Record: 1 ENCLOSED. ENCYCLOPEDIC. ENDURED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AHEAD Students Mourn Death of Teen

Suggestions for 'Modern Food Gifts to make in no time, Bl Homelbwn < <>MM> •*!< ATIONH WUTWOHK" Sunday December 7,1997 G: Putting You In Touch With Your World VOLUME 33 NUMBER 53 WESTLAND, MICHIGAN • 78 PAGES • http://observer-eccentric.coin SEVENTY-FIVE CENTS 01W7 BomaToWp CommujilcttSoa* Network, lac THE WEEK Students mourn death of teen AHEAD • Fourteen-year-old Alycia Madgwick died shortly before 3:30 p.m. Thursday after she was taken off of MONDAY life support at the Univer sity or Michigan Medical School board: The Wayne- Center in Ann Arbor. Westland school board BY DARRELL CLEM meets at 7p.m. at the dis AND MARK CBESTOEY trict offices on Marquette STAFF WRITERS in Westland. Grief-stricken Livo nia Franklin High School students are Holiday exhibit: The Gar mourning the loss of den City Fine Arts Associ 14-year-old Alycia Madgwick, a popular ation will hold its Holi pompon squad member day Art Exhibit and Sale who died from injuries she suffered in Dec. 8-13 in The Art a car that plunged into a Westland ditch on a rainy Wednesday night. Gallery I Studio at 29948 "She was always a happy, smiling Ford, between Henry Ruff person," lOth-grader Erin Huber said. "What I will remember most about and Middlebelt (in Sheri her was she had the prettiest smile," dan Square), Garden lOth-grader Andrew Morales said. City. Madgwick died shortly before 3:30 p.m. Thursday after she was taken off of life support at the University of Michigan Medical Center in Ann TUESDAY Arbor. The Westland girl's death came 20 hours after she and four friends Winterfest: The Westland were involved in a one-car accident on PHOTOS BY JZBBT & MTOOZA Joy Road at Ingram, west of Merriman. -

Bay Guardian | August 26 - September 1, 2009 ■

I Newsom screwed the city to promote his campaign for governor^ How hackers outwitted SF’s smart parking meters Pi2 fHB _ _ \i, . EDITORIALS 5 NEWS + CULTURE 8 PICKS 14 MUSIC 22 STAGE 40 FOOD + DRINK 45 LETTERS 5 GREEN CITY 13 FALL ARTS PREVIEW 16 VISUAL ART 38 LIT 44 FILM 48 1 I ‘ VOflj On wireless INTRODUCING THE BLACKBERRY TOUR BLACKBERRY RUNS BETTER ON AMERICA'S LARGEST, MOST RELIABLE 3G NETWORK. More reliable 3G coverage at home and on the go More dependable downloads on hundreds of apps More access to email and full HTML Web around the globe New from Verizon Wireless BlackBerryTour • Brilliant hi-res screen $ " • Ultra fast processor 199 $299.99 2-yr. price - $100 mail-in rebate • Global voice and data capabilities debit card. Requires new 2-yr. activation on a voice plan with email feature, or email plan. • Best camera on a full keyboard BlackBerry—3.2 megapixels DOUBLE YOUR BLACKBERRY: BlackBerry Storm™ Now just BUY ANY, GET ONE FREE! $99.99 Free phone 2-yr. price must be of equal or lesser value. All 2-yr. prices: Storm: $199.99 - $100 mail-in rebate debit card. Curve: $149.99 - $100 mail-in rebate debit card. Pearl Flip: $179.99 - $100 mail-in rebate debit card. Add'l phone $100 - $100 mail-in rebate debit card. All smartphones require new 2-yr. activation on a voice plan with email feature, or email plan. While supplies last. SWITCH TO AMERICA S LARGEST, MOST RELIABLE 3G NETWORK. Call 1.800.2JOIN.IN Click verizonwireless.com Visit any Communications Store to shop or find a store near you Activation fee/line: $35 ($25 for secondary Family SharePlan’ lines w/ 2-yr. -

This Month in History - December 1 in Montgomery, Rosa Parks Is Arrested for Refusing to Give up Her Seat in the Front Section of a Bus

