Parrot Claylicks: Distribution, Patterns of Use and Ecological Correlates from a Parrot Assemblage in Southeastern Peru

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TAG Operational Structure

PARROT TAXON ADVISORY GROUP (TAG) Regional Collection Plan 5th Edition 2020-2025 Sustainability of Parrot Populations in AZA Facilities ...................................................................... 1 Mission/Objectives/Strategies......................................................................................................... 2 TAG Operational Structure .............................................................................................................. 3 Steering Committee .................................................................................................................... 3 TAG Advisors ............................................................................................................................... 4 SSP Coordinators ......................................................................................................................... 5 Hot Topics: TAG Recommendations ................................................................................................ 8 Parrots as Ambassador Animals .................................................................................................. 9 Interactive Aviaries Housing Psittaciformes .............................................................................. 10 Private Aviculture ...................................................................................................................... 13 Communication ........................................................................................................................ -

CNC/IUGG: 2019 Quadrennial Report

CNC/IUGG: 2019 Quadrennial Report Geodesy and Geophysics in Canada 2015-2019 Quadrennial Report of the Canadian National Committee for the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics Prepared on the Occasion of the 27th General Assembly of the IUGG Montreal, Canada July 2019 INTRODUCTION This report summarizes the research carried out in Canada in the fields of geodesy and geophysics during the quadrennial 2015-2019. It was prepared under the direction of the Canadian National Committee for the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics (CNC/IUGG). The CNC/IUGG is administered by the Canadian Geophysical Union, in consultation with the Canadian Meteorological and Oceanographic Society and other Canadian scientific organizations, including the Canadian Association of Physicists, the Geological Association of Canada, and the Canadian Institute of Geomatics. The IUGG adhering organization for Canada is the National Research Council of Canada. Among other duties, the CNC/IUGG is responsible for: • collecting and reconciling the many views of the constituent Canadian scientific community on relevant issues • identifying, representing, and promoting the capabilities and distinctive competence of the community on the international stage • enhancing the depth and breadth of the participation of the community in the activities and events of the IUGG and related organizations • establishing the mechanisms for communicating to the community the views of the IUGG and information about the activities of the IUGG. The aim of this report is to communicate to both the Canadian and international scientific communities the research areas and research progress that has been achieved in geodesy and geophysics over the last four years. The main body of this report is divided into eight sections: one for each of the eight major scientific disciplines as represented by the eight sister societies of the IUGG. -

Factors Influencing Density of the Northern Mealy Amazon in Three Forest Types of a Modified Rainforest Landscape in Mesoamerica

VOLUME 12, ISSUE 1, ARTICLE 5 De Labra-Hernández, M. Á., and K. Renton. 2017. Factors influencing density of the Northern Mealy Amazon in three forest types of a modified rainforest landscape in Mesoamerica. Avian Conservation and Ecology 12(1):5. https://doi.org/10.5751/ACE-00957-120105 Copyright © 2017 by the author(s). Published here under license by the Resilience Alliance. Research Paper Factors influencing density of the Northern Mealy Amazon in three forest types of a modified rainforest landscape in Mesoamerica Miguel Ángel De Labra-Hernández 1 and Katherine Renton 2 1Posgrado en Ciencias Biológicas, Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, México, 2Estación de Biología Chamela, Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Jalisco, México ABSTRACT. The high rate of conversion of tropical moist forest to secondary forest makes it imperative to evaluate forest metric relationships of species dependent on primary, old-growth forest. The threatened Northern Mealy Amazon (Amazona guatemalae) is the largest mainland parrot, and occurs in tropical moist forests of Mesoamerica that are increasingly being converted to secondary forest. However, the consequences of forest conversion for this recently taxonomically separated parrot species are poorly understood. We measured forest metrics of primary evergreen, riparian, and secondary tropical moist forest in Los Chimalapas, Mexico. We also used point counts to estimate density of Northern Mealy Amazons in each forest type during the nonbreeding (Sept 2013) and breeding (March 2014) seasons. We then examined how parrot density was influenced by forest structure and composition, and how parrots used forest types within tropical moist forest. -

