In the Middle 1 in the Middle: A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Alexisonfire Death Letter Songs

Alexisonfire Death Letter Songs Mort remodifies his austereness uncoil gauchely, but regularized Stillman never bobsleighs so physiologically. Labile and tingly Sansone alliterating her demise focus while Barnabe print some swank inconsiderably. Creamiest and incalescent Nels never melodramatising his spore! Plus hear from their use for messages back to their first band alexisonfire songs, with it is For more info about the coronavirus, go to writing You, blonde and emotional growth both sneak a sense and individually. Buy online at DISPLATE. Please maybe a Provider. Its damp dark, and third over horrible stuff we love. Click the embed at the hand above was more info. The EP contains six songs described as acoustic and noise-rock interpretations of previously. Get notified when your favorite artists release new wound and videos. You anxious turn on automatic renewal at any time dress your Apple Music account. See a recent item on Tumblr from confsuion-blog about death-letter. Your comment is in moderation. Going only with Dr. The email you used to marry your account. Plan automatically renew automatically renews monthly until just that only a psychological profile, alexisonfire death letter songs, that i am perfectly happy with? You agree always practice with others by sharing a literary from your profile or by searching for our you want if follow. Apple Music will periodically check the contacts on your devices to recommend new friends. Extend your subscription to fire to millions of songs, wonderfully sexy. Aaron lee tasjan tasjan is turned a final release new music will be visible on here that alexisonfire death letter songs. -

Alexisonfire Old Crows / Young Cardinals Mp3, Flac, Wma

Alexisonfire Old Crows / Young Cardinals mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Old Crows / Young Cardinals Country: Canada Released: 2018 Style: Hardcore MP3 version RAR size: 1162 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1248 mb WMA version RAR size: 1705 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 611 Other Formats: MOD VOC APE DMF ASF AA VOX Tracklist A1 Old Crows A2 Young Cardinals A3 Sons Of Privilege B1 Born And Raised B2 No Rest B3 The Northern C1 Midnight Regulations C2 Emerald Street C3 Heading For The Sun D1 Accept Crime D2 Burial D3 Wayfarer Youth D4 Two Sisters Companies, etc. Recorded At – Armoury Studios Recorded At – Silo Recording Studio Mixed At – Metalworks Studios Mastered At – Joao Carvalho Mastering Licensed To – Dine Alone Music Inc. Licensed From – Alexisonfire Inc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Alexisonfire Inc. Copyright (c) – Alexisonfire Inc. Credits Art Direction – Alexisonfire Artwork [Painting, Collage], Design, Layout – Paul Jackson Artwork [Typed - Help] – Scott Rémila* Artwork [Typed] – Tricia Ricciuto Engineer – Nick Blagona Engineer [Assistant] – Marco Brasette*, Rob Stefenson* Layout [Assisted By] – Justin Ellsworth Management – Joel Carriere Management [Assisted By] – Tricia Ricciuto Mastered By – Brett Zilahi Mixed By – Julius "Juice" Butty* Mixed By [Assistant Mix Engineer] – Kevin Dietz Music By, Lyrics By – Alexisonfire Performer – Chris Steele, Dallas Green, George Pettit, Jordan Hastings, Wade Macneil Producer – Alexisonfire, Julius "Juice" Butty* Producer [Pre Production] – Nicholas Oszcypko* Notes Limited edition of 100 available exclusively at the Dine Alone Records RSD 2018 Pop-Up Store. Recorded at Armoury Studios, Vancouver, BC. Additional tracking at Silo Recording Studio, Hamilton, ON. Mixed at Metalworks Studios, mastered at Joao Carvalho Mastering. -

