Waste Picker Integration Guideline for South Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waste Incineration and Informal Livelihoods: a Technical Guide on Waste-To-Energy Initiatives

WIEGO Technical Brief No 11 August 2019 Waste Incineration and Informal Livelihoods: A Technical Guide on Waste-to-Energy Initiatives Jeroen IJgosse WIEGO Technical Briefs The global research-policy-action network Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO) Technical Briefs provide guides for both specialized and nonspecialized audiences. These are designed to strengthen understanding and analysis of the situation of those working in the informal economy as well as of the policy environment and policy options. About the Author: Jeroen IJgosse is a senior international solid waste management advisor, an urban environmental specialist, trainer and process facilitator with 25 years of experience in solid waste management in Latin America, Africa, Asia and Eastern Europe. He has worked extensively in the fields of planning, process facilitation, institutional strengthening, policy development, financial issues, due diligence assessment and inclusive processes involving informal actors in solid waste management. After 20 years living and working in Latin America, he currently resides in the Netherlands. Publication date: August, 2019 ISBN number: 978-92-95106-36-9 Please cite this publication as: IJgosse, Jeroen. 2019. Waste Incineration and Informal Livelihoods: A Technical Guide on Waste-to-Energy Initiatives. WIEGO Technical Brief No. 11. Manchester, UK: WIEGO. Series editor: Caroline Skinner Copy editor: Megan MacLeod Layout: Julian Luckham of Luckham Creative Cover photo: Waste pickers working at the Kpone Landfill in Tema, Ghana face the threat of losing access to waste for recycling. Photo: Dean Saffron Published by Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO) A Charitable Company Limited by Guarantee – Company No. 6273538, Registered Charity No. -

Unleashing Waste-Pickers Potential: Supporting Recycling Cooperatives in Santiago De Chile

Pablo Navarrete-Hernandez, Nicolas Navarrete- Hernandez Unleashing waste-pickers potential: supporting recycling cooperatives in Santiago de Chile Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Navarrete-Hernández, Pablo and Navarrete-Hernandez, Nicolas (2018) Unleashing waste- pickers potential: supporting recycling cooperatives in Santiago de Chile. World Development, 101. pp. 293-310. ISSN 0305-750X DOI: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.08.016 © 2017 Elsevier Ltd This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/85730/ Available in LSE Research Online: January 2018 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Unleashing Waste-Pickers’ Potential: Supporting Recycling Cooperatives in Santiago de Chile Pablo Navarrete-Hernandez, London School of Economics and Political Sciences Nicolas Navarrete-Hernandez, University of Warwick Abstract The informal economy currently provides two out of three jobs worldwide, with waste-picking activities providing employment for millions of the poorest of society. -

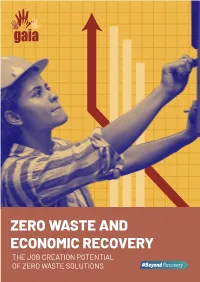

Zero Waste and Economic Recovery the Job Creation Potential

ZERO WASTE AND ECONOMIC RECOVERY THE JOB CREATION POTENTIAL OF ZERO WASTE SOLUTIONSThe Job Creation Potential of Zero Waste Solutions | 1 Figure 1: Waste Hierarchy with mean job generation figures per ten thousand tonnes of waste processed per year. The data show that waste management approaches that have the best environmental outcomes also generate the most jobs. RSIN, RC, RS* *The limited data available on the job creation potential of the strategies in the top tier of the hierarchy suggest that the magnitude of job growth potential Executive from this sector could be significant. Summary RPAIR 404 jobs Employment opportunities are important in any economy, and especially in times of economic downturn. As governments and the private sector invest in economic recovery strategies, particularly “green” or climate- neutral approaches, it is important to evaluate their employment potential. C40 estimates that the waste management sector has the potential to create 2.9 million jobs in its 97 member cities alone. RCYCL Zero waste—a comprehensive approach to waste management that RMANFACTR prioritizes waste prevention, re-use, composting, and recycling—is a widely-adopted strategy proven to minimize environmental impacts and 115 jobs 55 jobs contribute to a just society. In this study, we evaluate its job generation potential. The data for this study came from a wide range of sources spanning 16 countries. Despite the diversity in geographic and economic conditions, the results are clear: zero waste approaches create orders of magnitude more jobs than disposal-based systems that primarily burn or bury waste. Indeed, waste interventions can be ranked according to their job COMPOST generation potential, and this ranking exactly matches the traditional waste hierarchy based on environmental impacts (Figure 1). -