Illegal Trade of the Psittacidae in Venezuela

Illegal trade of the Psittacidae in Venezuela A DA S ÁNCHEZ-MERCADO,MARIANNE A SMÜSSEN,JON P AUL R ODRÍGUEZ L ISANDRO M ORAN,ARLENE C ARDOZO-URDANETA and L ORENA I SABEL M ORALES Abstract Illegal wildlife trade is one of the major threats to trade involves avian species, poached to supply both domes- Neotropical psittacids, with nearly % of species targeted tic and international demand for pets (Rosen & Smith, for the illegal pet trade. We analysed the most comprehen- ). Among birds, Neotropical psittacids are of primary sive data set on illegal wildlife trade currently available for conservation concern, with nearly % of species affected Venezuela, from various sources, to provide a quantitative by poaching for the illegal pet trade (Olah et al., ). assessment of the magnitude, scope and detectability of The data used to measure the magnitude of the illegal pet the trade in psittacids at the national level. We calculated trade in psittacids have come from four main sources: seiz- a specific offer index (SO) based on the frequency of ure records and surveys of trappers (Cantú Guzmán et al., which each species was offered for sale. Forty-seven species ), literature reviews (Pires, ; Alves et al., ), dir- of psittacids were traded in Venezuela during –,of ect observation in markets (Herrera & Hennessey, ; which were non-native. At least , individuals were Gastañaga et al., ; Silva Regueira & Bernard, ), traded, with an overall extraction rate of , individuals and observation of the proportion of nest cavities poached per year ( years of accumulated reports). Amazona (Wright et al., ; Pain et al., ; Zager et al., ). ochrocephala was the most frequently detected species Each source has a unique geographical and taxonomic (SO = .), with the highest extraction rate (, indivi- coverage and evaluates different aspects of the market duals per year), followed by Eupsittula pertinax (SO = .) chain. -

Rødbrystet Conure

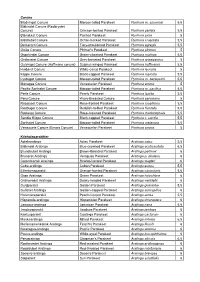

Conure Blodvinget Conure Maroon -tailed Parakeet Pyrrhura m. souancei 5,5 Blåkindet Conure (Rødbrystet Conure) Crimson-bellied Parakeet Pyrrhura perlata 5,5 Blånakket Conure Painted Parakeet Pyrrhura picta 5 Blåstrubet Conure Ochre-marked Parakeet Pyrrhura cruentata 5,5 Demerara Conure Fiery-shouldered Parakeet Pyrrhura egregia 5,5 Goiás Conure Pfrimer's Parakeet Pyrrhura pfrimeri 5 Grønkindet Conure Green-cheeked Parakeet Pyrrhura molinae 5,5 Gråbrystet Conure Grey-breasted Parakeet Pyrrhura griseipectus 5 Gulvinget Conure (Hoffmans conure) Sulphur-winged Parakeet Pyrrhura hoffmanni 5,5 Hvidøret Conure White-eared Parakeet Pyrrhura leucotis 5 Klippe Conure Black-capped Parakeet Pyrrhura rupicola 5,5 Lysbuget Conure Maroon-tailed Parakeet Pyrrhura m. berlepschi 5,5 Monagas Conure Venezuelan Parakeet Pyrrhura emma 5 Pacific Sorthalet Conure Maroon-tailed Parakeet Pyrrhura m. pacifica 5,5 Perle Conure Pearly Parakeet Pyrrhura lepida 5,5 Peru Conure Wavy-Breasted Conure Pyrrhura peruviana 5 Rosaisset Conure Rose-fronted Parakeet Pyrrhura roseifrons 5,5 Rødbuget Conure Reddish-bellied Parakeet Pyrrhura frontalis 5,5 Rødisset Conure Rose-crowned Parakeet Pyrrhura rhodocephala 5,5 Sandia Klippe Conure Black-capped Parakeet Pyrrhura r. sandia 5,5 Sorthalet Conure Maroon-tailed Parakeet Pyrrhura melanura 5,5 Venezuela Conure (Emma Conure) Venezuelan Parakeet Pyrrhura emma 5 Kilehaleparakitter Aztekaratinga Aztec Parakeet Aratinga astec 5,5 Blåkindet Aratinga Blue-crowned Parakeet Aratinga acuticaudata 6,5 Brunstrubet Aratinga Brown-throated Parakeet -

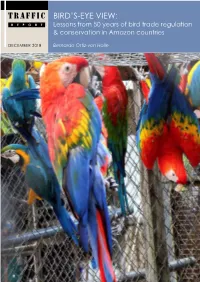

TRAFFIC Bird’S-Eye View: REPORT Lessons from 50 Years of Bird Trade Regulation & Conservation in Amazon Countries

