Antonello Da Messina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Pages from the Book

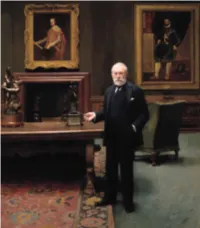

AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 2 16/3/21 18:49 What’s Mine Is Yours Private Collectors and Public Patronage in the United States Essays in Honor of Inge Reist edited by Esmée Quodbach AF Whats Mine is Yours.indb 3 16/3/21 18:49 first published by This publication was organized by the Center for the History of Collecting at The Frick Collection and Center for the History of Collecting Frick Art Reference Library, New York, the Centro Frick Art Reference Library, The Frick Collection de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH), Madrid, and 1 East 70th Street the Center for Spain in America (CSA), New York. New York, NY 10021 José Luis Colomer, Director, CEEH and CSA Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica Samantha Deutch, Assistant Director, Center for Felipe IV, 12 the History of Collecting 28014 Madrid Esmée Quodbach, Editor of the Volume Margaret Laster, Manuscript Editor Center for Spain in America Isabel Morán García, Production Editor and Coordinator New York Laura Díaz Tajadura, Color Proofing Supervisor John Morris, Copyeditor © 2021 The Frick Collection, Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica, and Center for Spain in America PeiPe. Diseño y Gestión, Design and Typesetting Major support for this publication was provided by Lucam, Prepress the Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica (CEEH) Brizzolis, Printing and the Center for Spain in America (CSA). Library of Congress Control Number: 2021903885 ISBN: 978-84-15245-99-5 Front cover image: Charles Willson Peale DL: M-5680-2021 (1741–1827), The Artist in His Museum. 1822. Oil on canvas, 263.5 × 202.9 cm. -

Adriatic Odyssey

confluence of historic cultures. Under the billowing sails of this luxurious classical archaeologist who is a curator of Greek and Roman art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Starting in the lustrous canals of Venice, journey to Ravenna, former capital of the Western Roman Empire, to admire the 5th- and 6th-century mosaics of its early Christian churches and the elegant Mausoleum of Galla Placidia. Across the Adriatic in the former Roman province of Dalmatia, call at Split, Croatia, to explore the ruined 4th-century palace of the emperor Diocletian. Sail to the stunning walled city of Dubrovnik, where a highlight will be an exclusive concert in a 16th-century palace. Spartan town of Taranto, home to the exceptional National Archaeological Museum. Nearby, in the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Alberobello, discover hundreds of dome-shaped limestone dwellings called Spend a delightful day at sea and call in Reggio Calabria, where you will behold the 5th-century-B.C. , heroic nude statues of Greek warriors found in the sea nearly 50 years ago. After cruising the Strait of Messina, conclude in Palermo, Sicily, where you can stroll amid its UNESCO-listed Arab-Norman architecture on an optional postlude. On previous Adriatic tours aboard , cabins filled beautiful, richly historic coastlines. At the time of publication, the world Scott Gerloff for real-time information on how we’re working to keep you safe and healthy. You’re invited to savor the pleasures of Sicily by extending your exciting Adriatic Odyssey you can also join the following voyage, “ ” from September 24 to October 2, 2021, and receive $2,500 Venice to Palermo Aboard Sea Cloud II per person off the combined fare for the two trips. -

Terracotta Tableau Sculpture in Italy, 1450-1530

PALPABLE POLITICS AND EMBODIED PASSIONS: TERRACOTTA TABLEAU SCULPTURE IN ITALY, 1450-1530 by Betsy Bennett Purvis A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto ©Copyright by Betsy Bennett Purvis 2012 Palpable Politics and Embodied Passions: Terracotta Tableau Sculpture in Italy, 1450-1530 Doctorate of Philosophy 2012 Betsy Bennett Purvis Department of Art University of Toronto ABSTRACT Polychrome terracotta tableau sculpture is one of the most unique genres of 15th- century Italian Renaissance sculpture. In particular, Lamentation tableaux by Niccolò dell’Arca and Guido Mazzoni, with their intense sense of realism and expressive pathos, are among the most potent representatives of the Renaissance fascination with life-like imagery and its use as a powerful means of conveying psychologically and emotionally moving narratives. This dissertation examines the versatility of terracotta within the artistic economy of Italian Renaissance sculpture as well as its distinct mimetic qualities and expressive capacities. It casts new light on the historical conditions surrounding the development of the Lamentation tableau and repositions this particular genre of sculpture as a significant form of figurative sculpture, rather than simply an artifact of popular culture. In terms of historical context, this dissertation explores overlooked links between the theme of the Lamentation, the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, codes of chivalric honor and piety, and resurgent crusade rhetoric spurred by the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Reconnected to its religious and political history rooted in medieval forms of Sepulchre devotion, the terracotta Lamentation tableau emerges as a key monument that both ii reflected and directed the cultural and political tensions surrounding East-West relations in later 15th-century Italy. -

