The Malign Hand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ASA ECONOMIC SOCIOLOGY SECTION NEWSLETTER ACCOUNTS Volume 9 Issue 1 Spring 2010

ASA ECONOMIC SOCIOLOGY SECTION NEWSLETTER ACCOUNTS Volume 9 Issue 1 Spring 2010 Section Chair’s Introduction 2009‐10 Editors Jiwook Jung T Kim Pernell Sameer Srivastava The events of the last year and a half, or two if you were watching things Harvard University closely, have led many to question whether the economy operates as most everyone understood it to operate. The Great Recession has undermined many shibboleths of economic theory and challenged the idea that free markets regulate themselves. The notion that investment bankers and titans of industry would never take risks that might put the economy in jeopardy, because they would pay the price for a collapse, now seems Inside this Issue quaint. They did take such risks, and few of them have paid any kind of price. The CEOs of the leading automakers were chided for using private Markets on Trial: Progress and jets to fly to Washington to testify before Congress, and felt obliged to Prognosis for Economic Sociology’s Response to the Financial Crisis— make their next trips in their own products, but the heads of the investment Report on a Fall 2009 Symposium banks that led us down the road to perdition received healthy bonuses this by Adam Goldstein, UC Berkeley year, as they did last year. The Dollar Standard and the Global ProductionI System: The In this issue of Accounts, the editors chose to highlight challenges to Institutional Origins of the Global conventional economic wisdom. First, we have a first-person account, Financial Crisis by Bai Gao, Duke from UC-Berkeley doctoral candidate Adam Goldstein, of a fall Kellogg Book Summary and Interview: School (Northwestern) symposium titled Markets on Trial: Sociology’s David Stark’s The Sense of Response to the Financial Crisis. -

Cass City Chronicle

CASS CITY CHRONICLE < q ~.q, r _ ~.~--- .............. .. ......... ,, VOLUME 32, NUMBER 30. CASS CITY, MICHIGAN, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 22, 1937. EIGHT PAGES. East Central Dist. Will Speak at East Central District Meeting Fremont Twp. U. S. Senator and Circuit Judge Receive O¢~Or of r ..... ITuscda Solons E0nventon iiere Woman injured i Entertain3 o Their, on Oct. 26-27 by Two Robbers Huron Co. Brethren Sessions Will Be Held at Three Visit Farm on "Po- Boards Discuss Mutual # ,$ Presbyterian Church and taro Buying Errand and Problems and Attend a the School Auditorium. Rob Housewife of $10.00. Banquet Monday Night. _ The Tuscola County Federation Mrs. Carl Bednaryczk was knocked unconscious Wednesday Huron county supervisors were of Women's Clubs will be the host- guests of the Tuscola board of morning at her home, 7½ miles esses of the East Central district supervisors on Monday afternoon south of Care, on M-85, by two convention which will be held in and evening'. In the afternoon, at Cuss City next Tuesday and robbers who entered her home and stole $10. the court house, they discussed Wednesday, October 26 and 27. mutual problems and the method The district includes the counties Three men drove up to the Bed- naryczk home shortly before noon of solving; them in the two coun- of Genese% Gratiot, Huron, La- ,ties. Sunday hunting, hospitaliza- peer, Macomb, Saginaw, Sanilac, and asked Mrs. Bednaryczk if she had any potatoes to sell. She re- tion and welfare were the subjects St. Clair and Tuscola. that received the most attention. plied she had, and when requested The convention opens at 9:00 a. -

The Future of Money: from Financial Crisis to Public Resource

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Mellor, Mary Book — Published Version The future of money: From financial crisis to public resource Provided in Cooperation with: Pluto Press Suggested Citation: Mellor, Mary (2010) : The future of money: From financial crisis to public resource, ISBN 978-1-84964-450-1, Pluto Press, London, http://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/30777 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/182430 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

