Solid Waste Management and Social Inclusion of Waste Pickers: Opportunities and Challenges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waste Picker Integration Guideline for South Africa

WASTE PICKER INTEGRATION GUIDELINE FOR SOUTH AFRICA Building the recycling economy and improving livelihoods through integration of the informal sector August 2020 Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries Department of Science and Innovation Document to be referenced as: Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries and Department of Science and Innovation (2020). Waste picker integration guideline for South Africa: Building the Recycling Economy and Improving Livelihoods through Integration of the Informal Sector. DEFF and DST: Pretoria. Cover photograph (2018) Jonathan Torgovnik, courtesy of WIEGO. Date: August 2020 © Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries Photo Credit: PETCO Foreword Covid-19 has affected many sectors of South Africa’s economy and negatively impacted the livelihoods of many people in the country. The waste sector has been hard hit during this tough period, with many in the waste management value chain, feeling the impact, including informal waste pickers. The post Covid-19 economic recovery demands that the waste sector rethink its approach to the protection of human health and the environment, and consider the urgent need to protect the livelihoods of those that are involved in the collection and selling of waste materials. The visible impacts of poor waste management have taken hold in the imagination of the public in recent years, with images of illegal dumping and marine litter appearing frequently in the media. However, there is a social element of waste management that is also grabbing the attention of the South African public, and rightly so for the role that they play in South Africa’s waste economy – the informal waste sector. -

Report on Health Related Issues of Informal Sector Involvement in Solid Waste Management Imprint

Report on health related issues of informal sector involvement in solid waste management Imprint The Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH was formed on 1 January 2011. It brings together the long-standing expertise of DED, GTZ and InWEnt. For further information, go to www.giz.de. This publication presents former GTZ activities; due to the change of the company‘s name, these will be referred to in the following as GIZ activities. Published by: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH Postfach 5180 65726 Eschborn / Germany T +49 61 96 79-0 F +49 61 96 79-11 15 E [email protected] I www.giz.de/recycling-partnerships Sector Project Recycling Partnerships (Förderung armutsorientierter und umweltverträglicher Kreislaufwirtschaft-Konzepte) Responsible: Sandra Spies, GIZ Author: Susy Lobo Ugalde/Asociación Centroamericana para la Economía, la Salud y el Ambiente (ACEPESA), with contributions from Sofía García Cortés (GIZ) Contact person at the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development: Franz Marré Eschborn, January 2011 Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... 3 Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................ 5 Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................... 6 Part 1. Introduction -

Waste Incineration and Informal Livelihoods: a Technical Guide on Waste-To-Energy Initiatives

WIEGO Technical Brief No 11 August 2019 Waste Incineration and Informal Livelihoods: A Technical Guide on Waste-to-Energy Initiatives Jeroen IJgosse WIEGO Technical Briefs The global research-policy-action network Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO) Technical Briefs provide guides for both specialized and nonspecialized audiences. These are designed to strengthen understanding and analysis of the situation of those working in the informal economy as well as of the policy environment and policy options. About the Author: Jeroen IJgosse is a senior international solid waste management advisor, an urban environmental specialist, trainer and process facilitator with 25 years of experience in solid waste management in Latin America, Africa, Asia and Eastern Europe. He has worked extensively in the fields of planning, process facilitation, institutional strengthening, policy development, financial issues, due diligence assessment and inclusive processes involving informal actors in solid waste management. After 20 years living and working in Latin America, he currently resides in the Netherlands. Publication date: August, 2019 ISBN number: 978-92-95106-36-9 Please cite this publication as: IJgosse, Jeroen. 2019. Waste Incineration and Informal Livelihoods: A Technical Guide on Waste-to-Energy Initiatives. WIEGO Technical Brief No. 11. Manchester, UK: WIEGO. Series editor: Caroline Skinner Copy editor: Megan MacLeod Layout: Julian Luckham of Luckham Creative Cover photo: Waste pickers working at the Kpone Landfill in Tema, Ghana face the threat of losing access to waste for recycling. Photo: Dean Saffron Published by Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO) A Charitable Company Limited by Guarantee – Company No. 6273538, Registered Charity No. -