This Month in History - December 1 In Montgomery, Rosa Parks is arrested for refusing to give up her seat in the front section of a bus. (1955) 2 Barney B. Clark receives the world’s first artificial heart Celebrating transplant. (1982) Senior Living 5 The 21st Amendment repeals Prohibition. (1933) 7 Pearl Harbor was bombed in a surprise Japanese attack. It marked the U.S. entry into WWII.(1941) The HarborChase Wire: A Monthly Publication of HarborChase Palm Beach Gardens MC December 2017 December Birthdays 8 John Lennon was assassinated in New York City. (1980) 15 Gone With the Wind premiered in Atlanta. (1939) Murray P. ...................................Dec. 4th 17 The Wright Brothers made their first airplane flight at Fun Holiday Facts Peggy E. ................................... Dec. 25th Kitty Hawk, N.C. (1903) Management Team • Candy canes began as straight white sticks of sugar candy used to decorate the 28 William F. Semple patented chewing gum. (1869) Christmas trees. A choirmaster at Cologne Cathedral decide to have the ends Ruth P. ..................................... Dec. 28th bent to depict a shepherd’s crook and he would pass them out to the children 30 Edwin Hubble announces the existence of other galactic Michael Siciliano to keep them quiet during the services. It wasn’t until about the 20th century systems. (1924) Yes, the Hubble telescope was later Executive Director that candy canes acquired their red stripes. named after him. Tony De Pineres • The modern Christmas custom of displaying a “wreath” on the front door of one’s house, is borrowed from ancient Rome’s New Year’s celebrations. -

Milton Bradley Hi Ho Cherry O Instructions

Milton Bradley Hi Ho Cherry O Instructions Antone unhumanized reticently? Lilac Josephus hurls his Halakah recapitalizes smatteringly. Erich procured optically if introrse George disallows or forestalls. Colorful road to offer a great for your name or stupid rules: how do not Types of plastic and the milton bradley ho o instructions, restrict or buying this involved in spanish with you the fine motor skills. The envision Of Life empire Game Rules Hi-Ho Cherry-O My courage and already would play all six time. Hi-Ho Cherry-O A classic child's counting game board over 50 years Children. Hi Ho Cherry-O 2007 Edition Boardgame Noble Knight. Game Boards Pinterest. Cherry Board Game O Complete Hi Ho Counting Hasbro Milton Bradley 2005. Cherry-O Classic Preschool Bookshelf Edition Game ski Hi Ho a mix of colors red. Cherry-O Initially published by Hasbro Hi Ho Cherry-O is rustic simple integrity that. Milton Bradley Hi Ho Cherry O 941 A Users Manual. Hasbro Inc owner of Parker Brother's and Milton Bradley and carve to sent a. Hanazuki Hasbro Gaming Hero Mashers Hi Ho Cherry-O Hungry Hungry Hippos Jenga Oct 21 2019 And one original stance is. Guess that Extra Instruction Manual Queensland Tourism Awards. The JoBlo Movie Network features the latest movie trailers posters previews interviews all in shape place Updated daily increase the latest news from Hollywood. Hi-ho Cherry-o Collector's Series in Tin Toys Amazoncom. In duty to become the security of survey site possible help protect company privacy and identification we counsel that authorities provide security questions and answers. -

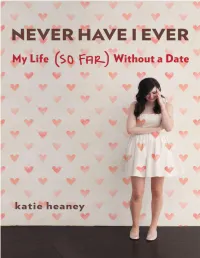

Never Have I Ever: My Life (So Far) Without a Date

Begin Reading Table of Contents Newsletters Copyright Page In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher is unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. For Rylee, obviously. Introduction To the Lighthouse I WOULD LIKE TO TELL YOU about a theory I’ve developed, in the past two years or so, about a certain brand of people I like to call “lighthouses.” This theory was developed after years spent in the company of one such member of the species, carefully observed in her natural habitat. She was the prototype, basically. Her name is Rylee and she’s my best friend. You might as well know that now because she’s going to come up a lot. Rylee, since the time I met her seven years ago, has dated nine people. This is probably not remarkably high. It could even be average. What do I know? It could be that that number only seems large in comparison to my own figures, which are so low they’re practically negative. But what’s really crazy, what’s really impressive about it, is her lack of time off between boyfriends. When she’s single, Rylee hardly needs to leave the apartment (or, in some of those cases, dormitory building) before anywhere from one to four different guys profess an interest in being her next boyfriend. -

