Conversations with Kafka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Klaus Johann Bibliographie Der Sekundärliteratur Zu Johannes Urzidil (Stand: 3

Klaus Johann Bibliographie der Sekundärliteratur zu Johannes Urzidil (Stand: 3. XI. 2010) 1. a.d. (KK): Die siebzehn Reisen Goethes nach Böhmen. [Rezension der erweiterten Neuauflage von „Goethe in Böhmen“.] In: Aufbau (New York). 16. VII. 1982. 2. A.S.: Johannes Urzidil liest. Zimmertheater Heddy Maria Wettstein. In: Die Tat. 17. X. 1970. 3. Abendroth, Friedrich [i.e. Friedrich Weigend-Abendroth] : „Die Erbarmungen Gottes“. [Rezension der Neuausgabe von „Goethe in Böhmen“.] In: Die Furche. Nr. 38. 22. IX. 1962. S.11. 4. Abendroth, Friedrich: Erzählen ist nicht mehr erlaubt? In: Echo der Zeit. 30. X. 1966. 5. Abendroth, Friedrich: Ein böhmisches Buch. [Rezension von Johannes Urzidil, „Die verlorene Geliebte“.] In: Die Furche. Nr.39. 22. IX. 1956. Beilage „Der Krystall“. S.3. 6. Adam, Franz: Mit Franz Kafka saß er im Café. Tagung des Ostdeutschen Kulturrats über Johannes Urzidil. In: Kulturpolitische Korrespondenz. 1037. 5. April 1998. S.11-13. 7. Adler, H. G.: Die Dichtung der Prager Schule. [EA: 1976.] Vorw. v. Jeremy Adler. Wuppertal u. Wien: Arco 2010. ( = Coll’Arco.<FA>3) 8. ag: Ein Dichter Böhmens. Zu einer Vorlesung Johannes Urzidils. In: Stutt- garter Zeitung. 22. XI. 1962. 9. Ahl, Herbert: Ein Historiker seiner Visionen. Johannes Urzidil . In: H.A.: Litera- rische Portraits. München u. Wien: Langen Müller 1962. S.164-172. 10. ak: Vergangenes. [Rezension der Heyne-Taschenbuchausgabe von „Prager Triptychon“.] In: Deutsche Tagespost. 27. VI. 1980. 11. Albers, Heinz: Wie der Freund ihn sah. Johannes Urzidil im Hamburg Cen- trum über Kafka. In: Hamburger Abendblatt. 2. X. 1970. 12. Alexander, Manfred: Einleitung. In: M.A. (Hg.): Deutsche Gesandtschaftsbe- richte aus Prag. -

Das 20. Jahrhundert 252

Das 20. Jahrhundert 252 Prominent 2 ! Bekannte Schriftsteller, Kritiker und Künstler Antiquariat Frank Albrecht · [email protected] 69198 Schriesheim · Mozartstr. 62 · Tel.: 06203/65713 Das 20. Jahrhundert 252 D Verlag und A Prominent 2 ! Bekannte Schriftsteller, S Antiquariat Kritiker und Künstler 2 Frank 0. J A Albrecht H Inhalt R H Belletristik ....................................................................... 1 69198 Schriesheim U Sekundärliteratur ........................................................... 31 Mozartstr. 62 N Kunst ............................................................................. 35 Register ......................................................................... 55 Tel.: 06203/65713 D FAX: 06203/65311 E Email: R [email protected] T USt.-IdNr.: DE 144 468 306 D Steuernr. : 47100/43458 Die Abbildung auf dem Vorderdeckel A zeigt eine Original-Zeichnung von S Joachim Ringelnatz (Katalognr. 113). 2 0. J A H Spezialgebiete: R Autographen und H Widmungsexemplare U Belletristik in Erstausgaben N Illustrierte Bücher D Judaica Kinder- und Jugendbuch E Kulturgeschichte R Unser komplettes Angebot im Internet: Kunst T http://www.antiquariat.com Politik und Zeitgeschichte Russische Avantgarde D Sekundärliteratur und Bibliographien A S Gegründet 1985 2 0. Geschäftsbedingungen J Mitglied im Alle angebotenen Bücher sind grundsätzlich vollständig und, wenn nicht an- P.E.N.International A ders angegeben, in gutem Erhaltungszustand. Die Preise verstehen sich in Euro und im Verband H (€) inkl. Mehrwertsteuer. -