Fund More Study Kamehameha Schools/Bishop Estate, Including State Rep

NOTICE TO HAWAII MARINE READERS We hope you will enjoy this special readers during the holiday season when This special edition, published each edition of the Windward Sun Press, the Hawaii Marine is not published. year, is in no way connected to the Navy created especially for Hawaii Marine Aiituctaie duce or the U.S. government. Windward Sun ress VOL. XXX NO. 33 2s rents/Voluntary Payment For Home Delivery: One Dollar Per Four Week Period WEEK OF JANUARY 4-10, 1990 BRIEFLY Corps to help Wetlands meeting KANEOHE - Representatives from the fund more study Kamehameha Schools/Bishop Estate, including state Rep. Henry Peters, will address the sale of the Heeia meadowlands at the next Community Hour sponsored by state Rep. Terrance Tom. on marsh levee The meeting will be held at 7 p.m. on Jan. 10 in Room D-6 at Benjamin Parker Elementary By MARK DOYLE School. News Editor "At our last Community Hour, the absence of Bishop Estate in discussions regarding the sale KAILUA - Two full years after of the Heeia meadowlands was of some concern," Kailua was hit hard by the 1987 New Tom said. Year's Eve Flood, the U.S. Army However, their willingness to be present at the Corps of Engineers has said it needs next meeting "demonstrates their sincere desire yet another year to study flood con- to work with our community." Tom said. trol improvements for the levee in "This will be a good step toward building a Kawainui Marsh. more positive relationship between the residents According to corps spokesperson of our community and the people at Kamehameha Elsie Smith, the corps received ver- Schools/Bishop Estate," he added. -

Video Resources Feature Films Boiler Room

Video Resources Feature Films Boiler Room. New Line Cinema, 2000.A college dropout, attempting to win back his father's high standards he gets a job as a broker for a suburban investment firm, which puts him on the fast track to success, but the job might not be as legitimate as it once appeared to be. Margin Call. Before the Door Pictures, 2011. Follows the key people at an investment bank, over a 24- hour period, during the early stages of the 2008 financial crisis. The Wolf of Wall Street. Universal Pictures, 2013. Based on the true story of Jordan Belfort, from his rise to a wealthy stock-broker living the high life to his fall involving crime, corruption and the federal government. The Big Short. Paramount Pictures,2015. In 2006-7 a group of investors bet against the US mortgage market. In their research they discover how flawed and corrupt the market is. The Last Days of Lehman Brothers. British Broadcasting Corporation, 2009. After six months' turmoil in the world's financial markets, Lehman Brothers was on life support and the government was about to pull the plug. Documentaries Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room. Jigsaw Productions, 2005. A documentary about the Enron Corporation, its faulty and corrupt business practices, and how they led to its fall. Inside Job. Sony Pictures Classics, 2010. Takes a closer look at what brought about the 2008 financial meltdown. Too Big to Fail. HBO Films, 2011. Chronicles the financial meltdown of 2008 and centers on Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson. Money for Nothing: Inside the Federal Reserve. -

Education Election

SELF-DEFENSE BAND CONTESTS Junior learns karate Band program attends for self-defense two different purposes marching festivals Page 6 Page 12 THE VOL. 94 NO. 3 • HAYS HIGH SCHOOL UIDO 2300 E. 13th ST. • HAYS, KAN. 67601 G www.hayshighguidon.comNOVEMBER 14, 2019 N SCHOOL LIFE HONOR STUDENTS National Honor Society Education Election hosts ceremony, inducts USD 489 completes summer renovations 38 new juniors, seniors By Alicia Feyerherm value to the students.” By Michaela Austin Hays High Guidon After the guest speaker, Hays High Guidon NHS officers explained On Nov. 5, the communi- National Honor Soci- the principles of NHS ty voted for four new mem- ety Induction was held and lit candles represent- bers to be a part of the USD at 7:30 p.m. on Nov. ing the four fundamen- 489 Board of Education. 6 in the Lecture Hall. tal virtues of the society: There was a total of nine The ceremony be- Character, Scholarship, candidates who ran for the gan with the Hays High Leadership and Service. position. The candidates Quartet, comprised of The inductees recited included Paul Adams, juniors Alisara Arial, the NHS pledge and then Cole Engel, Alex Herman, Tom Drabkin, Ash- walked across the stage. ley Vilaysing and soph- Lori Ann Hertel, Jessica Each inductee signed the omore Sydney Witt- Moffitt, Luke Oborny, NHS book and received korn, performing. Craig Pallister, Allen Park a certificate and pin. Following their perfor- and Tammy Wellbrock. The new members of mance, NHS president The four new mem- NHS include the following: Nathan Erbert welcomed bers are Hertel, Pallis- Seniors: everyone and introduced ter, Park and Wellbrock. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Playing Along Infinite Rivers: Alternative Readings of a Malay State Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/70c383r7 Author Syed Abu Bakar, Syed Husni Bin Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Playing Along Infinite Rivers: Alternative Readings of a Malay State A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Syed Husni Bin Syed Abu Bakar August 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Hendrik Maier, Chairperson Dr. Mariam Lam Dr. Tamara Ho Copyright by Syed Husni Bin Syed Abu Bakar 2015 The Dissertation of Syed Husni Bin Syed Abu Bakar is approved: ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements There have been many kind souls along the way that helped, suggested, and recommended, taught and guided me along the way. I first embarked on my research on Malay literature, history and Southeast Asian studies not knowing what to focus on, given the enormous corpus of available literature on the region. Two years into my graduate studies, my graduate advisor, a dear friend and conversation partner, an expert on hikayats, Hendrik Maier brought Misa Melayu, one of the lesser read hikayat to my attention, suggesting that I read it, and write about it. If it was not for his recommendation, this dissertation would not have been written, and for that, and countless other reasons, I thank him kindly. I would like to thank the rest of my graduate committee, and fellow Southeast Asianists Mariam Lam and Tamara Ho, whose friendship, advice, support and guidance have been indispensable. -

