condition will look like in coming months Today’s as the county had made no changes at the American Profle fea- department to curb mounting losses. -

Nurse Aide Wins Battle with Snake 911 EVENT

911 EVENT *OJUTOFYUJTTVF Te r1BUSJPUTUBLFXJOPWFS8PMGQBDL r4UBMMJPOTGBMMTIPSUBU-PSJTr4DPSQJ News ReporterUBLFT POTIBOE(BUPSTUIJSETUSBJHIUMPTT BMPPLBUIPX9/11 r)PCCUPOOJQT7JLJOHTr4$)4TQJL JNQBDUFE$PMVNCVT FSTTUBZVOCFBUFOr-BEZ1BDLOFUUFST Next ISSUE $PVOUZSFTJEFOUT Sports FEHF8FTU#SVOTXJDLSee page 1-B. ThePublished News since 1890 every Monday and Tursday forReporter the County of Columbus and her people. Monday, September 5, 2011 More debt Tire company for county Volume 121, Number 19 Whiteville, North Carolina water district; may roll into 50 Cents closed session Brunswick Tuesday By NICOLE CARTRETTE County Inside Today Staff Writer 4-A By NICOLE CARTRETTE More debt for one water Staff Writer r3PCCFSZJO district and a closed session for #FBWFSEBNFBSMJFS attorney client privilege are A project code named “Project Soccer” that among a number of items on could bring as many as 1,500 to the Columbus UPEBZ the Columbus County commis- County border via the establishment of a facil- sioners’ agenda for Tuesday ity on property in Brunswick County doesn’t night. appear to be so much of a secret anymore. Commissioners regular Last week, the N.C. Rural Center earmarked meeting night (Monday) was $1.43 million toward an incentive for the un- Labor Day so the board moved disclosed company but over the weekend there its meeting to Tuesday. was a lot of talk among various media outlets The board will consider a about Continental Tire being the undisclosed resolution related to a $1.9 mil- company. lion project that will intercon- State incentives for an undisclosed com- nect Water District II to Water pany that is eyeing a more than 400 acre District I. Brunswick County site near the Columbus Several months ago com- County border could be at the forefront of missioners proposed seeking legislative talks when the N.C. -

A Bird's Eye View of the Evolution of Avialan Flight

Chapter 12 Navigating Functional Landscapes: A Bird’s Eye View of the Evolution of Avialan Flight HANS C.E. LARSSON,1 T. ALEXANDER DECECCHI,2 MICHAEL B. HABIB3 ABSTRACT One of the major challenges in attempting to parse the ecological setting for the origin of flight in Pennaraptora is determining the minimal fluid and solid biomechanical limits of gliding and powered flight present in extant forms and how these minima can be inferred from the fossil record. This is most evident when we consider the fact that the flight apparatus in extant birds is a highly integrated system with redundancies and safety factors to permit robust performance even if one or more components of their flight system are outside their optimal range. These subsystem outliers may be due to other adaptive roles, ontogenetic trajectories, or injuries that are accommodated by a robust flight system. This means that many metrics commonly used to evaluate flight ability in extant birds are likely not going to be precise in delineating flight style, ability, and usage when applied to transitional taxa. Here we build upon existing work to create a functional landscape for flight behavior based on extant observations. The functional landscape is like an evolutionary adap- tive landscape in predicting where estimated biomechanically relevant values produce functional repertoires on the landscape. The landscape provides a quantitative evaluation of biomechanical optima, thus facilitating the testing of hypotheses for the origins of complex biomechanical func- tions. Here we develop this model to explore the functional capabilities of the earliest known avialans and their sister taxa. -

Visions of the Prehistoric Past Reviewed by Mark P. Witton

Palaeontologia Electronica http://palaeo-electronica.org Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past Reviewed by Mark P. Witton Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past. 2017. Written by Zoë Lescaze and Walton Ford. Taschen. 292 pages, ISBN 978-3-8365-5511-1 (English edition). € 75, £75, $100 (hardcover) Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past is a collection of palaeoartworks spanning 150 years of palaeoart history, from 1830 to the second half of the 20th century. This huge, supremely well-pre- sented book was primarily written by journalist, archaeological illustrator and art scholar Zoë Les- caze, with an introduction by artist Walton Ford (both are American, and use ‘paleoart’ over the European spelling ‘palaeoart’). Ford states that the genesis of the book reflects “the need for a paleo- art book that was more about the art and less about the paleo” (p. 12), and thus Paleoart skews towards artistic aspects of palaeoartistry rather than palaeontological theory or technical aspects of reconstructing extinct animal appearance. Ford and Lescaze are correct that this angle of palaeo- artistry remains neglected, and this puts Paleoart in prime position to make a big impact on this pop- ular, though undeniably niche subject. Paleoart is extremely well-produced and stun- ning to look at, a visual feast for anyone with an interest in classic palaeoart. 292 pages of thick, sturdy paper (9 chapters, hundreds of images, and four fold outs) and almost impractical dimensions (28 x 37.4 cm) make it a physically imposing, stately tome that reminds us why books belong on shelves and not digital devices. Focusing exclu- sively on 2D art, the layout is minimalist and clean, detail, unobscured by text and labelling. -