Common Sayings and Expressions in Kafka Hartmut Binder

Document generated on 09/25/2021 10:25 p.m. TTR Traduction, terminologie, re?daction Common Sayings and Expressions in Kafka Hartmut Binder Kafka pluriel : réécriture et traduction Volume 5, Number 2, 2e semestre 1992 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/037123ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/037123ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Association canadienne de traductologie ISSN 0835-8443 (print) 1708-2188 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Binder, H. (1992). Common Sayings and Expressions in Kafka. TTR, 5(2), 41–105. https://doi.org/10.7202/037123ar Tous droits réservés © TTR: traduction, terminologie, rédaction — Les auteurs, This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit 1992 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Common Sayings and Expressions in Kafka Hartmut Binder Translation by Iris and Donald Bruce, University of Alberta "Bild, nur Büd"1 [Images, only images] Proverbial sayings are pictorially formed verbal phrases2 whose wording, as it has been handed down, is relatively fixed and whose meaning is different from the sum of its constituent parts. As compound expressions, they are to be distinguished from verbal metaphors; as syntactically dependant constructs, which gain ethical meaning and the status of objects only through their embedding in discursive relationships, they are to be differentiated from proverbs. -

Kafka's Uncle

Med Humanities: first published as 10.1136/mh.26.2.85 on 1 December 2000. Downloaded from J Med Ethics: Medical Humanities 2000;26:85–91 Kafka’s uncle: scenes from a world of trust infected by suspicion Iain Bamforth General Practitioner, Strasbourg, France Abstract well documented fraught relationship. But the title What happens when we heed a call? Few writers have figure of the collection—the country doctor— been as suspicious of their vocation as Franz Kafka honours a diVerent relative altogether, his uncle. (1883–1924). His story, A Country Doctor, (1919) Siegfried Löwy was born in 1867, elder ostensibly about a night visit to a patient that goes half-brother to Kafka’s mother and, following his badly wrong, suggests a modern writer’s journey to the MD, possessor of the only doctorate in the family heart of his work. There he discovers that trust, like the until his nephew. Significantly, Franz often thought tradition which might sustain him, is blighted. This of himself as a Löwy rather than a Kafka: his diary essay also examines Kafka’s attitude to illness and the entry for 25 December 1911 contains a long list of medical profession, and his close relationship with his colourful matrilineal begats, including a reference uncle, Siegfried Löwy (1867–1942), a country doctor to his maternal great-grandfather, who was a mira- in Moravia. cle rabbi. “In Hebrew my name is Amschel, like my (J Med Ethics: Medical Humanities 2000;26:85–91) mother’s maternal grandfather, whom my mother, Keywords: Franz Kafka; German literature; trust; suspi- who was six years old when he died, can remember cion; doctor-baiting; negotiation as a very pious and learned man with a long, white beard. -

