The Transformative Politics of Labor and Extended Producer Responsibility Under Brazil’S National Solid Waste Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waste Picker Integration Guideline for South Africa

WASTE PICKER INTEGRATION GUIDELINE FOR SOUTH AFRICA Building the recycling economy and improving livelihoods through integration of the informal sector August 2020 Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries Department of Science and Innovation Document to be referenced as: Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries and Department of Science and Innovation (2020). Waste picker integration guideline for South Africa: Building the Recycling Economy and Improving Livelihoods through Integration of the Informal Sector. DEFF and DST: Pretoria. Cover photograph (2018) Jonathan Torgovnik, courtesy of WIEGO. Date: August 2020 © Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries Photo Credit: PETCO Foreword Covid-19 has affected many sectors of South Africa’s economy and negatively impacted the livelihoods of many people in the country. The waste sector has been hard hit during this tough period, with many in the waste management value chain, feeling the impact, including informal waste pickers. The post Covid-19 economic recovery demands that the waste sector rethink its approach to the protection of human health and the environment, and consider the urgent need to protect the livelihoods of those that are involved in the collection and selling of waste materials. The visible impacts of poor waste management have taken hold in the imagination of the public in recent years, with images of illegal dumping and marine litter appearing frequently in the media. However, there is a social element of waste management that is also grabbing the attention of the South African public, and rightly so for the role that they play in South Africa’s waste economy – the informal waste sector. -

5 Steps to Responsible E-Waste Management at Your School

By Caprice Lawless Steps to Responsible E-waste 5 Management at Your School aste management infra Step 1. Educate yourself about local, national, and international legislation. structure is expanding While recycling standards and certifications are still in the developmental stag Was we wrestle with how es, many cities and states are leading the way with ambitious and comprehen best to gather, sort, and recycle the sive programs addressing the situation. California’s landmark Electronic Waste 50 million tons of e-waste we are Recycling Act of 2003, for example, requires retailers to collect a fee from con generating annually worldwide. sumers on covered electronic devices. The fees are then submitted to the state Awareness and education are the to pay for recycling efforts. first steps, followed by programs In February 2008, New York City became the first U.S. city to pass a manda and industries to address the issue. tory producer-responsibility ordinance. The law requires computer, TV, and Schools, districts, and colleges of MP3 manufacturers to take responsibility for the collection of their own elec education contribute their share of tronic products for New Yorkers who discard 25,000 tons of e-waste each year. e-waste and need to be concerned In January 2008, New Jersey joined California, Connecticut, Maine, Minnesota, with its disposal, but they can also North Carolina, Oregon, Texas, and Washington, in passing “take-back” laws put into place their own refurbish requiring manufacturers to collect and recycle e-waste. It is already illegal to ing programs and partnerships and dump e-waste in 10 states, with similar legislation pending in many others. -

Estimating the Deep Decarbonization Benefits of the Electric Mobility Transition: a Review of Managed Charging Strategies and Second-Life Battery Uses

Estimating the Deep Decarbonization Benefits of the Electric Mobility Transition: A Review of Managed Charging Strategies and Second-Life Battery Uses Matthew D. Dean1 and Kara M. Kockelman, Ph.D., P.E.2 1Department of Civil, Architectural and Environmental Engineering, University of Texas at Austin, 1 University Station (Mail Code C1761), Austin, TX 78712; email: [email protected] 2Department of Civil, Architectural and Environmental Engineering, University of Texas at Austin, 1 University Station (Mail Code C1761), Austin, TX 78712; email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Emissions-reduction pathways in transportation are often characterized as a “three-legged stool”, where vehicle efficiency, fuel carbon content, and vehicle miles traveled (VMT) contribute to lower emissions. The electric mobility (e-mobility) transition provides fast savings since plug-in electric vehicles (PEVs) are nearly three times more energy efficient than internal combustion engines (ICEs) and most nations’ power grids are lowering their carbon intensity irrespective of any further climate policy. The transportation sector’s greenhouse gas (GHG) savings via electrification are subject to many variables – such as power plant feedstocks, vehicle charging locations and schedules, vehicle size and weight, driver behavior, and annual mileage, which are described in existing literature. Savings will also depend on emerging innovations, such as managed charging (MC) strategies and second-life battery use in energy storage systems (B2U- ESS). This paper’s review of MC strategies and B2U-ESS applications estimates additional GHG savings to be up to 33% if chargers are widely available for MC-enabled passenger cars, and up to 100% if B2U-ESS abates peaker plants over its second-use lifetime. -

