Kent Business School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Competition Report Q2 2017

NATIONAL COMPETITION QUARTERLY REPORT APRIL– JUNE 2017 BELGIUM basis of their “Best and Final Offer.” Third, Infrabel issued individual calls for specific orders within the This section reviews developments under Book IV of the terms and conditions of the framework agreement. The Belgian Code of Economic Law (“CEL”) on the selected companies had to submit their best offer for Protection of Competition, which is enforced by the each call, and the orders were awarded to the lowest Belgian Competition Authority (“the BCA”). Within the bidder. BCA, the Prosecutor General and its staff of prosecutors (collectively, the “Auditorate”) investigate In 2013, the Auditorate started investigating this public alleged restrictive practices and concentrations, while procurement following ABB’s leniency application. the Competition College (the “College”) functions as The investigation revealed that the bidders had agreed the decision-making body. Prior to September 6, 2013, to allocate the orders placed by Infrabel amongst Belgian competition law was codified in the Act on the themselves. For each call, they exchanged price Protection of Economic Competition of September 15, information and instructions to ensure that the 2006 (“APEC”) and enforced by the Belgian pre-designated participant would present the lowest Competition Authority, then composed of the price and win the tender. The Auditorate found that Directorate General for Competition and the these practices had started in 2010–2011 and continued Competition Council. When relevant, entries in this until June 2016. The Auditorate notified its objections report will refer to the former sub-bodies of the BCA. to the companies in August 2016, and settlement talks began a month later. -

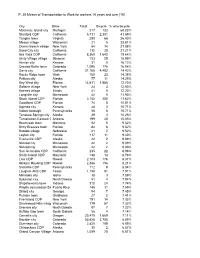

Copy of Censusdata

P. 30 Means of Transportation to Work for workers 16 years and over [16] City State Total: Bicycle % who bicycle Mackinac Island city Michigan 217 132 60.83% Stanford CDP California 5,711 2,381 41.69% Tangier town Virginia 250 66 26.40% Mason village Wisconsin 21 5 23.81% Ocean Beach village New York 64 14 21.88% Sand City city California 132 28 21.21% Isla Vista CDP California 8,360 1,642 19.64% Unity Village village Missouri 153 29 18.95% Hunter city Kansas 31 5 16.13% Crested Butte town Colorado 1,096 176 16.06% Davis city California 31,165 4,493 14.42% Rocky Ridge town Utah 160 23 14.38% Pelican city Alaska 77 11 14.29% Key West city Florida 14,611 1,856 12.70% Saltaire village New York 24 3 12.50% Keenes village Illinois 41 5 12.20% Longville city Minnesota 42 5 11.90% Stock Island CDP Florida 2,152 250 11.62% Goodland CDP Florida 74 8 10.81% Agenda city Kansas 28 3 10.71% Volant borough Pennsylvania 56 6 10.71% Tenakee Springs city Alaska 39 4 10.26% Tumacacori-Carmen C Arizona 199 20 10.05% Bearcreek town Montana 52 5 9.62% Briny Breezes town Florida 84 8 9.52% Barada village Nebraska 21 2 9.52% Layton city Florida 117 11 9.40% Evansville CDP Alaska 22 2 9.09% Nimrod city Minnesota 22 2 9.09% Nimrod city Minnesota 22 2 9.09% San Geronimo CDP California 245 22 8.98% Smith Island CDP Maryland 148 13 8.78% Laie CDP Hawaii 2,103 176 8.37% Hickam Housing CDP Hawaii 2,386 196 8.21% Slickville CDP Pennsylvania 112 9 8.04% Laughlin AFB CDP Texas 1,150 91 7.91% Minidoka city Idaho 38 3 7.89% Sykeston city North Dakota 51 4 7.84% Shipshewana town Indiana 310 24 7.74% Playita comunidad (Sa Puerto Rico 145 11 7.59% Dillard city Georgia 94 7 7.45% Putnam town Oklahoma 27 2 7.41% Fire Island CDP New York 191 14 7.33% Shorewood Hills village Wisconsin 779 57 7.32% Grenora city North Dakota 97 7 7.22% Buffalo Gap town South Dakota 56 4 7.14% Corvallis city Oregon 23,475 1,669 7.11% Boulder city Colorado 53,828 3,708 6.89% Gunnison city Colorado 2,825 189 6.69% Chistochina CDP Alaska 30 2 6.67% Grand Canyon Village Arizona 1,059 70 6.61% P. -