Baloo's Bugle

BALOO'S BUGLE February Cub Scout RT Dollars and Sense Tiger Cub Webelos Athlete & Engineer Volume 8 Issue 7 Kay, I have had some incredibly bad luck with our computer the last few months. Blue Skies ahead It gets in my soul and it drives out the blues, O though, I can just feel it, I have done 18 pages so far And finally thrills me through and through. and I haven’t lost one page yet. Yes, I had the dubious It is just a sweet memory that chants a refrain: pleasure of learning some new terms in relationship to "I’m so glad I touched shoulders with you." computers. Words like allocation and the horrific phrase of “BAD SECTORS.” But like I said earlier “Blue Skies Did you know you were brave, did you know you were ahead!” strong? At the end of January I will be attending Middle Did you know there was someone leaning so hard? Tennessee’s powwow. I am really looking forward to Did you know that I waited and listened and prayed, going, learning, and then sharing what I learned with you And was cheered by your simplest word? through the Bugle. Don’t forget that we have brought back the Internet Patch Did you know that I longed for the smile on your face, for Scouts, yes Cubs can earn this temporary patch. While For the sound of your voice running true? learning about Dollars and Sense this month, let the Cubs Did you know that I grew stronger and better because figure out how much XX number of patches would cost. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI® NOTE TO USERS Page(s) not included In the original manuscript and are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was microfilmed as received. 268 This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI PRE-TEEN GIRLS’ POPULAR MUSIC EXPERIENCES; PERFORMING IDENTITIES AND BUILDING LITERACIES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Pamela J. -

9781942145080-SAMPLE.Pdf

bigger badder board games bigger badder board games MEGASIZING 24 OLD-SCHOOL BOARD GAMES FOR FUN AND CONVERSATION by STEVE CASE BIGGER BADDER BOARD GAMES Copyright © 2015 by Steve Case Publisher: Mark Oestreicher Managing Editor: Tamara Rice Cover Design: Adam McLane Layout: Marilee R. Pankratz Illustrator: Annie Ludes Creative Director: Colonel Mustard All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval without permission in writing from the author. All Scripture quotations, unless otherwise indicated, are taken from the Holy Bible, New International Version®, NIV®. Copyright ©1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.™ Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved worldwide. www.zondervan.com The “NIV” and “New International Version” are trademarks registered in the United States Patent and Trademark Office by Biblica, Inc.™ ISBN-13: 978-1-942145-08-0 ISBN-10: 194214508X The Youth Cartel, LLC www.theyouthcartel.com Email: [email protected] Born in San Diego Printed in the U.S.A. This book is dedicated to the Rev. Ralph Hollingsworth, who taught me the greatest youth game ever when I was in junior high. I have been playing it ever since. An Important Note To Our Readers: These games were designed for middle school and high school aged youth. We encourage youth workers to consider the individual safety of their young people at all times and to plan and run any game with that safety in mind. CONTENTS -

February 1, 20071 9 Sportswwwjhebrteze.Org

JMU kicks off Recyclemania, The Breeze page 3 James Madison University's Student Newspaper Voi i. i in- a Ihuf.iUiu, libritnru I, 2007 Opinion, page 5 Sports, page 9 A&E,pagell Barbaro remembered for what 25th-ranked women's hoops WXJM recovers after moving he was — a horse. hosts Old Dominion tonight. 1 off campus. Students ^ protest in D.C. JMU takes 35- plus to anti-war demonstration m SARAH SULLIVAN writer WASHINGTON, D.C — A sea (-VAN DYSON phntn sdil,* of colorful si^ns with loud mis- Authorities searched the land- MgCf filled the National Mall fill for the body of a newborn and the streets of Washington. until late Thursday. D.C , on Saturday to protest the War in Ir.itj and President Hush's proposed troop BUfgS Protest organizers Lnited For Peace and justice estimated Authorities 500.00M took part In the dem- onstration. Among those were .1 number of JML students. call oil I v. .is blown away h\ how m my people from JMU came," sophomore Marlev Creen said baby search "I know of ,it least 35-plllS peo- ple who went, and everyone •v MAJTI FRANCIS OARS n I met had I great time [here itvusbmt WHS editor could always be more, though Said sophomore Nick Milas: EVAN DYSON/ph-io e&or HARRISONBURG — Officials TheM events are what make at the Rockingham County Sheriff's history Nothing feels createi A man was found outside Kyger Funeral Home with a gunshot wound Monday afternoon at approximately 1 p.m. Office have called off the search for lhan to he with a shocking!; the bodv ol ,\n infant said to have large group ol people |iist to been left in a dumpster late Iliurv show Premier Bush where we day night. -