Rudolf Abraham

Rudolf Abraham - Die Theorie des modernen Sozialismus Mark Abramowitsch - Hauptprobleme der Soziologie Alfred Adler (1870 - 1937) Hermann Adler (1839 - 1911) Max Adler (1873 - 1937) - alles Kurt Adler-Löwenstein (1885 - 1932) - Soziologische und schulpolitische Grundfragen, Am anderen Ufer, d.i. der Verlag „Am anderen Ufer“ von Otto Rühle und Alice Rühle-Gerstel, in dem u. a. 1924 die Blätter für sozialistische Erziehung erschienen sowie 1926/27 die Schriftenreihe Schwer erziehbare Kinder Meir Alberton - Birobidschan, die Judenrepublik Siegfried Alkan (1858 - 1941) Bruno Altmann (1878 - 1943) - Vor dem Sozialistengesetz Martin Andersen-Nexø (1869 - 1954) - Proletariernovellen Frank Arnau (1894 -1976) - Der geschlossene Ring Käthe (Kate) Asch (1887 - ?) - Die Lehre Charles Fouriers Nathan Asch (1902 - 1964) - Der 22. August Schalom Asch (1880 - 1957) - Onkel Moses, Der elektrische Stuhl Wladimir Astrow (1885 - 1944) - Illustrierte Geschichte der Russischen Revolution Raoul Auernheimer (1876 - 1948) Siegfried Aufhäuser (1884 - 1969) - alles B Julius Bab (1880 - 1955) – alles Isaak Babel (1894 - 1941) - Budjonnys Reiterarmee Michail A. Bakunin (1814 -1876) - Gott und der Staat sowie weitere Schriften Angelica Balabanoff (1878 - 1965) - alles Béla Balázs (1884 - 1949) - Der Geist des Films Henri Barbusse (1873 - 1935) - 159 Millionen, Die Henker, Ein Mitkämpfer spricht, Das Feuer Ernst Barlach (1870 - 1938) Max Barthel (Konrad Uhle) (1893 - 1975) - Die Mühle zum toten Mann Adolpe Basler (1869 - 1951) - Henry Matisse Ludwig Bauer (1876 - 1935) -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

Animal Studies Ecocriticism and Kafkas Animal Stories 4

Citation for published version: Goodbody, A 2016, Animal Studies: Kafka's Animal Stories. in Handbook of Ecocriticism and Cultural Ecology. Handbook of English and American Studies, vol. 2, De Gruyter, Berlin, pp. 249-272. Publication date: 2016 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication University of Bath Alternative formats If you require this document in an alternative format, please contact: [email protected] General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 Animal Studies: Kafka’s Animal Stories Axel Goodbody Franz Kafka, who lived in the city of Prague as a member of the German-speaking Jewish minority, is usually thought of as a quintessentially urban author. The role played by nature and the countryside in his work is insignificant. He was also no descriptive realist: his domain is commonly referred to as the ‘inner life’, and he is chiefly remembered for his depiction of outsider situations accompanied by feelings of inadequacy and guilt, in nightmarish scenarios reflecting the alienation of the modern subject. Kafka was only known to a small circle of when he died of tuberculosis, aged 40, in 1924. However, his enigmatic tales, bafflingly grotesque but memorably disturbing because they resonate with readers’ own experiences, anxieties and dreams, their sense of marginality in family and society, and their yearning for self-identity, rapidly acquired the status of world literature after the Holocaust and the Second World War. -

München Liest

Die verbrannten Dichter: „Die Waffen nieder!“ (Bertha von Suttner) Nathan Asch - Martin Andersen-Nexö - Ernst Barlach - Oskar Baum - Vicki Baum - Johannes R. Becher - Walter Benjamin - Martin Beradt - Eduard Bernstein - Franz Blei - Bertolt Brecht - Willi Bredel - Joseph Breitbach - Max Brod - Ferdinand Bruckner - Elias Canetti - Veza Canetti - Elisabeth Castonier - Franz Th. Csokor - Alfred Döblin - John Dos Passos - Kasimir Edschmid - Hans Fallada - Lion Feuchtwanger - Marieluise Fleißer - Bruno Frank - Leonhard Frank - Anna Freud - Sigmund Freud - Egon Friedell - Richard Friedenthal -Claire Goll - Maxim Gorki - Oskar Maria Graf - Karl Grünberg - Willy Haas - Hans Habe - Jakob Haringer - Walter Wenn Sie fünf Minuten aus einem Hasenclever - Georg Hermann - Franz Hessel - “verbrannten Buch” vorlesen möchten, Ödön von Horvath - Oskar Jellinek - Erich Kästner - rufen Sie bitte an unter Franz Kafka - Mascha Kaleko - Gina Kaus - Hermann 089 - 157 32 19. Kesten - Irmgard Keun - Egon Erwin Kisch - Klabund - Annette Kolb - Gertrud Kolmar - Paul Kornfeld - Theodor Kramer - Else Lasker-Schüler - Maria Veranstalter: Leitner - Theodor Lessing - Jack London - Emil - Institut für Kunst und Forschung, München, Ludwig - Heinrich Mann - Klaus Mann - Thomas Wolfram P. Kastner, Tel. 089 - 157 32 19 Mann - Valeriu Marcu - Walter Mehring - Konrad Merz - Max Mohr - Erich Mühsam - Hans Natonek - Mitveranstalter: - Landeshauptstadt München, Max Hermann Neiße - Alfred Neumann - Robert Kulturreferat und Referat fur Bildung und Sport Neumann - Leo Perutz - Carl -