Yiannis N. Krallis Director General 11/29/2007 1

CHIPITACHIPITA RussiaRussia Yiannis N. Krallis Director General 1 11/29/2007 BACKGROUNDBACKGROUND • Chipita is a Greek origin multinational Company producing and commercializing packed flour based snacks such as: croissants, cakes and bread chips with turnover in excess of 1.5 billion Euro. • Established in 1973, Chipita brands are presented in more than 35 countries with production facilities in Greece, Russia, Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Mexico, Portugal, Egypt, the leader in all markets where present. • The main international umbrella brand is 7Days. 11/29/2007 2 COMPANYCOMPANY PROFILEPROFILE As of September 1st, 2006, Chipita merged with: ¾ DELTA, Number One in the diary industry ¾ GOODY`S, Number One in the foodservice industry, and ¾ GENERAL FROZEN FOODS “BARBA STATHIS”, Number One in the frozen food industry to establish VIVARTIA - Number One food company in Greece, ranking 35th in Europe with 35 factory units throughout 16 countries, and over 13 000 employees. 11/29/2007 3 BACKGROUNDBACKGROUND • In Russia, Chipita is a Leader of croissants under 7Days brand (with almost 80% market share), presented in main soft cakes segments. • Chipita manufactures 50 SKUs mainly croissants, cakes, pastes and salted snacks; and contracts for TANDER and DANONE. • Chipita Russia employs 750 people • Business activities: all Russia regions, • Commercial companies in: Ukraine, Byelorussia, • Exports activities: Serbia, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland, Hungary • Production facilities located in Saint Petersburg. 11/29/2007 4 CHIPITACHIPITALOGISTICS RUSSIARUSSIA Can one explain how a small, by the vast, Russian Geography Standards Company, can survive this Supply Chain and Logistics Marathon? We have been accused of bad service, of low deliveries ratios, we have even been de-listed from KA at times. -

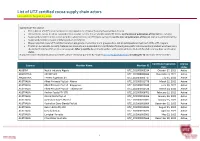

Board Date Bank Group Window Country Loan Type Project Amount

MDB Voting record December 2013 Bank US Env. Board Date Window Country Loan Type Project Amount Reason Code Group Position Category Qinghai Delingha Concentrated Solar 2-Dec-13 ADB ADB China Loan Thermal Power Plant $150.00 Abstain Does not meet BHN criteria. 8, 36 B Yunnan Sustainable Road Maintenance 2-Dec-13 ADB ADB China Loan Sector project $80.00 Abstain Does not meet BHN criteria. 8, 36 B Java–Bali 500-Kilovolt Power 2-Dec-13 ADB ADB Indonesia Loan Transmission Crossing Project $224.00 Support 62 A 2-Dec-13 WB IFC Russia Blend Fuyao Russia $50.00 Support B Chipita Gida Uritim Anonim Sirketi fo 2-Dec-13 WB IFC Turkey Loan the Chipita Turkey Project $14.40 Support B Project for Food Security Consolidation through Development of Irrigation 3-Dec-13 AFDB ADF Mali Blend Farming (PRESA/DCI) $53.98 Support B Urban–Rural Integration Water 3-Dec-13 ADB ADB China Loan Distribution Project $100.00 Support Meets BHN criteria. 7 B Business Climate Improvement and 3-Dec-13 AFDB ADF Chad Blend Economic Diversification Project $8.83 Support C Project includes local content 3-Dec-13 IDB IIC Uruguay Loan Fingano S.A. and Vengano S.A. $10.00 Abstain requirements. 1 B Nacala Road Corridor Development 3-Dec-13 AFDB ADF Regional Blend Project - Phase IV $71.95 Support 62 A Non- Combined 2013-2017 Country Strategy 3-Dec-13 AFDB AFDF Niger Financial Paper and Portfolio Review $0.00 Support N/A Adobe Social Mezzanine Fund I Limited 3-Dec-13 IDB IIC Mexico Equity Partnership $2.50 Support FI Banco Santander (México) S.A., 3-Dec-13 IDB IIC Mexico Loan Institución -

