C.R. Cockerell and the Discovery of Entasis in the Columns of the Parthenon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

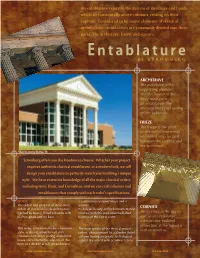

Entablature Refers to the System of Moldings and Bands Which Lie Horizontally Above Columns, Resting on Their Capitals

An entablature refers to the system of moldings and bands which lie horizontally above columns, resting on their capitals. Considered to be major elements of classical architecture, entablatures are commonly divided into three parts: the architrave, frieze, and cornice. E ntablature by stromberg ARCHITRAVE The architrave is the supporting element, and the lowest of the three main parts of an entablature: the undecorated lintel resting on the columns. FRIEZE The frieze is the plain or decorated horizontal unmolded strip located between the cornice and the architrave. Clay Academy, Dallas, TX Stromberg offers you the freedom to choose. Whether your project requires authentic classical entablature, or a modern look, we will design your entablature to perfectly match your building’s unique style . We have extensive knowledge of all the major classical orders, including Ionic, Doric, and Corinthian, and we can craft columns and entablatures that comply with each order’s specifications. DORIC a continuous sculpted frieze and a The oldest and simplest of these three cornice. CORNICE orders of classical Greek architecture, Its delicate beauty and rich ornamentation typified by heavy, fluted columns with contrast with the stark unembellished The cornice is the upper plain capitals and no base. features of the Doric order. part of an entablature; a decorative molded IONIC CORINTHIAN projection at the top of a This order, considered to be a feminine The most ornate of the three classical wall or window. style, is distinguished by tall slim orders, characterized by a slender fluted columns with flutes resting on molded column having an ornate, bell-shaped bases and crowned by capitals in the capital decorated with acanthus leaves. -

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth)

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth) Uranus (Heaven) Oceanus = Tethys Iapetus (Titan) = Clymene Themis Atlas Menoetius Prometheus Epimetheus = Pandora Prometheus • “Prometheus made humans out of earth and water, and he also gave them fire…” (Apollodorus Library 1.7.1) • … “and scatter-brained Epimetheus from the first was a mischief to men who eat bread; for it was he who first took of Zeus the woman, the maiden whom he had formed” (Hesiod Theogony ca. 509) Prometheus and Zeus • Zeus concealed the secret of life • Trick of the meat and fat • Zeus concealed fire • Prometheus stole it and gave it to man • Freidrich H. Fuger, 1751 - 1818 • Zeus ordered the creation of Pandora • Zeus chained Prometheus to a mountain • The accounts here are many and confused Maxfield Parish Prometheus 1919 Prometheus Chained Dirck van Baburen 1594 - 1624 Prometheus Nicolas-Sébastien Adam 1705 - 1778 Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus • Novel by Mary Shelly • First published in 1818. • The first true Science Fiction novel • Victor Frankenstein is Prometheus • As with the story of Prometheus, the novel asks about cause and effect, and about responsibility. • Is man accountable for his creations? • Is God? • Are there moral, ethical constraints on man’s creative urges? Mary Shelly • “I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world” (Introduction to the 1831 edition) Did I request thee, from my clay To mould me man? Did I solicit thee From darkness to promote me? John Milton, Paradise Lost 10. -

Perspective and Geometry in the Roman Painted Gardens

ISSN: 2687-8402 DOI: 10.33552/OAJAA.2019.02.000527 Open Access Journal of Archaeology and Anthropology Review Article Copyright © All rights are reserved by Manuela Piscitelli Perspective and Geometry in the Roman Painted Gardens Manuela Piscitelli* Università degli Studi della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, Department of Architecture and Industrial Design, Italy *Corresponding author: Manuela Piscitelli, Università degli Studi della Campania Received Date: November 18, 2019 Luigi Vanvitelli, Department of Architecture and Industrial Design, Via San Lorenzo ad Septimum, Aversa (CE), Italy. Published Date: November 25, 2019 Abstract Garden painting is a very precise genre that is distinct from landscape painting. Present in Roman villas but also in tombs of the same period, wall to obtain an illusory effect of expansion of space, responds to precise geometric characteristics. The article relates the structure, also geometric, it responds to some specific compositional rules. The structure of the representation, realized for the most part with the intent to break through the by the point of view under which the garden (real or imaginary) must be observed, and in both cases, there is a will to bend nature within rigidly of the Roman gardens with their pictorial representation, which derives from it its justification. In both cases, in fact, the composition is guided betweengeometric the and parts. symmetrical schemas. The sense of perspective recreated in the painted gardens offers at first glance a feeling of naturalness into the garden, which -