Sustainable Waste Management in Rural Cities of Peru

Japanese Award for Most Innovative Development Project Section A: Program Information 1. Program Details Program Name: Sustainable Solid Waste Management in rural cities of Peru Year of 2004 implementation: Primary Contact Person/s: First name Albina Last name Ruiz Rios Designation Executive Director Telephone (51-1) 421 5163 Fax (51-1) 421 5167 Av. Jorge Basadre 255, oficina 401, Address San Isidro, Lima, Peru E-mail [email protected] Web site www.ciudadsaludable.org First name Javier Last name Flores External Affairs and Development Designation Telephone 973-380-2738 Director Fax 2 Suzan Court D3, West Orange, NJ Address 07052 USA E-mail [email protected] Web site www.ciudadsaludable.org 2. Summary of the Program (250 words) Worldwide, tens of millions of people suffer from improper disposal of solid wastes-- through contamination of air and water, and as a vector for transmission of disease, to cite just a few examples. Ciudad Saludable (CS) saw in the environmental, economic, health and social issues that were challenging rural cities of Peru not only an intractable problem, but also an opportunity: building a community-based industry of efficient solid waste management systems that facilitate cleaner cities and healthy individuals. The purpose of the program is: to work with public agencies to ensure trash removal services were coordinated and backed by public officials; to support initiatives to combat illegal dumping; to conduct public education campaigns to change habits of individuals and large institutions; to support the establishment and operation of community-organized collection, recycling and disposal micro- enterprises and operate an organic demonstration farm to train farmers in using compost and recycled organic waste. -

Unleashing Waste-Pickers Potential: Supporting Recycling Cooperatives in Santiago De Chile

Pablo Navarrete-Hernandez, Nicolas Navarrete- Hernandez Unleashing waste-pickers potential: supporting recycling cooperatives in Santiago de Chile Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Navarrete-Hernández, Pablo and Navarrete-Hernandez, Nicolas (2018) Unleashing waste- pickers potential: supporting recycling cooperatives in Santiago de Chile. World Development, 101. pp. 293-310. ISSN 0305-750X DOI: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.08.016 © 2017 Elsevier Ltd This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/85730/ Available in LSE Research Online: January 2018 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Unleashing Waste-Pickers’ Potential: Supporting Recycling Cooperatives in Santiago de Chile Pablo Navarrete-Hernandez, London School of Economics and Political Sciences Nicolas Navarrete-Hernandez, University of Warwick Abstract The informal economy currently provides two out of three jobs worldwide, with waste-picking activities providing employment for millions of the poorest of society. -

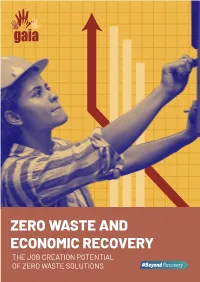

Zero Waste and Economic Recovery the Job Creation Potential

ZERO WASTE AND ECONOMIC RECOVERY THE JOB CREATION POTENTIAL OF ZERO WASTE SOLUTIONSThe Job Creation Potential of Zero Waste Solutions | 1 Figure 1: Waste Hierarchy with mean job generation figures per ten thousand tonnes of waste processed per year. The data show that waste management approaches that have the best environmental outcomes also generate the most jobs. RSIN, RC, RS* *The limited data available on the job creation potential of the strategies in the top tier of the hierarchy suggest that the magnitude of job growth potential Executive from this sector could be significant. Summary RPAIR 404 jobs Employment opportunities are important in any economy, and especially in times of economic downturn. As governments and the private sector invest in economic recovery strategies, particularly “green” or climate- neutral approaches, it is important to evaluate their employment potential. C40 estimates that the waste management sector has the potential to create 2.9 million jobs in its 97 member cities alone. RCYCL Zero waste—a comprehensive approach to waste management that RMANFACTR prioritizes waste prevention, re-use, composting, and recycling—is a widely-adopted strategy proven to minimize environmental impacts and 115 jobs 55 jobs contribute to a just society. In this study, we evaluate its job generation potential. The data for this study came from a wide range of sources spanning 16 countries. Despite the diversity in geographic and economic conditions, the results are clear: zero waste approaches create orders of magnitude more jobs than disposal-based systems that primarily burn or bury waste. Indeed, waste interventions can be ranked according to their job COMPOST generation potential, and this ranking exactly matches the traditional waste hierarchy based on environmental impacts (Figure 1). -

Waste Pickers/Recyclers Waste Pickers Collect, Sort, Recycle, Repurpose And/ Or Sell Materials Thrown Away by Others