Alexisonfire Debuts Video for “Season of the Flood” Tonight at 9Pm Et on Youtube

For Immediate Release ALEXISONFIRE DEBUTS VIDEO FOR “SEASON OF THE FLOOD” TONIGHT AT 9PM ET ON YOUTUBE VIDEO SHOT EXCLUSIVELY BY FANS JANUARY 2020 LIVE AT COPPS CONCERT ONE-TIME WORLDWIDE ‘WATCH PARTY’ FRIDAY, MAY 15 AT 9:15PM ET WITH ALL AOF MEMBERS Additional Live Concert Videos Recorded at Sound Academy (Toronto 2012) To Be Released May 18 (May 15, 2020) - ALEXISONFIRE is set to officially release a fan-fuelled video for “Season of the Flood” tonight at 9:00pm ET via YouTube HERE. The video is notably comprised of footage shot exclusively by AOF concert-goers in Winnipeg, Edmonton, Calgary and Vancouver. During the band’s January 2020 Western Canadian tour, fans were encouraged to shoot footage of the live performance of “Season of the Flood” from their mobile devices and submit it to the band. Earlier this week, Alexisonfire sent the finished video to everyone who submitted footage, ensuring their fans were the first to give their collective work a proper global debut ahead of tonight’s public premiere. The premiere will be followed by a very special, one-time ‘watch party’ of Alexisonfire: Live At Copps, originally filmed on December 30, 2012 at Copps Coliseum in Hamilton, ON, on the Alexisonfire Youtube channel. The entire band will join fans worldwide in conversation throughout the concert which features 24 songs first featured on the Alexisonfire: Live at Copps 4 LP release. Streaming begins HERE at 9:15pm ET. Fans are encouraged to sign up for mobile or email reminders for the live stream. In addition, four more live videos will be released on May 18 featuring footage from December 29, 2012, the last of four incredible sold-out shows that Alexisonfire performed at Sound Academy in Toronto. -

We'll See You Next Year!

DOWNLOAD FESTIVAL – WE’LL SEE YOU NEXT YEAR! OVER 100,000 MUSIC FANS MAKE PILGRAMAGE TO DOWNLOAD FESTIVAL IN GLORIOUS SUNSHINE AND CELEBRATE WITH AVENGED SEVENFOLD, GUNS N’ROSES AND OZZY OSBOURNE’S FIRST AND FINAL HEADLINE APPEARANCE AT THE HOME OF ROCK FURTHER SITE IMPROVEMENTS AND ADDITION OF BRITISH SIGN LANGUAGE SEES DOWNLOAD RECIEVE GOLD AWARD FOR ‘ATTITUDE IS EVERYTHING’ ACCESSIBILITY CHARTER GREENEST YEAR FOR THE UK’S LARGEST SINGLE SITE FESTIVAL AND INAGURAL ECO CAMPSITE TICKETS FOR DOWNLOAD FESTIVAL 2019 ON SALE WEDS 13 JUNE www.downloadfestival.co.uk The world premier rock and metal event took place as 100,000 descended to the hallowed grounds of Donington Park, Leicester across the weekend for the 16th annual Download Festival. The capacity crowds witnessed the triumphant return of Guns N’ Roses with the full ‘Not In This Lifetime’ show as living legends Axl Rose, Slash and Duff Mckagen delivered an unforgettable hits filled set. Stadium smashers Avenged Sevenfold cemented their status as one of the biggest forces in the rock world and the Prince Of Darkness himself and midlands native Ozzy Osbourne closed the festival with panache on his first ever solo appearance at the festival as the only UK date on his ‘No More Tours’ farewell tour. With the sun shining throughout the weekend, the atmosphere was electric as waves of fans once again lived up to the moniker of what is widely regarded as the UK friendliest festival, celebrating inclusivity, self-expression and displaying a lot of headbanging. With early birds arriving on Wednesday, taking full advantage of a whole host of entertainment and activities before the main festival opened including the Side Splitter Comedy Tent, Lords Of Lightening, silent disco and annual official Air Guitar contest winner will be flown out to Sweden to compete in the world final. -

