K E Y N O T E Louis Riel: Patriot Rebel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resources Pertaining to First Nations, Inuit, and Metis. Fifth Edition. INSTITUTION Manitoba Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 400 143 RC 020 735 AUTHOR Bagworth, Ruth, Comp. TITLE Native Peoples: Resources Pertaining to First Nations, Inuit, and Metis. Fifth Edition. INSTITUTION Manitoba Dept. of Education and Training, Winnipeg. REPORT NO ISBN-0-7711-1305-6 PUB DATE 95 NOTE 261p.; Supersedes fourth edition, ED 350 116. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indian Culture; American Indian Education; American Indian History; American Indian Languages; American Indian Literature; American Indian Studies; Annotated Bibliographies; Audiovisual Aids; *Canada Natives; Elementary Secondary Education; *Eskimos; Foreign Countries; Instructional Material Evaluation; *Instructional Materials; *Library Collections; *Metis (People); *Resource Materials; Tribes IDENTIFIERS *Canada; Native Americans ABSTRACT This bibliography lists materials on Native peoples available through the library at the Manitoba Department of Education and Training (Canada). All materials are loanable except the periodicals collection, which is available for in-house use only. Materials are categorized under the headings of First Nations, Inuit, and Metis and include both print and audiovisual resources. Print materials include books, research studies, essays, theses, bibliographies, and journals; audiovisual materials include kits, pictures, jackdaws, phonodiscs, phonotapes, compact discs, videorecordings, and films. The approximately 2,000 listings include author, title, publisher, a brief description, library -

LOUIS RIEL, from HERETIC to HERO: a NEW HISTORICAL SYNTHESIS by Wesley Brent Bilsky a THESIS SUBMITTED in PARTIAL FULFILLMENT O

LOUIS RIEL, FROM HERETIC TO HERO: A NEW HISTORICAL SYNTHESIS By Wesley Brent Bilsky A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS Supervisor: Gregg Finley, PhD Second Reader: Aloysius Balawyder, PhD Copy Editor: Judith L. Davids, M.C.S. This Thesis Is Accepted By: _____________________________ Academic Dean ST. STEPHEN’S UNIVERSITY April 16, 2011 Bilsky CONTENTS ABSTRACT ………………………………………………………………………………………...…......... i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ………………………………………………………………………..…….... iii PREFACE ……………………………………………………………………………………………....…. iv INTRODUCTION: ALMOST A HERO ………………………………………………………………….... 1 CHAPTER I HISTORICAL REVISIONISM: PURPOSE VERSUS PERCEPTION ….….…………..…... 6 Purpose ……………………………….………………………………………………………………... 6 Perception ……………………………….…………………………………………….……………… 12 Closing the Gap ……………………………….……………………………………...................….… 15 The Historical Window ……………………….……………………………………………………… 18 CHAPTER II REVISING RIEL: FROM REBEL TO MARTYR …………………………..…………..... 21 A Rebel is Born ………………………………………………………….…………………………… 21 A Captivity Narrative ………………………………………………………….……………………... 26 Early Influences ………………………………………………………….………................................ 28 The Metamorphosis Begins – 1869 ……………………………………………………….…….……. 30 Building on Stanley and Morton ………………………………………………….………………….. 36 The Birth of a Martyr – 1885 ………………………………………………….……………...….…... 40 The Charges Challenged …………………………………………………........................................... 46 A Collaborative Future ……………………………………………………………………...…….…. 49 -

Métis Resources Available Through the Aboriginal Nations Education Library Greater Victoria School Board Office 556 Boleskine Road, Victoria, Bc V8z 1E8

MÉTIS RESOURCES AVAILABLE THROUGH THE ABORIGINAL NATIONS EDUCATION LIBRARY GREATER VICTORIA SCHOOL BOARD OFFICE 556 BOLESKINE ROAD, VICTORIA, BC V8Z 1E8 Secondary: A Very Small Rebellion Fifty Historical Vignettes (Views of the Common 813.54: TRU People) Jan Truss 971.2: McL Novel Don Mclean A historical overview of the Métis people. Back to Batoche 813.6: CHA First Métis, The: A New Nation Cheryl Chad 971: AND The discovery of a magic pocket watch send three Dr. Anne Anderson children back into time to the Battle of Batoche. A historical overview of the Métis Nation. Buffalo Hunt, The Growth of the First Métis Nation 971: GAB 371.3: FNED Teacher’s Curriculum Guide & Lesson Plans Ekosi Available Through Aboriginal Nations Education 811.6: ACC Division, SD #61 Anne Acco A Métis retrospective of poetry and prose. Home from the Hill: A History of the Métis In Western Canada Expressing Our Heritage: Metis Artistic Designs 971.2: McL 391.008: TRO Don McLean Cheryl Troupe Métis arts including language and glossary. Honour the Sun (Grades 7 to 12) PI 813.54: SLI Gabriel Dumont Institute/Pelletier Ruby Slipperjack Cries from a Métis Heart After years away, a young woman returns to the 971.004971: MAY railroad community in northern Ontario where she Lorraine Mayer was raised, only to find life there has turned for the From the ghosts of her past, the author struggles as worse. As trouble reaches her mother and her a mother, an academic and a Métis woman to find friends, will she, too, succumb to despair? her identity and freedom. -