Waste Pickers/Recyclers Waste Pickers Collect, Sort, Recycle, Repurpose And/ Or Sell Materials Thrown Away by Others

Informal Economy IEMS Monitoring Study The Urban Informal Workforce: Waste Pickers/Recyclers Waste pickers collect, sort, recycle, repurpose and/ or sell materials thrown away by others. Their work reduces the amount of waste in municipal landfills, reclaims discarded material and reintroduces it into value chains. Waste pickers’ activities benefit the environment and public health. And in some cities, informal waste pickers are the only form of solid waste management — at little or no cost to the municipal budget. The Informal Economy Monitoring Belo Horizonte: D. Tomich Photo from Study (IEMS) examines the driving forces that shape waste pickers’ working conditions, their responses to these drivers, and the institutions that help or hinder their responses. Across five cities, 763 waste pickers (427 women and 336 men) took part in the research (see box below). Quantitative and qualitative data were collected in collaboration with their membership- based organizations in each city. The findings inform the recommendations on the last page of this report. Waste Pickers as Economic Agents Waste pickers provide recyclable materials to formal enterprises and generate demand for service providers. and one half also supply recyclable materials to informal businesses, private individuals and the • 76% of waste pickers in the sample say their main general public. buyers are formal businesses. Between one quarter • 34% of waste pickers use municipal services as part of their work, generating revenue for city About IEMS and the Research Partners governments. These findings are based on research conducted • 29% use public toilets, 18% pay for the services of in 2012 as part of the Informal Economy carriers and 17% use private transport in their work. -

Approaches to EPR and Implications for Waste Picker Integration

Approaches to EPR and implications for waste picker integration Prof Linda Godfrey Manager: Waste RDI Roadmap Implementation Unit, DST/CSIR Principal Scientist: CSIR Associate Professor: Northwest University DEA / Wits University Panel on EPR and IWMPs 21 November 2016 OUTLINE OF PRESENTATION • What is Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR)? • Context for EPR in South Africa • Big questions that need to be addressed • Approaches to integration of informal waste pickers 2 © CSIR 2016 www.csir.co.za EXTENDED PRODUCER RESPONSIBILITY • EPR is an advanced “policy approach in which a producer’s responsibility for a product is extended to the post-consumer stage of a product’s life cycle” (OECD, 2001) - It sets out obligations for producers to take back their products at the end of the products’ useful life - Shifts the responsibility (financial and/or operational) for the treatment or disposal of a product at end-of-life away from government to the producer - Relieves municipalities of some of the financial burden of waste management - Provides incentives to producers to incorporate environmental considerations in the design of their products 3 © CSIR 2016 www.csir.co.za EXTENDED PRODUCER RESPONSIBILITY • There is no single, internationally accepted “correct” model in terms of EPR scheme design and operation - Although the European Union is calling for the harmonisation of EPR schemes • There are various models of EPR design – - e.g. by country, by waste type, different roles and responsibilities 4 © CSIR 2016 www.csir.co.za EXTENDED PRODUCER RESPONSIBILITY Driving the supply side Driving the demand side e.g. subsidizing separation at source e.g. subsidizing recycling (negative value programmes, collection infrastructure waste streams) Typical EPR models e.g. -

The Informal Recycling Sector in Developing Countries Organizing Waste Pickers to Enhance Their Impact Martin Medina