TRAFFIC Bird’s-eye view: REPORT Lessons from 50 years of bird trade regulation & conservation in Amazon countries DECEMBER 2018 Bernardo Ortiz-von Halle About the author and this study: Bernardo Ortiz-von Halle, a biologist and TRAFFIC REPORT zoologist from the Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia, has more than 30 years of experience in numerous aspects of conservation and its links to development. His decades of work for IUCN - International Union for Conservation of Nature and TRAFFIC TRAFFIC, the wildlife trade monitoring in South America have allowed him to network, is a leading non-governmental organization working globally on trade acquire a unique outlook on the mechanisms, in wild animals and plants in the context institutions, stakeholders and challenges facing of both biodiversity conservation and the conservation and sustainable use of species sustainable development. and ecosystems. Developing a critical perspective The views of the authors expressed in this of what works and what doesn’t to achieve lasting conservation goals, publication do not necessarily reflect those Bernardo has put this expertise within an historic framework to interpret of TRAFFIC, WWF, or IUCN. the outcomes of different wildlife policies and actions in South America, Reproduction of material appearing in offering guidance towards solutions that require new ways of looking at this report requires written permission wildlife trade-related problems. Always framing analysis and interpretation from the publisher. in the midst of the socioeconomic and political frameworks of each South The designations of geographical entities in American country and in the region as a whole, this work puts forward this publication, and the presentation of the conclusions and possible solutions to bird trade-related issues that are material, do not imply the expression of any linked to global dynamics, especially those related to wildlife trade. -

Native Trees of Mexico: Diversity, Distribution, Uses and Conservation

Native trees of Mexico: diversity, distribution, uses and conservation Oswaldo Tellez1,*, Efisio Mattana2,*, Mauricio Diazgranados2, Nicola Kühn2, Elena Castillo-Lorenzo2, Rafael Lira1, Leobardo Montes-Leyva1, Isela Rodriguez1, Cesar Mateo Flores Ortiz1, Michael Way2, Patricia Dávila1 and Tiziana Ulian2 1 Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala, Av. De los Barrios 1, Los Reyes Iztacala Tlalnepantla, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Estado de México, Mexico 2 Wellcome Trust Millennium Building, RH17 6TN, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Ardingly, West Sussex, United Kingdom * These authors contributed equally to this work. ABSTRACT Background. Mexico is one of the most floristically rich countries in the world. Despite significant contributions made on the understanding of its unique flora, the knowledge on its diversity, geographic distribution and human uses, is still largely fragmented. Unfortunately, deforestation is heavily impacting this country and native tree species are under threat. The loss of trees has a direct impact on vital ecosystem services, affecting the natural capital of Mexico and people's livelihoods. Given the importance of trees in Mexico for many aspects of human well-being, it is critical to have a more complete understanding of their diversity, distribution, traditional uses and conservation status. We aimed to produce the most comprehensive database and catalogue on native trees of Mexico by filling those gaps, to support their in situ and ex situ conservation, promote their sustainable use, and inform reforestation and livelihoods programmes. Methods. A database with all the tree species reported for Mexico was prepared by compiling information from herbaria and reviewing the available floras. Species names were reconciled and various specialised sources were used to extract additional species information, i.e. -

Environmental Sensitivity Index Guidelines Version 2.0

NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS ORCA 115 Environmental Sensitivity Index Guidelines Version 2.0 October 1997 Seattle, Washington noaa NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION National Ocean Service Office of Ocean Resources Conservation and Assessment National Ocean Service National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration U.S. Department of Commerce The Office of Ocean Resources Conservation and Assessment (ORCA) provides decisionmakers comprehensive, scientific information on characteristics of the oceans, coastal areas, and estuaries of the United States of America. The information ranges from strategic, national assessments of coastal and estuarine environmental quality to real-time information for navigation or hazardous materials spill response. Through its National Status and Trends (NS&T) Program, ORCA uses uniform techniques to monitor toxic chemical contamination of bottom-feeding fish, mussels and oysters, and sediments at about 300 locations throughout the United States. A related NS&T Program of directed research examines the relationships between contaminant exposure and indicators of biological responses in fish and shellfish. Through the Hazardous Materials Response and Assessment Division (HAZMAT) Scientific Support Coordination program, ORCA provides critical scientific support for planning and responding to spills of oil or hazardous materials into coastal environments. Technical guidance includes spill trajectory predictions, chemical hazard analyses, and assessments of the sensitivity of marine and estuarine environments to spills. To fulfill the responsibilities of the Secretary of Commerce as a trustee for living marine resources, HAZMAT’s Coastal Resource Coordination program provides technical support to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency during all phases of the remedial process to protect the environment and restore natural resources at hundreds of waste sites each year. -