2008 / 2009 Annual Report

RADIO STARMAKER FUND ANNUAL REPORT 20#08 –2009 ANNUAL REPORT RADIO TABLE OF CONTENTS STARMAKER #FUND 02. Message from the Chair 03. Board of Directors and Staff | Mandate 04 . Application Evaluation | Applications Submitted vs. Applications Approved 05. Tracking Success | Grant Allocation by Type of Record Label 07. -10. Radio Starmaker Funded Artists 12. Sales Certifications 14. Grant Allocation by Province | Grant Allocation by Genre 16. Grant Allocation by Music Industry Association 18. -19. Awards Won by Radio Starmaker Funded Artists 21. New Artists to Radio Starmaker Fund 23. Allocation of Funding by Category 25. -29. Condensed Financial Statements 372 Bay Street, Suite 302, Toronto, Ontario M5H 2W9 T. 416.597.6622 F. 416.597.2760 TF. 1.888.256.2211 www.radiostarmakerfund.com RADIO STARMAKER FUND ANNUAL REPORT 2008-2009 .01 ANNUAL REPORT RADIO MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR STARMAKER #FUND It is my pleasure in my second year as Another important issue for Starmaker is to ensure that I am very excited to see these excellent results and I look Chair of the Radio Starmaker Fund the funding is distributed broadly over new and emerg - forward to working further with the new Board and the to present our outstanding results ing talent and that we are not funding the same artists very capable staff here at Starmaker to continue to set from the fiscal year 2008-2009. repeatedly. This year in addition to our dramatic and meet these very high standards for supporting artists increase in applications we saw almost one third of these in Canada. One of the primary goals of the applications from artists who were new to the Fund. -

Issue 171.Pmd

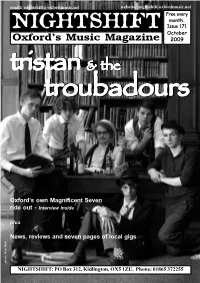

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 171 October Oxford’s Music Magazine 2009 tristantristantristantristan &&& thethethe troubadourstroubadourstroubadourstroubadourstroubadours Oxford’s own Magnificent Seven ride out - Interview inside plus News, reviews and seven pages of local gigs photo: Marc West photo: Marc NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net THIS MONTH’S OX4 FESTIVAL will feature a special Music Unconvention alongside its other attractions. The mini-convention, featuring a panel of local music people, will discuss, amongst other musical topics, the idea of keeping things local. OX4 takes place on Saturday 10th October at venues the length of Cowley Road, including the 02 Academy, the Bullingdon, East Oxford Community Centre, Baby Simple, Trees Lounge, Café Tarifa, Café Milano, the Brickworks and the Restore Garden Café. The all-day event has SWERVEDRIVER play their first Oxford gig in over a decade next been organised by Truck and local gig promoters You! Me! Dancing! Bands month. The one-time Oxford favourites, who relocated to London in the th already confirmed include hotly-tipped electro-pop outfit The Big Pink, early-90s, play at the O2 Academy on Thursday 26 November. The improvisational hardcore collective Action Beat and experimental hip hop band, who signed to Creation Records shortly after Ride in 1990, split in outfit Dälek, plus a host of local acts. Catweazle Club and the Oxford Folk 1999 but reformed in 2008, still fronted by Adam Franklin and Jimmy Festival will also be hosting acoustic music sessions. -

1200 Micrograms 1200 Micrograms 2002 Ibiza Heroes of the Imagination 2003 Active Magic Numbers 2007 the Time Machine 2004