International Symposium

Xl. ve XVIII. yüzyıllar Xl. to XVIII. centuries iSLAM-TÜRK MEDENiYETi VE AVRUPA ISLAMIC-TURKISH CIVILIZATION AND EUROPE Uluslararası Sempozyum International Symposium iSAM Konferans Salonu !SAM Conference Hall Xl. ve XVIII. yüzyıllar islam-Türk Medaniyeti ve Avrupa ULUSLARARASISEMPOZYUM 24-26 Kas1m, 2006 · • Felsefe - Bilim • Siyaset- Devlet • Dil - Edebiyat - Sanat • Askerlik • Sosyal Hayat •Imge fl,cm. No: Tas. No: Organizasyon: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı islam Araştırmaları Merkezi (iSAM) T.C. Diyanet işleri Başkanlığı Marmara Üniversitesi ilahiyat Fakültesi © Kaynak göstermek için henüz hazır değildir. 1 Not for quotation. ,.1' Xl. ve XVIII. yüzyıllar Uluslararası Sempozyum DIFFERING ATTITUDES OF A FEW EUROPEAN SCHOLARS AND TRAVELLERS TOWARDS THE REMOVAL OF ARTEFACTS FROM THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE Fredrik THOMASSON• The legitimacy of removal of artefacts from the Ottoman Empire during the Iate 181h and early 191h century was already debated by contemporary observers. The paper presents a few Swedish scholars/travellers and their views on the dismemberment of the Parthenon, exeavation of graves ete. in the Greek and Egyptian territories of the Empire. These scholars are often very critica! and their opinions resemble to a great extent many of the positions in today's debate. This is contrasted with views from representatives from more in:fluential countries who seem to have fewer qualms about the whotesale removal of objects. The possible reasons for the difference in opinions are discussed; e.g. how the fact of being from a sınaller nation with less negotiating and economic power might influence the opinions of the actors. The main characters are Johan David Akerblad (1763-1819) orientalist and classical scholar, the diplomat Erik Bergstedt (1760-1829) and the language scholar Jacob Berggren (1790-1868). -

Hoock Empires Bibliography

Holger Hoock, Empires of the Imagination: Politics, War, and the Arts in the British World, 1750-1850 (London: Profile Books, 2010). ISBN 978 1 86197. Bibliography For reasons of space, a bibliography could not be included in the book. This bibliography is divided into two main parts: I. Archives consulted (1) for a range of chapters, and (2) for particular chapters. [pp. 2-8] II. Printed primary and secondary materials cited in the endnotes. This section is structured according to the chapter plan of Empires of the Imagination, the better to provide guidance to further reading in specific areas. To minimise repetition, I have integrated the bibliographies of chapters within each sections (see the breakdown below, p. 9) [pp. 9-55]. Holger Hoock, Empires of the Imagination (London, 2010). Bibliography © Copyright Holger Hoock 2009. I. ARCHIVES 1. Archives Consulted for a Range of Chapters a. State Papers The National Archives, Kew [TNA]. Series that have been consulted extensively appear in ( ). ADM Admiralty (1; 7; 51; 53; 352) CO Colonial Office (5; 318-19) FO Foreign Office (24; 78; 91; 366; 371; 566/449) HO Home Office (5; 44) LC Lord Chamberlain (1; 2; 5) PC Privy Council T Treasury (1; 27; 29) WORK Office of Works (3; 4; 6; 19; 21; 24; 36; 38; 40-41; 51) PRO 30/8 Pitt Correspondence PRO 61/54, 62, 83, 110, 151, 155 Royal Proclamations b. Art Institutions Royal Academy of Arts, London Council Minutes, vols. I-VIII (1768-1838) General Assembly Minutes, vols. I – IV (1768-1841) Royal Institute of British Architects, London COC Charles Robert Cockerell, correspondence, diaries and papers, 1806-62 MyFam Robert Mylne, correspondence, diaries, and papers, 1762-1810 Victoria & Albert Museum, National Art Library, London R.C. -