Walt Whitman

CONSTRUCTING THE GERMAN WALT WHITMAN CONSTRUCTING THE GERMAN Walt Whitman BY WALTER GRUNZWEIG UNIVERSITY OF IOWA PRESS 1!11 IOWA CITY University oflowa Press, Iowa City 52242 Copyright © 1995 by the University of Iowa Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Design by Richard Hendel No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed on acid-free paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gri.inzweig, Walter. Constructing the German Walt Whitman I by Walter Gri.inzweig. p. em. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-87745-481-7 (cloth), ISBN 0-87745-482-5 (paper) 1. Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892-Appreciation-Europe, German-speaking. 2. Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892- Criticism and interpretation-History. 3. Criticism Europe, German-speaking-History. I. Title. PS3238.G78 1994 94-30024 8n' .3-dc2o CIP 01 00 99 98 97 96 95 c 5 4 3 2 1 01 00 99 98 97 96 95 p 5 4 3 2 1 To my brother WERNER, another Whitmanite CONTENTS Acknowledgments, ix Abbreviations, xi Introduction, 1 TRANSLATIONS 1. Ferdinand Freiligrath, Adolf Strodtmann, and Ernst Otto Hopp, 11 2. Karl Knortz and Thomas William Rolleston, 20 3· Johannes Schlaf, 32 4· Karl Federn and Wilhelm Scholermann, 43 5· Franz Blei, 50 6. Gustav Landauer, 52 7· Max Hayek, 57 8. Hans Reisiger, 63 9. Translations after World War II, 69 CREATIVE RECEPTION 10. Whitman in German Literature, 77 11. -

Franz Werfel Papers, 1910-1944 LSC.0512

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt800007v5 No online items Franz Werfel papers, 1910-1944 LSC.0512 Finding aid prepared by Lilace Hatayama; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] Online finding aid last updated 15 December 2017. Franz Werfel papers, 1910-1944 LSC.0512 1 LSC.0512 Title: Franz Werfel papers Identifier/Call Number: LSC.0512 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 18.5 linear feet(37 boxes and 1 oversize box) Date: 1910-1944 Abstract: Franz Werfel (1890-1945) was one of the founders of the expressionist movement in German literature. In 1940, he fled the Nazis and settled in the U.S. He wrote one of his most popular novels, Song of Bernadette, in 1941. The collection consists of materials found in Werfel's study at the time of his death. Includes correspondence, manuscripts, clippings and printed materials, pictures, artifacts, periodicals, and books. Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance through our electronic paging system using the request button located on this page. Werfel's desk on permanent loan to the Villa Aurora in Pacific Palisades. Creator: Werfel, Franz, 1890-1945 Conditions Governing Reproduction and Use Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library Special Collections. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. -