JANUARY 23, 1969 a Wise Move, It Should Not Have Been Necessary the Penn State Blue Band Members Apologized Educational Psychology Dept

Black s Turn to Harrisbur g For Support on 13 Requests By WILLIAM EPSTEIN "" black professors at Perm Stale. Collegian Managing Editor • _ • • _ The Douglas A>>oct;iUon rejected || ^^ || - | ^ J I« High-ranking state legis- rvis Cites Unive rsity budget ^;l;:^^ lators threatened yesterday to * ^^ o( misconceptions." ^ withhold the University's ap- propriations unless black en- rollment is increased. As 'String To Pull' for Action £H' ":Si offic e. -3= The threat came as TO members gation of the Universll y's n°nc. Irv's •«»'<> • He didn l hesitate Shafcr' Nearly 100 blacks filed quietly of the Douglas Association traveled when asked if the University's policies on admissions and faculty Kline said he would refuse to into Old Main. Each carrying one to Harrisburg to gather political budget request would play a role hiring. Irvis said he wants proof support funds (or " any university or two bricks, they built a wall support for their request that Penn " that the Administration i s in "getting things done. wisely State step up its" recruiting of bl ack that is not spending money topped by one black brick. attempting to open the University "Now >ou 're Retting lien- the for all the people of PcnnsyUai.ia." ,_ ^.^ sudents. wnl sj m,,olj J.c(1 to more blacks. j ,caI.t 0f wiiat i mcan w i,cn i ^ ^ No Avoiding llarrisliurg ihc end of communication between Irvis Pledges Support —He will visit University Park sa-v thcre are certain .strings that " Rick Collins, president of the the blacks and the Administrat ion . -

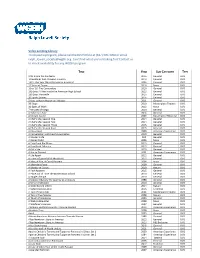

Video Lending Library to Request a Program, Please Call the RLS Hotline at (617) 300-3900 Or Email Ralph Lowell [email protected]