47221 NOTE NO. 44 – OCT 2008 GRIDLINES Sharing knowledge, experiences, and innovations in public-private partnerships in infrastructure Public Disclosure Authorized The informal recycling sector in developing countries Organizing waste pickers to enhance their impact Martin Medina or the urban poor in developing countries, the materials—after some sorting, cleaning, and informal waste recycling is a common processing—to scrap dealers, who in turn sell to Fway to earn income. There are few reliable industry. In these circumstances middlemen often estimates of the number of people engaged in earn large profits, while waste pickers are paid far waste picking or of its economic and environ- too little to escape poverty. mental impact. Yet studies suggest that when Public Disclosure Authorized organized and supported, waste picking can Municipalities often consider waste pickers a spur grassroots investment by poor people, problem. Indeed, unorganized waste picking can create jobs, reduce poverty, save municipali- have an adverse impact on neighborhoods and ties money, improve industrial competitive- cities. Waste pickers often scatter the contents of ness, conserve natural resources, and protect garbage bags or bins to salvage anything of value. the environment. Three models have been used They do not always put the garbage back, increas- to organize waste pickers: microenterprises, ing the municipality’s costs for waste collection. cooperatives, and public-private partnerships. Their carts may interfere with traffic. And if they These can lead to more efficient recycling and use horses or donkeys to pull their carts, the more effective poverty reduction. manure may end up on the streets. Municipal authorities often ban waste pickers’ activities. -

The Formalization of Waste Picker Organizations in Bogotá

Running head: THE FORMALIZATION OF WASTE PICKER ORGANIZATIONS IN BOGOTÁ Neoliberalism versus Social Rights: The Formalization of Waste Picker Organizations in Bogotá, Colombia Emilie Sing A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of M.A. International Development and Globalization School of International Development and Global Studies Faculty of Social Sciences University of Ottawa © Emilie Sing, Ottawa, Canada, 2018 THE FORMALIZATION OF WASTE PICKER ORGANIZATIONS IN BOGOTÁ Table of Content Table of Content ........................................................................................................................................... ii List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................... iv List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................... v List of Photos ............................................................................................................................................... vi Abbreviations .............................................................................................................................................. vii Glossary ....................................................................................................................................................... ix Abstract -

The Global Impact of E-Waste: Addressing the Challenge the Global Impact of E-Waste: Addressing the Challenge

The global impact of e-waste Addressing the challenge challenge the Addressing e-waste of impact global The International Labour Office International Labour Office SECTOR SafeWork 4, route des Morillons 4, route des Morillons CH-1211 Genève 22 CH-1211 Genève 22 SECTOR SafeWork Switzerland Switzerland Sectoral Programme on Tel. +41-22-799 7501 Tel. +41-22-799 6715 Activities Safety and Health Department at Work and the Fax +41-22-799 7050 Fax +41-22-799 6878 Environment E-mail [email protected] E-mail [email protected] ILO The global impact of e-waste: Addressing the challenge The global impact of e-waste: Addressing the challenge Karin Lundgren SafeWork and SECTOR International Labour Organization Geneva 2012 Copyright © International Labour Organization 2012 First published 2012 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Permissions), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with reproduction rights organizations may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. Lundgren, Karin The global impact of e-waste: addressing the challenge / Karin Lundgren; International Labour Office, Programme on Safety and Health at Work and the Environment (SafeWork), Sectoral Activities Department (SECTOR). -

Waste Pickers in Time of Crisis

A P R I L 2 0 2 0 WASTE PICKERS IN TIME OF CRISIS NO-BURN.ORG In the context of waste, this worldwide pause in which Covid-19 has put us, brings a series of environmental, social and cultural challenges. These challenges will affect short- and long-term plans of many organizations, groups, the academy, movements and international alliances. This information aims to provide a diagnosis of the current global situation of waste pickers - informal waste workers that provide a waste management service and contribute to public health and sustainability but lack social and health protection. The following information was sourced from our members on the ground, and we hope will help inform and prioritise lines of action aimed at solving the urgent needs of the waste management system’s most vulnerable actors. Waste Pickers People in the informal waste sector--those who do the critical yet thankless role of collecting and sorting our waste and recyclables without formal recognition and protections from their municipalities-- are now facing a grave threat. 15 million informal waste workers and their families risk losing their livelihood due to Covid-19. The violation of the fundamental rights of waste pickers has been a matter of constant concern, leading workers to organize at local, regional and global levels. The following list summarizes their demands in response to the critical situation they face today. N O - B U R N . O R G Waste Pickers and Human Rights Violation of the fundamental rights of workers is a matter of global discussion. Among them are: Unsafe and unhealthy work conditions. -

The Transformative Politics of Labor and Extended Producer Responsibility Under Brazil’S National Solid Waste Policy