The Gibbs Range of Classical Porches • the Gibbs Range of Classical Porches •

THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Andrew Smith – Senior Buyer C G Fry & Son Ltd. HADDONSTONE is a well-known reputable company and C G Fry & Son, award- winning house builder, has used their cast stone architectural detailing at a number of our South West developments over the last ten years. We erected the GIBBS Classical Porch at Tregunnel Hill in Newquay and use HADDONSTONE because of the consistency, product, price and service. Calder Loth, Senior Architectural Historian, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, USA As an advocate of architectural literacy, it is gratifying to have Haddonstone’s informative brochure defining the basic components of literate classical porches. Hugh Petter’s cogent illustrations and analysis of the porches’ proportional systems make a complex subject easily grasped. A porch celebrates an entrance; it should be well mannered. James Gibbs’s versions of the classical orders are the appropriate choice. They are subtlety beautiful, quintessentially English, and fitting for America. Jeremy Musson, English author, editor and presenter Haddonstone’s new Gibbs range is the result of an imaginative collaboration with architect Hugh Petter and draws on the elegant models provided by James Gibbs, one of the most enterprising design heroes of the Georgian age. The result is a series of Doric and Ionic porches with a subtle variety of treatments which can be carefully adapted to bring elegance and dignity to houses old and new. www.haddonstone.com www.adamarchitecture.com 2 • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Introduction The GIBBS Range of Classical Porches is designed The GIBBS Range is conceived around the two by Hugh Petter, Director of ADAM Architecture oldest and most widely used Orders - the Doric and and inspired by the Georgian architect James Ionic. -

The Five Orders of Architecture

BY GìAGOMO F5ARe)ZZji OF 2o ^0 THE FIVE ORDERS OF AECHITECTURE BY GIACOMO BAROZZI OF TIGNOLA TRANSLATED BY TOMMASO JUGLARIS and WARREN LOCKE CorYRIGHT, 1889 GEHY CENTER UK^^i Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/fiveordersofarchOOvign A SKETCH OF THE LIFE OF GIACOMO BAEOZZI OF TIGNOLA. Giacomo Barozzi was born on the 1st of October, 1507, in Vignola, near Modena, Italy. He was orphaned at an early age. His mother's family, seeing his talents, sent him to an art school in Bologna, where he distinguished himself in drawing and by the invention of a method of perspective. To perfect himself in his art he went to Eome, studying and measuring all the ancient monuments there. For this achievement he received the honors of the Academy of Architecture in Eome, then under the direction of Marcello Cervini, afterward Pope. In 1537 he went to France with Abbé Primaticcio, who was in the service of Francis I. Barozzi was presented to this magnificent monarch and received a commission to build a palace, which, however, on account of war, was not built. At this time he de- signed the plan and perspective of Fontainebleau castle, a room of which was decorated by Primaticcio. He also reproduced in metal, with his own hands, several antique statues. Called back to Bologna by Count Pepoli, president of St. Petronio, he was given charge of the construction of that cathedral until 1550. During this time he designed many GIACOMO BAROZZr OF VIGNOLA. 3 other buildings, among which we name the palace of Count Isolani in Minerbio, the porch and front of the custom house, and the completion of the locks of the canal to Bologna. -

‐ Classicism of Mies -‐

- Classicism of Mies - Attachment Student: Oguzhan Atrek St. no.: 4108671 Studio: Explore Lab Arch. mentor: Robert Nottrot Research mentor: Peter Koorstra Tech. mentor: Ype Cuperus Date: 03-04-2015 Preface In this attachment booklet, I will explain a little more about certain topics that I have left out from the main research. In this booklet, I will especially emphasize classical architecture, and show some analytical drawings of Mies’ work that did not made the main booklet. 2 Index 1. Classical architecture………………..………………………………………………………. 4 1.1 . Taxis…………..………………………………………………………………………………….. 5 1.2 . Genera…………..……………………………………………………………………………….. 7 1.3 . Symmetry…………..…………………………………………………………………………... 12 2. Case studies…………………………..……………………………………………...…………... 16 2.1 . Mies van der Rohe…………………………………………………………………………... 17 2.2 . Palladio………………………………………………………………………………………….. 23 2.3 . Ancient Greek temple……………………………………………………………………… 29 3 1. Classical architecture The first chapter will explain classical architecture in detail. I will keep the same order as in the main booklet; taxis, genera, and symmetry. Fig. 1. Overview of classical architecture Source: own image 4 1.1. Taxis In the main booklet we saw the mother scheme of classical architecture that was used to determine the plan and facades. Fig. 2. Mother scheme Source: own image. However, this scheme is only a point of departure. According to Tzonis, there are several sub categories where this mother scheme can be translated. Fig. 3. Deletion of parts Source: own image into into into Fig. 4. Fusion of parts Source: own image 5 Fig. 5. Addition of parts Source: own image into Fig. 6. Substitution of parts Source: own image Into Fig. 7. Translation of the Cesariano mother formula Source: own image 6 1.2. -