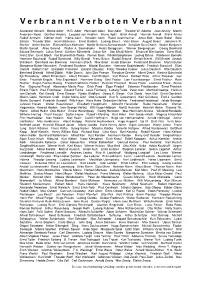

V E R B R a N N T V E R B O T E N V E R B a N

V e r b r a n n t V e r b o t e n V e r b a n n t Alexander Abusch Bruno Adler H.G. Adler Hermann Adler Max Adler Theodor W. Adorno Jean Améry Martin Andersen Nexö Günther Anders Leopold von Andrian Bruno Apitz Erich Arendt Hannah Arendt Frank Arnau Rudolf Arnheim Nathan Asch Käthe Asch Schalom Asch Raoul Auernheimer Julius Bab Isaak Babel Béla Balázs Theodor Balk Henri Barbusse Ernst Barlach Ludwig Bauer Vicki Baum August Bebel Johannes R. Becher Ulrich Becher Richard Beer-Hofmann Martin Beheim-Schwarzbach Schalom Ben-Chorin Walter Benjamin Martin Beradt Alice Berend Walter A. Berendsohn Heinz Berggruen Werner Bergengruen Georg Bernhard Eduard Bernstein Julius Berstl Günther Birkenfeld Oskar Bie Oto Bihalji-Merin Emanuel Bin-Gorion Ernst Blaß Franz Blei Ernst Bloch Ilse Blumenthal-Weiss Werner Bock Nikolai Bogdanow Ludwig Börne Waldemar Bonsels Hermann Borchardt Rudolf Borchardt Willy Brandt Franz Braun Rudolf Braune Bertolt Brecht Willi Bredel Joseph Breitbach Bernhard von Brentano Hermann Broch Max Brod Arnolt Bronnen Ferdinand Bruckner Martin Buber Margarete Buber-Neumann Ferdinand Bruckner Nikolai Bucharin Hermann Budzislawski Friedrich Burschell Elias Canetti Robert Carr Elisabeth Castonier Eduard Claudius Franz Theodor Csokor Julius Deutsch Otto Deutsch Bernhard Diebold Alfred Döblin Hilde Domin John Dos Passos Theodore Dreiser Albert Drach Kasimir Edschmid Ilja Ehrenburg Albert Ehrenstein Albert Einstein Carl Einstein Kurt Eisner Norbert Elias Arthur Eloesser Lex Ende Friedrich Engels Fritz Erpenbeck Hermann Essig Emil Faktor Lion Feuchtwanger Ernst Fischer Ruth Fischer Eugen Fischer-Baling Friedrich-Wilhelm Förster Heinrich Fraenkel Bruno Frank Leonhard Frank Bruno Frei Sigmund Freud Alexander Moritz Frey Erich Fried Egon Friedell Salomon Friedlaender Ernst Friedrich Efraim Frisch Paul Frischauer Eduard Fuchs Louis Fürnberg Ludwig Fulda Peter Gan Manfred George Hellmut von Gerlach Karl Gerold Ernst Glaeser Fjodor Gladkow Georg K. -

November/December 2012

From the Office By Daniel D. Skwire His complaints about his duties were epic, but Kafka clearly drew satisfaction from working his day job at the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute of the Kingdom of Bohemia in Prague. ITTLE KNOWN DURING HIS LIFETIME, ghastly machine to torture and execute his prisoners. And in Franz Kafka has come to be recognized as one of The Trial, a man must defend himself in court without being the greatest writers of the 20th century. His works informed of the crime he has been accused of committing. These include some of the most disturbing and enduring portraits of disillusionment, anxiety, and despair anticipate the images of modern fiction. The hero of The Metamor- subsequent horrors of mid-20th-century war and inhumanity. phosis, for example, awakens one morning to find he has been Many of the details of Kafka’s own life are scarcely more Ltransformed into a giant insect. Kafka’s short story “In the Penal cheerful. A sickly individual, he struggled with tuberculosis and Colony” features an officer in a prison camp who maintains a other illnesses before dying at the age of 40. His relationships 20 CONTINGENCIES NOV | DEC.12 WWW.CONTINGENCIES.ORG of Franz Kafka Kafka's desk at the Worker's Accident Insurance Institute in Prague with women were unsuccessful, and he never married despite their occupations. An examination of Kafka’s insurance career being engaged on several occasions. He lived with his parents humanizes him and sheds light on his writing by showing his for most of his life and complained bitterly that his work in the dedication, accomplishments, and sense of humor alongside his insurance profession kept him from his true calling of writing—a many frustrations.