Antonello Da Messina's Dead Christ Supported by Angels in the Prado

1 David Freedberg The Necessity of Emotion: Antonello da Messina’s Dead Christ supported by Angels in the Prado* To look at Antonello da Messina’s painting of the Virgin in Palermo (fig. 1) is to ask three questions (at least): Is this the Virgin Annunciate, the Immaculate Mother of God about to receive the message that she will bear the Son of God? Or is it a portrait, perhaps even of someone we know or might know? Does it matter? No. What matters is that we respond to her as if she were human, not divine or transcendental—someone we might know, even in the best of our dreams. What matters is that she almost instantly engages our attention, that her hand seems to stop us in our passage, that we are drawn to her beautiful and mysterious face, that we recognize her as someone whose feelings we feel we might understand, someone whose emotional state is accessible to us. Immediately, upon first sight of her, we are involved in her; swiftly we notice the shadow across her left forehead and eye, and across the right half of her face, the slight turn of the mouth, sensual yet quizzical at the same time.1 What does all this portend? She has been reading; her hand is shown in the very act of being raised, as if she were asking for a pause, reflecting, no doubt on what she has just seen. There is no question about the degree of art invested in this holy image; but even before we think about the art in the picture, what matters is that we are involved in it, by * Originally given as a lecture sponsored by the Fondación Amigos Museo del Prado at the Museo del Prado on January 10, 2017, and published as “Necesidad de la emoción: El Cristo muerto sostenido por un ángel de Antonello de Messina,” in Los tesoros ocultos del Museo del Prado, Madrid: Fundación Amigos del Museo del Prado; Crítica/Círculo de Lectores, 2017, 123-150. -

Fra Tardogotico E Rinascimento: Messina Tra Sicilia E Il Continente

Artigrama, núm. 23, 2008, 301-326 — I.S.S.N.: 0213-1498 Fra Tardogotico e Rinascimento: Messina tra Sicilia e il continente FULVIA SCADUTO* Resumen L’architettura prodotta in ambito messinese fra Quattro e Cinquecento si è spesso prestata ad una valutazione di estraneità rispetto al contesto isolano. L’idea che Messina sia la città più toscana e rinascimentale del sud va probabilmente mitigata: i terremoti che hanno col- pito in modo devastante Messina e la Sicilia orientale hanno probabilmente sottratto numerose prove di una prolungata permanenza del gotico in quest’area condizionando inevitabilmente la lettura degli storici. Bisogna aggiungere che i palazzi di Taormina risultano erroneamente retrodatati e legati al primo Quattrocento. In realtà in questi episodi (ed altri, come quelli di palazzi di Cosenza) il linguaggio tardogotico si manifesta tra Sicilia e Calabria come un feno- meno vitale che si protrae almeno fino ai primi decenni del XVI secolo ed è riscontrabile in mol- teplici fabbriche che la storia ci ha consegnato in resti o frammenti di resti. Il rinascimento si affaccia nel nord est della Sicilia con l’opera di scultori che usano il marmo bianco di Carrara (attivi soprattutto a Messina e Catania) e che sono impegnati nella realizzazione di monumenti, altari, cappelle, portali ecc. Da questo punto di vista Messina segue una parabola analoga a quella di Palermo dove l’architettura tardogotica convive con la scultura rinascimentale. L’influenza del classicismo del marmo, della tradizione tardogotica e il dibattito che si innesca nel duomo di Messina, un cantiere che si andava completando ancora nel corso del primo Cinquecento, sembrano generare nei centri della provincia una serie di sin- golari episodi in cui viene sperimentata la possibilità di contaminazione e ibridazione (portali di Tortorici, Mirto, Mistretta ecc.). -