Greece Retail Foods

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Voluntary - Public Date: 6/27/2018 GAIN Report Number: IT1819 Greece Post: Rome Retail Foods Report Categories: Retail Foods Approved By: Fred Giles Prepared By: Dimosthenis Faniadis Report Highlights: In 2017, value sales of grocery retailers in Greece declined by 2.3 percent to $19.7 billion. The effects of the recession were still evident with low disposable incomes, low consumer confidence and high unemployment; yet the economy seemed to march towards stability. This was mirrored in retailing, as consumption began to pick up gradually. This report overviews the characteristics of Greek retail outlets and how best to place U.S. products in the Greek market. General Information: SECTION I. MARKET SUMMARY Overview Greece is the seventeenth largest economy in EU-28, accounting for 1.2 percent of the EU’s GDP for 2017, the same as Romania and Czech Republic. After a prolonged depression, the economy stabilized in 2017, and Greek GDP is estimated to grow approximately 1.0 percent, and 2.5 percent in 2018. Greece has a capitalist economy with a public sector accounting for about 40 percent of GDP, with tourism providing 18 percent of GDP. Greece is a major beneficiary of EU aid, equal to about 3.3 percent of annual GDP. With a population of 11 million and a gross domestic product (GDP) of approximately $204 billion, Greece is a relatively small country. Greece imports significantly more food and beverages than it exports and is reliant on imports to meet the demands of consumers for food products. -

The Western Balkans

������� ����������� ������� ������ ������� �������������� ������� ������ �������� The Western Balkans: ������� ������� ������ ����������� ������� ������� �������� Europe’s Next High-Value Location for Manufacturers ������� ����� ���������� ������ ����������� ��� ���������� �������� ��� ������� ��������� ������ r Now is a strategic time to invest in the Western Balkans r A new study of current investors analyzes operating costs and conditions r The European Investor Outreach Program (EIOP) helps investors consider their options and plan site visits ����������������� ���������������� As the EU expands, the focus is on the Western Balkans ������������������������� As the last frontier amid a rapidly integrating continent, the Western Balkans has emerged as Europe’s next high-growth destination for foreign direct investment (FDI). ���������������� ���� ����������������������� The region, now directly adjacent to the EU’s expanding border, has attracted the focus ���������������� of the leadership of the European Commission. It is expected that countries of the Western Balkans will enjoy membership in the EU within five to ten years. As has been demonstrated in the economic booms of recently acceded EU member countries, the period leading up to full EU integration is a strategic time for forward-looking investors to maximize their opportunity. An insiders’ perspective from current investors A recent benchmarking and competitiveness study* conducted by the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) of the World Bank Group substantiates -

The Humane League and Coalition Partners in the Fall of 2017

THL’s Reporting of Financials (2020) This document contains responses written by the charity. ACE has made no content changes other than the removal of confidential information. Program 1 Program name: Animal Welfare Campaigns - US (includes Corporate Engagement) Program expenses (2019): $1,936,811 Proportion of expenses that go to non-staff costs (2019): 33% In addition to staff time, these include expenses related to our broiler welfare and cage-free accountability campaign tactics, including PR stunts, grassroots tactics, advertisements (both digital and physical), campaign materials, travel for corporate meetings, and a coalition retreat. Program expenses (first 6 months of 2020): $671,898 Proportion of expenses that go to non-staff costs (first 6 months of 2020) 6% In addition to staff time, these include expenses related to our broiler welfare campaign tactics, including grassroots tactics, advertisements (both digital and physical), campaign materials, travel for corporate meetings, and a coalition retreat. Approximate number of staff hours invested (2019): 38,722 Approximate number of staff hours invested (first 6 months of 2020): 18,882 Approximate number of volunteer hours invested (2019): We do not track volunteer engagement by hour and we don't have a way to provide a meaningful estimate. Approximate number of volunteer hours invested (first 6 months of 2020): We do not track volunteer engagement by hour and we don't have a way to provide a meaningful estimate. Most important outcomes/accomplishments (2019 and the first 6 months -