Waste Incineration and Informal Livelihoods: a Technical Guide on Waste-To-Energy Initiatives

WIEGO Technical Brief No 11 August 2019 Waste Incineration and Informal Livelihoods: A Technical Guide on Waste-to-Energy Initiatives Jeroen IJgosse WIEGO Technical Briefs The global research-policy-action network Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO) Technical Briefs provide guides for both specialized and nonspecialized audiences. These are designed to strengthen understanding and analysis of the situation of those working in the informal economy as well as of the policy environment and policy options. About the Author: Jeroen IJgosse is a senior international solid waste management advisor, an urban environmental specialist, trainer and process facilitator with 25 years of experience in solid waste management in Latin America, Africa, Asia and Eastern Europe. He has worked extensively in the fields of planning, process facilitation, institutional strengthening, policy development, financial issues, due diligence assessment and inclusive processes involving informal actors in solid waste management. After 20 years living and working in Latin America, he currently resides in the Netherlands. Publication date: August, 2019 ISBN number: 978-92-95106-36-9 Please cite this publication as: IJgosse, Jeroen. 2019. Waste Incineration and Informal Livelihoods: A Technical Guide on Waste-to-Energy Initiatives. WIEGO Technical Brief No. 11. Manchester, UK: WIEGO. Series editor: Caroline Skinner Copy editor: Megan MacLeod Layout: Julian Luckham of Luckham Creative Cover photo: Waste pickers working at the Kpone Landfill in Tema, Ghana face the threat of losing access to waste for recycling. Photo: Dean Saffron Published by Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO) A Charitable Company Limited by Guarantee – Company No. 6273538, Registered Charity No. -

The EPR Trilogy

The EPR Trilogy ©2012 Nancy Gorrell Together At Last: Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) and Total Recycling Total Recovery for Reuse, Recycling, and Composting: How to Make It So Extended Producer Responsibility in British Columbia – A Work at Risk These articles were written individually for publication elsewhere and are collected here pre-publication for distribution to attendees at the Northern California Recycling Association’s Recycling Update XVII, March 27, 2012. They are presented in the order written. The EPR Trilogy, Urban Ore, for NCRA’s Recycling Update March 27, 2012 1 ©2012 Nancy Gorrell©2012 The authors and artist retain their copyrights. Booklet ©2012 Urban Ore, Inc. 900 Murray St., Berkeley, CA 94710 http://urbanore.com No part of this publication may be reproduced without written permission from the appropriate copyright owner. 2 The EPR Trilogy, Urban Ore, for NCRA’s Recycling Update March 27, 2012 Together At Last: Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) and Total Recycling Daniel Knapp, Ph.D. years ago developed a rhetoric that The CPSC Webinar focused on just assumed recycling was in the way one commodity type: batteries. The and had to be set aside for EPR to speakers were actually part of the EPR versus Total Recycling. work. This rhetoric often resorted to battery reclamation supply chain in Sometime in the cold wet spring sloganeering: recycling was “so last various parts of California. My big of 2011, NCRA President Arthur century,” recycling “enables wasting.” takeaway from a day of listening: Boone set up what he hoped would They said EPR, pursued correctly, as EPR ideas are being tested and be a stirring and member-pleasing made recycling outmoded and refined in actual practice, reality is debate between opponents on the unnecessary, because products would forcing EPR and total recycling back EPR issue. -