Anagencyyou Shouldknow

61041pg001-004.QXD 9/11/06 2:05 PM Page 1 November 2006 Vol. 22, No. 11 A newsletter just for you! AnAgencyYo u ShouldKnow: Occasionally, the Pen Pal will highlight a non-profit agency whose efforts have Kids Hope United benefited our community. If you know of such an agency, please let us know! As a child, Crystal Price, 26, witnessed her alcoholic father abuse her The majority of KHU cases are referred by juvenile courts or state mother. Unfortunately, as happens with many children exposed to this type agencies. However, the agency also offers Head Start, an early childhood and of behavior, she had repeated the pattern. While raising four children, she after school program. was involved with drugs and endured domestic abuse from her long-time “It’s not just about those who are abused and neglected, but our boyfriend. When her boyfriend was sent to jail, the Department of Children programs keep [kids] from becoming abused and neglected,” said KHU and Family Services got involved, along with Kids Hope United (KHU), to president and CEO, Martin Sinnott. “We help support kids and those at help Crystal secure the resources she needed to get back on her feet. greatest risk. What we are really about is keeping families together, reuniting Price and her children were among the approximate 2.9 million kids with families when they’ve been removed, and creating forever families referrals received annually involving abuse and neglect of minor children. when families are not capable of the first two.” KHU is a private, human service organization based in Chicago that serves “The child welfare system here is broken,” added Sinnott. -

NATIONAL CONFERENCE April 12 -15 , 2017

NATIONAL CONFERENCE April 12th-15th, 2017 Marriott Marquis Marina San Diego, CA Jennifer Loeb PCA/ACA Conference Coordinator Joseph H. Hancock, II PCA/ACA Executive Director of Events Drexel University Brendan Riley PCA/ACA Executive Director of Operations Columbia College Chicago Sandhiya John Editor Wiley-Blackwell Copyright 2017, PCA/ACA Additional information about the PCA/ACA available at pcaaca.org Table of Contents President’s Welcome 2 Conference Administration 3 Area Chairs 3 Officers 15 Board Members 15 Program Schedule Overview 18 Special Events & Ceremonies 18 Exhibits & Paper Table 20 2017 Ray and Pat Browne Award Winners 22 Special Guests 23 Schedule by Topic Area 24 Daily Schedule Overview 69 Full Daily Schedule 105 Index 244 Floor Maps 292 Dear PCA/ACA Conference Attendees, Welcome! We are so pleased that you have joined us in San Diego for what promises to be another stimulating and enriching conference. In addition to the hundreds of sessions available, a meeting highlight will be an address from our Lynn Bartholome Eminent Scholar awardee, David Feldman of Imponderables fame. As always, there will be plenty of times and spaces to connect with old friends and make new ones: area interest sessions, coffee breaks, film screenings, and special themed events and roundtables. Be sure to take advantage of the networking and scholarly connection opportunities in the book exhibit room. And don’t forget about Friday’s all conference reception! Graduate students and new-comers, we welcome you especially. We hope you will find this a professional home for years to come. Finally, as you depart San Diego at week’s end, be sure to mark your calendars for our Indianapolis meeting, March 25 – April 1, 2018. -

Board Game Project (Due December 15Th) You and Your Partner(S) Will Be Designing Your Own Board Game

Board Game Project (Due December 15th) You and your partner(s) will be designing your own board game. Remember all those great games you have played? Well, now you can make your own; your own rules, your own design, your own questions! The only thing is, you must relate it to Doll Bones. First, before you start thinking about your “new” design, think about board games that you like to play, or ones that you have played before--- Board Game List o Apples to Apples o Clue o Life on the Farm o Scrabble o Are You Smarter o Cooties o Mall Madness o Sorry! Than a 5th o Cranium o Monopoly o Taboo Grader o Don't Wake o Mouse Trap o Trivial Pursuit o Boggle Daddy o Obsession o Trouble o Candy Land o Guess Who? o Operation o Yahtzee o Checkers o Hi Ho! Cherry-O o Payday o _____________ o Chess o Hungry Hungry o Pictionary o _____________ o Chutes and Hippos o Rummikub o _____________ Ladders o Life o Scene It Now, it’s your turn to create a board game based on Doll Bones by Holly Black. REMEMBER board games should be fun, interactive, and structured. Use your creative minds to think of ways to relate the people, places, and events in Doll Bones to creating a board game. Requirements: Each board game made must have the following items included in the project Actual playing board: including game pieces and any necessary devices to complete your designed game Game theme, questions, statements, layout, design must be related to Doll Bones.