Case No COMP/M.5644 - KRAFT FOODS / CADBURY

EN Case No COMP/M.5644 - KRAFT FOODS / CADBURY Only the English text is available and authentic. REGULATION (EC) No 139/2004 MERGER PROCEDURE Article 6(1)(b) in conjunction with Art 6(2) Date: 06/01/2010 In electronic form on the EUR-Lex website under document number 32010M5644 Office for Publications of the European Union L-2985 Luxembourg EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 06/01/2010 SG-Greffe(2010) D/49 C (2010) 40 In the published version of this decision, some PUBLIC VERSION information has been omitted pursuant to Article 17(2) of Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 concerning non-disclosure of business secrets and MERGER PROCEDURE other confidential information. The omissions are ARTICLE 6(1)(b) DECISION IN shown thus […]. Where possible the information omitted has been replaced by ranges of figures or a CONJUNCTION WITH general description. ARTICLE 6(2) To the notifying party: Dear Sir/Madam, Subject: Case No COMP/M.5644 - Kraft Foods / Cadbury Notification of 9/11/2009 pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation No 139/20041 1. On 9 November 2009, the Commission received a notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation No 139/2004 ("the EC Merger Regulation") by which Kraft Foods Inc. (“Kraft”, USA) would acquire within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation sole control of Cadbury PLC ("Cadbury", United Kingdom) by way of a public tender offer for all issued shares. I. THE PARTIES 2. Kraft is a world-wide food and beverage company active in more than 150 countries with its headquarters in the USA and listed at the New York Stock Exchange. -

Economic and Social Council Distr.: General 12 March 2014

United Nations E/CN.3/2014/INF/1 Economic and Social Council Distr.: General 12 March 2014 Original: English/French/Spanish Statistical Commission Forty-fifth session 4-7 March 2014 List of delegations Liste des délégations Lista de las delegaciones Chair: Ms. Jil Matheson (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) Vice-Chairs: Mr. Jiantang Ma (China) Mr. Pablo Tactuk (Dominican Republic) Ms. Gabrielle Vukovich (Hungary) Rapporteur: Mr. Joseph Tedou (Cameroon) 14-26355 (E) 180314 *1426355* E/CN.3/2014/INF/1 Members Membres Miembros Country Representative Alternates Advisers Pays Représentant Suppléants Conseillers País Representante Suplentes Consejeros Angola Mr. Lukoki Quiboco Artur Mr. Agostinho Sardina Mr. Gilberto Gonçalves Ms. Sherly Luzia Gomes Antonio Ribeiro Chipita de Carvalho Barbados Mr. Joseph Goddard Ms. Juliette Rosita Riley Ms. Kereeta Nicole Whyte Mr. Aubrey Victor Brown Ms. Rosalind Gail Riley Brazil Mr. Antonio de Aguiar Mr. Guilherme de Aguiar Mr. Mauricio Fernando Dias Patriota Patriota Favero Mr. Sérgio Rodrigues dos Ms. Claudia Assaf Bastos Santos Rebello Ms. Marcia Maria Melo Quintslr Ms. Denise Britz do Nascimento Silva Bulgaria Mr. Stephan Tafrov Ms. Yuliana Angelova Cameroon Mr. Michel Tommo M. Joseph Tedou M. Barnabé Okouda Monthe China Mr. Xu Xianchun Mr. Du Weiqun Ms. Chen Yingzhu Mr. Liu Fujiang Mr. Zhao Yuncheng Mr. Leung Kwan Chi Stephen Ms. Di Wei Ms. Li Shuang Cuba Mr. Rodolfo Reyes Mr. Oscar León González Mr. Emilio González Soca Rodríguez Ms. Maria del Carmen Franco Mr. Alexander Rodríguez Suáres Rosada Czech Republic Mrs. Iva Ritschelová Ms. Edita Hrdá Ms. Candida Novák Horňáková Dominican Sr. Pablo Tactuk Sra. -