Video Lending Library To request a program, please call the RLS Hotline at (617) 300-3900 or email [email protected]. Can't find what you're looking for? Contact us to check availability for any WGBH program. TITLE YEAR SUB-CATEGORY TYPE 9/11 Inside the Pentagon 2016 General DVD 10 Buildings that Changed America 2013 General DVD 1421: The Year China Discovered America? 2004 General DVD 15 Years of Terror 2016 Nova DVD 16 or ’16: The Contenders 2016 General DVD 180 Days: A Year inside the American High School 2013 General DVD 180 Days: Hartsville 2015 General DVD 20 Sports Stories 2016 General DVD 3 Keys to Heart Health Lori Moscas 2011 General DVD 39 Steps 2010 Masterpiece Theatre DVD 3D Spies of WWII 2012 Nova DVD 7 Minutes of Magic 2010 General DVD A Ballerina’s Tale 2015 General DVD A Certain Justice 2003 Masterpiece Mystery! DVD A Chef’s Life, Season One 2014 General DVD A Chef’s Life, Season Two 2014 General DVD A Chef’s Life, Season Three 2015 General DVD A Chef’s Life, Season Four 2016 General DVD A Class Apart 2009 American Experience DVD A Conversation with Henry Louis Gates 2010 General DVD A Danger's Life N/A General DVD A Daring Flight 2005 Nova DVD A Few Good Pie Places 2015 General DVD A Few Great Bakeries 2015 General DVD A Girl's Life 2010 General DVD A House Divided 2001 American Experience DVD A Life Apart 2012 General DVD A Lover's Quarrel With the World 2012 General DVD A Man, A Plan, A Canal, Panama 2004 Nova DVD A Moveable Feast 2009 General DVD A Murder of Crows 2010 Nature DVD A Path Appears 2015 General -

The Ascent of Money: a Financial History of the World Author: Niall Ferguson Publisher: Penguin Group Date of Publication: November 2008 ISBN: 9781594201929 No

The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World Author: Niall Ferguson Publisher: Penguin Group Date of Publication: November 2008 ISBN: 9781594201929 No. of Pages: 432 Buy This Book [Summary published by CapitolReader.com on April 23, 2009] Click here for more political and current events books from Penguin. About The Author: Niall Ferguson is one of Britain’s most renowned historians. He teaches history at both Harvard and Oxford. He is also the author of numerous bestsellers including The War of the World. In addition, Ferguson has brought economics and history to a wider audience through several highly-popular TV documentary series and also through his frequent newspaper and magazine articles. General Overview: Bread, cash, dough, loot: Call it what you like, it matters. To Christians, love of it is the root of all evil. To generals, it’s the sinews of war. To revolutionaries, it’s the chains of labor. But in The Ascent of Money, Niall Ferguson shows that finance is in fact the foundation of human progress. What’s more, he reveals financial history as the essential backstory behind all history. The evolution of credit and debt, in his view, was as important as any technological innovation in the rise of civilization. * Please Note: This CapitolReader.com summary does not offer judgment or opinion on the book’s content. The ideas, viewpoints and arguments are presented just as the book’s author has intended. - Page 1 Reprinted by arrangement with The Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc., from THE ASCENT OF MONEY by Niall Ferguson. -

February 2009

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Inland Empire Business Journal Special Collections & University Archives 2-2009 February 2009 Inland Empire Business Journal Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/iebusinessjournal Part of the Business Commons Recommended Citation Inland Empire Business Journal, "February 2009" (2009). Inland Empire Business Journal. 159. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/iebusinessjournal/159 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections & University Archives at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inland Empire Business Journal by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ...SiliiTID PAID A E **"""*"AUJO••SCH 1 DIGIT 916 Onwno,('·- \ IHGRlD nHJHOHV Ptmut ,,. I OR CURRfHI OCCUPAHI 6511 CRISTA PAlHA OR HUHIIHGIOH DEACH, CA 9264/ 6617 ourn 11.1 .... 1.1.11 ... 1•• 11,,,1,11 ... 11,,,,,111 ••• 1••• 11 ,,,1111 ... 1 \\\\\\ 0USJOoHI Jl l-01'1 VOLUME 21. UMBER 2 '52.00 February 200L) School for Autism Spectrum Disorders expands to AT DEADLINE meet the needs of the grO\\ing autistic population Special LeRo) Ha)nec., Center It \\a\ jU\t ll\C year\ ago that n----'T::::';J;;:::::.. 11111"'~F., Sections Appoints former Habitat LeRo) llaynes Center tkcided to open ,t clas,room to meet the 'Pl' Thr ( rtdit l'nsrs an Inland t.mptre for Humanit) controller as Opportumh? Quarttrl) Eronollllf cial need' of thL' grovv ing autistJL' nen chief financial officer Report population. The former controller for Focus is placed on the develop Pg. 3 Pg.J! I laoitat for llumantt) of Greater mg.