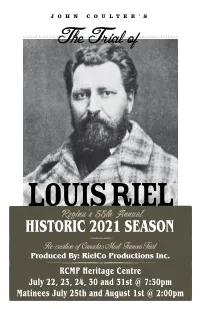

View 2021 Performance Program of the Trial of Louis Riel

Trial of Louis riel Pstr July 17 Press Ready.pdf 1 2017-07-18 2:05 PM Trial of Louis Riel Pgm Cvr July 17 Press Ready.pdf 1 2017-07-18 10:22 AM JOHN COULTER’S JOHN COULTER’S TheThe TrialTrial ofof C M Y CM C M MY Y CM CY MY CY CMY CMY K K LOUISLOUIS RIELRIEL 50th50th AnniversaryAnniversary ReunionReunion CelebrationCelebration HISTORICHISTORICHISTORIC 2021 2017 SeasonSeasonSEASON Re-creation of Canada’s Most Famous Trial ProducedProducedRe-creation By: of Canada’s RielCo Most Productions Famous Trial Inc. Inc. Produced By: RielCo Productions Inc. SUMMERSUMMERRCMP PERFORMANCES Heritage PERFORMANCE Centre ~ 7:30 P.M. July July22, 20th,23, 24,21st, 30 22nd, and 27th, 31st 28th, @ 29th7:30pm Matinees July 25thAugust and 3rd, August 4th, 5th 1st @ 2:00pm royal saskatchewan museum, REGINA, SK - 2445 Albert Street Tickets www.rielcoproductions.com Tickets at Or the at the door Royal Saskatchewan or museum kiosk https://rcmphc.com/en/trial-of-louis-riel-productionTickets also available at the door FOR MOREFor more INFORMATION information: CALL 1-306-728-5728 306-522-7333 Welcome to the Trial of Louis Riel Production The RCMP Heritage Centre is proud to partner with RielCo Productions to host The Trial of Louis Riel production on its 55th anniversary this summer. The play – a re-enactment of one of Canada’s most famous trials – is the longest continuously-running historical drama in North America. Written as a Centennial project in 1967 by John Coulter, the production is based on the actual court transcripts of the 1885 trial of Louis Riel in Regina. -

Louis Riel (1844-1885): Biography

Louis Riel (1844-1885): Biography Louis Riel, Métis leader and martyr, was born in St. Boniface, Red River Settlement (later Winnipeg, Manitoba) on October 22, 1844 to Jean- Louis Riel and Julie Lagimodière. He was the oldest of eleven children. In March 1882, he married Marguerite Monet dit Bellehumeur in Carrol, Montana Territory. The couple had two children: Jean (May 1882) and Angèlique (September 1883). After arguably the most politically explosive trial in Canadian history, he was executed for High Treason on November 16, 1885. Louis Riel led the Métis in two resistances during 1869-70 in Red River and in 1885 in the Saskatchewan District of the North-West Territories (present-day central Saskatchewan). Riel had leadership in his blood: his father Jean-Louis organized Métis hunters and traders to bring an end to the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC)’s fur trading monopoly. Guillaume Sayer and three other Métis had been charged with illegal trading. However, on May 17, 1849, the day of their trial, the senior Riel organized an armed group of Métis outside of the courthouse. While the traders were found guilty, the Métis were so intimidating that the HBC Magistrate who presided over the trial let Guillaume and the others go without imposing a fine. This event virtually ended the HBC’s monopoly trading monopoly in what is now Western Canada. Louis Riel did not at first want a life in politics. When he was fourteen, priests sent him and other intelligent Métis boys to Canada East (now Québec) to attend the collège de Montréal. -

Non Compos Mentis: a Meta-Historical Survey of the Historiographic Narratives of Louis Riel's "Insanity" Gregory Betts

Document generated on 10/02/2021 1:11 a.m. International Journal of Canadian Studies Revue internationale d’études canadiennes Non Compos Mentis: A Meta-Historical Survey of the Historiographic Narratives of Louis Riel's "Insanity" Gregory Betts Borders, Migrations and Managing Diversity: New Mappings Article abstract Frontières, migrations et gestion de la diversité : nouvelles In light of charges of High Treason, Louis Riel's Defence Counsel pleaded non cartographies compos mentis, not guilty by reason of insanity. The prisoner disagreed with Number 38, 2008 his counsel and protested his sanity three times during the trial. With his own lawyers discrediting the validity of his political and religious ambitions, Riel URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/040805ar was unsatisfied with his counsel. Similarly, critics, activists, and nationalists DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/040805ar also have had an awkward time effectively responding to the question of Riel's insanity. This paper considers the uses of Riel's insanity defense, in particular the opinions of the various psychologists whose judgments determined Riel's See table of contents fate, his trial, and many of the posthumous responses. Publisher(s) Conseil international d'études canadiennes ISSN 1180-3991 (print) 1923-5291 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Betts, G. (2008). Non Compos Mentis: A Meta-Historical Survey of the Historiographic Narratives of Louis Riel's "Insanity". International Journal of Canadian Studies / Revue internationale d’études canadiennes, (38), 15–40. https://doi.org/10.7202/040805ar Tous droits réservés © Conseil international d'études canadiennes, 2008 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. -

Individual Report for Edward George Paul Edwin Jackson Brooks Individual Summary: Edward George Paul Edwin Jackson Brooks 09 Dec 1848 - 1939

Individual Report for Edward George Paul Edwin Jackson Brooks Individual Summary: Edward George Paul Edwin Jackson Brooks 09 Dec 1848 - 1939 Sex: Male Father: Charles Brooks Mother: Sally Abbott Individual Facts: Baptism: 1848 in Sherbrooke, Québec Birth: 09 Dec 1848 in Lennoxville, Quebec Census: 1881 in Census indicates occupation as clerk Census: 1881 in Census indicates religion as Congregational Moved To Indian Head: 1882 Residence: 1901 in Indian Head, Assiniboia (east/est), The Territories, Canada Vital: 1901 in Qu'Appelle, Northwest Territories Residence: 1906 in Town of Indian Head, Qu'Appelle, Saskatchewan, Canada Residence: 1916 in 17, Indian Head, Qu'Appelle, Saskatchewan, Canada Death: 1939 Burial: Indian Head, Saskatchewan Shared Facts: Helena Ermina Oughtred Marriage: 14 Mar 1876 in Lennoxville, Quebec Children: Charles Brooks Harry Brooks Allan Scott Brooks Edwin Brooks Murray Gordon Brooks Bessie Brooks Ernest Brooks Arthur Brooks Mary Brooks Frank Brooks Sarah Brooks Notes: Person Notes: Juror at the trial of Louis Riel, Regina, 1885. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -------------------------------------------------------------------- Riel: A Life Of Revolution, Maggie Siggins, Harper Collins Publishers Ltd., Toronto, 1994. "Among the panel of thirty-five possible jurors, two had French names; neither was chosen to sit. All six jurors selected - Francis Cosgrove, the chairman, Walter Merryfield, Henry J. Painter, Edwin J. Brooks, Bell Deane and Ed Everet - were Anglo-Saxon Protestants. Only Brooks, who had been born in Quebec, could speak French." "Juror Edwin Brooks, a merchant from Indian Head, scribbled down notes during the trial, including a description of Riel: A good-looking man, fair complexion, high forehead, wavy black hair, of medium height, full beard, like John the Baptist, sharp flashy eyes, small sensitive hands that twitch all the time and which he uses a great deal in talking, waving them around like the arms of a windmill. -

Article the Métis-Ization of Canada: the Process of Claiming Louis Riel, Métissage, and the Métis People As Canada’S Mythical Origin Adam Gaudry Ph.D

Article The Métis-ization of Canada: The Process of Claiming Louis Riel, Métissage, and the Métis People as Canada’s Mythical Origin Adam Gaudry Ph.D. Candidate, Indigenous Governance, University of Victoria; 2012–2013 Henry Roe Cloud Fellow, Yale University aboriginal policy studies Vol. 2, no. 2, 2013, pp. 64-87 This article can be found at: http://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/aps/article/view/17889 ISSN: 1923-3299 Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5663/aps.v2i2.17889 aboriginal policy studies is an online, peer-reviewed and multidisciplinary journal that publishes origi- nal, scholarly, and policy-relevant research on issues relevant to Métis, non-status Indians and urban Aboriginal people in Canada. For more information, please contact us at [email protected] or visit our website at www.ualberta.ca/nativestudies/aps/. The Métis-ization of Canada: The Process of Claiming Louis Riel, Métissage, and the Métis People as Canada’s Mythical Origin1 Adam Gaudry Ph.D. Candidate, Indigenous Governance, University of Victoria; 2012–2013 Henry Roe Cloud Fellow, Yale University Abstract: The historical narrative around Métis political leader Louis Riel has undergone a extraordinary change since the 1960s—once reviled by Anglo-Canadians, Riel is now paradoxically celebrated as a Canadian hero, and this “Riel-as-Canadian” narrative has become a common trope in contemporary Canadian political culture. Emanating from the Canadianization of Louis Riel is a parallel colonial discourse that distances itself from past attempts to assimilate Indigenous people into Canada, arguing instead for the assimilation of Canadians into a pan-Indigenous political identity. -

Teacher's Guide

(1869 – 1870) Teacher’s Guide 2015 Copyright © 2015 by Louis Riel Institute 103-150 Henry Ave Winnipeg, Manitoba R3B 0J7 All Rights Reserved ISBN 978-1-927531-09-9 Every effort has been made to acknowledge original sources and to comply with copyright law. If cases are identified where this has not been done, please notify Louis Riel Institute. Errors or omissions will be corrected in a future edition. Acknowledgements Advisory Committee Members • Grant Anderson, Policy Analyst, Manitoba Aboriginal and Northern Affairs • Lawrie Barkwell, Coordinator of Metis Heritage and History Research, Louis Riel Institute • Linda Connor, Consultant, Manitoba Education and Advanced Learning • Shirley Delorme Russell, Curriculum Development Specialist, Louis Riel Institute • Renée Gillis, Conseillère pédagogique en sciences humaines, Bureau de l’éducation française • Jeff Legault, Policy Analyst, Manitoba Aboriginal and Northern Affairs • Georgina Liberty, Director, Manitoba Metis Federation Tripartite Self Government Negotiations • Sharon Parenteau, General Manager of the Louis Riel Institute • Greg Pruden, Consultant, Aboriginal Perspectives, Manitoba Education and Advanced Learning • Alison Rogan, Manager, Policy and and Strategic Initiatives, Manitoba Aboriginal and Northern Affairs Table of Contents About This Teacher’s Guide . 1 What is the Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia (LAA)?. 3 History of Red River & Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia. 6 Manitoba Curriculum Links ........................................ 10 Other Curriculum Links ............................................11 Suggested Questions for Class Discussion . 12 Part 1: Introduction ............................................... 13 1.1: Backpack / St. Boniface Museum / Hudson Bay Company Archives ......13 1.2: The Métis (Yesterday & Today). 14 1.3: Placemats Jigsaw. 17 1.4: Google Earth and the History of Red River by Streets .................19 Part 2: Welcome McDougall or Stop Him? ............................ -