2015 Tbilisi

NATIONAL INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY CENTER OF GEORGIA SAKPATENTI 14(426) 2015 TBILISI INID CODES FOR IDENTIFICATION OF BIBLIOGRAPHIC DATA LIST OF CODES, IN ALPHABETIC SEQUENCE, AND THE CORRESPONDING (SHORT) NAMES OF STATES, OTHER ENTITIES AND INTERGOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS (WIPO STANDARD ST.3) INVENTIONS, UTILITY MODELS (10) Number of publication for application, which has been examined (54) Title of the invention AD Andorra for the Arab States of the Gulf (GCC) NE Niger (11) Number of patent and kind of document (57) Abstract AE United Arab Emirates GD Grenada NG Nigeria (21) Serial number of application (60) Number of examined patent document granted by foreign patent office, date from which patent AF Afghanistan GG Guernsey NI Nicaragua (22) Date of filing of the application has effect and country code (62) Number of the earlier application and in case of divided application, date of filing an AG Antigua and Barbuda GH Ghana NL Netherlands (23) Date of exhibition or the date of the earlier filing and the number of application, if any application AI Anguilla GI Gibraltar NO Norway (24) Date from which patent may have effect (71) Name, surname and address of applicant (country code) AL Albania GT Guatemala NP Nepal (31) Number of priority application (72) Name, surname of inventor (country code) AM Armenia GW Guinea- Bissau NR Nauru (32) Date of filing of priority application (73) Name, surname and address of patent owner (country code) AN Netherlands Antilles GY Guyana NZ New Zealand (33) Code of the country or regional organization allotting -

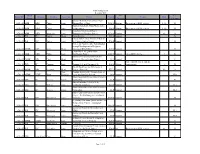

List of UTZ Certified Cocoa Supply Chain Actors List Valid On: August 25, 2021

List of UTZ certified cocoa supply chain actors List valid on: August 25, 2021 IMPORTANT TO KNOW: • This is the list of UTZ cocoa members certified against the Chain of Custody (Supply Chain Actors). • All members, except for those suspended (see column ‘License Status’), hold a valid UTZ license on the date of publication of this list (see subtitle). • Suspended members in this list are members whose licenses are effectively suspended on the date of publication of this list. Lists are updated monthly. • Suspended members cannot sell their product as certified. • Please note that many UTZ certified members are groups, multisite or multi-groups where not all participants are (yet) part of the UTZ program. • The list on our website currently features members who are suspended from certification following non-conformities as well as members who have been decertified from the UTZ certification program. After 3 months decertified members will be omitted from this list if they fail to renew their certification status. If you need more information about a member, please send your question by email to [email protected] including the ID and name of the member. Certificate Expiration License Country Member Name Member ID Date status ALGERIA Nestlé Industrie Algerie UTZ_CO1000009534 October 27, 2021 Active ARGENTINA ARCOR SAIC UTZ_CO1000005686 November 3, 2021 Active ARGENTINA Ferrero Argentina SA UTZ_CO1000002717 July 31, 2022 Active AUSTRALIA Allied Pinnacle Pty Ltd - Altona UTZ_CO1000012778 March 22, 2022 Active AUSTRALIA Allied Pinnacle Pty -

Deals in Greece 2017 One More Year of Low Investment Activity Mainly Driven by the Disposal of Non-Core Assets by the Systemic Banks

Deals in Greece 2017 One more year of low investment activity mainly driven by the disposal of non-core assets by the systemic banks February 2018 PwC M&A activity in 2017 • Greek companies attracted in total • Economic growth in 2017 was anaemic • The very few international deals give the € 5.5bn in 2017 , of which € 1.9bn were at less than 1.5%, with constrained tone that Greek assets are still not that raised through traded corporate bonds, liquidity and low investment activity attractive despite the asset value collapse € 1.6bn account for plain vanilla M&As, of the last 7 years just € 250mn for Share Capital Increases • Privatisation proceeds in 2017 were covered by strategic investors and driven by the 14 regional airports and • The top 20 M&As completed in Europe € 1.7bn through privatisation proceeds Trainose, reaching € 1.7bn in 2017 reached € 234 bn in value, of which 37% in Pharmaceuticals, 14% in • In 2017, 36 M&A deals of total value • The M&A market in Greece remained Retail and 8% in Manufacturing € 1.6bn were completed. The five largest very shallow, but as we are entering a deals amounted to € 1.2bn and period of growth, domestic • PwC is the leading global M&A financial represented divestments by the systemic transactions led by sectoral advisor in terms of number of M&A banks. Disposal of non core assets by the consolidators may be on the go deals, and the fourth M&A financial banks is the main phenomenon of the advisor in Europe in terms of deal value last few years, accounting for 75% in • In 2017 there was a shift