Informal Economy IEMS Monitoring Study The Urban Informal Workforce: Waste Pickers/Recyclers Waste pickers collect, sort, recycle, repurpose and/ or sell materials thrown away by others. Their work reduces the amount of waste in municipal landfills, reclaims discarded material and reintroduces it into value chains. Waste pickers’ activities benefit the environment and public health. And in some cities, informal waste pickers are the only form of solid waste management — at little or no cost to the municipal budget. The Informal Economy Monitoring Belo Horizonte: D. Tomich Photo from Study (IEMS) examines the driving forces that shape waste pickers’ working conditions, their responses to these drivers, and the institutions that help or hinder their responses. Across five cities, 763 waste pickers (427 women and 336 men) took part in the research (see box below). Quantitative and qualitative data were collected in collaboration with their membership- based organizations in each city. The findings inform the recommendations on the last page of this report. Waste Pickers as Economic Agents Waste pickers provide recyclable materials to formal enterprises and generate demand for service providers. and one half also supply recyclable materials to informal businesses, private individuals and the • 76% of waste pickers in the sample say their main general public. buyers are formal businesses. Between one quarter • 34% of waste pickers use municipal services as part of their work, generating revenue for city About IEMS and the Research Partners governments. These findings are based on research conducted • 29% use public toilets, 18% pay for the services of in 2012 as part of the Informal Economy carriers and 17% use private transport in their work. -

Approaches to EPR and Implications for Waste Picker Integration

Approaches to EPR and implications for waste picker integration Prof Linda Godfrey Manager: Waste RDI Roadmap Implementation Unit, DST/CSIR Principal Scientist: CSIR Associate Professor: Northwest University DEA / Wits University Panel on EPR and IWMPs 21 November 2016 OUTLINE OF PRESENTATION • What is Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR)? • Context for EPR in South Africa • Big questions that need to be addressed • Approaches to integration of informal waste pickers 2 © CSIR 2016 www.csir.co.za EXTENDED PRODUCER RESPONSIBILITY • EPR is an advanced “policy approach in which a producer’s responsibility for a product is extended to the post-consumer stage of a product’s life cycle” (OECD, 2001) - It sets out obligations for producers to take back their products at the end of the products’ useful life - Shifts the responsibility (financial and/or operational) for the treatment or disposal of a product at end-of-life away from government to the producer - Relieves municipalities of some of the financial burden of waste management - Provides incentives to producers to incorporate environmental considerations in the design of their products 3 © CSIR 2016 www.csir.co.za EXTENDED PRODUCER RESPONSIBILITY • There is no single, internationally accepted “correct” model in terms of EPR scheme design and operation - Although the European Union is calling for the harmonisation of EPR schemes • There are various models of EPR design – - e.g. by country, by waste type, different roles and responsibilities 4 © CSIR 2016 www.csir.co.za EXTENDED PRODUCER RESPONSIBILITY Driving the supply side Driving the demand side e.g. subsidizing separation at source e.g. subsidizing recycling (negative value programmes, collection infrastructure waste streams) Typical EPR models e.g. -

The Full Issue of Perspectives (Pdf 351Kb)

The Schwab Foundation in Davos January 21-25 2004 SCHWAB FOUNDATION FOR SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP Supporting Social Entrepreneurs around the World PERSPECTIVES MY DAVOS INSIDE OUT 06.00 View from my window My badge Going to work Guards from far away Friendly guards? Elegant colleague Sunny view 07.00 Congress Center 09.00 Congress Center 11.00 Congress Center 13.00 Congress Center 15.00 Congress Center Outside clear skies! Nice stranger in the shuttle bus 17.00 Congress Center 19.00 Congress Center Last email of the day? Heading home My footprints 22.00 View from my window Welcome to the second issue of Perspectives, a periodical published by the Schwab Foundation for Social Entrepreneurship. In this issue, we have hoped to capture the “spirit of Davos” as described by Schwab Social Entrepreneurs and other participants coming into contact with them in this Alpine ski town between January 21st and 25th. Pamela Hartigan Managing Director Schwab Foundation 2 ARRIVED: SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP@DAVOS n the mid-nineties, social entrepreneurship began to visionaries seek to engage the mainstream, patience developing countries and at 15% in OECD countries. capture the imagination of development and social is on order. After three years, social entrepreneurship Creative approaches that build workable and Ipolicy practitioners. Social entrepreneurs offered a truly arrived at Davos in 2004. As one of the Schwab sustainable organizational structures to provide fresh start to solve seemingly intractable problems. Entrepreneurs pointed out, “we discerned a genuine public and private goods are urgently needed. Social shift in the general perception of social entrepreneurs are the catalysts that ensure that the Drawing on market-based mechanisms to create entrepreneurship, moving from the loony fringes benefits of international economic integration trickle positive change in the domains of education, the toward greater recognition and acceptability as a down. -