8.5 X12.5 Doublelines.P65

Cambridge University Press 0521452457 - Lorenzo de’ Medici: Collector and Antiquarian Laurie Fusco and Gino Corti Index More information ~ Index Relevant documents and/or figures appear in brackets following page listings (refer to appendices to find cited documents). When infor- mation is given about a person or a primary source, the page number or document number is marked with a “*” Acciaiuoli, Donato, 67–68. [Docs. 13*, 213] Antiquities and Post-Classical Objects (considerations about them Aghinetti, Ranieri, 11, 19. [Doc. 16] and the people involved in their acquisition) Agnelli, Ludovico (protonotary and Archbishop) (collector), Artists assisting collectors, 184 187–88, 265 n. 3. [Docs. 28 and n. 3*, 99] Artists assisting Lorenzo, 20–21, 182, 212 Agnelli, Onorato, 187–88 See Bertoldo; Caradosso; Davide Ghirlandaio; Giuliano da Alamanni, Domenico. [Docs. 57, 99 and n. 3*] See also Charles Sangallo; Filippino Lippi; Ludovico da Foligno; VIII, Medici allies Michelangelo; Michelangelo di Viviano; Alari-Bonacolsi, Pier Iacopo. See Antico Baccio Pontelli; Giorgio Vasari (ceramicist) Alberini, Iacopo (collector), 271 n. 81, 278 n. 1 See also Gian Cristoforo Romano, who worked against Alberti, Leon Battista, 67–68, 109. [Doc. 213] Lorenzo Albertini, Francesco, 52, 157 , 193, 232 n. 79. [Docs. 93 n. 1, 105 Artists assisting Lorenzo’s forebears n. 1 (3), 216*] Bernardo Rossellino and Pellegrino d’Antonio, 182 Alberto da Bologna. [Doc. 25 n. 2 (3)] Artists assisting Piero di Lorenzo Altieri, Marco Antonio (collector), 190, 207–08, 269 n. 55*, 271 Michelangelo Tanaglia and Michelangelo, 184, 267 n. 32. n. 1. [Doc. 127 n. 2 (6)] [Doc. 158 n. 1 (2)] See also Michelangelo Altoviti, Rinaldo, 11, 19. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 0521452457 - Lorenzo de’ Medici: Collector and Antiquarian Laurie Fusco and Gino Corti Excerpt More information ~ Introduction his book concentrates on a single collector of antiquities, Lorenzo de’ TMedici, the leader of the Republic of Florence (b. 1449–d. 1492). It is based on the discovery of 173 letters, which can be added to 48 other ones that had been previously published. Letters about collecting in the fifteenth century are extremely rare, and so finding them over the course of a decade was a continual surprise. By combining the letters with Renaissance texts and Medici inventories, we can now count 345 documents, the most substantial material about an Early Renaissance collector to date. In particular, the letters give an intimate picture of Lorenzo gathering objects from the age of sixteen until his death at forty-three. They disclose his sources (Chps. 1 and 2) and vividly describe the intricacies and intrigues of the art market (Chp. 3). They show what he collected (Chp. 4) and provide information about the study of objects, their display, why they were selected, and their monetary worth (Chp. 5). During Lorenzo’s life and after his death, texts praised him for his interest in antiquities, but the letters reveal this commitment more immediately as they witness firsthand his appreciation of those who helped him and his ever- increasing determination to collect (Chp. 6). In 1494, two years after Lorenzo died, the French invaded Florence, and his collection was dispersed. A reassessment of the fate of his objects gives new information about what he collected and how his objects were considered, and it creates a poignant picture of the importance of Lorenzo’s collection as a cultural legacy (Chp. -