Governments Struggle with Zero Waste Planning, Policy

GOVERNMENTS STRUGGLE WITH ZERO WASTE PLANNING, POLICY, AND IMPLEMENTATION The challenges faced by local to national governments that are planning for and implementing zero waste initiatives and the synchronicity necessary to achieve it. by BRIANNA BEYNART A thesis submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Baltimore, Maryland December 2019 © 2019 Brianna Beynart All Rights Reserved Abstract With growing concern over the shortage of landfill space and the health hazards of waste incineration, governments are looking towards sustainable waste management processes for the health of their communities. Zero waste is the goal to direct 100 percent of waste from landfills and incinerators, which is ultimately the most sustainable waste management strategy. Many governments have been working towards zero waste but none have achieved 100 percent waste diversion. Using a comparative context, it is the goal of this research to determine what planning practices are shared across varying levels of governments and from diverse geographic locations to determine what obstacles are preventing them from achieving 100 percent waste diversion. This research builds on the discoveries of each preceding finding and topics of this research include zero waste planning, waste management and processing methods, best practices for zero waste management, public outreach, public resource requirements for a zero waste community, and the role of the producer in the waste management cycle. The first section compares the zero waste plans of three American cities to reveal common best practices. Success was shared through outreach and the availability of public resources. The cities ultimately struggled to separate and process the waste after it had been collected. -

Unleashing Waste-Pickers Potential: Supporting Recycling Cooperatives in Santiago De Chile

Pablo Navarrete-Hernandez, Nicolas Navarrete- Hernandez Unleashing waste-pickers potential: supporting recycling cooperatives in Santiago de Chile Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Navarrete-Hernández, Pablo and Navarrete-Hernandez, Nicolas (2018) Unleashing waste- pickers potential: supporting recycling cooperatives in Santiago de Chile. World Development, 101. pp. 293-310. ISSN 0305-750X DOI: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.08.016 © 2017 Elsevier Ltd This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/85730/ Available in LSE Research Online: January 2018 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Unleashing Waste-Pickers’ Potential: Supporting Recycling Cooperatives in Santiago de Chile Pablo Navarrete-Hernandez, London School of Economics and Political Sciences Nicolas Navarrete-Hernandez, University of Warwick Abstract The informal economy currently provides two out of three jobs worldwide, with waste-picking activities providing employment for millions of the poorest of society. -

A 30-Day Roadmap to Zero Waste

#MAKEITAHABIT A 30-DAY ROADMAP TO ZERO WASTE www.greatforest.com What is Zero Waste? In short, Zero Waste is a holistic way of thinking that views materials as resources within a circular, closed-loop system. As officially defined by the Zero Waste International Alliance (ZWIA), Zero Waste is “The conservation of all resources by means of responsible production, consumption, reuse, and recovery of products, packaging, and materials without burning and with no discharges to land, water, or air that threaten the environment or human health.” Instructions This 30-day roadmap was developed to provide simple, actionable ways for you to get started on your Zero Waste journey from home. While Great Forest works to help businesses nationwide reduce waste and increase sustainability, we firmly believe that good zero waste habits and climate action starts at home. Each action within the roadmap can be completed independently of the other actions, we recommend following the order laid out to help reinforce Zero Waste-inspired themes that build on each other. Each action comes with a short description, simple tip(s), and resources for you to get started right away. The Great Forest consultant team had a fun time creating this toolkit and hope you will enjoy following along with us. The key is to get creative and involve your family, friends, and neighbors whenever possible! #MAKEITAHABIT Take stock of your Zero Waste journey. Assess your at-home waste footprint. Determining the amount of waste you produce through your daily routine is the first step to fixing it. This is one of those things you can't "un-know" once you know. -

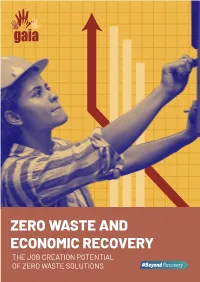

Zero Waste and Economic Recovery the Job Creation Potential

ZERO WASTE AND ECONOMIC RECOVERY THE JOB CREATION POTENTIAL OF ZERO WASTE SOLUTIONSThe Job Creation Potential of Zero Waste Solutions | 1 Figure 1: Waste Hierarchy with mean job generation figures per ten thousand tonnes of waste processed per year. The data show that waste management approaches that have the best environmental outcomes also generate the most jobs. RSIN, RC, RS* *The limited data available on the job creation potential of the strategies in the top tier of the hierarchy suggest that the magnitude of job growth potential Executive from this sector could be significant. Summary RPAIR 404 jobs Employment opportunities are important in any economy, and especially in times of economic downturn. As governments and the private sector invest in economic recovery strategies, particularly “green” or climate- neutral approaches, it is important to evaluate their employment potential. C40 estimates that the waste management sector has the potential to create 2.9 million jobs in its 97 member cities alone. RCYCL Zero waste—a comprehensive approach to waste management that RMANFACTR prioritizes waste prevention, re-use, composting, and recycling—is a widely-adopted strategy proven to minimize environmental impacts and 115 jobs 55 jobs contribute to a just society. In this study, we evaluate its job generation potential. The data for this study came from a wide range of sources spanning 16 countries. Despite the diversity in geographic and economic conditions, the results are clear: zero waste approaches create orders of magnitude more jobs than disposal-based systems that primarily burn or bury waste. Indeed, waste interventions can be ranked according to their job COMPOST generation potential, and this ranking exactly matches the traditional waste hierarchy based on environmental impacts (Figure 1). -