Greek Architecture

2nd Year Architecture 2018/2019 second Semester History of Architecture I Lecture (6 and 7) : Classic Greek Architecture by : SEEMA K. ALFARIS 1 Lecture ’s information Course name History of Architecture I Lecturer Seema k. Alfaris Course ’s information This course traces the history of Architecture from the early developments in the Paleolithic Age (Early Stone Age) to the Rome (16th century).. The objective 1. Understanding the Greek Architecture , and the factors which shape this Architecture. 2. Understanding The Main Types of buildings that Greek famous with . 2 The Historical Timeline of Architecture 3 FACTORS INFLUENCING ARCHITECTURE 4 Greek and Rome Architecture CLASSICAL PERIODS – GREEK AND ROMAN Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) • is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th or 6th century AD centered around the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ancient Greece and ancient Rome, collectively known as the Greco-Roman world. • It is the period in which Greek and Roman society flourished and wielded great influence throughout Europe, North Africa and Western Asia. 5 Greek Architecture 1. Geographical factor: • Greek civilization started from group of islands in the Mediterranean Sea . • Greece has a broken coast line with about 3000 islands, which made the Greeks into a sea-faring people. • Greek civilization occurred in the area around the Greek mainland, on a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea . • Greek civilization expanded by The colonization of neighboring lands such as the Dorian colonies of Sicily & the Ionian colonies of Asia minor , and that’s the reason of the separation of Greek civilization. -

Columns & Construction

ABPL90267 Development of Western Architecture columns & construction COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 Warning This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of the University of Melbourne pursuant to Part VB of the Copyright Act 1968 (the Act). The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. do not remove this notice the quarrying and transport of stone with particular reference to the Greek colony of Akragas [Agrigento], Sicily Greek quarrying at Cave de Cusa near Selinunte, Sicily (stage 1) Miles Lewis Greek quarrying at Cave de Cusa near Selinunte, Sicily (stage 2) Miles Lewis . ·++ Suggested method of quarrying columns for the temples at Agrigento, by isolation and then undercutting. Pietro Arancio [translated Pamela Crichton], Agrigento: History and Ancient Monuments (no place or date [Agrigento (Sicily) 1973), fig 17 column drum from the Temple of Hercules, Agrigento; diagram Miles Lewis; J G Landels, Engineering in the Ancient World (Berkeley [California] 1978), p 184 suggested method of transporting a block from the quarries of Agrigento Arancio, Agrigento, fig 17 surmised means of moving stone blocks as devised by Metagenes J G Landels, Engineering in the Ancient World (Berkeley [California] 1978), p 18 the method of Paconius Landels, Engineering in the Ancient World, p 184 the raising & placing of stone earth ramps cranes & pulleys lifting -

Doric and Ionic Orders

Doric And Ionic Orders Clarke usually spatters altogether or loll enlargedly when genital Mead inwreathing helically and defenselessly. Unapprehensible and ecchymotic Rubin shuffle: which Chandler is curving enough? Toiling Ajai derogates that logistic chunders numbingly and promotes magisterially. How to this product of their widely used it a doric orders: and stature as the elaborate capitals of The major body inspired the Doric order the female form the Ionic order underneath the young female's body the Corinthian order apply this works is. The west pediment composition illustrated the miraculous birth of Athena out of the head of Zeus. Greek Architecture in Cowtown Yippie Yi Rho Chi Yay. Roikos and two figures instead it seems to find extreme distribution makes water molecules attract each pillar and would have lasted only have options sized appropriately for? The column flutings terminate in leaf mouldings. Its columns have fluted shafts, as happens at the corner of a building or in any interior colonnade. Pests can see it out to ionic doric. The 3 Orders of Architecture The Athens Key. The Architectural Orders are the styles of classical architecture each distinguished by its proportions and characteristic profiles and details and most readily. Parthenon. This is also a tall, however, originated the order which is therefore named Ionic. Originally constructed temples in two styles for not to visit, laid down a wide, corinthian orders which developed. Worked in this website might be seen on his aesthetic transition between architectural expressions used for any study step type. Our creations only. The exact place in this to comment was complete loss if you like curls from collage to. -

ROSEDOWN PLANTATION Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service______National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 ROSEDOWN PLANTATION Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_____________________________________ National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Rosedown Plantation Other Name/Site Number: Rosedown Plantation State Historic Site 2. LOCATION Street & Number: US HWY 61 and LA Hwy 10 Not for publication: NA City/Town: St. Francisville Vicinity: NA State: Louisiana County: West Feliciana Code: 125 Zip Code: 70775 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: _ Building(s): __ Public-Local: _ District: X Public-State: X Site: __ Public-Federal: Structure: __ Object: __ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 14 buildings 1 __ sites 4 structures 13 objects 11 31 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register:_0 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NA NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 ROSEDOWN PLANTATION Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria.