Truck and Bus Tires from China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KASH UTTAM Brute Boxcoolers Hot Products/Page64 Bespoke Tires Specifically Designed and Produced for You

TP www.tiresandparts.net l DHS 20 /- USD 5.99/- JULY /AUGUST 2014 /AUGUST JULY The Middle East’s First Automotive, Tires & Parts News Source ISSUE 94 l LIMITED EDITION TRUE BLUE ROLLS-ROYCE WATERSPEED COLLECTION DEBUTS IN UAE MARKET Hot Products / Page 64 KASH UTTAM Brute Box Coolers MANAGING DIRECTOR OF SGTC www.alexiatires.com Bespoke tires Specifically designed and produced for you. ART 1100 ART 1200 ART 1300 ART 1400 ART 1500 ART 1600 ART 1700 ART 1900 Guided by the main principles of value, trust, honesty and quality Alexia tires has been proudly manufacturing commercial and OTR tires from Asia with the intention to fill a gap in the replacement tire market. Alexia Tires believes in delivering the greatest value, quality and service without com- promising on innovation and style. With over 35 years of experience in the industry, Alexia Tires is passionate about its work. We bring to the market unique tire products and designs that specialize in the manufacturing of custom products that fit the market requirements of the day. Alexia’s strength lies in its flexibility and its ability to listen to the demands of the market and make subsequent swift changes as needed. Alexia Tires is a global company comprised of passionate designers and engineers who continue to use the latest technology to deliver the most innovative and original tires in the market. With worldwide distribution, Alexia Tires looks forward to further reaching out to the masses with truly one of a kind products and continuing to be trailblazers in the industry. For exclusive territory enquiries pls contact [email protected]. -

Member List by Country

Member List A-Z Categories 28 September 2021 r = Retreader s = Supplier td = Tire Dealer c = Casing Dealer m = Tire & Trucking Magazine I = Individual o = Other ntm = New Tire Manufacturer a = Association tc = Trucking Company rc = recycling trm = tread rubber manufacturer trp = tire repair company Category Member Name City State/Province Country Telephone Website trp 31 Incorporated Newcomerstown OH USA 740-498-8324 X105 for Bob 31inc.com r Action Tire Company Forest Park GA USA 404-767-3235 actiontireco.com Advantage ID / Symbology, s Maple Grove MN USA 763-315-8080 advantageid.com Inc. s Advantage PressurePro LLC Harrisonville MO USA 816-887-3505 advantagepressurepro.com td Aero Tires Company Miami FL USA 305-885-2411 www.aerotiresco.com trm Air Boss Kitchener ON CANADA 1-800-294-5723 airbossofamerica.com AKAR MAKINA SANAYI s Eskisehir TURKEY 90-222-2361700 akarmak.com.tr LTD Akron Rubber Development o Akron OH USA 330-794-6600 ardl.com Laboratory, Inc. ntm Alliance Tire Americas, Inc. Wakefield MA USA 781-321-3910 atgtire.com r Allied Retread Technologies Omaha NE USA 800-333-3717 allied-oil.com s AME International Brooksville FL USA 352-799-1111 ameintl.net Zona Industrial DOMINICAN r AMV Dominicana Santo Domingo 809-333-7774 amvdominicana.com Manoquayabo REPUBLIC r Anderson Tire & Co. Ltd. Hamilton AB CANADA 905-560-7721, 888-727-2411 r Ardmore Tire Conshohocken PA USA 610-834-1075 Asociacin de Renovadores a y Recauchadores de Santiago CHILE arnec.cl Neumticos de Chile s ATEC, Inc. Phoenix AZ USA 602-253-3921 r Auto & Truck Tyres (Pty) Ltd. -

Global Tire Intelligence Report

Return to Contents page Global Tire Intelligence report RESEARCH Dateline: 31 July 2016 Compiled by Shaw Information Services trading as Contents Bridgestone makes Senior Management Changes 7 Tire Industry Research Goodyear Reports Q2, H1 Results 7 © 2016 Shaw Information Services Ltd Section 1: Outlook 2 Michelin marks 70 years since inventing the Radial 7 President Trump would encourage trade barriers 2 Continental supplies tires for Volvo Concept 7 Yokohama uses Exa’s aerodynamic model 7 For subscription enquiries Survey reveals extent of illegal truck tires on US roads 2 Will US government legislate on tire grip? 2 Michelin reports higher profit and volumes in first half 8 [email protected] Conti names new Head of Commercial Specialty Tires 8 +44 208 647 1185 IRSG forecasts lower NR growth 2 Bridgestone’s vision of the future 2 Yokohama completes acquisition of Alliance Tire 8 EC truck producers fined €2.93 billion for cartel 3 Kumho tire share for sale 8 Cheng Shin chairman talks Maxxis globalisation 8 About this publication 2 Kenda Tire discusses Tech centre in North America 9 Section 2: Sustainability 4 Section 6: Upstream and raw materials 9 Michelin commits to zero deforestation 4 Asahi Kasei, JSR adding S-SBR materials 9 Toyo Tires Supports SNR-i 4 Evonik opens competence centre for silanes 9 3D printing using rubber from end-of-life tires 4 Evonik opens silica plant in Brazil 9 Irish Minister ends voluntary waste tire reporting 4 Malaysia’s NR production falls 9 Recycled tires can improve soil drainage 4 NR prices -

Pattern Digest 2020 Passenger Car, SUV/4X4, and Light Truck Tires Explore the World with Giti Tire

Pattern Digest 2020 Passenger Car, SUV/4x4, and Light Truck Tires Explore the World with Giti Tire You are intrinsically passionate and always stay curious. You have no fear for challenge and you enjoy exploration. You have never stopped pursuing your dreams. And on the journey in pursuit of dreams, you always persist through challenges. You always insist on being true to yourself Hit the Road. Witness affection, encounter miracles, embrace the extraordinary, taste ecstacy. Be your own explorer. Explore yourself. Explore with Giti. Table Of Contents Introduction -A Global Tire Company 1 -Manufacturing and R&D 6 -OEM Partnerships & Awards 8 -Giti Motorsports Tires 10 -Tire Mapping 11 Product Range - 16 - 19 - 25 - 29 - 32 -Tire Knowledge 33 -OEM Partners 36 A Singapore Based Global Tire Company Giti Tire has been in the tire business for more than 60 years. The company has become one of the world’s largest tire manufacturers, serving customers in more than 130 countries. 2018 Revenue USD 3.2 Billion R&D and Testing Centers 5 4 R&D in Germany, USA, China, Indonesia, and 1 testing center in UK Manufacturing Plants 8 6 in China, 1 in Indonesia 1 Newly opened in the US Offices 12 Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, China, U.S., Canada, U.K., Germany, France, Brazil, Italy and Dubai More than Employees 35,000 Worldwide More than Points of Sale 70,000 In more than 130 countries 55 Green and Global Manufacturing in Three Countries Giti Tire’s newly opened US manufacturing center joins the companies’ other factories in China and Indonesia. -

2012 Exhibitors List

2012 Exhibitors List Company Country Pavilion Products Brands 8 You 8 E-Commerce GmbH Germany A & B Films Pte Ltd Singapore Singapore Pavilion Screen coatings, Tinted window foils Solar Master Window Films A.K.S Taiwan Taiwan Pavilion A.M.C. Motor (Amornchai) Co., Ltd. Thailand Thai Pavilion AAPE Media Technology Co., Ltd. Taiwan Taiwan Pavilion Abdul Zahir Bashir General Trading LLC United Arab Emirates Tyres, Batteries A-Belt-Lin Industrial Co., Ltd. Taiwan Taiwan Pavilion Abhirashi Impex India Indian Pavilion Automotive Heavy Duty Gauges, Senders, Cluster Assemblies Aboras Auto Spare Parts Trading LLC United Arab Emirates Tyres, Batteries Aborn Auto Parts Mfg.(China)Co.,Ltd. China China Pavilion Sensor, Voltage Regulator, Controller, Relay, Step Motor, Resistor, Ignition Module Accor Lubrifiants France French Pavilion ACF Industrials Co., Ltd. Taiwan Taiwan Pavilion Achieve Made ME FZE (DATO) United Arab Emirates Garage tools DATO Achieve Made ME FZE (Launch) United Arab Emirates Garage Equipments, Lift Equipments LAUNCH ACL Automotive Components United States Acme Udhyog India Indian Pavilion Auto & Tractor parts Acr(China) Inc China China Pavilion Engine Mounting, Torque Rod Bushing, Shock Absorber ACT Aerosol Chemie Technik GmbH Germany German Pavilion Motor Oil Actia Muller France French Pavilion Adel Bou Habib & Partners Lebanon Oils & Lubricants Petrol Ofisi ADR Group of Companies Indonesia Filter, Radiater Sakura, ADR Advanced Expedition Vehicles Trading LLC (AEV) United Arab Emirates Acessories & Tuning Bushwacker, Corsa, Gibson Aeolus Tyre Co.,Ltd. China China Pavilion Tyres AEOLUS, WINDPOWER, HENAN Aeroklas Co., Ltd. Thailand Bed liners, Tonneau cover Aeroklas Affinia Group Inc. United Arab Emirates Brake systems, Steering components, Suspension components Afrivision Tunisia Tunisian Pavilion Air Fren S.L. -

2019-Giti Corporate

uilding & Support • B Better Commu Service nities us on Foc • A ports tors Mo bal Glo ium rem n P t i en m ve ol nv • I g in tur c fa u n a M n e re G d n a al b o Gl Company & Brand Overview A B A Singapore Based Global Tire Company C E D A: Taking on the 24 Hours Nürburgring Race B: Giti Booth at CV Show in Europe C: Inside Giti Tire's newest plant in Chester, South Carolina, USA D: Display for the 'More sMiles with Giti' branding campaign E: Giti Tire's German Office Giti Tire has been in the tire business for more than 65 years. The company has become one of the world’s largest tire manufacturers, serving customers in more than 130 countries. 2018 Revenue USD 3.2 Billion R&D and Testing Centers 5 4 R&D in Germany, USA, China, Indonesia, and 1 testing center in UK Manufacturing Plants 8 6 in China, 1 in Indonesia 1 in the US Offices 12 Singapore, China, Indonesia, U.S., Canada, U.K., Germany, France, Dubai, Malaysia, Italy, and Brazil More than Employees 35,000 Worldwide More than Points of Sale 70,000 In more than 130 countries 1 Recent Highlighted Growth and Developments 01 03 Expanded Global and State of the Art New Tires Green Manufacturing The fully integrated Global One Gradual ramping up of the R&D technology platform enables new US factory and expanding Giti engineers operating across Indonesian production center has North America, Europe, China, and increased Giti's overall capacity, Indonesia to provide our everyday with a continuous focus on drivers with better, safer and more automation for higher productivity durable state of the art tires. -

Will Duties Cause Shortage of TBR Tires?

www.tirebusiness.com April 15, 2019 $79 per year, $4 per copy Tire Business Special Report CommercialTire& Will duties cause shortage of TBR tires? RetreadingReport Mergers/acquisitions high- USTMA forecasts medium-duty product shipments to drop in 2019 10 light 2018/19 commercial By Bruce Davis medium-duty truck/bus shipments this year. those tariffs, the moves proved providential when sector developments [email protected] The drop, which translates to 1.5 million units, the Department of Commerce handed down in ill the newly imposed countervailing is tied primarily to the anticipated impact of the February its decision to impose countervailing North America’s and antidumping import duty orders on higher import duties on China, the No. 1 source of and antidumping duty orders on truck and bus 14-15 largest commercial Wtruck and bus tires from China lead to imported truck tires. tires from China, sources said. dealerships chart shortages of tires and/or rising prices? Truck tire imports from China last year soared The surplus inventory of these “tariff-beater” That scenario seems to be more than likely, ac- 42.1 percent to 9.22 million units, or more than half imports on hand could serve to ll the gap, at least Bridgestone launches ‘Fleets cording to various sources contacted by Tire Busi- of all imports. The increase, however, was in ated temporarily, for any shortfalls in new imports, 17 We Depend On’ retreading ness. The big question, however, is: To what extent? by importers’ placing extra orders toward year-end sources indicated. education campaign The U.S. -

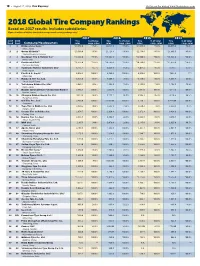

2018 Global Tire Company Rankings Based on 2017 Results

18 • August 27, 2018, TIRE BUSINESS Visit us on the web at www.tirebusiness.com 2018 Global Tire Company Rankings Based on 2017 results. Includes subsidiaries. (Figures in millions of dollars, translated at average annual currency exchange rates) 2017 2016 2015 2014 2017 2016 Tire % of total Tire % of total Tire % of total Tire % of total Rank Rank Company/Headquarters sales corp. sales sales corp. sales sales corp. sales sales corp. sales 1 1 Bridgestone Corp.# 1 *24,350.0 *75.0% 22,121.0 *75.0% *24,045.0 *75.0% *26,045.0 *75.0% Tokyo, Japan 2 2 Group Michelin#2 *23,560.0 *95.0% 21,129.4 *95.0% *22,130.0 *95.0% *24,668.5 *95.0% Clermont-Ferrand, France 3 3 Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.# *14,300.0 *93.0% *13,645.0 *90.0% *14,800.0 *90.0% *16,355.0 *90.0% Akron, Ohio 4 4 Continental A.G.# *11,325.0 *28.5% *10,785.0 *25.0% *10,780.0 *25.0% *11,875.0 *24.8% Hanover, Germany 5 6 Sumitomo Rubber Industries Ltd.# 6,755.1 85.7% 6,029.9 85.6% 6,051.2 86.3% 6,917.7 87.3% Kobe, Japan 6 5 Pirelli & C. S.p.A.# 3 6,034.2 100.0% 6,380.0 100.0% 6,933.6 100.0% 7,992.2 ??? Milan, Italy 7 7 Hankook Tire Co. Ltd. *5,535.0 *92.0% 5,008.7 91.6% *5,320.0 *90.0% 5,595.4 88.0% Seoul, South Korea 8 8 Yokohama Rubber Co. -

Commercial Truck Tires 2019 Product Guide

COMMERCIAL TRUCK TIRES 2019 PRODUCT GUIDE www.gititrucktires.com COMMERCIAL TRUCK TIRES 5049001-10-19 GIT 18014 Giti TBR Brand Intro Page AD.r11.catalog.qxp_8.5x11 10/9/18 6:00 PM Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS World Class Technology & Quality 1 Social Responsibility 3 Technologies 4 Market Segments 5 Product Line 7 Comparison Chart 9 LONG HAUL GSL229 FS 12 GDL651 FS 13 GDL633 FS 14 GTL922 FS 15 GTL933 FS 16 REGIONAL HAUL GSR231 FS 18 GDL633 FS 19 GTL933 FS 20 GT867 21 GSR225 22 GTL919 23 GAL817 24 www.gititrucktires.com GDR652 25 GDR621 26 GDR638 27 MIXED SERVICE GAM835 29 It’s time GAM851 30 GDM635 31 GDM686 32 to talk about URBAN | LIGHT DUTY GAL817 34 GSR225 35 the elephant GDR638 36 GTL919 37 Introducing GT RADIAL in the road. Giti Commercial Truck Tires GSL213 FS 39 GT279 40 GDR639 41 Technical Data & Resources 42 Designations, Load, & Speed Index 43 Tire Pressure Management 44 Recommended Load & Inflation Table 45 Limited Warranty 53 Limited Casing Warranty 54 WORLD CLASS TECHNOLOGY & QUALITY AAGGlolobbaalTlTireireCoCmompapnayny A GlobalTire Company GitiGiti Tire (Canada) Ltd. R&D Center GitiGiti Tire (Canada) Ltd. USAR&D Center OUR DIVERSEWORKFORCE Giti Tire USA Giti Tire (USA) Ltd. Manufacturing REPRESENTS MOUOREDTIHVAERNSEWORKFORCE GitiGiti Tire (Canada) Ltd.Giti Tire Giti Tire (USA) Ltd. (USA)Manufacturing Ltd. R&D Center UKUK (MIRA) 50 NATIONALRITEIEPSRESENTS MORETHAN R&D Center (USA) Ltd. USA UKUK (MIRA) 50 NATIONALITIES Hanover,R&D Germany Center OUR DIVERSEWORKFORCE Giti Tire GitiGiti Tire (UK) Ltd. Giti Tire (USA) Ltd. Manufacturing Hanover, Germany REPRESENTS MORETHAN (USA) Ltd.Giti Tire (Europe)GitiGiti Tire (UK) Ltd. -

2020-Giti-Corporate

COMPANY & BRAND OVERVIEW Scan to view the Giti Tire Global WebsiteENJOY DRIVING A New Decade of Excitement and Success www.giti.com A Singapore-Based Global Tire Company With its roots going back more than 65 years in the tire industry, Giti Tire understands the requisites of being a resilient and consistent tire manufacturer in the highly competitive and fast changing marketplace, and has the necessary resources in place. Today, the Giti business platform fully integrates its worldwide manufacturing and R&D footprint, and innovative sales, marketing, and distribution channels together with its global motorsports activities to assure its future growth. 2019 Revenue Offices Singapore, China, Indonesia, U.S., Canada, U.K., Germany, 3.1 Billion USD 12 France, Dubai, Malaysia, Italy, and Brazil More than R&D and Tire Testing Centers 4 R&D in China, the U.S., Employees 5 Germany, Indonesia, and 1 Tire 33,000 Worldwide Testing Center in the UK More than Manufacturing Plants Point of Sales 6 in China, 1 in Indonesia, In more than 8 and 1 in the U.S. 70,000 130 countries Discover More: www.giti.com/en-us/about-us 1 2 ENJOY DRIVING These simple two words are more than just an expression: they express the passion of Giti Tire and how the company aspires to be a positive part of every driver's experience. Whether you are a mother driving their family to school or someone transporting goods across the country for business, Giti always hopes to present the best product and service to Enjoy Driving. 3 4 Comprehensive Tire Range Passenger Car Tires -

Truck-And-Fleet-Cove

VEHICLES /TECH /TRANSPOR TATION/ LOGISTICS O 61/FEBRUARY 2O19 PUBLICATION LICENSED BY DUBAI PRODUCTION CITY MIDDLE EAST GITI IS READY FOR ANYTHING Giti Tire’s Chris Bloor on the global rise of the Singapore company THE NEW LIMO NISSAN IMS: A SEDAN ON STILTS OR A LIMO CROSSOVER? 00_Cover.indd 1 1/30/19 5:44 PM FMX_CMME_FLAT_RESIZED.pdf 1 1/30/19 9:56 AM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 00_Cover.indd 2 1/30/19 5:44 PM CONTENTS CONTENTS FEATURE 22 / NISSAN REINVENTING Nissan takes a revolutionary new look at the limo. ALSO THIS ISSUE … NETWORK 06 / NEWS FROM THE MONTH 06 12 Agility inaugurates new hub inside the ‘key market’ of Bahrain. LAUNCHES 12 / CADI-ATTACK The new V6-powered ATS coupe from Cadillac arrives in the market. INTERVIEW 14 18 14 / TAKING ON THE MARKET Giti Tires’ Chris Bloor on the company’s rise in the regional and global market. INTERVIEW 18 / LOCAL TO GLOBAL How NAFFCO has gone from the UAE to being a worldwide force in fire protection. WORKSHOP 28 / P-ZONE IS IN ZONE Pirelli introduces its premium P-Zone retail brand in the region. ENGINES 30 34 30 / DIESEL DREAMS Volvo’s engine expert Dr Staffan Lundgren on new and cleaner concepts for the diesel engine. EVENTS 34 / CRAZY CONCEPTS Hyundai introduces an exciting new vision for the car at this year’s CES 2019. FEBRUARY 2019 TRUCK&FLEET ME 01 01_Contents.indd 1 1/30/19 5:47 PM WELCOME GROUP MANAGING DIRECTOR RAZ ISLAM [email protected] +971 4 375 5483 EDITORIAL DIRECTOR VIJAYA CHERIAN [email protected] +971 4 375 5472 EDITORIAL EDITOR STEPHEN WHITE [email protected] -

INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS and FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT in the CHARLOTTE REGION CHARLOTTE REGION FDI: by the Numbers

INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS AND FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT IN THE CHARLOTTE REGION CHARLOTTE REGION FDI: By the Numbers More than More than More than $1.6B +15% 1,000 40 75,000 Of investment US Exports International Countries People Since 2017 from the Businesses employed by Charlotte foreign fi rms Region Since 2017 CharlotteRegion.com 2 INTRODUCTION The Charlotte Region is global. More than 1,000 international companies representing more than 40 countries and 250,000 foreign-born individuals and families call the region home. The continuing relocation and expansion of businesses and people contributes to increasing international connections and partnerships. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) remains crucial for the prosperity of the Charlotte Region. The strategic location of the Charlotte Douglas International Airport coupled with an intermodal faciltiy and proximity to the ports of Wilmington and Charleston, connect the region to major global business hubs including London, Munich, Frankfurt, and Toronto. The Charlotte Region is ready to welcome more international companies for ongoing global engagement and economic growth within a culturally diverse environment. Sources: Charlotte Regional Business Alliance Analysis, Charlotte Douglas International Airport, U.S Census Bureau, Brookings Institution, Forbes CharlotteRegion.com 3 INTERNATIONAL COMPANIES REPRESENTATION IN THE WORLD International companies in the Charlotte Region employ over 75,000 people, or 5.4% of total regional employment. Of the workforce employed by international businesses,