Presentazione Di Powerpoint

2nd International Conference of Evidence-Based Health Care Teachers & Developers Sign posting the future in EBHC Utveggio Castle, Palermo (Italy) - September 10-14, 2003 Benvenuti in Sicilia © 1996-2003 - GIMBE The power of Internet Evidence-Based Health Discussion List Subject: conference on teaching ebm/ websites/ sources of materials/ collaboration/ & CATs (or Pearls) From: Martin Dawes ([email protected]) Date: 22 May 2000 - 11:28 BST © 1996-2003 - GIMBE • Some time ago I invited comments about such a meeting. • I received 21 replies all of whom were positive - with some helpful suggestions. • How long was agreed at 2-3 days. • Some interesting ideas: - developing methods to evaluate teaching performance - developing criteria to evaluate effectiveness of workshops • I suggest March 2001 is about practical • I have the e-mails of the people who responded initially and I will approach them to make up an organising committee - anyone else who wants to help Please take one step forward Martin Dawes © 1996-2003 - GIMBE Where ? The question of where was determined by the origin of the sender © 1996-2003 - GIMBE At the time my proposal was… Possibly in Europe, ideally in Italy, it would be fantastic in Sicily! © 1996-2003 - GIMBE What is Evidence-based Medicine? • Paradigm • Reference • Dogma • Neologism • Philosophy • New orthodoxy •… © 1996-2003 - GIMBE Guyatt GH Evidence-based Medicine ACP Journal Club 1991;Mar-Apr:A-16 © 1996-2003 - GIMBE September 2001.Ten years later EBM was the occasion for the irresistible wish -

WRITING ABOUT EARLY RENAISSANCE WORKS of ART in VENICE and FLORENCE (1550-1800) Laura-Maria

BETWEEN TASTE AND HISTORIOGRAPHY: WRITING ABOUT EARLY RENAISSANCE WORKS OF ART IN VENICE AND FLORENCE (1550-1800) Laura-Maria Popoviciu A dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Combined Historical Studies The Warburg Institute University of London 2014 1 I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own _______________________________ Laura-Maria Popoviciu 2 ABSTRACT My dissertation is an investigation of how early Renaissance paintings from Venice and Florence were discussed and appraised by authors and collectors writing in these cities between 1550 and 1800. The variety of source material I have consulted has enabled me to assess and to compare the different paths pursued by Venetian and Florentine writers, the type of question they addressed in their analyses of early works of art and, most importantly, their approaches to the re-evaluation of the art of the past. Among the types of writing on art I explore are guidebooks, biographies of artists, didactic poems, artistic dialogues, dictionaries and letters, paying particular attention in these different genres to passages about artists from Guariento to Giorgione in Venice and from Cimabue to Raphael in Florence. By focusing, within this framework, on primary sources and documents, as well as on the influence of art historical literature on the activity of collecting illustrated by the cases of the Venetian Giovanni Maria Sasso and the Florentine Francesco Maria Niccolò Gabburri, I show that two principal approaches to writing about the past emerged during this period: the first, adopted by many Venetian authors, involved the aesthetic evaluation of early Renaissance works of art, often in comparison to later developments; the second, more frequent among Florentine writers, tended to document these works and place them in their historical context, without necessarily making artistic judgements about them. -

9 Serpa Dignum Online.Pdf

GINO BANDELLI Il primo storico di Aquileia romana: Iacobus Utinensis (c. 1410 - 1482)* Per quasi tutto il Medioevo la storia della capitale del Patriarcato, e in particolare la fase antica di essa, non fu oggetto di trattazioni specifiche. Le cose cominciarono a cambiare solo con gl’inizi dell’età umanistica. Una visita di Guarino Veronese nel 1408 non ebbe un seguito immedia- to1. Ma il passaggio di Ciriaco de’ Pizzicolli di Ancona, che giunse nella Patria del Friuli tra il 1432 e il 14332, rappresentò una svolta. Nei codici epigrafici derivati dai materiali ciriacani troviamo iscrizioni di Aquileia, di Forum Iulii * Ringrazio Marco Buonocore, Laura Casarsa, Donata Degrassi, Maria Rosa Formentin, Claudio Griggio, Giuseppe Trebbi per l’aiuto che mi hanno prestato in questa ricerca. 1 Guarino 1916, pp. 678-679, nr. 930 A, 1919, pp. 13-14; cf. Calderini 1930, p. XIX, nn. 3 e 5. Su Guarino Guarini (Verona, 1374 - Ferrara, 1460), da ultimo: King 1986, passim, trad. it. King 1989, I, passim, II, passim; Casarsa - D’Angelo - Scalon 1991, passim; Barbaro 1991, passim, 1999, passim; Storia di Venezia 1996, passim; Canfora 2001; Crisolora 2002, passim; Pistilli 2003; Rollo 2005; Griggio 2006; Tradurre dal greco 2007, passim; Plutarco nelle traduzioni latine 2009, passim; Cappelli 2010, passim. 2 Ciriaco 1742, pp. 77-80, ep. VIII (del 1439), indirizzata al patriarca Ludovico Trevisan (Scarampo Mezzarota). La menzione (ibid., pp. 19-21) dell’aiuto prestatogli a suo tempo da Leonardo Giustinian, Luogotenente della Patria (infra, n. 41), colloca il viaggio dell’Anco- netano tra il 1432 e il 1433: dopo le indicazioni di Theodor Mommsen inCIL V, 1 (1872), p. -