The Trial of Louis Riel After an Absence of 37 Years

Trial of Louis riel Pstr July 17 Press Ready.pdf 1 2017-07-18 2:05 PM JOHN COULTER’S The Trial of Trial of Louis riel Pstr July 17 Press Ready.pdf 1 2017-07-18 2:05 PM Trial of Louis Riel Pgm Cvr July 17 Press Ready.pdf 1 2017-07-18 10:22 AM JOHN COULTER’S JOHN COULTER’S TheThe TrialTrial of of C M Y CM MY CY C CMY M K Y CM C M MY Y CM CY MY CY CMY CMY K K LOUIS RIEL 50th Anniversary Reunion Celebration HISTORICLOUISLOUIS 2017 RIEL RIEL Season 50th50th AnniversaryAnniversaryRegina's Reunion51st Reunion An Celebration n Celebration u a l HISTORICReHISTORIC-creation of Canada’s 20182017 Most SeasonSEASON Famous Trial ProducedHISTORIC By: RielCo 2017 Productions Season Inc. ReRe-creation-creation of of Canada’s Canada’s MostMost Famous Trial Trial ProducedRe-creation By: of Canada’s RielCo Most Productions Famous Trial Inc. SUMMERProducedProduced PERFORMANCES By:By: RielCo RielCo Productions Productions ~ Inc. Inc.7:30 P.M. SUMMERSUMMER PERFORMANCESPERFORMANCES ~ ~ 7:307:30 P.M.P.M. July 20th,SUMMER 21st, PERFORMANCE 22nd, 27th, 28th, 29th JulyJuly 19th20th,August - 21st, August 22nd, 3rd, 4th 27th,on 4th, Thurs/Fri/Sat 28th, 5th 29th August 3rd, 4th, 5th royal saskatchewan museum, REGINA, SK - 2445 Albert Street royal saskatchewan museum, REGINA, SK - 2445 Albert Street TicketsTickets www.rielcoproductions.com www.rielcoproductions.com Or Or at the at theRoyal Royal Saskatchewan Saskatchewan museum kiosk museum kiosk TicketsTickets alsoalso available available at the at door the door For more information: 1-306-728-5728 For more information: 1-306-728-5728 CAST MEMBERS Louis Riel....Nicholas Boudreau (First Two Weeks) John D. -

Newsworld, Riel, and the Métis: Recognition and the Limits to Reconciliation

Newsworld, Riel, and the Métis: Recognition and the Limits to Reconciliation Maurice Charland Concordia University Abstract: This article examines the rhetorical character of CBC Newsworld’s 2003 “re-trial” of Métis leader Louis Riel. Specifically, it considers how the broadcast was presented as a gesture of reconciliation toward the Métis but was received by Métis spokespersons as racist or colonizing. The broadcast is analyzed through Robert Hariman’s conception of the popular trial as an occasion for the develop- ment of argumentative resources to deliberate on problematic issues within public culture. The broadcast and its reception are then analyzed critically to highlight the tensions between identity, recognition, and reconciliation. Résumé: Cet essai cerne les enjeux rhétoriques de la mise en scène en 2003 d’un nouveau procès juridique de Louis Riel par CBC Newsworld. Il fait état du fait que ce procès fut conçu comme un geste de réconciliation mais fut interprété par les porte-parole des métis comme raciste ou colonisant. Selon cette analyse, l’émis- sion contribue à une rhétorique de « procès populaire » qui, selon Robert Hariman, offre des ressources argumentatives pour délibérer les controverses sociocul- turelles. Par la suite, le programme et sa réception font l’objet d’une discussion cri- tique portant sur les tensions entre l’identité, la reconnaissance et la réconciliation. Keywords: Rhetoric; Public Address; Popular Trials; Reconciliation; Recognition; Identity; Law; Postcolonialism; Métis; Louis Riel On October 22, 2003, Newsworld, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s all- news channel, revisited the case of Louis Riel, who was executed for high treason over a century ago. -

Louis Riel, Justice, and Mtis Self-Identification: Literary Politics

Robin White Goldsmiths College, University of London Thesis for the Degree of Ph.D., 2014 Louis Riel, Justice, and Métis Self-Identification: Literary Politics for Survival in the Evolution of Canadian Nationhood 1 I, Robin White, declare this thesis to be entirely my own original work. 2 Abstract of Thesis This thesis explores Métis identity in the context of the ambiguous nature of the Canadian national identity, and in particular, how the Louis Riel ‘Rebellions’ of 1869- 70 and 1885, continue to resonate in contemporary Métis literature. While it is the case that the Métis have self-identified within their own communities since the seventeenth century, it is also the case that the legal definition and recognition of the Métis were not realized until 1982. Indeed, the fine points of law in the Canadian Constitution are still in dispute, not least because the Métis were not included in the initial signing of treaties with the Dominion of Canada. For the purposes of this thesis, it is first necessary to engage in a thorough examination of historical accounts of the resistance of the Métis against expansionist encroachment of the Dominion of Canada in the Northwest in order to trace the source and evolution of contemporary Métis literature. I consider the ways in which the literary texts of Métis authors confront racial and cultural prejudice that are the direct result of Constitutional law, charters of rights, legislation in the judicial system, and the eleven Confederation numbered treaties, drafted before, during and after the Riel Resistances. The introductory and first chapters include contemporary Métis historical and legal academic analyses of the ‘Rebellions’ and an exploration of how the Government of Canada’s response in 1885 to the Métis uprising continues to inform its legal positions concerning Métis land rights and self-identification, while striving to maintain an international reputation as politically, and ethically, just.