Screaming Biplane Dromaeosaurs of the Air. June/July

5c.r~i~ ~l'tp.,ne pr~tl\USp.,urs 1tke.A-ir Written & illustrated by Gregory s. Paul It is questionable whether anyone even speculated that some dinosaurs were feathered until Ostrom detailed the evidence that birds descended from predatory avepod theropods a third of a century ago. The first illustration of a feathered dinosaur was a nice little study of a well ensconced Syntarsus dashing down a dune slope in pursuit of a gliding lizard in Robert Bakker's classic "Dinosaur Renaissance" article in the April 1975 Scientific American by Sarah Landry (can also be seen in the Scientific American Book of the Dinosaur I edited). My first feathered dinosaur was executed shortly after, an inappropriately shaggy Allosaurus attacking a herd of Diplodocus. I was soon doing a host of small theropods in feathers. Despite the logic of feath- / er insulation on the group ancestral birds and showing evidence of a high level energetics, images of feathered avepods were often harshly and unsci- Above: Proposed relationships based on flight adaptations of entifically criticized as unscientific in view of the lack of evidence for their preserved skeletons and feathers of Archaeopteryx, a generalized presence, ignoring the equal fact that no one had found scales on the little Sinornithosaurus, and Confuciusornis, with arrows indicating dinosaurs either. derived adaptations not present in Archaeopteryx as described in In the 1980s I further proposed that the most bird-like, avepectoran text. Not to scale. dinosaurs - dromaeosaurs, troodonts, oviraptorosaurs, and later ther- izinosaurs _were not just close to birds and the origin of flight, but were see- appear to represent the remnants of wings converted to display devices. -

(PDF) Dinosaur Art: the World's Greatest Paleoart Steve White

(PDF) Dinosaur Art: The World'S Greatest Paleoart Steve White - download pdf free book pdf free download Dinosaur Art: The World's Greatest Paleoart, Free Download Dinosaur Art: The World's Greatest Paleoart Full Popular Steve White, by Steve White pdf Dinosaur Art: The World's Greatest Paleoart, full book Dinosaur Art: The World's Greatest Paleoart, Steve White epub Dinosaur Art: The World's Greatest Paleoart, PDF Dinosaur Art: The World's Greatest Paleoart Free Download, online free Dinosaur Art: The World's Greatest Paleoart, Download Dinosaur Art: The World's Greatest Paleoart PDF, Download Dinosaur Art: The World's Greatest Paleoart E-Books, Dinosaur Art: The World's Greatest Paleoart Ebooks, Free Download Dinosaur Art: The World's Greatest Paleoart Ebooks Steve White, Dinosaur Art: The World's Greatest Paleoart Ebooks, Read Dinosaur Art: The World's Greatest Paleoart Ebook Download, Download PDF Dinosaur Art: The World's Greatest Paleoart, Free Download Dinosaur Art: The World's Greatest Paleoart Full Version Steve White, Dinosaur Art: The World's Greatest Paleoart Full Download, by Steve White pdf Dinosaur Art: The World's Greatest Paleoart, Steve White ebook Dinosaur Art: The World's Greatest Paleoart, by Steve White pdf Dinosaur Art: The World's Greatest Paleoart, Read Dinosaur Art: The World's Greatest Paleoart Full Collection Steve White, CLICK FOR DOWNLOAD epub, mobi, pdf, kindle Description: The review included little on what I looked like and no word to say about how much that got in way of my head, only some mention from other readers those reading just knew who read The author was a real geek. -

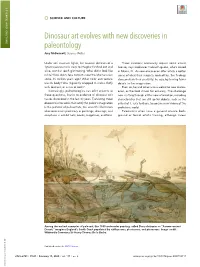

Dinosaur Art Evolves with New Discoveries in Paleontology Amy Mcdermott, Science Writer

SCIENCE AND CULTURE SCIENCE AND CULTURE Dinosaur art evolves with new discoveries in paleontology Amy McDermott, Science Writer Under soft museum lights, the massive skeleton of a Those creations necessarily require some artistic Tyrannosaurus rex is easy to imagine fleshed out and license, says freelancer Gabriel Ugueto, who’s based alive, scimitar teeth glimmering. What did it look like in Miami, FL. As new discoveries offer artists a better in life? How did its face contort under the Montana sun sense of what their subjects looked like, the findings some 66 million years ago? What color and texture also constrain their creativity, he says, by leaving fewer was its body? Was it gauntly wrapped in scales, fluffy details to the imagination. with feathers, or a mix of both? Even so, he and other artists welcome new discov- Increasingly, paleontologists can offer answers to eries, as the field strives for accuracy. The challenge these questions, thanks to evidence of dinosaur soft now is sifting through all this new information, including tissues discovered in the last 30 years. Translating those characteristics that are still up for debate, such as the discoveries into works that satisfy the public’simagination extent of T. rex’s feathers, to conjure new visions of the is the purview of paleoartists, the scientific illustrators prehistoric world. who reconstruct prehistory in paintings, drawings, and Paleoartists often have a general science back- sculptures in exhibit halls, books, magazines, and films. ground or formal artistic training, although career Among the earliest examples of paleoart, this 1830 watercolor painting, called Duria Antiquior or “A more ancient Dorset,” imagines England’s South Coast populated by ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and pterosaurs.