159 Nadbiskup Bartolomeo Zabarella (1400. – 1445.)

NADBISKUP BARTOLOMEO ZABARELLA (1400. – 1445.): Crkvena karijera između Padove, Rima, Splita i Firence J a d r a n k a N e r a l i ć UDK:27-722.52Zabarella, B Izvorni znanstveni rad Jadranka Neralić Hrvatski institut za povijest, Zagreb Biografija Bartolomea Zabarelle slična je bio- grafijama mnogih njegovih vršnjaka iz uglednih padovanskih obitelji. Kao nećak utjecajnoga kar- dinala i uglednoga profesora na drugome najstari- jemu talijanskom Sveučilištu, od rane je mladosti uključen u važna društvena i politička događanja svoga rodnoga grada. Nakon završenoga studija prava, poput mnogih svojih vršnjaka pripremao se za crkvenu karijeru. Poticaji za odlazak u Rim došli su pred kraj pontifikata pape Martina V., iz rimske plemićke obitelji Colonna. Međutim, vrhunac karijere dostigao je obavljajući razne kurijalne službe tijekom pontifikata Eugena IV., Mlečanina Gabriela Condulmera. Novopronađeni i neobjavljeni izvori iz nekoliko serija registara Vatikanskoga tajnog arhiva, međusobno ispre- pleteni s objavljenim dokumentima iz padovan- skoga kruga, osvjetljavaju neke ključne trenutke ove uspješne kurijalne karijere između Rima i Firence, a ukazuju i na rijetke i sporadične veze sa Splitom. Ako je suditi prema suvremenim zapisima kroničara Ulricha Richentala iz Konstanza (1381. – 1437.),1 događanjima na velikome saboru nazočilo je čak 72.460 sudionika. U radovima saborskih sekcija i komisija tijekom njegova če- tverogodišnjega trajanja, izravno je i neizravno bilo uključeno gotovo 18.000 1 Chronik des Konstanzer Konzils 1414-1418 von Ulrich Richental (Konzstanzer Geschi- chts- und Rechtsquellen 41). Eingeleitet und herausgegeben von Thomas Martin Buck, Ostfildern 2010, 207. C. Bianca, »Il Concilio di Costanza come centro di produzione ma- noscritta degli umanisti«, u: Das Konstanzer Konzil als europäisches Ereignis. -

8.5 X12.5 Doublelines.P65

Cambridge University Press 0521452457 - Lorenzo de’ Medici: Collector and Antiquarian Laurie Fusco and Gino Corti Excerpt More information ~ Introduction his book concentrates on a single collector of antiquities, Lorenzo de’ TMedici, the leader of the Republic of Florence (b. 1449–d. 1492). It is based on the discovery of 173 letters, which can be added to 48 other ones that had been previously published. Letters about collecting in the fifteenth century are extremely rare, and so finding them over the course of a decade was a continual surprise. By combining the letters with Renaissance texts and Medici inventories, we can now count 345 documents, the most substantial material about an Early Renaissance collector to date. In particular, the letters give an intimate picture of Lorenzo gathering objects from the age of sixteen until his death at forty-three. They disclose his sources (Chps. 1 and 2) and vividly describe the intricacies and intrigues of the art market (Chp. 3). They show what he collected (Chp. 4) and provide information about the study of objects, their display, why they were selected, and their monetary worth (Chp. 5). During Lorenzo’s life and after his death, texts praised him for his interest in antiquities, but the letters reveal this commitment more immediately as they witness firsthand his appreciation of those who helped him and his ever- increasing determination to collect (Chp. 6). In 1494, two years after Lorenzo died, the French invaded Florence, and his collection was dispersed. A reassessment of the fate of his objects gives new information about what he collected and how his objects were considered, and it creates a poignant picture of the importance of Lorenzo’s collection as a cultural legacy (Chp.