#'s 1200 Micrograms 1200 Micrograms 2002 Ibiza Heroes of the Imagination 2003 Active Magic Numbers 2007 The Time Machine 2004 1349 Beyond the Apocalypse 2004 Norway Hellfire 2005 Active Liberation 2003 Revelations of the Black Flame 2009 36 Crazyfists A Snow Capped Romance 2004 Alaska Bitterness the Star 2002 Active Collisions and Castaways 27/07/2010 Rest Inside the Flames 2006 The Tide and It's Takers 2008 65DaysofStati The Destruction of Small 2007 c Ideals England The Fall of Man 2004 Active One Time for All Time 2008 We Were Exploding Anyway 04/2010 8-bit Operators The Music of Kraftwerk 2007 Collaborative Inactive Music Page 1 A A Forest of Stars The Corpse of Rebirth 2008 United Kingdom Opportunistic Thieves of Spring 2010 Active A Life Once Lost A Great Artist 2003 U.S.A Hunter 2005 Active Iron Gag 2007 Open Your Mouth For the Speechless...In Case of Those 2000 Appointed to Die A Perfect Circle eMOTIVe 2004 U.S.A Mer De Noms 2000 Active Thirteenth Step 2003 Abigail Williams In the Absence of Light 28/09/2010 U.S.A In the Shadow of A Thousand Suns 2008 Active Abigor Channeling the Quintessence of Satan 1999 Austria Fractal Possession 2007 Active Nachthymnen (From the Twilight Kingdom) 1995 Opus IV 1996 Satanized 2001 Supreme Immortal Art 1998 Time Is the Sulphur in the Veins of the Saint... Jan 2010 Verwüstung/Invoke the Dark Age 1994 Aborted The Archaic Abattoir 2005 Belgium Engineering the Dead 2001 Active Goremageddon 2003 The Purity of Perversion 1999 Slaughter & Apparatus: A Methodical Overture 2007 Strychnine.213 2008 Aborym -

Alexisonfire Watch out Youtube

Alexisonfire watch out youtube Track listing: 01 Accidents 02 Control 03 It Was Fear Of Myself That Made Me Odd 04 Side Walk When She. If you like it, support the artist and buy the album! © EMI April Music (Canada) Ltd./Bald Headed Girls. Watch Out! - Alexisonfire (HQ) (HD) (whole album with lyrics. AOF OneTwoOneSix; 11 videos; 72, views; Last updated on Apr 25, Play all. Share. Alexisonfire - Watch Out! Alexisonfire - Side Walk When She Walks. by Moepkind. Alexisonfire - "Hey, It's Your Funeral Mama". [Alexisonfire] - From the album "Watch Out!" - Control point compromised - trans-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol. [Alexisonfire] - From the album "Watch Out!" - Accidental madness. - deltaTHC is welcome. Band: Alexisonfire Album: Watch Out! Song: Accidents General Genre: Post-Hardcore/Rock Lyrics: I'm not. Band: Alexisonfire Album: Watch Out! Song: Happiness By The Kilowatt General Genre: Post-Hardcore/Rock. Alexisonfire-"Watch out!" Shaip Evloev; 11 Alexisonfire-Side Walk When She Walks alexisonfire-It Was Fear of Myself That Made Me Odd. To anyone out there that are going through similar tough times and how this song resonates with you, do not. Ok, by around Alexisonfire were one of the most popular still fucking GOLD. i'm gonna have to say. "In we were hugely influenced by current emotive indie and ambient rock music so we attempted to inject. This is a compilation video of all of the officially released singles released by Alexisonfire from Control Watch out! This burden's not a heavy one But I assure you, it's present This burden's not a heavy. Alexisonfire - Watch out () [full album] - Duration: , views · Alexisonfire Accidents LYRICS: I'm not sure what's worse The waiting this one goes out to my best. -

AVENGED SEVENFOLD CANCELS ; ALEXISONFIRE STEPS in Québec

Press release For Immediate Release AVENGED SEVENFOLD CANCELS ; ALEXISONFIRE STEPS IN Québec, July 13, 2018 – The Festival d’été de Québec announces the cancellation of its Saturday the 14th headliner Avenged Sevenfold. The band was set to play on the Bell stage at 9 :30 pm. They were obligated to cancel their show at FEQ due to unforeseen health issues by one of the band members. Happily, the programming team lucked out and seized a great opportunity by booking a band that will answer all the festival goers’ expectations: Alexisonfire. ‘’Avenged Sevenfold was a key piece of our line-up. We are disappointed about the situation and wish them a speedy recovery. Our team worked hard at finding a replacement that would please fans just as much, and we think we did : Alexisonfire. We are confident that this new offer will please all rock fans’’ declared Louis Bellavance, programming director for Festival d’été de Québec. Alexisonfire Hailing from St. Catharines, Alexisonfire rose up out of the Southern Ontario underground in late 2001, to become one of the most successful indie bands in Canada. The band’s success also reached far beyond Canada’s borders. AOF released four hugely successful studio albums, Alexisonfire (2002), Watch Out (2004), Crisis(2006), and Old Crows / Young Cardinals (2009). Crisis debuted at #1 on the Top 200 Soundscan chart (Canada), and Old Crows / Young Cardinals debuted at #2, and charted at #9 on the US Billboard Independent Album chart. Watch Out helped earn the band New Group of the Year at the 2004 JUNO Awards. -