The Informal Recycling Sector in Developing Countries Organizing Waste Pickers to Enhance Their Impact Martin Medina

47221 NOTE NO. 44 – OCT 2008 GRIDLINES Sharing knowledge, experiences, and innovations in public-private partnerships in infrastructure Public Disclosure Authorized The informal recycling sector in developing countries Organizing waste pickers to enhance their impact Martin Medina or the urban poor in developing countries, the materials—after some sorting, cleaning, and informal waste recycling is a common processing—to scrap dealers, who in turn sell to Fway to earn income. There are few reliable industry. In these circumstances middlemen often estimates of the number of people engaged in earn large profits, while waste pickers are paid far waste picking or of its economic and environ- too little to escape poverty. mental impact. Yet studies suggest that when Public Disclosure Authorized organized and supported, waste picking can Municipalities often consider waste pickers a spur grassroots investment by poor people, problem. Indeed, unorganized waste picking can create jobs, reduce poverty, save municipali- have an adverse impact on neighborhoods and ties money, improve industrial competitive- cities. Waste pickers often scatter the contents of ness, conserve natural resources, and protect garbage bags or bins to salvage anything of value. the environment. Three models have been used They do not always put the garbage back, increas- to organize waste pickers: microenterprises, ing the municipality’s costs for waste collection. cooperatives, and public-private partnerships. Their carts may interfere with traffic. And if they These can lead to more efficient recycling and use horses or donkeys to pull their carts, the more effective poverty reduction. manure may end up on the streets. Municipal authorities often ban waste pickers’ activities. -

Inclusive Waste Management in Peru: Enabling the Business of Recycling

Opportunity Assessment Inclusive Waste Management in Peru: Enabling the Business of Recycling March 2018 By Ciudad Saludable and GloBal Fairness Initiative CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND OPPORTUNITY OVERVIEW ....................................................... 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................................................... 4 ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................................. 5 REPORT OBJECTIVE AND METHODOLOGY ................................................................................. 6 LEGAL FRAMEWORK ............................................................................................................................ 7 SECTION 1: WASTE MANAGEMENT MARKET IN PERU ........................................................ 12 RECYCLING VALUE CHAIN .......................................................................................................... 15 KEY ACTORS FOR ENGAGEMENT ............................................................................................. 17 OPPORTUNITY ANALYSIS ............................................................................................................ 20 SECTION 2: INCLUSIVE RECYCLING MODELS .......................................................................... 25 CIUDAD SALUDABLE .................................................................................................................... -

The Skoll World Forum on Social Entrepreneurship 2011 Large Scale Change 2 03

1 THE SKOLL WORLD FORUM ON SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP 2011 LARGE SCALE CHANGE 2 03 WELCOMEBY JEFF SKOLL IN THIS PROGRAMME THE SKOLL WORLD FORUM IS THE PREMIER, INTERNATIONAL PLATFORM FOR ACCELERATING ENTREPRENEURIAL APPROACHES AND INNOVATIVE SOLUTIONS TO THE WORLD’S MOST BACKGROUND 4 PRESSING SOCIAL ISSUES. THEME 2011 5 It’s with gratitude and hope that I welcome all of you to Oxford – I believe that this level of collaborative action must become the PROGRAMME OVERVIEW 6 not only all of you game-changing social entrepreneurs, but also new normal, where policy makers, CEOs, funders, and social SOCIAL MEDIA 7 the many distinguished allies here from government, industry, entrepreneurs work side by side to tackle these seemingly academia, philanthropy, and the public interest sectors. insurmountable problems. Perhaps that’s the game-changing HIGHLIGHTS 8 innovation we need most: the will to make it so. Issues today are more complex, urgent and interconnected WEDNESDAY 10 than ever before, requiring insights, innovations and mindsets Jeff Skoll, Founder & Chairman, THURSDAY 12 to match. Large scale change demands that our solutions cross Skoll Foundation, Participant nations, sectors, and institutional boundaries. Whether it is FRIDAY 20 Media, and Skoll Global climate change, education, water scarcity or human rights, the Threats Fund SPEAKER BIOGRAPHIES 26 only way we are going to survive as a species is to pull together in our collective self-interest. Our way of looking at the world DELEGATE DETAILS 62 must shift from disparate players and solutions to an ecosystem THANK YOU 77 approach that engages all actors. A key imperative of the Skoll NEED TO KNOW 78 World Forum is to cultivate the collaborations and grow the networks that will propel these social entrepreneurs and their innovations to global impact.