Waste Pickers/Recyclers Waste Pickers Collect, Sort, Recycle, Repurpose And/ Or Sell Materials Thrown Away by Others

Informal Economy IEMS Monitoring Study The Urban Informal Workforce: Waste Pickers/Recyclers Waste pickers collect, sort, recycle, repurpose and/ or sell materials thrown away by others. Their work reduces the amount of waste in municipal landfills, reclaims discarded material and reintroduces it into value chains. Waste pickers’ activities benefit the environment and public health. And in some cities, informal waste pickers are the only form of solid waste management — at little or no cost to the municipal budget. The Informal Economy Monitoring Belo Horizonte: D. Tomich Photo from Study (IEMS) examines the driving forces that shape waste pickers’ working conditions, their responses to these drivers, and the institutions that help or hinder their responses. Across five cities, 763 waste pickers (427 women and 336 men) took part in the research (see box below). Quantitative and qualitative data were collected in collaboration with their membership- based organizations in each city. The findings inform the recommendations on the last page of this report. Waste Pickers as Economic Agents Waste pickers provide recyclable materials to formal enterprises and generate demand for service providers. and one half also supply recyclable materials to informal businesses, private individuals and the • 76% of waste pickers in the sample say their main general public. buyers are formal businesses. Between one quarter • 34% of waste pickers use municipal services as part of their work, generating revenue for city About IEMS and the Research Partners governments. These findings are based on research conducted • 29% use public toilets, 18% pay for the services of in 2012 as part of the Informal Economy carriers and 17% use private transport in their work. -

The Environmental Impact of Technological Innovation: How U.S. Legislation Fails to Handle Electronic Waste's Rapid Growth

Volume 32 Issue 1 Article 6 2-12-2021 The Environmental Impact of Technological Innovation: How U.S. Legislation Fails to Handle Electronic Waste's Rapid Growth Marisa D. Pescatore Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/elj Part of the Commercial Law Commons, Communications Law Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Environmental Law Commons, International Humanitarian Law Commons, International Law Commons, International Trade Law Commons, Legislation Commons, National Security Law Commons, Science and Technology Law Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Marisa D. Pescatore, The Environmental Impact of Technological Innovation: How U.S. Legislation Fails to Handle Electronic Waste's Rapid Growth, 32 Vill. Envtl. L.J. 115 (2021). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/elj/vol32/iss1/6 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Villanova Environmental Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Pescatore: The Environmental Impact of Technological Innovation: How U.S. Le THE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT OF TECHNOLOGICAL INNOVATION: HOW U.S. LEGISLATION FAILS TO HANDLE ELECTRONIC WASTE’S RAPID GROWTH “The U.S. has always been the elephant in the room that no- body wants to talk about . Until it decides to play a part, we can’t really solve the problem of e-waste -

Tools for Promoting Industrial Symbiosis: a Systematic Review

Manuscript version: Author’s Accepted Manuscript The version presented in WRAP is the author’s accepted manuscript and may differ from the published version or Version of Record. Persistent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/139307 How to cite: Please refer to published version for the most recent bibliographic citation information. If a published version is known of, the repository item page linked to above, will contain details on accessing it. Copyright and reuse: The Warwick Research Archive Portal (WRAP) makes this work by researchers of the University of Warwick available open access under the following conditions. Copyright © and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in WRAP has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. Publisher’s statement: Please refer to the repository item page, publisher’s statement section, for further information. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected]. warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Tools for promoting industrial symbiosis: A systematic review Zhiquan Yeoa,b, Donato Masic, Jonathan