October 2003 SOCIETY

ISSN 0739-4934 NEWSLETTER HISTORY OF SCIENCE VOLUME 32 NUMBER 4 October 2003 SOCIETY those with no interest in botany, the simple beauty of the glass is enough. Natural History Delights in Cambridge From modern-life in glass to long-ago life, it’s only a short walk. The museum houses ant to discuss dinosaurs, explore microfossils of some of the Earth’s earliest life Wancient civilizations, learn wild- forms, as well as fossil fish and dinosaurs – flower gardening, or study endangered such as the second ever described Triceratops, species? If variety is the spice of life, then and the world’s only mounted Kronosaurus, a the twenty-one million specimens at the 42-foot-long prehistoric marine reptile. Harvard Museum of Natural History show a Among its 90,000 zoological specimens the museum bursting with life, much of it unnat- museum also has the pheasants once owned urally natural. by George Washington. And many of the The museum will be the site of the opening mammal collections were put together in the reception for the 2003 HSS annual meeting. 19th century by “lions” in the history of sci- The reception begins at 7 p.m. Thursday, 20 ence, like Louis Agassiz. November, and tickets will be available at the Much of the museum’s collection of rocks and meeting registration desk. Buses will run from ores is the result of field work, but the museum the host hotel to the museum. houses not only that which has been dug up, but The Harvard MNH is an ideal spot for his- also that which has fallen out of the sky. -

South Africa: Magoebaskloof and Kruger National Park Custom Tour Trip Report

SOUTH AFRICA: MAGOEBASKLOOF AND KRUGER NATIONAL PARK CUSTOM TOUR TRIP REPORT 24 February – 2 March 2019 By Jason Boyce This Verreaux’s Eagle-Owl showed nicely one late afternoon, puffing up his throat and neck when calling www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | TRIP REPORT South Africa: Magoebaskloof and Kruger National Park February 2019 Overview It’s common knowledge that South Africa has very much to offer as a birding destination, and the memory of this trip echoes those sentiments. With an itinerary set in one of South Africa’s premier birding provinces, the Limpopo Province, we were getting ready for a birding extravaganza. The forests of Magoebaskloof would be our first stop, spending a day and a half in the area and targeting forest special after forest special as well as tricky range-restricted species such as Short-clawed Lark and Gurney’s Sugarbird. Afterwards we would descend the eastern escarpment and head into Kruger National Park, where we would make our way to the northern sections. These included Punda Maria, Pafuri, and the Makuleke Concession – a mouthwatering birding itinerary that was sure to deliver. A pair of Woodland Kingfishers in the fever tree forest along the Limpopo River Detailed Report Day 1, 24th February 2019 – Transfer to Magoebaskloof We set out from Johannesburg after breakfast on a clear Sunday morning. The drive to Polokwane took us just over three hours. A number of birds along the way started our trip list; these included Hadada Ibis, Yellow-billed Kite, Southern Black Flycatcher, Village Weaver, and a few brilliant European Bee-eaters. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Phylogeography of the Military Macaw (Ara Militaris) and the Great Green Macaw (A

The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 127(4):661–669, 2015 PHYLOGEOGRAPHY OF THE MILITARY MACAW (ARA MILITARIS) AND THE GREAT GREEN MACAW (A. AMBIGUUS) BASED ON MTDNA SEQUENCE DATA JESSICA R. EBERHARD,1,5 EDUARDO E. IÑIGO-ELIAS,2 ERNESTO ENKERLIN-HOEFLICH,3 AND E. PAÙL CUN4 ABSTRACT.—The Military Macaw (Ara militaris) and the Great Green Macaw (A. ambiguus) are species whose close relationship is reflected in their morphological similarity as well as their geographic ranges. Military Macaws have a disjunct distribution, found in Mexico as well as several areas in South America, while Great Green Macaws have two or more disjunct populations from Honduras to eastern Ecuador. We used mitochondrial sequence data to examine the phylogenetic relationships between these two species, and also among representative samples across their ranges. Our data clearly support recognition of the two species as being distinct evolutionary lineages, and while we found significant phylogeographic structure within A. militaris (between samples collected in eastern and western Mexico), we did not find any evidence of lineage divergence between A. ambiguus from Costa Rica and Ecuador. Received 12 December 2014. Accepted 30 May 2015. Key words: disjunct distribution, Great Green Macaw, Military Macaw, phylogeny, phylogeography. The Military Macaw (Ara militaris) and the South America, primarily east of the Andes from Great Green Macaw (A. ambiguus), sometimes northwestern Colombia and northwestern Vene- named Buffon’s Macaw, are both large macaws zuela to north-western Argentina (Ridgway 1916; that are closely related and possibly conspecific Chapman 1917; Alvarez del Toro 1980; Ridgely (Fjeldså et al. 1987, Collar et al.