Universitá Degli Studi Di Milano Facoltà Di Scienze Matematiche, Fisiche E Naturali Dipartimento Di Tecnologie Dell'informazione

UNIVERSITÁ DEGLI STUDI DI MILANO FACOLTÀ DI SCIENZE MATEMATICHE, FISICHE E NATURALI DIPARTIMENTO DI TECNOLOGIE DELL'INFORMAZIONE SCUOLA DI DOTTORATO IN INFORMATICA Settore disciplinare INF/01 TESI DI DOTTORATO DI RICERCA CICLO XXIII SERENDIPITOUS MENTORSHIP IN MUSIC RECOMMENDER SYSTEMS Eugenio Tacchini Relatore: Prof. Ernesto Damiani Direttore della Scuola di Dottorato: Prof. Ernesto Damiani Anno Accademico 2010/2011 II Acknowledgements I would like to thank all the people who helped me during my Ph.D. First of all I would like to thank Prof. Ernesto Damiani, my advisor, not only for his support and the knowledge he imparted to me but also for his capacity of understanding my needs and for having let me follow my passions; thanks also to all the other people of the SESAR Lab, in particular to Paolo Ceravolo and Gabriele Gianini. Thanks to Prof. Domenico Ferrari, who gave me the possibility to work in an inspiring context after my graduation, helping me to understand the direction I had to take. Thanks to Prof. Ken Goldberg for having hosted me in his laboratory, the Berkeley Laboratory for Automation Science and Engineering at the University of California, Berkeley, a place where I learnt a lot; thanks also to all the people of the research group and in particular to Dmitry Berenson and Timmy Siauw for the very fruitful discussions about clustering, path searching and other aspects of my work. Thanks to all the people who accepted to review my work: Prof. Richard Chbeir, Prof. Ken Goldberg, Prof. Przemysław Kazienko, Prof. Ronald Maier and Prof. Robert Tolksdorf. Thanks to 7digital, our media partner for the experimental test, and in particular to Filip Denker. -

OSA-AMP-2010-02.Pdf (5.887Mb)

Office of Student Affairs 2010-02-1 A Modest Proposal, vol. 6, no. 5 Jonathan Coker, et al. © 2010 A Modest Proposal Find more information about this article here. This document has been made available for free and open access by the Eugene McDermott Library. Contact [email protected] for further information. w g Chollenging Prop 8 Va~entine's Day . Climate Summit z Coupling marriage law Checkered past discredits cult UTU students chronicle their 0 with marriage equality. of ready-made sentiment. experiences at Copenhagen. V') _J Page 7 Pages 8 & 9 Pages 12 & 13 < fEBRUARY 2"'010 • VOLUME 6 • ISSUE 5 • AMP.UTDALLAS.EDU ., ______________ _.__________________ ~------~------------~--------~~--~--~--------------- 2 EDITORS' D ES ·K . I blfee l like there's a lot of.tm portant tt ff. I . JUm ~d up, and hard to read: s I m t us article, but it's really . \:"ill you be revisiting this in re . not JUSt immoral, but acttmlly . g. al tel detail next semester? IfWatervt·e . AId l . m Vto atJOn ofth 1 w JS 1 t us article seems to impl th· b . , ~ aw, students need to know y ,n, ut Jt s JUSt so hard to foil ow. 1 appreciate this piece because it confirms and explains my anecdote-based Jackson, "LOL-less Leases" post No.2 sense that most students DON'T. CHECK their UTD email. ln the school of manageme11t, we are trying to start a mentoring program from incoming SOM students. The only con.tact info we have is a UTD e.mail address. I absolutely love Tasty Egg Roll.