Co-Opting Sustainabilities: The Transformative Politics of Labor and Extended Producer Responsibility Under Brazil’s National Solid Waste Policy By Talia Mestel Fox B.A. in Linguistics Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts (2013) Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2018 © 2018 Talia Mestel Fox. All Rights Reserved The author hereby grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Author________________________________________________________________________ Department of Urban Studies and Planning May 24, 2018 Certified by____________________________________________________________________ Assistant Professor Gabriella Y. Carolini Department of Urban Studies and Planning Thesis Supervisor Accepted by___________________________________________________________________ Professor of the Practice, Ceasar McDowell Chair, MCP Committee Department of Urban Studies and Planning Co-Opting Sustainabilities: The Transformative Politics of Labor and Extended Producer Responsibility Under Brazil’s National Solid Waste Policy By Talia Mestel Fox Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 24, 2018, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning Abstract Growing levels of global solid waste production implore society to identify the actors responsible for preventing, reducing, and disposing of wasted material in a sustainable manner. Extended producer responsibility (EPR) and corporate social responsibility (CSR) are policy frameworks that hold accountable the manufacturers of goods that create post-consumer waste. National and state governments typically prescribe EPR through market mechanisms, performance standards, and disclosure requirements. -

The Waste Picker Revolution in This Issue

The Waste Picker Revolution In this issue groundWork is a non-profit environmental justice organization working primarily in 3 From the Smoke Stack South Africa, but increasingly in Southern Africa. groundWork seeks to improve the 5 Health, pollution and the climate crisis quality of life of vulnerable people in Southern Africa through assisting civil society to have a greater impact on 7 Green procurement workshop environmental governanace. groundWork places particular emphasis on assisting vulnerable and previously disadvantaged 9 Brand Audit 2019 people who are most affected by environmental injustices. groundWork’s current campaign areas 10 Bully-boy “SLAPP suits” on the rise are: Climate Justice and Energy, Coal, Waste and Environmental Health. groundWork is constituted as a trust. 11 A decade of successful struggle The Chairperson of the Board of Trustees is Joy Kistnasamy, lecturer in environmental health at the Durban 13 Kigali – clean vision University of Technology. The other trustees are: Farid Esack, Patrick Kulati, Richard Lyster, Sandile Ndawonde and 14 Clean Coal Jon White. 15 Air Quality and Health Literacy groundWork’s STAFF ARE: Director: Bobby Peek Deputy Director: Gill Addison Administrative Assistant: Bathoko Sibisi Waste Campaign Manager: Musa Chamane Coal Campaign Manager: Robby Mokgalaka Environmental Health Campaign Help us spread the word Manager: Rico Euripidou www.twitter.com/ Campaign Research and Technical www.facebook.com/ groundworksa Assistant: Niven Reddy groundWorkSA Global Green and Healthy Hospital -

Waste Pickers' Cooperatives and Social and Solidarity Economy

COOPERATIVES AND THE WORLD OF WORK NO 12 Waste pickers’ cooperatives and social and solidarity economy organizations INTRODUCTION Effective waste management is essential to safeguarding public health waste collection in many cities in developing countries at no cost to and sanitation, protecting environment, and improving resource municipalities.7 A study in 2007 found that waste pickers recovered efficiency. Solid waste management is almost always the responsibility of approximately 20 per cent of all waste material in three of six cities local governments and is often their single largest budget item particularly studied.8 Despite these environmental and social contributions, waste in developing countries.1 However, it remains a challenge due to limited pickers are often not legally recognized as workers. They suffer from poor financial, physical and human resources. In countries and cities where working conditions and lack social protection. The following are among formal waste management systems are underdeveloped, informal waste the major decent work deficits waste pickers face around the world.9, 10 pickers have long played a key role in collecting, sorting and recycling • Hazardous working environment and lack of occupational safety and waste. health (OSH): Waste pickers regularly face risks of diseases and injuries Waste pickers range from people rummaging through garbage in search by being exposed to toxic materials, contaminated residues, or sharp- of food, clothing and other basic, daily needs to informal private collectors edged items. Those operating in open dumps or landfills confront of recyclables for sale to middlemen or businesses, as well as organized particular risks of injuries or even loss of life, as they can be run over collectors and sorters of recyclables.2 The majority of waste pickers deal by trucks or become victims of surface subsidence, slides and fires.